Bizarre Things These Saints Were Buried With (Or Next To)

For many of those in the Catholic and Orthodox Christian churches, saints can be an important part of their faith. The idea is that when particularly holy people die – those who suffered for their beliefs or died fighting for them or even were just super awesome and kind individuals – they get the chance to become a saint.

This process involves getting promoted through different levels of pre-sainthood that come with other titles like "venerated" or "beatified." But if they pass all the tests, including at least two verifiable miracles that the Church investigated and confirms, the pope can sanctify them. Then they get a nice "St." in front of their name, and possibly become a patron of something no one else has claimed yet, like ... water bears or TikTok, maybe? And the faithful can pray to the saint and ask for help or intercession with God.

It makes sense that a religion would want to hold up the most perfect examples of their followers and give them special recognition. But in reality, when you start looking into the lives of saints, some very weird stuff emerges. Many were not all that holy, if they even existed, and their deaths were often almost comically ridiculous. It didn't stop there, either. Sometimes, the strangeness of a saint's life followed them to the grave, literally. Here are some of the bizarre things these saints were buried with or next to.

St. Cuthbert

St. Cuthbert was an English bishop who lived until 687 and, according to Bede's "Life of St. Cuthbert," was said to perform miracles even before he died — which is when many future saints started showing off their supernatural powers. While Cuthbert is quite famous, especially in the U.K., if you're not familiar with him, don't worry. When you walk into a church or art museum, he's pretty easy to pick out — he's the saint carrying another guy's head, the head of St. Oswald, to be precise.

Unfortunately, that's not just a piece of symbolism or metaphor represented through art. When Cuthbert died, he was buried at his monastery, Lindisfarne, however, over the next 400 years, his body was disinterred and moved around repeatedly, per The Catholic Encyclopedia. In 1104, the people doing the moving got a surprise: Cuthbert's body was now keeping company with the head of St. Oswald, the long-dead king of Northumbria.

While Oswald and Cuthbert lived in the same area, their lives only overlapped by a decade or less, with Cuthbert estimated to have been a young child when Oswald died. But like his fellow saint, Oswald's body wasn't laid to rest permanently, getting moved around over the years. At some point, the remains of the two finally ended up in Durham Cathedral at the same time, and Oswald's head was put into Cuthbert's grave. (Other bits of the late king were spread around, including his arm, which was displayed further south at Peterborough Abbey.) Sadly, the remains of both saints have since been lost.

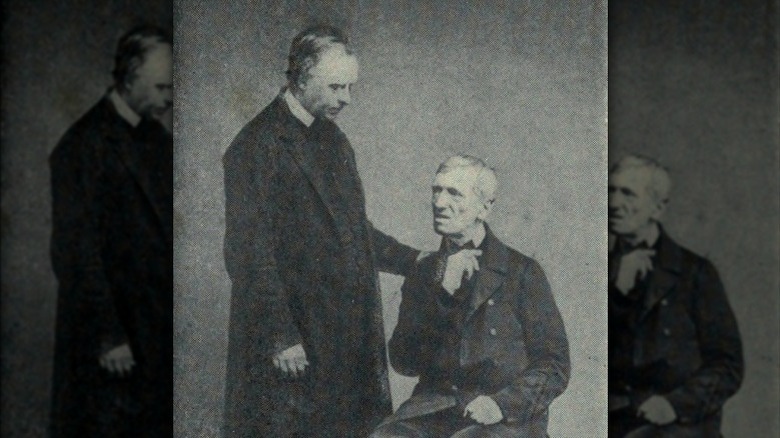

St. John Henry Newman

St. John Henry Newman was an academic who converted to Catholicism from the Church of England, per The Catholic Encyclopedia, eventually making it all the way up the hierarchy to cardinal. He died in 1890 and was made a saint in 2019. However, his last wish has made him one of the more controversial figures in the church.

Many people, including Catholics, think Newman was gay, which would mean the church canonized a gay man. There's plenty of evidence Newman was deeply in love with his friend and companion Ambrose St. John, but arguments around what kind of love it was, exactly, or if they ever had a physical relationship of any kind. What is known for sure is that, with his friend predeceasing him, Newman put in writing more than once what he wanted after his own death: "I wish, with all my heart, to be buried in Father Ambrose St. John's grave – and I give this as my last, my imperative will" (via "John Henry Newman: Meditations and Devotions").

When preparing for Newman to be canonized, his body was moved from the men's shared grave. This was just as controversial. "The Vatican is guilty of historical revisionism. ... Digging up Newman's grave and separating the two men was an act of sacrilege, betrayal, disrespect and homophobia," human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell wrote. However, writing in The Guardian, Mark Vernon opined that saying the saint was gay "distorts and abuses the significance of Newman's last act, which was actually about friendship."

St. Casimir

St. Casimir was a Polish prince before he died in 1484, aged around 25, from a problem with his lungs, per The Catholic Encyclopedia. He was canonized in 1522, but by the turn of the 21st century, Pope John Paul II was still holding up this young man as an example for young people, saying that Casimir "embraced a life of celibacy, submitted himself humbly to God's will in all things, devoted himself with tender love to the Blessed Virgin Mary" and "His life of purity and prayer beckons you to practice your faith with courage and zeal, to reject the deceptive attractions of modern permissive society, and to live your convictions with fearless confidence and joy" (via the Catholic News Agency).

Now, a young prince dying tragically might get some modern teens excited, but the celibacy aspect might give them a bit of pause. Fortunately, Casimir had something else they can relate to: a love of music, specifically, one awesome tune. Casimir was so into the hit hymn "Daily, Daily Sing to Mary" that for centuries it was believed he actually wrote it, as The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology explains. But the fact that it's now attributed to someone else – Bernard of Cluny – just makes it even better that Casimir was so obsessed with the song. Apparently, he was constantly singing it, like the biggest BoC stan there ever was. Casimir's love of the tune was such that when he died, he was buried with a copy.

St. Vincenzo Martyr of Craco

St. Vincenzo, Martyr of Craco, was a soldier with the Theban Legion, which was on its way to help put down a revolt in 286, according to the modern society that bears his name. While the Romans they were campaigning with were not Christians, the Legion was. However, this shouldn't have been a problem, since by this period, the new religion was becoming so popular that martyring followers of Christianity was going out of style. Sadly, no one told this to the Legion's commanding officer Maximilian, apparently, or he just wasn't worried about looking cool.

Wanting to guarantee they were able to crush the barbarian uprising in what is now France, when the soldiers camped in Italy on their way there, Maximilian told all of the men to make an offering to the Roman gods. The Christians refused. Maximilian responded by ordering the Legion to be "decimated," in the technical sense of the term, meaning 10% of the men were killed — although Maximilian actually ordered a second round of decimating when the first one wasn't effective. One of the many killed was St. Vincenzo.

Described by The Craco Society as the "sacred body with a flask of blood," St. Vincenzo would have been identified as a martyr centuries later when his body was found, most likely in a catacomb, accompanied by an ampullae of reddish liquid. Bodies with these flasks were said to be saints buried with their own blood as a forward-thinking, pre-packaged relic, although testing has shown the liquids are not actually blood.

St. Babylas of Antioch

According to The Catholic Encyclopedia, St. Babylas was a bishop in the Eastern Roman Empire who had the bad luck to live during the first-ever empire-wide persecution of Christians. This became known as the Decian persecution, after the emperor who decreed it. The story of his martyrdom varies a bit in early accounts, but the main legend is that after the emperor killed a child or committed some other heinous crime, Babylas refused to let him enter his church. The emperor was embarrassed and shamed by this rejection, so he had Babylas arrested.

Here again, accounts vary. Some say Babylas was executed, while others record he died in prison after being tortured, but not explicitly killed. What all seem to agree on, however, was that while under arrest, Babylas had been bound in chains — and he insisted those chains be buried with him when he died as a sign of his martyrdom, according to "Apologies," a collection of 4th-century writings by Saint John Chrysostom. Later, in honor of his sacrifice and steadfast faith, a church was built over his grave.

However, there was a famous oracle who did business next to the church, and when, years later, a different emperor came to the oracle and asked to know the future, he was told this was impossible. As St. John Chrysostom recorded (via Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America), the oracle explained, "The dead prevent me from speaking." Taking this to mean the remains of the saintly Babylas were a problem, the emperor had them moved, which was when the chains were discovered with the body.

St. Damien De Veuster of Molokai

Few things could turn moving to Hawaii from a dream to a nightmare, but living in a leper colony was definitely one of them. But after spending eight years as a priest on the big island, the then-Father Damien volunteered for the job. It would end up killing him.

The Hawaiian islands had many people with Hansen's disease, commonly called leprosy, and those infected were moved to the island of Molokai by colonizers and, effectively, left there to die. Father Damien hoped to improve that — if he could stay healthy himself. He wrote to his brother in 1873, "I have been here six months, surrounded by lepers, and I have not caught the infection. I consider this shows the special protection of our good God and the Blessed Virgin Mary" (via an 1889 edition of The Month).

While Damien saw the native Hawaiians as inferior, he worked hard to make life better there and was completely hands-on. He even spent regular time in the cemetery, watching over those who had lost the battle, writing, "I am the sole watchman of this fine garden of the dead — all my spiritual children — I find my pleasure in going there to say my rosary..." (via "Holy Man: Father Damien of Molokai). Damien eventually caught leprosy. He died in 1889 and was buried in a plot he'd picked out in that same cemetery, surrounded by the people with leprosy he'd ministered to.

St. Ursula

There is very little information about St. Ursula that isn't legend; in fact, it's unclear if she actually existed. The estimated year of her death varies greatly, from 383 to 451. But that's probably a good thing, since it would be one of the greatest tragedies in history if Ursula died and was buried the way most of the legends claim.

Ursula was a princess from what is now Great Britain, and a devoted Christian. But as a princess, she had to marry and didn't have a choice who the man was. When a pagan prince asked to make her his wife, she begged her father to delay it a few years so she could go on a pilgrimage. He agreed, and she took off for the Continent with some attendants, all virginal women.

How many attendants? Well, even though the whole legend comes from 10 lines carved in the wall of a French church, which do not give a number, over the years stories were added to it, and in the end, Ursula had 11,000 virgins on the pilgrimage with her. Unfortunately for what would have been a significant chunk of the young women of Britain at the time, when they were in Europe, they were all martyred for their faith and buried together with Ursula, according to "The Cult of St. Ursula and the 11,000 Virgins," edited by Jane Cartwright. There are various theories about where this huge number comes from, with experts theorizing it was a translation error or simply a change made in sermons to make the story more dramatic.

St. Francis Xavier

St. Francis Xavier is famous for being one of the first Jesuits and for his extensive missionary work, especially in the Far East, according to The Catholic Encyclopedia. In fact, it was while in that part of the world that he died in 1552. In a time when refrigeration and effective embalming did not exist, it was not strange for people to go to extreme lengths to transport a body when the individual in question died far from home.

So when this holy man died on Shangchuan Island, those with him decided to bring at least what remains they could back with them. This is why St. Francis Xavier was buried in a manner usually found in murder mystery books, when a killer is trying to make a body disappear: "George Alvarez undertook to put the body into a large Chinese chest. He caused it to be filled with unslaked lime, that the flesh being quickly consumed, the bones might be more conveniently brought in the vessel, which in a few months was to return to India" (via "The Life of St. Francis Xavier, of the Society of Jesus, Apostle of India").

However, this only proved that Xavier was saint material, since it didn't work. When they dug him back up, "The vestments in which the body lay, were nowise injured by the lime; and the body itself exhaled so fragrant and delightful an odor, that many present declared that the most exquisite perfumes were not to be compared with it."

St. Cosma and St. Damian

Unlike most people who are eventually made saints, according to The Catholic Encyclopedia, Cosma and Damian were not holy men in the traditional sense; they were doctors, but because they were such successful healers who always refused payment for their services, their goodness ended up bringing many of their patients to the Christian faith, per "A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines." However, they were so dedicated to taking nothing of monetary value for their work that it led to what could have been an eternal separation for the pair.

One old woman, who had never found a successful treatment for her ailment before, insisted that Damian accept a few eggs in return for curing her, saying, "Take this small gift in the Name of the Holy Life-Creating Trinity – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit." Since she'd invoked the Trinity, Damian didn't see how he could refuse. When his brother found out, it didn't matter the reason: "When St. Cosmo knew it, he commanded that his body should not be laid after his death with his brother's," according to "The Golden Legend."

Things went sideways for the brothers, and they found themselves being martyred. Before they could be buried separately as Cosma demanded, a camel walked by and announced, "Cosmas and Damian cured not only you, men, but us too, wordless animals. Therefore I come, grateful to them, to tell you that the Lord orders you to bury them together" (translated in the Hektoen International Journal). So two brothers who should not have been buried together were, all thanks to a talking camel.

St. Thérèse of Lisieux

St. Thérèse of Lisieux desperately wanted to be a saint, but since she was limited by what she could accomplish in her convent, she concentrated on small humble acts, according to her biography at the Society of the Little Flower.

As Thérèse lay dying of tuberculosis in 1897, aged just 24, one of the other nuns told her that her body would remain incorrupt after she died as a sign of God's love, Thérèse was not happy about the prospect, saying, "Oh, no! That miracle would be to stray away from my little path of humility, and little souls must not find anything in me to be envied" (via "Soeur Thérèse of Lisieux, the Little Flower of Jesus"). She would get her wish.

In the epilogue of "The Story of a Soul: The Autobiography of St. Thérèse of Lisieux With Additional Writings and Sayings of St. Thérèse," a witness to her death wrote: "No sooner had her spotless soul taken its flight than the joy of that last rapture imprinted itself on her brow, and a radiant smile illumined her face. We placed a palm-branch in her hand..." When Thérèse's body was exhumed in 1910, everyone expected her to be incorrupt like saints were supposed to be. But she had turned completely to bones, even her clothes were rotted away ... but the palm frond that had been put in her hand and buried with her was still alive and green.

St. Teresa of Avila

St. Teresa of Avila was famous even in her lifetime, according to The Catholic Encyclopedia. When she died in 1582, she was buried at the convent she had been visiting at the time, and someone wanted to make sure she stayed there. According to the account of Mother Anne of St. Bartholomew, who witnessed the death and burial of Teresa, "Her body was put into a coffin, but such a heap of stones, bricks, and chalk were put on top of it that the coffin gave way under the weight and all this rubble fell in. It was by the order of the lady who endowed the house ... that the rubble was put there. Nobody could prevent her ... she was making all the more certain that no one would take Teresa' body away" (via "The Incorruptibles: A Study of Incorruption in the Bodies of Various Saints and Beati").

The extra dirt might have kept her put, but it couldn't block the pungent but apparently lovely smell that emitted from the grave. Finally, the body was exhumed, and it turned out all that extra dirt helped prove how saintly Teresa was. Jerome Gracián recorded (via the same source) what he saw: "They found the coffin lid smashed, half rotten and full of mildew ... The whole body was covered with the earth which had penetrated into the coffin and so was all damp too, but as fresh and whole as if it had only been buried the day before."