The Scary History Of The Doomsday Clock

It's two minutes to midnight. Even if you haven't ever heard of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and their Doomsday Clock, those words probably make you shiver, just a little bit, because bad things always happen at midnight. And midnight on the Doomsday Clock is the baddest of the bad, the hour of the apocalypse. That's right, the end of the world. Boom. Everyone dies.

Hey, cheer up. When all these facts about the Doomsday Clock have sufficiently freaked you out, you can switch gears and check out the Zombie Doomsday Clock instead. Because that's an apocalypse we can all get behind.

A clock strikes terror

On a beautiful spring day in 1947, a bunch of atomic scientists got together and asked themselves a question: "How can we make everyone in the world simultaneously wet themselves with fear?" It was a profoundly important question with worldwide implications for both humans and for the companies that manufacture adult diapers.

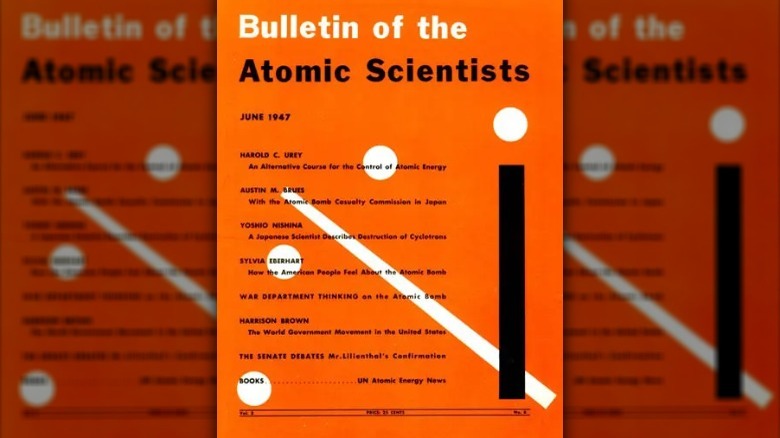

According to Wired, The Doomsday Clock was the brainchild of a group of scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project — you know, the whole reason to worry about nuclear annihilation in the first place. Evidently they were feeling kind of bad about the whole probable destruction of the Earth thing and wanted some way to impress upon people just how bad off the human race actually was. So they commissioned artist Martyl Langsdorf to create the cover art for the June 1947 edition of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Initially Langsdorf wanted to design the cover around the symbol for uranium, but that wasn't really enough to trigger incontinence in the average person, so instead she hit on the idea of a clock. Now, like Cinderella at the ball, prisoners awaiting execution, and people waiting in line on Black Friday (hey you do know you can shop online, now, right?), everyone can all stare at the Doomsday Clock and anticipate our own deaths instead of leading boring, unburdened lives. Thanks, scientists!

From Seven Minutes to Three Minutes

The first Doomsday Clock was set to seven minutes to midnight. The choice was representative of global consciousness during 1947 and was based on a complicated algorithm that considered facts, theories, and the political climate. Just kidding. Martyl Langsdorf said she chose seven minutes to midnight because "it looked good to my eye" (via The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists).

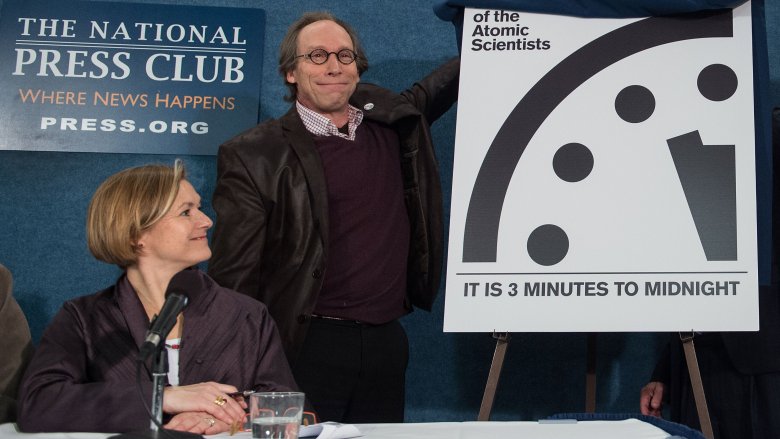

At some point scientists at the Bulletin decided the clock would be even more terrifying if the hand appeared to be moving closer to midnight, so in 1949 the magazine's editor, Eugene Rabinowitch, moved the hand forward a full four minutes, which seems pretty unfair given that it had only been a couple years since anyone had ever heard of the stupid thing, and everyone was still getting used to the idea. So that terrifying seven minutes turned into a hysteria-inducing three minutes, and the scientists presumably all laughed maniacally and then went off to reanimate corpses with lightning or something.

Actually they did have a fairly good reason to be concerned — in 1949 the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb. According to History, the scientists made this choice as a way of announcing to the world the start of the arms race, sort of like if you sent out graduation announcements but your alma mater was the University of We're All Gonna Die.

The Doomsday yo-yo

The Bulletin likes to keep us guessing by moving the clock's hand back and forth and back and forth in an endless parody of "Hey we're about to die!" to "Hey we're almost about to die!" to "Hey we're about to die but just not as soon as we originally thought!" And it's been ever so much fun, like riding on a roller coaster with a bunch of missing track that someone just vomited all over.

The number of minutes left to live has been changed over 20 times since 1947, according to timeline as of 2021. For 2020, the clock came "closer than ever," with a time marking "100 seconds to midnight." Editor John Mecklin noted that nuclear war and climate change were "two major threats to human civilization," compounded by the presence of cyber warfare. Board President Rachel Bronson added, "As far as the Bulletin and the Doomsday Clock are concerned, the world has entered into the realm of the two-minute warning, a period when danger is high and the margin for error low."

Seriously, didn't anyone ever think to tell the Bulletin that their idea totally sucked?

Who gets to decide what time it is?

At this point you might be wondering why you should pay attention to the Doomsday Clock. It's just a bunch of propaganda by a few unknown scientists who think too much of their own opinions. Except whoops, it's actually not a few unknown scientists: It's 15 Nobel Laureates (among others), which means it's pretty likely that they know exactly what they're talking about, even if they do have high opinions of themselves. And really, if you're a Nobel Laureate don't you sort of get to have a high opinion of yourself by default anyway?

According to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the Science and Security Board is the main body responsible for the position of the Doomsday Clock's hands. They have "deep knowledge of nuclear science and climate science," and they also tend to be the people who give scientific and technological advice to other nations and international agencies. So not only are they very smart people, they're very smart people with power and influence, which makes them pretty hard to ignore. And they clearly believe in the righteousness of what they're doing — you know at least one of them will be crawling back to the ruins of the Bulletin's editorial offices, through the ashes of Armageddon, just so they can make sure the clock got set to midnight.

When the Doomsday Clock was furthest from apocalypse

In 1991, the Science and Security board figured it was 17 minutes to midnight until the apocalypse, according to the Doomsday Clock timeline. That's the farthest the clock has ever been, which really doesn't seem very far at all. If you think of doomsday as midnight on New Year's Eve, then 17 minutes before midnight is when you're getting your champagne out of the fridge and making sure everyone you love is all together, and you're settling down in front of the clock so you don't miss anything. Sort of like doomsday, actually, because what else are you going to do besides get drunk with the people you love and watch the bombs go off?

Anyway at 17 minutes to midnight you're pretty much aware that the jig is up, and you're just waiting for it to be over, so the Science and Security board wasn't really making anyone feel warm and cozy by moving the hand all the way back to 17.

What made scientists so partially optimistic (but not really) back in 1991? According to the World Atlas, that was the end of the Cold War and the beginning of non-hostile cooperation between America and the Soviet Union, and for a few minutes it even looked like maybe both countries would be reducing nuclear arsenals. By the end of the year, the Soviet Union had also dissolved. So yeah, the world was much, much safer. That was sarcasm, in case you're a little behind.

Two minutes to midnight

In 1953, Eugene Rabinowitch wrote an article for The Bulletin, which began, "The hands of the clock of doom have moved again. Only a few more swings of the pendulum, and, from Moscow to Chicago, atomic explosions will strike midnight for Western civilization." Very theatrical. The only thing missing was a horse to swap for a kingdom.

What prompted Rabinowitch's Shakespearean musing about pendulums and near-certain annihilation? It was the dual pursuit of even bigger bombs by the United States and the Soviet Union. The prior year, the U.S. decided nuclear wasn't good enough, transitioning to full hydrogen (via History). And then to prove the awesomeness of America, the military also blew up an entire islet in the Pacific Ocean with a thermonuclear device. Nine months later the Soviet Union was all, "Oh yeah? Well, we can do that, too," and then they tested a hydrogen bomb. Now, this was unnecessary, because even a 5-year-old can grasp the concept that you don't really need to blow up the world more than one time, as once will pretty much do it. But there you go. Two minutes to midnight, as per the timeline.

The Cuban Missile crisis

Now, in retrospect, the world was probably like 15 seconds to midnight during the Cuban Missile Crisis, but happily the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists didn't explicitly get to tell us that by gleefully unveiling the next version of their clock with its hands almost vertical. In 1962, the clock was set to seven minutes to midnight, as it hadn't changed from the 1960 designation, as per the clock's timeline.

In January 2017, Lawrence Krauss, who is the former chairman of the board of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, told NPR that the board doesn't put a lot of weight onto individual events (except, evidently for the exploding of small islands in the Pacific), preferring instead to base their decision on global trends and the political climate. And there was also the problem where no one really knew what was happening during the Cuban Missile Crisis until it was over, so the Bulletin kindly decided not to freak everyone out by changing the clock based on an event that was already in the past.

Destroying the planet in lots of different ways

Up until 2007, the only thing the Doomsday Clock and its co-conspirators measured was the threat of nuclear war because for most of that time, nuclear war was the only disaster people could really imagine that might actually destroy the entire planet and everyone on it. Then climate change came along.

That year, when the Bulletin moved the hands forward from seven minutes to midnight to five minutes to midnight, they cited the rise of "a second nuclear age" and, for the first time, climate change. "Damage to ecosystems is already taking place; flooding, destructive storms, increased drought, and polar ice melt are causing loss of life and property," they wrote. That was also the year they began to measure the likelihood of dead people crawling out of their graves and hungering for the flesh of the few still-living humans huddled together in bunkers and former maximum-security prisons. Just kidding. For some reason, they're still not taking the approaching zombie apocalypse into consideration. Won't they feel so stupid when that happens?

A fatalistic design

The really annoying thing about the Doomsday Clock is its design — most of the time, it's depicted just as the upper left quarter of a clock, which implies that the timeline will always be pretty much within the last 15 minutes of life on Earth. That seems pretty unapologetically fatalistic, but maybe the board is worried that people will become hopeful if they show us the whole clock, and nobody wants that.

Besides being a not-very-objective look into the future, the clock's design has some fundamental problems — most notably the absence of a point of reference that people can use to actually gauge how dire two minutes, five minutes, or 10 minutes actually is. Where, for example, would the clock have been during Paleolithic times? 11 p.m.? 7 a.m.? And what does that say about the fate of the neanderthals, because it was basically doomsday for them at that point, wasn't it? Would they get their own clock?

According to Wired, Eugene Rabinowitch explained it like this: "[The clock] is intended to reflect basic changes in the level of continuous danger in which mankind lives in the nuclear age." Okay, but just give us a baseline. You guys are scientists. It shouldn't be that hard.

Back to Two Minutes

In January 2018, the board moved the hands back to two minutes to midnight, as per the clock's timeline, which you'll remember was the 1953 level that foreshadowed "a few more swings of the pendulum" and BOOM.

So what compelled the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists to move us all the way back to Cold War levels of potential Armageddon? The board said it was "the failure of President Trump and other world leaders to deal with looming threats of nuclear war and climate change," as reported by The Washington Post.

But that's not all ... the board's long list of reasons reads like roll call for the Pandora's Box School of Things that Might Destroy the Human Race: North Korea's missile program, the frosty relationship between the U.S. and Russia, Iran's nuclear ambitions, the internet and all its misinformation, and sentient killer robots. No really, that last one was totally in there, though they used somewhat tamer language: In their statement (via The Evening Standard), they mentioned artificial intelligence as one of the many technological innovations that might bring down civilization.

Is the Doomsday clock accurate?

Obviously, the Doomsday Clock isn't accurate. Otherwise everyone would have exploded at midnight the day after the June 1947 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Sciences hit the newsstands. The world is still here, so "accurate" is probably not the right adjective.

According to Wired, the Doomsday Clock is symbolic. It's not meant to be predictive — rather, it's a warning that is supposed to motivate us into action. The clock's original purpose was just to get everyone's attention, and it's certainly succeeded in doing that. And every time they move the hand forward or backward, that gets our attention, too. So no matter how hard people try, it's really hard to forget about the Doomsday Clock.

Is it the right kind of attention, though? Scientists hoped the Doomsday Clock would inspire everyone to get up and collectively work toward real, positive change ... on the other hand, it's unclear exactly how that will happen when people are all cowering under our beds.

Not everyone thinks predicting the apocalypse is a great idea

Not everyone thinks the Doomsday Clock is totally cool. Well ... no one thinks the Doomsday Clock is totally cool, but that's not the point. Over the years, critics have made arguments ranging from "scaring people isn't very productive" to "the data is all wrong." In 2015, Anders Sandberg wrote for The Conversation that there's really no way to estimate the probability of global annihilation, because there are too many subjective factors. In other words, you can't make accurate predictions based on assumptions.

The Doomsday Clock scares us because it was designed to. According to The Breakthrough, the scientists who gifted us the holy terror of an apocalyptic time-keeping device did it because they wanted to convince us that the threat of global annihilation was real enough to demand our attention — sort of the scientist's equivalent of standing around on street corners with a clapboard, only more terrifying because those aren't actually just insane people holding clapboards, they're Nobel Laureates.

But critics think that's going too far. Some say the focus on apocalyptic scenarios distracts us from smaller risks that could eventually add up to The Big Bad. Other critics think predicting the end of the world really does nothing but paralyze everyone into inaction. It's much easier to pop that bottle of champagne and watch the end come than try to find a solution with the help of a whole world full of reluctant humans.

It's time to dig a bunker and stock up on canned food

Now that you've got a shovel in one hand and a truckload of Dennison's chili sitting in your driveway, here's some reassurance — the clock can be turned back again, and the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was kind enough to tell us how. In their 2020 statement, they urge U.S. and Russian leaders to essentially ben ice to each other and work together, for countries to "rededicate themselves to the temperature goal of the Paris climate agreement," and for citizens to further demand government take major action on climate change. Furthermore, governments all over the world can commit to policies aimed at preventing cyber warfare that undermines and threatens democracy.

"We believe that mass civic engagement will be necessary to compel the change the world needs," writes editor John Mecklin. So do your part as a concerned citizen, sure, but make sure you also have some champagne stashed away in that bunker so you can lift a glass when the end of the world finally arrives. You're gonna need it.