Ernest Hemingway's Unbelievable Real-Life Story

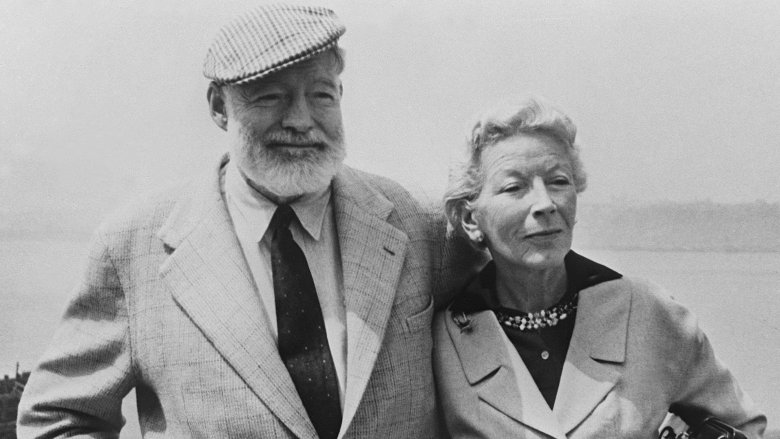

Though Ernest Hemingway was an immensely talented author, he was also an icon of 20th-century bullishness and masculinity, a surprisingly sensitive (if tempestuous) soul, and one of the most beautiful, awful, and intriguing figures in literary history.

In life, he was a reporter, a soldier, and quite a drinker, who would have loved admiration like this even if he despised the bombastic, flowery language we're using. Hemingway's life wasn't the longest, but it was filled with drama, driven by ambition, and streaked with blood. Few can write quite like he could. And few have managed to live like he did, either.

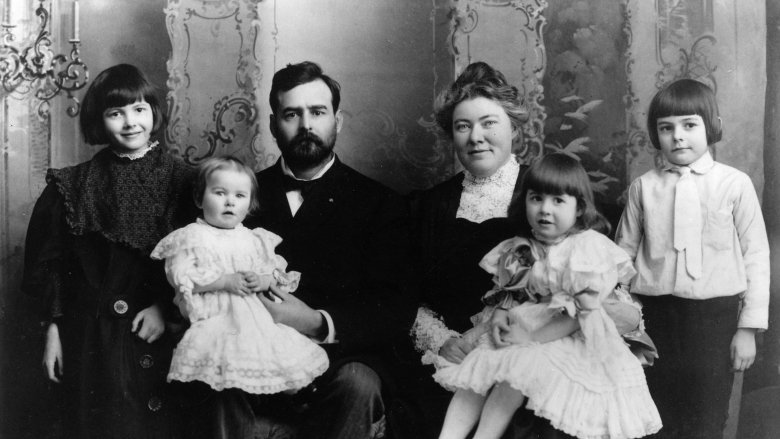

Forced into becoming a twin

Hemingway's childhood wasn't a particularly easy one. He hated his mother — whom he described as an "all-time, all-American b*tch" — and hated his name, which reminded him of Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest. Most peculiar of all was a rather disturbing aspect of his early days which was revealed by his sister in a tell-all biography.

According to her, Hemingway's mother, Grace, was gripped by a desperation to have twin children. In order to feed her fantasies, she dressed the young Ernest up in his older sister's old clothes, including lacy white dresses and pink bows. Eventually, she began buying two of each item of clothing and would dress both children in identical clothes, referring to them as her "sweet Dutch dollies."

Just why little Ernestine — as his mother often referred to him — became so obsessed with masculinity is surely no surprise.

Earning his style

As a young man, Hemingway became a reporter for the Kansas City Star. It was at the Star, where he wrote about police incidents and emergency room happenings, that he was given a copy of the newspaper's style guide. This style guide implored writers to "use short sentences," "use short first paragraphs," and "use vigorous English." Hemingway would later remark that these words were "the best rules I ever learned in the business of writing."

If you've read a single word of Hemingway's, you'll know that he took this advice to heart and never let it go. He's one of the crispest, bluntest writers in modern literature, and to say he uses vigorous English is something of an understatement. That something so recognizable as Hemingway's style could stem from something as innocuous as a style guide is nothing short of extraordinary.

Wounded at war

The breaking out of hostilities in Europe in 1914 marked the beginning of Hemingway's first war. After volunteering in France for the Red Cross, he became an ambulance driver for the American forces after their entry into the war in 1917. Hemingway's most famous days during World War I took place in Italy, where, according to History's biography of his life, he was present at a string of victories along the Piave delta in 1918.

In July 1918, Hemingway was struck by shrapnel from an Austrian mortar shell while visiting Italian soldiers in a dugout. He was wounded in the foot, knee, thighs, scalp, and hand, and was awarded the Croce de Guerra for his service. His experience in Italy would lay the foundations of the plot for A Farewell to Arms, arguably one of his best works.

Hemingway returned from war with the intention of marrying a nurse with whom he'd fallen in love with named Agnes von Kurowsky. Unfortunately, by this time, Kurowsky had already married an Italian officer. Hemingway was left alone.

Meeting the (first) love of his life

In October 1920, Hemingway met Hadley Richardson at a party in Chicago. She was seven years his senior, had a fragile mental state, and was considered a spinster by society's standards. The two fell in love almost immediately. According to the Chicago Tribune's account of her life, Hemingway helped Richardson find a sense of self and overcome some of her traumatic experiences, while Richardson helped Hemingway focus on and refine his own artistic identity and talent.

Hemingway and Hadley married in 1921 and moved to Paris shortly after. Despite enduring a string of suicidal thoughts and a growing obsession with work and alcohol, Hemingway would later idealize his marriage to Hadley, and his time spent in the French capital, as the greatest time of his life.

A star of Paris' golden age

It is difficult to imagine Hemingway without seeing Paris. He is one of that elite cadre of writers, artists, musicians, and thinkers who are intrinsically connected with the city's golden age, a period masterfully retold in Hemingway's final book, A Moveable Feast.

When they arrived, Hemingway and Hadley lived in a sparse apartment with no running water and a bucket for a bathroom. The newlywed Hemingways soon befriended other local personalities, such as Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Picasso, and James Joyce. After a sojourn to Toronto to deliver their first child, the couple returned to Paris — and Hemingway thrived. It was during this period that he wrote The Sun Also Rises and Men Without Women, and dominated the Parisian cultural scene.

In 1927, Hemingway's marriage came to an end when Hadley discovered his affair with a fashion reporter named Pauline Pfeiffer. They divorced, and Hemingway married Pfeiffer later that year. In 1928, Ernest and Pauline Hemingway moved to Key West, Florida.

Papa Hemingway and the mutant cats

The Hemingway Home is one of Florida's most well-known sights and tourist destinations. According to the home's website, Pauline and Hemingway took up residence in an apartment over a car showroom on Simonton Street at the pleasure of Ford Motors, where Hemingway would go on to finish A Farewell to Arms. After a few seasons, Pauline's Uncle Gus purchased a house for them on Whitehead Street, in 1931.

The extraordinarily beautiful house (which was also extraordinarily expensive) is still filled with the Hemingways' own personal touches, including a number of trophy mounts and skins from foreign expeditions, Hemingway's writing studio, and a unique breed of six-toed mutant tomcats who were bred from Hemingway's own.

It was also in Key West that Hemingway received his legendary nickname, "Papa."

Fighting fascism in Spain

In 1937, Hemingway traveled to Spain to report on the Spanish Civil War — a devastating conflict between governmental Republicans and Franco's fascists — for the North American Newspaper Alliance. This wasn't where his contribution to the conflict ended, however. According to The Volunteer, he also paid to send ambulances (and volunteer drivers) to Spain, produced and narrated a pro-Republican documentary, vocally supported the Republican forces in his writing, and, as some theories go, is even thought to have journeyed and fought behind fascist lines.

The war put a strain on Hemingway's marriage with Pauline, however, who, as a devout Catholic, sided with Franco's fascist regime. In Spain, he would meet his next wife — Martha Gellhorn — and take inspiration for arguably his finest work, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Making his mark in Cuba

In 1939, Hemingway moved to the Hotel Ambos Mundos in Havana — a city he had visited and adored years earlier — and began a split with Pauline that was so painful and dramatic that Hemingway made an active attempt to destroy her image and reputation in A Moveable Feast. Soon enough, Hemingway married Martha Gellhorn and the two purchased a home just outside Havana. It would be Hemingway's home for the next 20 years. He spent his time fishing, entertaining guests, and writing. During this period, he and Martha also traveled to China to report on the Sino-Japanese War.

According to Valerie Hemingway, the Ernest's daughter-in-law, his presence is still felt and celebrated in Cuba today, and a case could be made for Cuba being the country most deeply loved by the man himself.

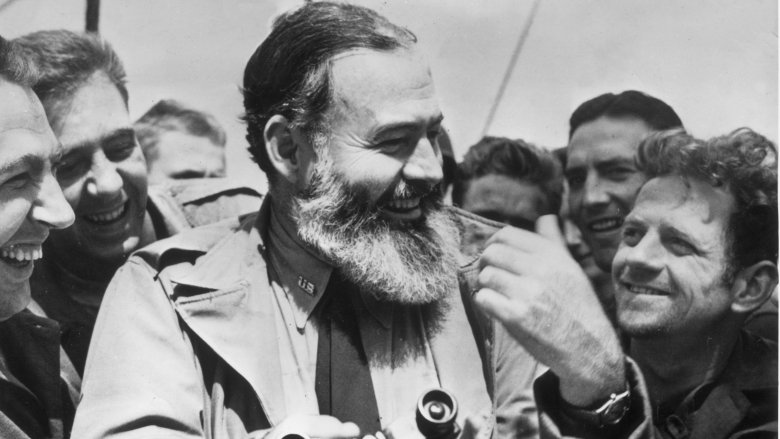

Spymaster, U-boat hunter and hotel liberator

Halfway through the 20th century, Hemingway had one hell of a war. The Warfare History Network posits that it was Hemingway's adventurous spirit that eventually overrode his initial disinterest in the conflict. His first foray into the fight came in the form of an offer to the American ambassador to Cuba to set up a private network of spies to monitor Nazi sympathizers on the island. His team of undercover operatives included waiters, fisherman, prostitutes, aristocrats, and priests.

Apparently encouraged by his own audacity, Hemingway then requested a supply of bazookas, hand grenades, machine guns, and radio equipment from the embassy with the intention of turning his fishing boat into a warship that could hunt German U-boats in the Caribbean. Again, the ambassador agreed. Hemingway and his "Rough Riders" never quite managed to sink a U-boat, however, and Martha Gellhorn considered the enterprise no more than an excuse for Hemingway and his pals to waste fuel and go drinking.

Other adventures for Hemingway during World War II included crashing a car in London, finally ending his deteriorating marriage with Martha after she went ashore on D-Day (while Hemingway was forced to stay aboard a ship), and meeting his next wife, Mary Welsh. He finally topped it all when he "liberated" the bar of the Paris Ritz — days after the Germans had already left — by showing up with a jeep and a machine gun, demanding entry, and racking up a tab for 51 dry Martinis.

The Nobel Prize

After the Second World War, Hemingway returned to Cuba to live with Mary Welsh. In 1954, Hemingway received literature's highest honor: the Nobel Prize. According to The New York Times, he was granted the prize for "his powerful, style-forming mastery of the art of modern narration, as most recently evinced in The Old Man and the Sea."

He beat out Paul Claudel, Albert Camus, and his old friend Ezra Pound to win. Although Hemingway was unable to travel to Stockholm to pick it up because of a series of injuries suffered in a plane crash on a recent trip to Africa, the Nobel Prize marked a further high point in a career that had already reached something of an apex. Six years later, Hemingway and Mary left Cuba.

His last days

The 1960s saw Hemingway endure a steep decline in both his physical and mental health. He had suffered from hepatitis and was largely overweight, and checked in to the Mayo Clinic — ostensibly for hypertension, but actually to receive electroshock therapy — in order to treat his growing paranoia and anxiety. It didn't help. Despite further "treatment" at the clinic, Hemingway's suicidal tendencies worsened considerably, and, on July 2, 1961, Hemingway shot himself with his favorite shotgun.

His death was initially believed to be accidental, as reported in the press at the time, but Mary confirmed five years later that Hemingway had indeed shot himself deliberately. At the time of his death, Hemingway had published seven novels, married four women, fought in three wars, and survived two plane crashes. He was buried in Ketchum, Idaho.