Freddie Mercury's Tragic Real-Life Story

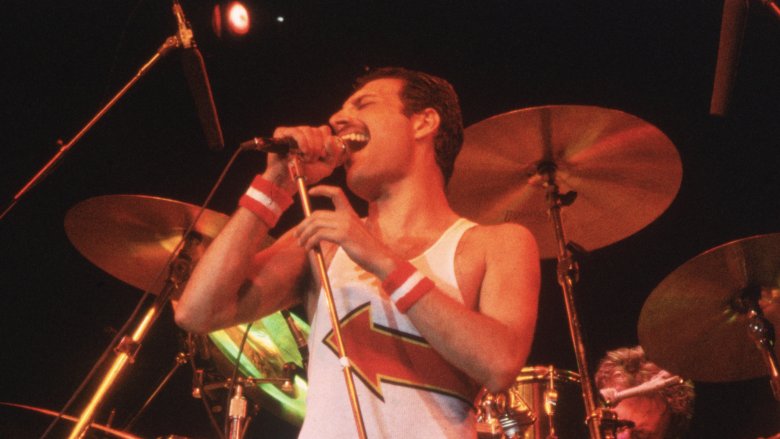

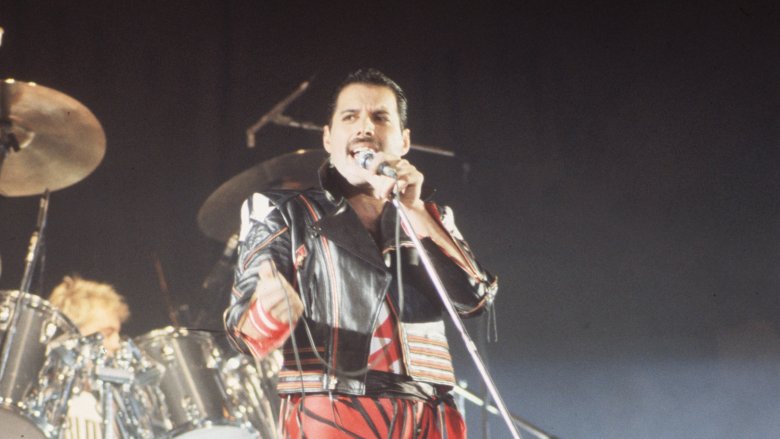

When you hear the words "rock icon," a few names probably come to mind. Elvis Presley. The Beatles. Janis Joplin. Freddie Mercury. Artists come and go — some of them achieve fame and fortune, but never become legends. And the ones that do often find themselves either struggling to live up the public's idealized image of them or just letting the public think what they will. Freddie Mercury was in that second category.

Always flamboyant, energetic, and controversial on stage, Mercury was famous off stage for his reclusiveness and desire to keep his private life private. In public he was a force of nature, but he was intensely shy and lived his life in secret — he even died in secret, hiding the truth about his illness from everyone, including those closest to him, until the final few hours of his life.

Freddie Mercury's life was tragic, but it was phenomenal, too. Years after his death, his music still draws new fans, and the public finds him as fascinating as ever. In a lot of ways, that's exactly what he wanted. "You can do what you want with my music," he told his manager just a few days before his death. "But don't make me boring."

You only wish your parents were that cool

Just in case you're wondering what sort of awesomely cool parents would name their kid "Freddie Mercury," that's not his real name. (Yes, shocking.) Freddie Mercury was born Farrokh Bulsara, which would have been a pretty good rock star name in the modern world but in the '80s, not so much. His family was Parsee — ethnically Persian followers of the Zoroastrian religion. He spent part of his childhood in India and part in colonial Africa, but in 1963 his family was forced to flee Zanzibar to London after the country achieved independence and poor Africans started targeting wealthier Indian families.

In London, Mercury, who was given the nickname "Freddie" by teachers in India, enrolled in graphic design classes at Isleworth Polytechnic. His mother, Jer Bulsara, told The Telegraph that she made him apply for graphic design jobs between all the songwriting he was doing while holed up in his bedroom. "Had he got one of those jobs, things would have been quite different." Instead, he pissed off the neighbors with all the noise and moved out.

"I am proud for everything that comes up for my boy," his mother said. "The whole world seems to know him. They know who Freddie Mercury is. My boy was a genius." So in case you're still wondering what sort of awesomely cool parents he had, there you go.

And then Bucky became famous and ruled the world

You know that kid at school who got teased because of some little physical oddity, like large ears or being super tall? What if that kid went on to become a superstar and that weird little oddity had something to do with it? Basketball star? Person who hears really well? Wouldn't that make everyone who was cruel feel some well-deserved remorse?

According to Rolling Stone, when Freddie Mercury enrolled in Peter's Church of England School in Panchgani, India, he was really self-conscious about his prominent upper teeth, and because children are cruel little imps, his classmates caught onto this particular insecurity and gave him the name "Bucky." And because childhood trauma will haunt us all for the rest of our lives no matter how much therapy we get or how famous we become, Mercury developed an insecurity about his teeth that lasted pretty much his entire life — even after he became a star, he would cover up his mouth with one hand whenever he smiled. Some people think his teeth might have actually contributed to his distinctive singing voice, so we can all feel a sense of righteous spite on Freddie's behalf knowing that someone out there is harboring a horrible secret: "I called Freddie Mercury 'Bucky' and then he became rich and famous and I ended up getting a nowhere job in graphic design." Ha.

Fame sometimes has too high a price

If Freddie Mercury had become a star in the 2010s instead of in the 1980s, his story would have had a different ending. Sure, our world still has a lot of homophobia in it, but in general there's a lot more support for people who don't conform to heterosexual gender roles. So maybe he would have come out. He almost certainly wouldn't have died. But that's not what happened.

According to The Advocate, Mercury probably became infected with HIV in New York in the summer of 1982. The 2016 book Somebody to Love: The Life, Death, and Legacy of Freddie Mercury, suggests he was already showing symptoms when he appeared on Saturday Night Live in September of that year in what would be his last U.S. performance. Unfortunately, HIV/AIDS was still a very new thing in the early '80s, publicly associated with gay men and the gay lifestyle, and Freddie Mercury was not open about his sexuality. Homophobia in that decade was vicious, and the rise of the AIDS epidemic made religious zealots feel justified in attacking gay men both verbally and physically. So Mercury kept quiet, and some of those fears affected the treatment he sought, the people he told, and his decision to stop appearing in public.

The coming-out song that never came out

Freddie Mercury considered "Bohemian Rhapsody" to be his greatest achievement, but decades later we're still arguing about what the song actually meant. Mercury himself was pretty cagey about it. According to Rolling Stone, he once answered a question about the song's meaning with these words: "I'll say no more than what any decent poet would tell you if you dared ask him to analyze his work: 'If you see it, dear, then it's there.'"

A lot of people seem to think "Bohemian Rhapsody" is a coming-out song, though if that's the truth it is so deeply disguised in metaphor that only a resurrected Freddie Mercury could say for sure. One music scholar even suggested that the line "Mama, just killed a man" refers to the metaphorical death of straight Freddie Mercury at the hands of gay Freddie Mercury, which sounds a bit like the conclusion you might come to if you really, really wanted the song to be a coming-out ballad but couldn't decide which line actually supported your theory. But it is also true that at least one person who knew him — manager John Reid — said he thought "Bohemian Rhapsody" might have been a coming-out song, though everyone seems to forget that Mercury never actually "came out." If it was a comment on his sexuality it doesn't seem to have been intended as an overwhelmingly public one.

Mercury wasn't straight, but he might not have been gay, either

Viewed backward through a historical lens that bypasses pretty much everything we've learned about sexuality since people stopped covering up their ears and chanting "la la la I can't hear you" whenever anyone tried to have a rational discussion about it, it would be easy to pigeonhole Freddie Mercury as a closeted gay man, but he was a lot more complicated than that. In a 2016 issue of The Advocate, Diane Anderson-Minshall wrote about the fundamental problem with trying to overanalyze Mercury's relationship with former girlfriend Mary Austin. The authors of Somebody to Love attempt to explain why he might have put Austin above all of his gay relationships as having something to do with his own deep-seated homophobia, but maybe he was really just bisexual. Sometimes, as Anderson-Minshall pointed out, we're too eager to categorize people as either gay or straight, without acknowledging that sexual orientation isn't always that black and white.

Mercury referred to Austin as "the love of his life" and his "common-law wife." As romantic partners they were together for seven years, splitting up when Mercury started pursuing relationships with men. Even then they remained close. He left most of his estate to her when he died, and he also entrusted her with secretly scattering his ashes.

Friends will be friends

Freddie Mercury did not want anyone to know he had AIDS. In those days it was deeply stigmatized, so his desire to maintain his privacy was not really that shocking, even if you consider that he kept the secret from nearly everyone, including those closest to him. Freddie's partner Jim Hutton said the statement issued the day before Mercury's death, in which the singer finally publicly announced he was dying from AIDS, was not something Mercury had either written or authorized. "I don't think he would have wanted it," Hutton said. "He wanted his private life kept private." And his family says they were aware Mercury was very ill, but he didn't tell them why. Brother-in-law Roger Cooke told The Daily Beast, "Freddie said: 'You have to understand that what I have is terminal. I'm going to die.' He didn't say it was AIDS."

With some people, Mercury was almost irrationally secretive. In Somebody to Love, his close friend Peter Straker remembers Mercury telling him he had "this blood thing." "He started to get these blotches and I asked about these ... and I said to him, 'Have you got AIDS?' and he said, "No, I haven't got AIDS.' And I said, 'If there's anything wrong with you, I'm always here for you,' and we parted that evening. That was the last time I saw him.'" Straker made repeated attempts to contact his friend after that but was always refused.

'Thank you, good night.'

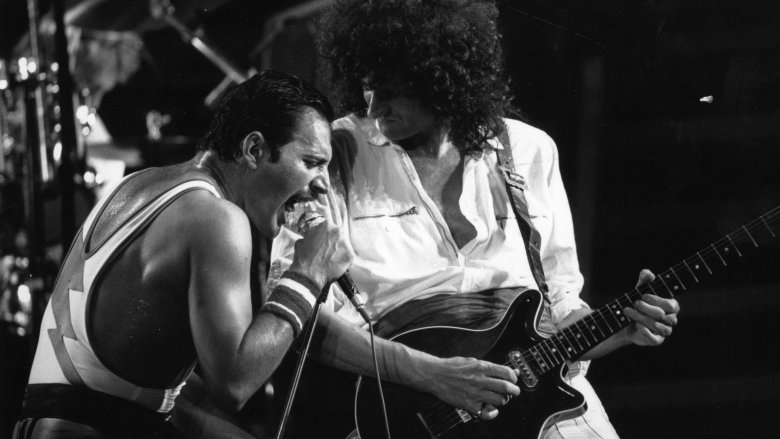

The tabloids spent a lot of time speculating about Freddie Mercury, just as they spend a lot of time speculating about alien abductions and calamari-induced pregnancies. The Sun in particular was pretty cold-blooded when it came to Mercury/AIDS gossip and was publishing sensational headlines about the singer's supposed diagnosis before Mercury even had a diagnosis. Like everyone else in Mercury's life, his bandmates dismissed the gossip and remained largely ignorant when it came to their front man's health problems. In 1989, Mercury decided he "wasn't up to doing tours," so the band didn't schedule one following the release of their album The Miracle. "We never talked about it and it was sort of unwritten law that we didn't," said guitarist Brian May in an interview years after Mercury's death. "Gradually, I suppose in the last year and a bit, it became obvious what the problem was, or at least fairly obvious. We didn't know for sure."

According to Ultimate Classic Rock, by 1990, Mercury was gaunt, sickly, and clearly not himself. His final public appearance was at the Brit Awards, when Queen accepted the award for Outstanding Contribution to British Music. The acceptance speech was given not by Mercury, as everyone expected, but by May. Mercury only said "Thank you ... good night" just before the band left the stage.

'I'm sorry I've upset you'

Kaposi's sarcoma is a rare form of skin cancer that started appearing in small populations of gay men in the early 1980s. Since it was previously known to occur mostly in older people with Mediterranean or Middle Eastern heritage, the sudden clustering of cases in young gay men was baffling until someone linked it to the HIV virus. Today, Kaposi's sarcoma is considered an "AIDS-defining illness," which means an HIV-positive person who develops it is considered to have AIDS.

Freddie Mercury started to develop Kaposi's sarcoma on his feet, hands, and face. By the time he died, his friend Elton John remembered him "covered with Kaposi's sarcoma lesions." And complications from the disease also caused him to lose most of his foot. "Tragically, there was very little left of it," guitarist Brian May told the Sunday Times magazine in 2017. "Once, he showed it to us at dinner. And he said, 'Oh Brian, I'm sorry I've upset you by showing you that.' And I said, 'I'm not upset, Freddie, except to realize you have to put up with all this terrible pain.'"

Even so, Mercury rarely discussed his illness or what was behind it. Speaking to Entertainment Weekly, drummer Roger Taylor said, "He didn't want to be looked at as an object of pity and curiosity, and he didn't want circling vultures over his head." In a way, that helps explain how such a huge personality could have faded so quietly from the public eye.

The groundbreaking treatment that came too late

Freddie Mercury was one of the first celebrities to die from AIDS, but his death also happened when medical science was on the brink of discovering a treatment that would change AIDS from a death sentence to a manageable, long-term, chronic illness. Today, patients are treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), which helps prevent them from developing serious AIDS-related complications. HAART is a triple drug therapy that entered most clinical practices in 1996, just five years after Freddie Mercury's death. Bandmate Brian May (above) told the Sunday Times that Mercury missed the "magic cocktail" drugs "by just a few months," and he feels sure that Mercury would still be here if he'd only been able to hang on a little longer.

It's important to remember that although people in the Western world have access to the HAART therapy, the treatment is expensive and not available to most of the people in AIDS-devastated parts of the developing world; more than 18 million children who have lost one or both parents to the disease. So while it is true that it could have saved Mercury, it could be saving millions more even today, if only it could be made affordable and accessible.

Can't you just leave a dying guy alone?

On the scale of "mostly not-evil" to "express ticket to hell," the paparazzi rank just above internet trolls as some of the more evil people who are not in jail. Paparazzi get paid to follow celebrities around and take pictures of them in their most vulnerable, private moments. They've even indirectly (or directly, depending on your perspective) caused a celebrity death or two — in 2006, nine photographers were famously charged with manslaughter (and later acquitted) after Princess Diana was killed in a car accident while trying to escape them in 1997.

Freddie Mercury was also plagued by paparazzi — according to The Advocate, they even stalked him during the final days of his life, hoping to capture a last photograph of him in his gaunt and frail state. Terry Giddings, who served as Mercury's bodyguard and driver, remembers photographers lined up in front of the singer's home "like a pack of wolves waiting for the carcass to come out." And after Mercury finally succumbed, the press pretty much figured it was open season. One Daily Mirror columnist called Mercury "sheer poison" and went on to say AIDS was "a form of suicide for homosexuals." Okay, maybe he wasn't technically a paparazzo, but yeah, still going to hell.

Posthumous achievements

Freddie Mercury can't really be said to have "raised AIDS awareness" in the same way that other, much more vocal HIV-positive celebrities like Magic Johnson and Rebekka Armstrong have. He wasn't open about his illness and he barely even publicly acknowledged it. (He might not have acknowledged it at all, depending on whether his final statement was in his own words or someone else's.) That was certainly his right, and it's probably not up to us to criticize him for that, even after his death. But there's no question that the singer's battle with the disease had a profound effect on the public's awareness of HIV and AIDS.

After his death, Brian May, Roger Taylor, and band manager Jim Beach formed the Mercury Phoenix Trust in Freddie Mercury's memory. The organization raises money for HIV/AIDS initiatives all over the world — according to its website, since it was established in 1992 it has raised more than $16 million for more than 700 HIV/AIDS-related projects. Freddie Mercury might have been private about his own struggle with the disease, but his legacy and memory have contributed significantly to the worldwide battle against the illness. And that's an accomplishment that even outshines "Bohemian Rhapsody."