The Deadliest Massacres In Every State

Looking back through the history of America, there has been a shocking amount of mass violence, and it almost seems at times as if violence is an endemic part of the American culture. Even before the founding of the United States, the American landscape often found itself awash in blood, the memories of which still reverberate today.

The word "massacre" is a very loaded term, and oftentimes, it's hard to discern a massacre from a skirmish or battle — and many incidents are known as both. One thing is for certain — a massacre means a slaughter of usually innocent people that's also typically an act of cruelty. Historically, there is often dispute about how many people may have died during any particular event, with some having ranges that span in the hundreds. However, some of the biggest massacres, like the infamous Sand Creek and Wounded Knee, form an important part of the United States' social history, even if they happened in areas that were technically territories and not yet states. But all 50 states have had their share of bloodshed that have become a deadly and indelible mark on their history.

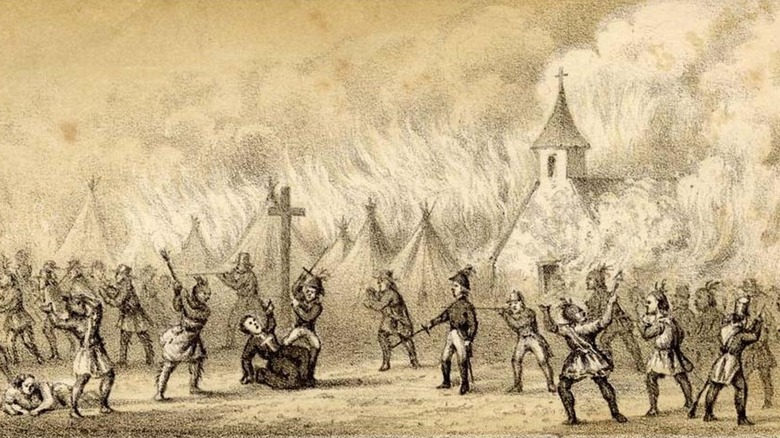

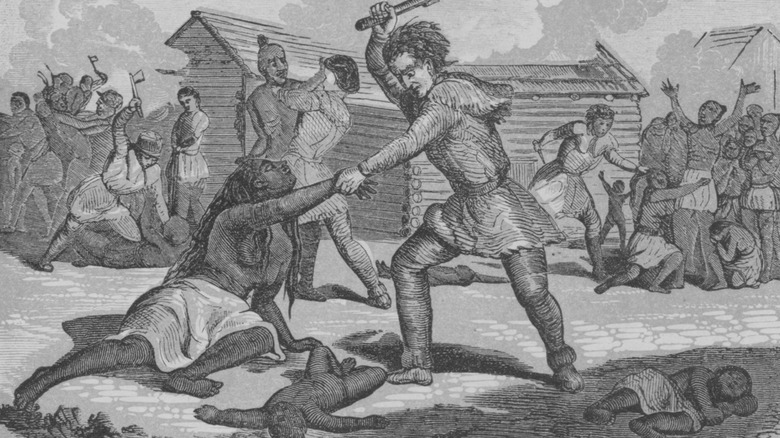

Alabama: Fort Mims Massacre (1813)

The Fort Mims Massacre happened before Alabama was actually a state, during a time when tensions were high between Native Americans and American settlers. The Creek Indians had largely accepted the settlers and had become their political and economic allies, but there was a faction known as the Red Sticks who were vehemently opposed to assimilation. In opposition, they broke off and went to war with the rest of the tribe.

At Fort Mims, which is in present-day Baldwin County, there were rival Creeks, American settlers, soldiers, and enslaved persons, all seeking shelter. The Red Stick Creeks, led by William Weatherford, numbered 700-1,000 strong and attacked Mims on August 30, 1813. Over the course of hours, the war party plundered and razed the fort to the ground, with many victims still inside the buildings. An estimated 250 people were murdered, including soldiers and civilians who were seeking refuge inside. The victims included young children and pregnant women, some of whom were cut open and mutilated. Even Weatherford tried to stop things when he thought they went too far, but he failed to contain the orgy of violence. "My warriors were like famished wolves, and the first taste of blood made their appetites insatiable," he would later say (via the Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

It may have happened a few years before Alabama joined the Union, but it's still incredibly significant, as it played a huge part in the removal of the Creek Nation from what is now Alabama.

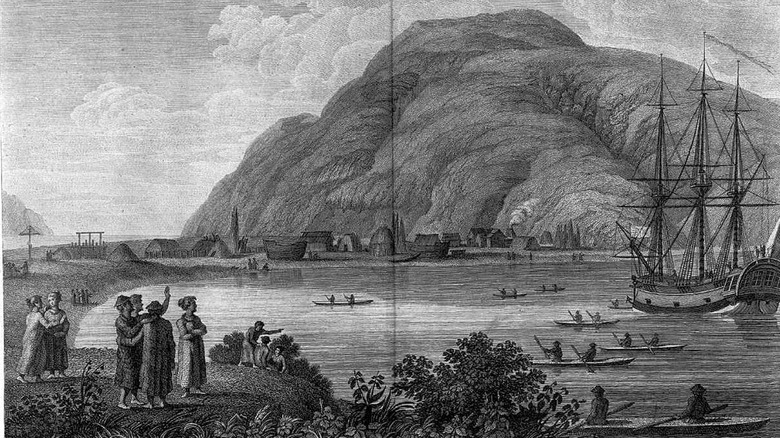

Alaska: Refuge Rock Massacre (1784)

By April 1784, the Russians had been trying to gain a foothold in Alaska for years, but they had struggled to defeat the Aleut and Alutiiq Indigenous people. That all changed when Grigori Shelikhov, a Russian Fur trader and the founder of the first Russian colony in Alaska,brought armed men and cannons to Refuge Rock off of Kodiak Island — a place meant for shelter and safety for the local villagers.

When Shelikhov came, he and some 130 men brutally took down 200-500 villagers (many voluntarily jumping to their death to avoid the Russians' guns), destroying their settlement in the process. An elder of the Alutiiq, Arseni Aminak, confirmed the massacre several decades later, saying the Russians murdered 300 and took the chiefs' children as hostages.

At the time of the attack, the Russian Imperial government had barred violence against the Indigenous people outside of self-defense, so Shelikhov claimed the villagers attacked first, thus saving himself from facing punishment for the killings. Lydia T. Black of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, told the Los Angeles Times that Shelikhov was spoiling for a fight after years of skirmishes between the Russians and the Aleut and Alutiiq tribes.

Often described as Alaska's "Wounded Knee," the massacre marked Russia's expansion into North America that would, ironically, last for less than a century.

Arizona: Camp Grant Massacre (1871)

During Arizona's territorial days, by the late 19th century, American settlers and Indigenous tribes had a volatile peace. While most local Apaches near Tucson were assimilating under the protection of the U.S. Army, some bands still targeted the town during raids, occasionally committing murder. For the townspeople, hostility was so deeply ingrained that they considered all Apaches outlaws, so they decided to retaliate against Aravaipa and Pinal Apache taking refuge near Camp Grant.

White settlers and local Mexicans banded together with the Tohono O'odham tribe (who considered Apaches their enemy) to viciously attack the camp's refugees on April 30, 1871. The raiders savagely beat and murdered somewhere between 85-144 Apache, the vast majority of whom were either women or children.

Because the massacre took place away from the camp and lasted a mere 30 minutes, troops at Camp Grant could not hear what was going on, nor get there in time. Tucsonians considered the massacre a victory, and despite a federal indictment, no one was ever found guilty or convicted. Today, it still stands as the single biggest loss of life in Arizona's history.

Arkansas: The Elaine Massacre (1919)

Following the end of World War I, racial violence broke out all over the U.S. in the "Red Summer" of 1919. Bloodshed overwhelmed the nation, as riots in several cities resulted in lynchings and general mayhem over the Black labor movement — largely Black veterans returning from the war — demanding jobs and better opportunities. Racial prejudices and fears ran rampant among white citizens, who were also concerned Black workers' appeals were rooted in communism.

In Elaine, Arkansas, Black sharecroppers had met on September 30, 1919, to discuss wage and working improvements, but this upset the white owners of the plantations they worked on, leading to a shootout killing one white man and wounding another. The next day, on October 1, a white mob of as many as 1,000 strong came to Elaine and started destroying the town and wantonly murdering Black citizens. Falsely characterizing the Black labor movement as an uprising and insurrection, the white supremacists began shooting and killing Black residents at a disturbing rate. The governor called in the army to quell the violence, but they only restored order after allegedly killing several Black citizens themselves.

The actual death toll is undetermined but is thought to range in the hundreds. In the aftermath, more than a hundred Black residents were charged for insurrection, with a dozen receiving death sentences (that were only later mitigated after lengthy and messy court proceedings). No white residents were prosecuted.

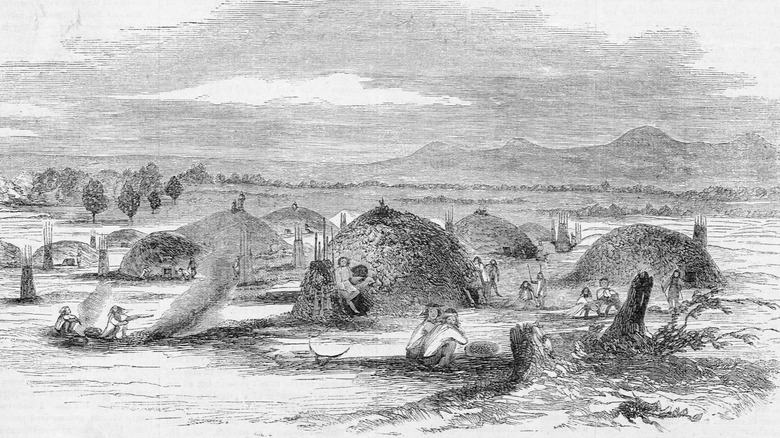

California: Yontocket Massacre (1853)

The early years of California's statehood were rife with violence between Native Americans and U.S. settlers. In northern California, hostilities between the Tolowa Dee-ni' and settlers started in 1851, when the Californians started to viciously push out the Tolowa from their ancestral homes along the Smith River.

With tensions already high, in 1853, a group of Tolowa near present-day Del Norte County allegedly killed a white prospector, prompting reprisals from other settlers against the tribe (via The Quartux Journal). After prospectors attacked and killed several of the Tolowa, the survivors fled to the Yontocket Rancheria, but they were hardly safe. Still intent on revenge, the white settlers attacked the tribe again at Yontocket.

The Tolowa were celebrating their annual Summer Nee-Dash festival when a company of Californians came in the early morning hours and slaughtered them. Displaying little humanity, the settlers massacred the entire settlement, setting the place on fire and shooting the Native Americans as they tried to escape. Several had their head chopped off and torched, and soon the Smith River was red with their blood.

The massacre continued for days and left an estimated 450-500 Tolowa dead, and it still stands as one of the worst massacre of Native Americans in U.S. history.

Colorado: Sand Creek Massacre (1864)

For thousands of years prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Cheyenne and Arapahoe lived peacefully in the area of what would become Colorado. Unfortunately, when settlers came in the 1800s things changed, eventually leading to hostilities by the 1860s.

In June 1864, local Native Americans were falsely linked to the murder of a family of settlers, outraging local whites. Immediately after, the Colorado Territorial Gov. John Evans began sanctioning vigilante violence against all Indigenous people but also offered them formal protection if they came to army-controlled forts. Roughly 700-750 Natives took Evans up on his offer and made their way to Sand Creek near Fort Lyon, but they were tragically betrayed when a rogue colonel in the Colorado militia decided to slaughter them.

Over seven hours on November 29, 1864, the militia under the command of Col. John M. Chivington killed some 230 of the Cheyenne and Arapahoe who thought they were under army protection, and the dead included prominent chiefs, women, children, and the elderly. The killers did not take any prisoners and even used cannons to fire at the largely defenseless group. They then hunted down those who fled, later mutilating some of their bodies before robbing them.

In the aftermath, while Chivington was ultimately condemned for his actions, he received amnesty and was never charged for ordering the killings.

Connecticut: Mystic Massacre (1637)

Between 1636 and 1638, settlers in New England and the Pequot tribe were involved in a series of devastating raids on each other after a breakdown in Pequot-English trade relations.

The worst of the raids occurred on May 26, 1637, in what is now Mystic, Connecticut. The English and their Narragansett and Mohegan allies attacked a large Pequot village, killing an estimated 500-700 villagers. The massacre was incredibly vicious, as the attackers hit the Pequot when they were still asleep, burning their wigwams, and engulfing the camp. If they weren't burned to death, many Pequot were shot or bayoneted. Most of those killed were non-combatants like women and children.

The massacre led to the downfall of the Pequot in the area and helped inform policy regarding Native American relations in the colonies and later the U.S., including assimilation and removal.

Delaware: Fort Zwaanendael Massacre (1632)

Located in present-day Lewes, Delaware, Dutch settlers first established Fort Zwaanendael in 1631 as part of their earliest expansion into the New World. The Dutch created Zwaanendael for whaling and agricultural production, and it was part of the larger New Netherland colony. However, the land was already inhabited by the Lenni Lenape (later Delaware), and things soon turned fatal between the two groups.

At some point in 1632, the Lenni Lenape killed 28 of the Dutch settlers at Zwaanendael in a terrible massacre. According to a contemporary report (via Delaware Historical and Cultural Affairs), events were set in motion after one of the Lenape chiefs, meaning no harm, made a tobacco pipe from an artifact featuring the Dutch coat of arms. This prompted members of the tribe to kill the chief and present his scalp to the settlers in atonement and appeasement. The Dutch, however, rejected the token and the act but also allowed those responsible to walk away. In retaliation for his death, the chief's friends murdered the Dutch settlers and torched Zwaanendael, destroying the settlement

Their bodies were found December 1632 by Dutch colonists who were returning with supplies from Europe. The returnees were able to ascertain what had happened from a local, who gave them the gruesome details of the dispute and attack.

Florida: Ocoee Massacre (1923)

In the early 20th century, Black Americans throughout the country were struggling to exercise their right to vote in the face of racist Jim Crow laws, which aimed to restrict them at every turn. Mose Norman, a successful orange farmer in Ocoee Florida, was one of those Black Americans attempting to vote in the elections when things turned especially violent on November 2, 1920.

Norman was turned away twice, the second time angering a mob of white supremacists, who followed him to a friend's house and incited a shootout. This set off a wave of terror and violence in town instigated by the mob, many of whom were members of the Ku Klux Klan. It's unknown exactly how many died at Ocoee, but sources place the number between 30 and 80 Black residents who died due to the mob violence — and countless more lost everything in the ensuing fire.

In the following years, the Black population in Ocoee plummeted to virtually non-existent due to the fear of renewed bloodshed and became known as a "sundown town" — essentially a place where Black people weren't welcome and could be endangered after dark. It took them more than 60 years to move back and a century for the massacre to be recognized and acknowledged as an important part of Florida history, including a requirement to be taught in local schools.

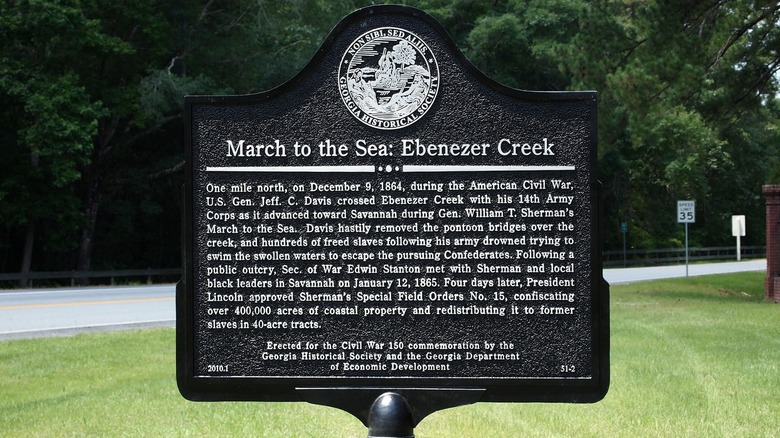

Georgia: Ebenezer Creek Massacre (1864)

During the Civil War, as the Union Army was making its way through Georgia and liberating the state, they often picked up Black refugees, like women, children, and the elderly, who sought the army's aid.

Union Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis did not like spending provisions on the formerly enslaved, known as Contrabands, also felt that they slowed up his marches. So when the Union reached Ebenezer Creek on December 8, 1864, Davis saw his opportunity to rid himself of the refugees. His troops hastily constructed a pontoon bridge to cross and were to safety by early the next morning, but Davis purposefully lied to the Contrabands and told them to wait until the end before crossing. Seizing the moment, he destroyed the bridge after his troops reached the other side, leaving the Contrabands stranded. When the Confederates came they began shooting at the refugees, and hundreds ran into the river in vain attempt to cross, with countless of them either drowning or being stampeded. Those who remained on shore were either shot or stabbed to death or were re-enslaved by the Confederate army.

While there is no official death toll, it's thought that hundreds and potentially thousands may have died that day. In disgust, it was Davis' own troops who turned him in, though he never was officially reprimanded.

[Image by Brendanghs via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Hawaii: Hanapepe Massacre (1924)

In the early 20th century, Filipino laborers in Hawaii found themselves working under incredibly tough conditions. Working brutal jobs for little pay, they created a labor union to fight for better treatment — and in 1924, they went on strike in Hanapepe on the island of Kauai (via Honolulu Magazine).

However, there was a split in the Filipino community on Kauai, and while the Visayan Filipinos went on strike the Ilocano Filipinos largely did not. Tensions increased when a group of Visayan strikers attacked and kidnapped a pair of young Ilocanos who were not striking. The police came to free the hostages on September 9, but when the strikers/kidnappers began chasing the police with knives things turned deadly. The police began open firing on the strikers, killing 16 of them while the rest desperately ducked for cover. The Filipinos were armed only with knives compared with the guns of the police, giving them little chance to defend themselves.

In the aftermath, the 16 dead strikers were buried in unmarked graves, and their families received just $5 each in condolences. The Filipino labor movement was left in shambles, and several of the strikers received jail sentences over the incident, while the police escaped punishment.

Idaho: Bear River Massacre (1863)

For thousands of years, the Shoshoni had been living peacefully in the area of present-day Idaho. However, in the 1800s, the U.S. began efforts to force them off their ancestral lands. In January 1863, things turned violent at the Bear River, after several Native Americans were suspected of killing and robbing more than a dozen miners and settlers.

With warrants for their arrests, several hundred infantry from the U.S. Army came upon a Shoshoni camp at Bear River on January 29. The Shoshoni chief tried to reach out peacefully to the army, but he was met by bullets instead. Displaying little humanity, the troops massacred an estimated 250-493 Shoshoni, who began fleeing in panic as the troops savagely cut them down. The entire area was covered in snow, making escape incredibly difficult, and some jumped into the Bear River in vain attempts to get away. Many of them ended up drowning or freezing to death, while others were shot by the troops as they floated away.

Even women and children were not safe from the massacre, and the troops looted and burned the village following the horrific violence. No soldiers ever faced punishment over the killings, and the few Shoshoni who survived were only given meager supplies to survive in the aftermath.

Illinois: East St. Louis Race Riot (1917)

By 1917, the Black population in East St. Louis, Illinois, had sharply increased, after many Black workers came to city to work in war production factories. This influx of Black residents angered some white residents in the area, who saw Black labor as a threat. In May and June, white mobs took to the streets to assault Black residents, and the National Guard had to quell the disorder.

The violence started again a month later on July 1, with shootouts between Black and white residents, including Black citizens killing two white police officers investigating the gun violence. The next day, white mobs came pouring into town and began beating, shooting, and lynching Black residents. Not even women and children were safe, and anywhere from 39 to more than 100 Black residents were murdered in the chaos.

The massacre was so horrific that Black families fled across the Mississippi River to neighboring St. Louis, Missouri, using makeshift rafts. In addition, many Black homes were torched and their residents murdered, causing more than 6,000 Black residents to flee the city over the violence. The Germans even tried to use the massacre as propaganda for the ongoing war.

It took a year and a special committee of the House of Representatives to indict several members of the police force.

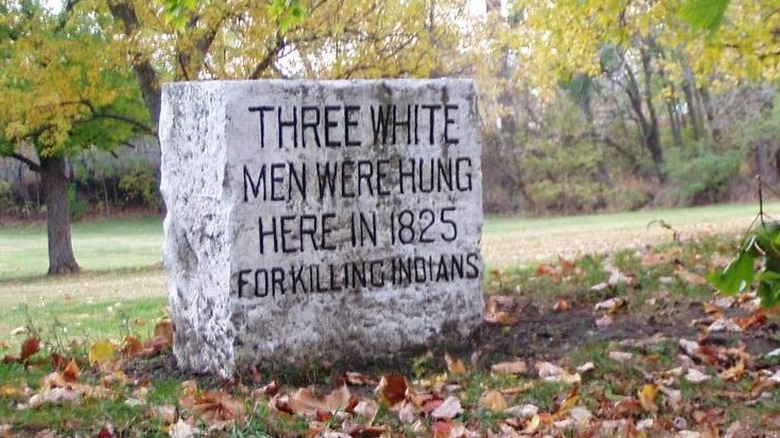

Indiana: Fall Creek Massacre (1824)

By 1818, the Native Seneca and Miami lost much of their territory in present-day Indiana via treaty. By the 1820s, even more of their homeland was under threat. Many of the new settlers held racist attitudes towards the Native Americans they were displacing, and when some suspected a group of Seneca and Miami of stealing their horses, they brutally slaughtered all nine of them at their camp.

It was March 22, 1824, near Fall Creek in Madison County, and the settlers apparently found footsteps connecting a local Native camp to their missing horses. After splitting up and killing the two adult males in the group, the settlers returned to murder the defenseless remaining three women and four children, with one of them claiming God sanctioned the murders.

After the massacre, the settlers looted the Natives' property before returning home, but word of the killings quickly spread. There were six men who participated in the killings, but only five were put on trial after one of them fled, and just four of them were convicted of murder. One of the men received a pardon due to his young age, but the other three were executed by hanging. It was one of the few instances of white settlers being punished for killing Native Americans and helped set a judicial precedent for the future.

Iowa: Spirit Lake Massacre (1857)

Throughout the 1850s, tensions between Wahpekute Dakota and settlers in Iowa grew over a series of violent incidents. White settlers killed or severely beat several Native Americans but escaped punishment, and the settlers later disarmed the Wahpekute and caused them to leave the area after suspecting them in a large robbery.

The Natives, starving and defenseless, began plundering various settler camps across the north, eventually arriving at Spirit Lake in March 1857. The Wahpekute were familiar with Spirit Lake, and they considered it extremely holy and a resting place for their gods. So, when the Wahpekute spotted a camp of settlers at the lake they considered it an afront, and they attacked.

First, they demanded food, but when they were not given enough they went around from cabin to cabin and began massacring the settlers. They shot some and smashed the heads of others, scalping many of them, and the 32 victims included defenseless women, children, and even infants. The Wahpekute then kidnapped four women, including Abbie Gardner (pictured above). They beat their captives and later killed two of them, though Gardner survived and later returned home.

The Dakota were never held responsible for their actions and remained in the area. The massacre was one of the many factors leading to the bloody Sioux Uprising a few years later, which would claim countless more Native and white lives.

Kansas: Lawrence Massacre (1863)

The Civil War was one of the most violent events in American history, and unfortunately, at times the carnage even spread to the civilian population. One of the worst instances took place in Lawrence, Kansas, when Confederate guerillas under Capt. William Quantrill attacked the town. Before and during the war, Kansas was known for strong abolitionist sentiment, and that combined with the recent death of several Confederate women at a nearby Union prison may have prompted Quantrill's raid.

Quantrill and 400 of his raiders attacked Lawrence on August 21, 1863, and killed 160-190 residents while destroying the town. The raiders specifically went after Black residents and shot dozens of them, and they burned several buildings to the ground. It's thought the raiders created more than $1 million in damages, and residents found themselves fleeing to cornfields or hiding in their cellars to escape the violence.

Following the Lawrence Massacre, Quantrill's legacy as one of the worst villains of the war was firmly cemented. As a result of the massacre, the Union ordered all residents in the area to relocate, reducing the potential for further incidents.

Kentucky: Long Run Massacre (1781)

In April 1780, a group consisting of several families of American settlers founded Painted Stone Station in present-day Shelby County, Kentucky. Unfortunately, they soon ran afoul of hostile Native Americans in the area, who were allied with the British during the ongoing Revolutionary War. After several months of raids on the station, by September 1781, the settlers were planning on leaving Painted Stone behind due to its isolation and vulnerability to continued attacks.

However, as the settlers were leaving with their supplies, a band of around 50 Miami Natives attacked them at Long Run Creek on September 13. The settlers had only one road to escape on, which left them very exposed, but they had planned for a potential Native attack. Unfortunately, the wagon train was completely disorganized and quickly split apart, making them easy prey. The Natives began slaughtering the disjointed wagon train, killing several women and children, and 60 pioneers in all. Many of the settlers fled and tried to escape, only to be hunted down and killed.

The next day, a group of 27 militia returned to the scene of the massacre, but the Miami attacked them again, killing another 17 men. In all, the Miami killed at least 77 settlers in just two days.

Louisiana: Opelousas Massacre (1868)

When Louisiana rejoined the Union following the Civil War, they had to enact a new constitution as part of their re-admittance procedure. When they did so in April 1868, it was pretty revolutionary for the state, and included giving Black residents citizenship, the right to vote, and banning segregation. New Black voters turned out in drives that election year and helped give the Republican party a strong foothold.

Yet, this upset white Democrats, who were worried about losing all of the political power they had acquired in the antebellum years. Local partisan newspapers were often used as tool to instigate violence, particularly by the Democrats.

After a young Republican editor published an inflammatory article on September 19 accusing Democrats of violent intimidation and espousing the moral superiority of his political party, white Democrats decided to retaliate in incredibly violent fashion. After first forcing a retraction from the paper, the white mobs began killing residents in the area over the course of two weeks, murdering somewhere between 200-300, most of them Black. They also went after white Republicans who they deemed responsible for the party's success, killing several of them and destroying houses, churches, and stores.

Following the massacre, the white mob was successful in removing Republican political power from the area, which had been shaping up to be a stronghold. Not a single vote was cast for Republican Ulysses S. Grant that November, and the Republican press wouldn't return for nearly a decade.

Maine: Norridgewock Massacre (1724)

The Wabanaki had been living in present-day Maine for centuries by the time of the arrival of the English in the 1600s, and by 1722, they were already fighting their third war against each other in just over 30 years. The war broke out after the British raided a Wabanaki settlement looking for a French Jesuit missionary, Father Sebastien Rale, who was providing the Native Americans with ammunition to use against the English.

After two years of trading blows, the English attacked the Wabanaki at Norridgewock on August 23, 1724, massacring 80 civilians. A group made up of colonists and a few of their Mohawk allies raided the Wabanaki village, attacking and then shooting them as they tried to flee (per the New England Quarterly). Several of the Natives reached their canoes on the Sandy River, but the attackers dragged them out of the canoes and beat them to death. Only about 50 of the Natives were able to escape, with the raiders killing the rest, including Father Rale who was at the camp.

The victims included women and children, many of whom were innocent civilians. After the massacre, many of the Natives were sent north to Canada, and the war ended the next year with a peace treaty.

Maryland: Pratt Street Massacre (1861)

Most people do not realize but the first bloodshed of the Civil War actually happened during a riot in Baltimore rather than on the battlefield. After the war broke out following the Battle of Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln began beefing up the Union Army, and just a week later on April 19, 1861, there were already troops in Baltimore, Maryland — a border state with heavy secessionist activity.

The troops were actually on their way to the capital in Washington, D.C., but were met by a secessionist mob while changing trains in Baltimore. The mob began throwing bricks and rocks at the troops in an effort to prevent them from reaching Washington. In a panic, several of the troops were given orders to fire into the crowd of rioters, eventually killing 12 of them. The rioters also fired back at the troops, killing four and injuring several others.

The troops were finally able to escape the chaos and get onto their train, but only with the help of the Baltimore police, and the massacre stunned the city. As a result of the riot and bloodshed, Baltimore was soon under martial law and federal occupation, which would last through the end of the war.

Massachusetts: Peskeompskut Massacre (1676)

One of the most significant wars of the colonial era was King Philip's War in the late 17th century. Native Americans under the leadership of Metacom (King Philip) fought against English colonists over land and authority.

About a year into the war, on May 19, 1676, at the Battle of Turners' Falls — or Peskeompskut Massacre as it's more aptly known — 150 English colonists attacked a sleeping camp of Natives located at present-day Gill, Massachusetts. The Natives were camped at the Connecticut River for their annual fish gathering when colonists began assaulting them. The Natives were largely made up of the Nipmuc, Narragansett, Wampanoag, and Pacumtuc tribes, and the victims included the elderly as well as women and young children. The brutally efficient killing took only an hour, and it's thought there were around 200 Native victims from the massacre.

The Natives were able to exact some revenge, killing 38 of the militiamen during their retreat. Still, the massacre led to the Natives' loss in the war, as well as to the subjugation or execution of many of those who survived Peskeompskut.

[Image by Denimadept via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

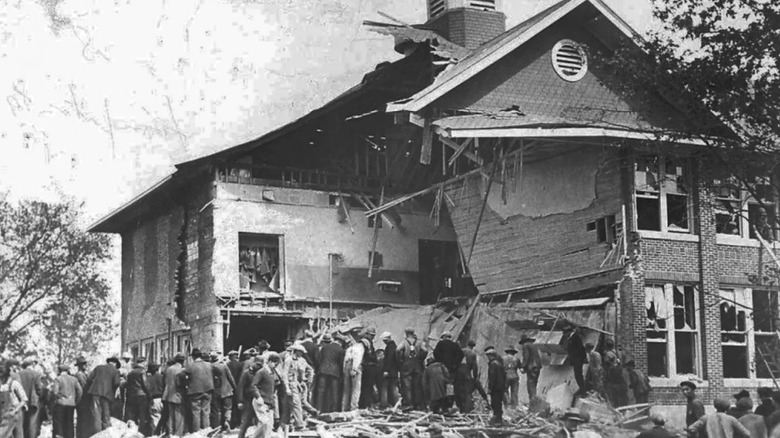

Michigan: Bath School Disaster (1927)

The Michigan Bath School Disaster on May 18, 1927, is still considered the worst school massacre in American history. The incident happened in the Michigan Bath Township at the newly opened Bath Consolidated School. Local tax money was being used to pay for the school's creation and upkeep, which upset resident Andrew Kehoe. Kehoe resented paying for the school and did whatever he could to route funds away, including becoming the school board's treasurer to deny the school of funds — but after years of animosity something snapped.

The day before the disaster, Kehoe murdered his wife at their farm, which he blew up the next day. After destroying his farm, he blew up the school with explosives he planted months before, killing 36 children and two teachers and desroying half the school in the blast. But Kehoe was still not done. After the timed explosives went off, he then drove to the school a few minutes later and detonated a second bomb, killing another five, including himself. More unexploded devices were found in other areas of the school, indicating Kehoe's plan was likely razing the entire facility with everyone inside.

Afterwards, the school was immediately demolished and another erected on the same site.

Minnesota: Red Lake Shootings (2005)

On March 21 2005, teenager Jeffrey Weise decided to go on a murderous spree on the Red Lake Indian Reservation in northern Minnesota, where he shot and killed seven people at Red Lake High School, including five students, a teacher, and a security guard. These weren't his only victims, as Weise had also murdered his grandfather and his grandfather's girlfriend at home, prior to setting off for the school.

A motive for the slayings was never established, although Weise was known to be interested in school shootings, and violent drawings were found in his notebooks. It was also discovered he had pro-Nazi leanings. In the end, the rampage left 10 people dead, including Weise who died by suicide, and several more injured. The shooting still remains Minnesota's deadliest mass shooting.

Mississippi: Vicksburg Massacre (1874)

The election of Peter Crosby as the first Black sheriff in Vicksburg history should have been a time of joy and progress. Unfortunately, white supremacists turned it into bloodshed and violence. Crosby was a former laborer in the U.S. Army who had served during the Civil War, and he won election to become Vicksburg's sheriff in November 1873.

However, barely in office a year, a huge mob of white residents forced Crosby's resignation, falsely accusing him of financial improprieties as sheriff, and ran him out of town. In his defense, a group of unarmed Black residents marched on the courthouse on December 7, 1874, where things quickly turned violent — the white mob began firing upon them, despite that most had turned around.

Some 600 white men killed as many as 300 Black Vicksburg residents, and federal troops had to be called in to calm the chaos and reinstate Crosby as sheriff. However, he'd again be subjected to violence when one of his white deputies shot him in the head seven months after the massacre, permanently injuring Crosby.

Missouri: Centralia Massacre (1864)

It's not easy to get a nickname like Confederate Capt. William "Bloody Bill" Anderson's, but that doesn't mean it was not rightfully deserved. Known as one of the biggest villains of the entire Civil War, Anderson owes a good deal of his nickname to a September 27, 1864, incident in Centralia, Missouri. At the time, much of Missouri — which was a border state during the war — was being torn apart by Union and Confederate guerillas, some of whom were under the command of Anderson (pictured above).

During the Centralia raid and massacre, Anderson and his guerillas tore apart the town as the residents hid in terror — but that wasn't the worst of it. After destroying the town, Anderson's guerillas set their sights on a train leaving from St. Louis, and onboard were some Union soldiers on leave. Defying all rules of combat and morality, the Confederates stripped and then executed all 24 of the Union soldiers. The guerillas even scalped some of the dead bodies before burning the train, leaving the passengers stranded, horrified, and without protection.

It was a terrible massacre and a clear war crime, though no one was ever prosecuted. The Union army retaliated by killing civilians in Rocheport suspected of harboring Confederate guerillas and hunting down Anderson, who died almost exactly two months later at Union hands.

Montana: Marias Massacre (1870)

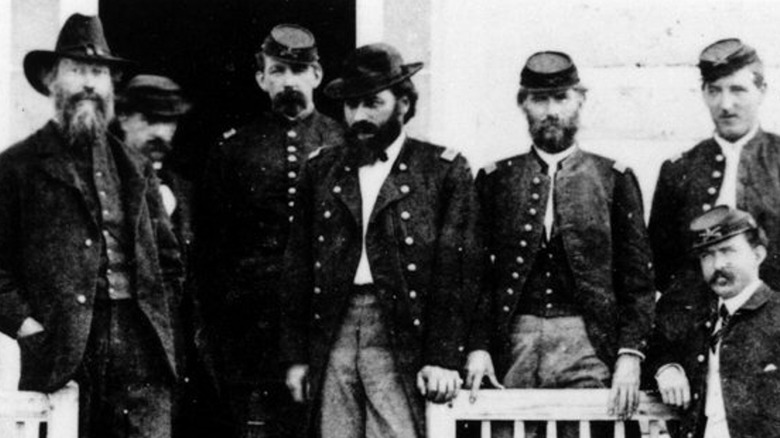

Even in terms of Native American massacres, the Marias or Baker Massacre stands out for its stunning inhumanity. The massacre was led by U.S. Army Maj. Eugene Baker (above center), who was dead set on killing Native Piegan Blackfeet by any means necessary.

In the fall of 1869, a dispute between a Blackfoot named Owl Child and a Montana rancher left the rancher and his son dead. Outraged, local Montanans demanded retribution, so U.S. Army troops were called to seek out Owl Child and those who sheltered him. On January 23, 1870, the troops came upon a Native American camp on the Marias River and readied an attack. However, they soon realized it was peaceful band of Blackfeet, not associated with Owl Child. But that didn't matter to Baker, who ordered his soldiers to attack indiscriminately and

light the entire camp on fire.

Baker and his men killed 177 Blackfeet at the camp, including 50 children. They also imprisoned an additional 140 but abandoned them without provisions soon after learning they had smallpox, leading to many more deaths. While the incident incurred massive public outrage, Baker never faced any punishment.

Nebraska: Fort Robinson Massacre (1879)

In 1877, after living for centuries in Wyoming, many Cheyenne under Chief Dull Knife were forced to leave the area and move to a reservation by U.S. troops. By then, Dull Knife was already weary of the U.S. after many years of battles but had little choice but to accede after losing a war against them the year prior.

However, the reservation they were forced upon was unlivable for the Cheyenne. It was nowhere near their homelands in Wyoming, and they found it difficult to survive. After a year, many of the Cheyenne left and tried to go home, getting as far as Fort Robinson in Nebraska. At Robinson, the army tried to force the Cheyenne to return to the reservation, but Dull Knife and 100 of the Cheyenne instead escaped again in early-1879.

Unfortunately, troops from Robinson caught up with them on January 22. Short of food and without shelter in the cold winter, the Native Americans were almost defenseless outside of a few hidden guns. The troops killed 64 Cheyenne in the massacre, though Dull Knife was not one of them, and the army only lost 11 in the lopsided fight. Those who weren't killed were imprisoned back at Robinson, before again being forced to live on another reservation, though one that was at least closer to their homeland.

Nevada: Las Vegas Shooting (2017)

In October 2017, Las Vegas was playing host to the Route 91 Harvest music festival, which took place mostly outdoors right on the strip. However, what was supposed to be a night of joy and celebration soon turned into a horrible nightmare, when gunman Stephen Paddock began firing into the crowd from his hotel room on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay on October 1, the event's final night.

At first, people didn't know what was going on and some mistook the shots for fireworks, but within a few seconds it was clear something far more sinister was happening. The entire event was engulfed in chaos as people began fleeing the scene, and attendees started falling left and right with gunshot wounds. In the end, Paddock killed 58 people in less than 10 minutes, firing more than 1,100 rounds out of high-powered guns. Paddock himself died by suicide, and it took authorities more than an hour to finally gain entrance to his room, where he was already deceased.

The massacre outraged and shocked the nation and is the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S history.

New Hampshire: Cocheco Massacre (1689)

In the 1670s, relations between the Native Penacook and English settlers at the Cocheco settlement in present-day Dover, New Hampshire, started to deteriorate after decades of peace. The problems began when the English kidnapped several hundred of the Penacook's Native American allies in 1676, eventually killing and enslaving many of them. When a new militant chief took control of the Penacook a few years later, hostilities between the groups greatly increased, and they never forgot the betrayal.

Over a decade later on June 27, 1689, the Penacook exacted their revenge on the English. They attacked the garrisons of five different settlers at Cocheco near downtown Dover, killing 23 and capturing 29 in a horrible bloody affair. The Penacook were able to gain entrance to the garrisons under the guise of seeking peaceful refuge. Yet, once inside, they opened the gates and allowed their friends to enter, and soon they started killing, looting, and burning the garrisons.

During the massacre, the Penacook mutilated and cut apart the leader of Cocheco, Maj. Richard Walderne, while butchering several others. Those who were not murdered were taken prisoner, including an infant, who was subsequently taken to Canada with the others and raised in Quebec by nuns.

New Jersey: Baylor Massacre (1778)

The American Revolution was one of the most important events in the history of New Jersey, but the Baylor Massacre is one of its saddest and deadliest legacies. The massacre was an attack by British troops against 120 Dragoons from the Continental Army, who were near what is now River Vale Road in New Jersey.

The Dragoons had been stationed in the area since the Summer of 1778 and were protecting New York City from invasion. However, the British under Maj. Gen. Charles Grey discovered their camp and attacked them while they were sleeping on September 28, 1778. Grey was known for his brutality in combat, and the inadequate security of the Dragoons made them sitting ducks. In the early morning hours, hundreds of British troops viciously attacked the sleeping Dragoons, bayoneting, clubbing, and shooting many of them to death.

Both the American officers in charge were fatally injured, though one of them didn't die until a few years later. In the aftermath, at least 15 Americans lay dead and several more were severely injured or taken prisoner.

New Mexico: Acoma Massacre (1599)

Long before the Americans came to area of the Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico, the Native Acoma people called the land home. They had a large settlement on the Acoma Pueblo in the valley since at least the 1200s, but they ran into trouble in 1595 with the arrival Spanish conquistadors who came to colonize the area (per Brigham Young University). One of the conquistadors, Juan de Oñate, declared the area of the Acoma Pueblo to be part of New Spain.

However, when Oñate's nephew Juan de Zaldívar came to inform the Acoma of their new leaders and gain their recognition, things turned violent. The Acoma killed Zaldívar and his men after the conquistadors tried to take provisions by force, prompting Oñate to come to the pueblo himself on January 21, 1599. When Oñate came, he and his men blasted the Acoma apart with rifles and cannons, killing as many as 800 in the brutal two-day melee.

The Spanish burned the Acoma pueblo to a crisp, and then mutilated many of those they didn't kill by taking the right foot of any living Acoma aged 25 or older as punishment. In addition, they also sold the surviving women and children into slavery. It was potentially the worst Native American massacre to ever take place in North American history and led to the decline of the Acoma people in the area.

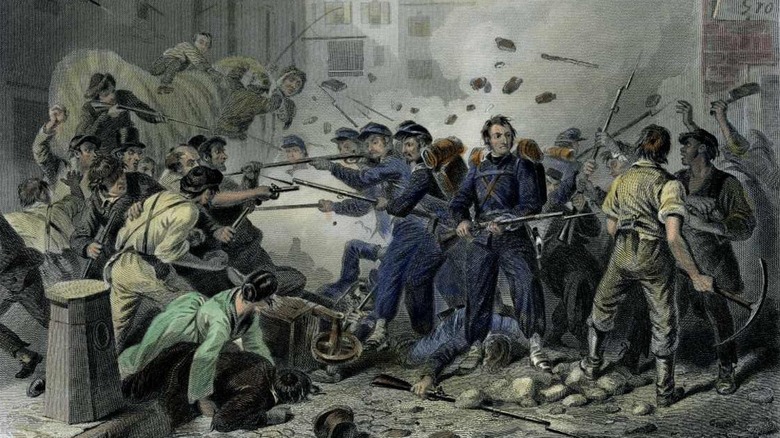

New York: New York City Draft Riots (1863)

During the Civil War, New York City had a surprising amount of secessionist sympathies, as the South's cotton had been an important part of New York's powerful economy. Many of the city's politicians were anti-war, and a large contingent of the working-class had pro-slavery sympathies as they feared the competition of free Black labor in the city.

When President Abraham Lincoln announced a new conscription law in 1863, it was immediately met with derision and hostility by many of the working class in New York. Already contentious towards the war, they were upset that the bill allowed the wealthy to buy their way out of serving for the hefty fee of $300, and that Black residents were not eligible for conscription (as they were not legally considered citizens).

After the first draft lottery on July 11, 1863, the streets erupted two days later on July 13 with mayhem and extreme violence. The mainly white mobs targeted government buildings as well as the military in the city, but soon they began seeking out Black citizens and white abolitionists. Estimates vary widely, but it's thought anywhere from 119 to as many as 1,200 lost their lives in the massacre.

Finally, federal troops fresh from Gettysburg put down the riots days later, but not before there was incredible destruction, including the loss of thousands of Black residents' homes, which led to a diminished Black community in the city for years.

North Carolina: Wilmington Massacre (1898)

In Wilmington, North Carolina, Black residents gained political power for the first time during Reconstruction, which angered racist whites. However, by the late-1890s, Reconstruction was long over and the racist Jim Crow era was underway. In Wilmington, white supremacists were determined to take back the legislature from Black Republicans during the 1898 elections. During the election season, white Democrats ran a racist campaign and intimidated Black residents into not voting, before further rigging the election with faulty vote counting on the day of.

After the election, which the Democrats handily won, a 1,000-strong white mob created a "White Declaration of Independence." It unconstitutionally called for white rule of Wilmington, and on the morning of November 10, 1898, the mob carried out a violent coup. First, the white mob burned down a Black-owned newspaper, before turning their sights on the Black community at-large.

The mob started indiscriminately murdering Black citizens in the city, using powerful weapons including rapid-fire machine guns. The governor called in the state militia, but they joined in the massacre too, killing at least 25. In all, historians estimate that as many as 250 residents died, most of them Black.

After the massacre, the white mob forced Republican politicians and Black police officers to resign and leave the city, and thousands more Black residents joined them fearing their safety. The city's Black population plummeted in the years after, and it took decades before the city had any Black representation in elected office.

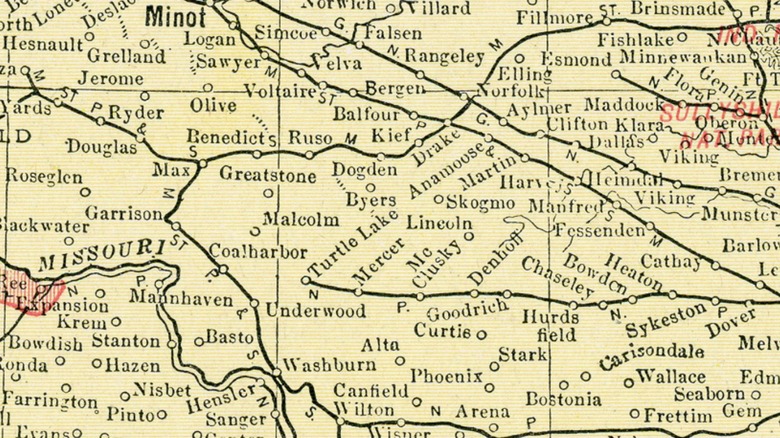

North Dakota: The Wolf Family Massacre (1922)

Being a farmer in 1920s North Dakota could be dangerous, just not always in the way you might think. In April 22, 1922, North Dakota farmers Jacob Wolf and Henry Layer had gotten into a dispute after Layer thought that one of Wolf's dogs injured his cow. But what started as an argument soon turned into a bloodletting.

According to Layer's confession, the killings started after Layer confronted Wolf over his dog. After Wolf began loading his shotgun the two got into a struggle, leading to the death of Wolf's wife and their hired hand when the gun went off. After their deaths, Layer tracked down and mercilessly killed Wolf and five of his daughters, including hacking one of the girls to death, leaving only an infant to survive because he apparently did not notice her. After the murders, Layer covered the bodies and fled, but he was caught returning the next day to the scene of the crime by the sheriff, which partly led to his eventual capture.

Layer would admit to the murders, claiming the first ones were accidental but that he went into a blind rage afterwards. After an extremely quick arrest and confession, he was transferred to prison to begin serving his life sentence, and he died five years in.

Ohio: Gnadenhutten Massacre (1782)

Moravian missionaries were some of the earliest Europeans to come to Gnadenhutten, Ohio, in the years just prior to the Revolutionary War. They enjoyed a peaceful relationship with the Delaware and Mohican tribes, even converting many of the Native Americans to Christianity. They remained allies while the Revolutionary War broke out but were later banished from the area in 1781 by the British, who suspected them of conspiring with the colonists. By early 1782, a large group of the Native Americans attempted to return to the area in search of food, but this time they ran afoul of the colonists instead of the British — and the colonists treated them much worse.

At the time, there had been attacks on white settlers nearby, so the returning Native Americans were mistakenly believed to be the culprits. The colonial militia rounded them up under the guise of friendship, before disarming and then killing them. They murdered 90 of the Natives, children among them, and scalped at least two in a spectacular display of violence.

Oklahoma: Oklahoma City Bombing (1995)

Timothy McVeigh was a U.S. Army veteran and anti-government extremist, who was upset over the government's actions during the recent Ruby Ridge and Waco massacres, which had resulted in the deaths of numerous civilians at the hands of the government. In retaliation, on the two-year anniversary of Waco, he blew up the Alfred P. Murrah Building in downtown Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995, using a homemade bomb detonated from inside a rental truck. In addition to the 168 dead — 19 of whom were children at a daycare inside the building — there were another 650 injured. In the surrounding area, 300 buildings were also damaged from the blast, and it was a shocking level of carnage that angered the nation.

McVeigh was caught a short time later on an unrelated traffic violation but was soon discovered to be the perpetrator. He was executed in 2001, and a memorial stands at the site of the former Murrah Building today marking the worst massacre in the state's history.

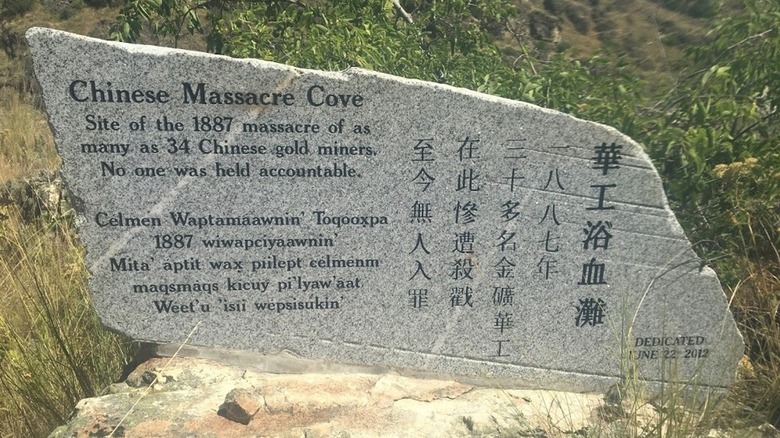

Oregon: Hells Canyon Massacre (1887)

In the 1880s, Chinese immigrants in the U.S. faced severe discrimination from many white Americans. In addition to legislation like the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act that restricted immigration, they also faced bigotry from fellow workers who resented that they were willing to be paid less. In May 1887, several Chinese miners from Idaho Territory made their way to Hells Canyon in Oregon Territory, hoping to mine in isolation away from the discrimination and harassment they had been facing.

However, while the miners were trying to peacefully work, they were attacked by a group of seven white men from Wallowa County, Oregon. The white men killed all 31-34 of the miners between May 27-28, including beating one to death with a rock, before robbing the camp clean. Due to the remoteness of the area, their mutilated bodies were not discovered for weeks until they finally washed up ashore in Idaho.

Three of the alleged murderers escaped town shortly after being indicted for murder the next year, but three others were later found not guilty, likely due to racial bias from the jury. It wasn't until 2005 that the crime was even officially recognized, and a memorial commemorating the massacre was erected in 2012.

[Image by kesterallen via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Pennsylvania: Wyoming Massacre (1778)

The Revolutionary War had its fair share of violent and gruesome episodes, but few stand out like the Wyoming Massacre on July 3, 1778. The massacre began as the Battle of Wyoming, which pitted Connecticut troops from the Continental Army against a combined, superior force of British, Native Americans, and loyalist Pennsylvanian colonists.

The British-led force was trying to push into the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania, which the Continentals were tasked with defending. The Continentals went on the offensive to attack the British-Native-Loyalist-force but ran into a deadly trap. The British hid in the woods near their fort as the Continentals approached, but as soon as they got near the British Native allies pounced. In the chaos, the Continentals began to retreat to their base at Forty Fort, but most of them never made it.

The battle quickly devolved into a brutal massacre, as the invading forces started indiscriminately killing not just the American troops but also women and children sheltering at Forty Fort. Many of the retreating troops were cutdown in a deadly crossfire from the British and loyalists, and barely 60 of the 386-strong Continental force survived. In all, the British and their allies killed 360 American settlers and militia, torturing and then scalping 227. Following the massacre, the area was largely barren of white settlement for years, until the Continental Army took it back at the end of the war.

Rhode Island: Great Swamp Massacre (1675)

While largely forgotten today, King Philip's War in the late-17th century saw the Puritan colonists of New England take on a Native American alliance consisting of the Narragansett, Wampanoag, Nipmuck, and Pocumtuck. The Natives were led by the Wampanoag Metacom (King Philip), who resented the encroachment of the English onto Indigenous land, and on December 19, 1675, war broke out between the Puritans and Natives over land disputes.

The Narragansett had a fort at the Great Swamp in present-day West Kingston, Rhode Island, which served as their home base. However, the Puritans discovered its location after a Native deserter showed them, and they attacked when Metacom and his allies were inside. The Puritans quickly overwhelmed the Native defenders, and what started as a battle deteriorated into a brutal massacre. Those who were not shot were burned to death, and victims included not just Native warriors, but also women, children, and the elderly.

The bloodshed was so severe there isn't an accurate count of how many Narragansett died, but it's believed to be anywhere from 300-600. Prior to the massacre, the Narragansett were largely neutral in the war, so it was a pre-emptive English strike to take them out before they could join against them. However, the Narragansett retaliated for the massacre by joining the Native American alliance and helping burn New England the following spring.

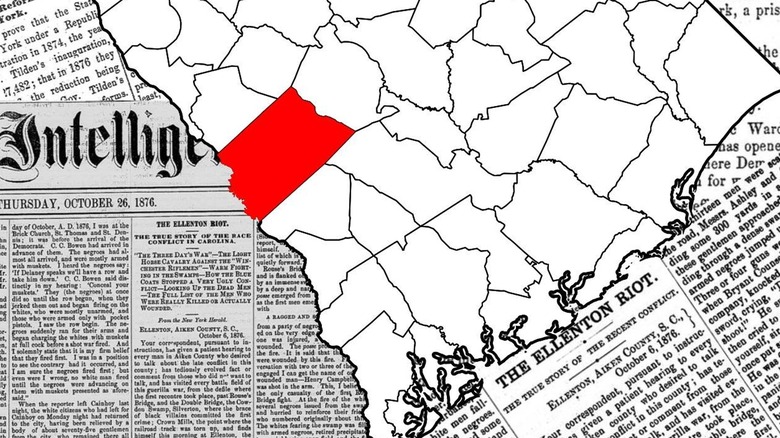

South Carolina: Ellenton Massacre (1876)

Following the end of the Civil War, the Reconstruction era was supposed to rectify the wrongs of slavery and put Black citizens on an equal footing with their white counterparts. However, white supremacists throughout the South fought back against these new progressive changes, and massacres like in Ellenton, South Carolina, in September 1876, were endemic of the violence they used to regain control.

Leading up to the November election, white supremacists in Ellenton had been spreading lies about Black residents in an effort to blunt the Republican turnout, falsely accusing them of assaulting a white woman. When a warrant was drawn up for the alleged perpetrators, white mobs took it upon themselves to look for them, and they ended up committing mass violence against the Black community.

The mobs, which styled themselves as "gun clubs" and were armed, killed anywhere from 30 to more than 100 Black residents between September 16-19. They targeted their victims at home and at work, and not even houses of worship were off limits for the depraved murderers. It was not until the army came that the mobs relented. Tragically, no one was ever held responsible for any of the murders during the massacre, and Reconstruction officially ended following the 1876 elections, inaugurating a reign of white supremacy in the South.

South Dakota: Wounded Knee (1890)

Perhaps no incidents are as infamous in Native American history as the tragic Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29, 1890. The massacre happened just after the murder of major Lakota Sioux Chief Sitting Bull by U.S. Army troops, who was wrongly linked with the burgeoning Ghost Dancer movement. The U.S. Army was worried about the Ghost Dancers because they advocated for renouncing the ways of the white man, which the U.S. government was trying to force upon the Lakota.

After Sitting Bull's death, a large contingent of his people went to join other Lakota at Pine Ridge in South Dakota, but before they could make it the army intercepted them and started to disarm them of their guns. During the seizure, one of the Lakota's weapons went off while another was performing the Ghost Dance, triggering a mass of chaos and violence.

In the deluge of confusion, the army began wantonly massacring the Native population. Without their weapons the Lakota were essentially defenseless, and they put up little resistance. The army used several machine guns perched above the camp to fire at the fleeing Natives, killing an estimated 250-300 of them, mostly women and children.

In the aftermath, the army portrayed the incident as a heroic fight against savages, and many of the attackers were even awarded Medals of Honor. Later, the truth emerged, but the massacre devastated the Lakota and largely ended the Ghost Dance movement.

Tennessee: Fort Pillow Massacre (1864)

During the Civil War, Fort Pillow was first a Confederate military installation, only for it to come under Union hands in 1862. Yet, by April 12, 1864, the Confederates under Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest were ready to retake Pillow, and they did so decisively.

Fifteen-hundred Confederates under Forrest attacked the fort, and they completely overwhelmed the outnumbered Union defenders in the Battle of Fort Pillow. However, after the initial battle, things degenerated into a massacre of the surviving soldiers. Instead of taking in the surviving Union soldiers as prisoners of war, the Confederates slaughtered them in a heinous bloodbath. Most disturbing is that they seemed to target Black Union soldiers in the fort, and they shot some as they jumped into the nearby river trying to escape. Many of the victims who were wounded in the initial battle were later killed during the subsequent massacre.

In all, the Confederates killed 300 Union men in the battle and massacre — 200 of the dead were Black soldiers. Despite a federal investigation, Forrest and the Confederates never admitted to any wrongdoing, and they never faced any punishment.

Texas: Waco Siege (1993)

In early 1993, federal agents in Texas had their eyes on the Waco compound of the Branch Davidians. The Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms bureau (ATF) became suspicious of leader David Koresh after allegations of child abuse and gun-running. On February 28, the ATF raided the compound,

setting off a 51-day battle between the religious group and government forces.

The February raid proved extremely violent, leading to the deaths of 10 people. Over the course of the next several weeks, negotiations stalled as Koresh kept his compound on lockdown with many of his followers inside. On April 19, the ATF hit the compound again, the events of which are still highly disputed. What is known is that the ATF sprayed large amounts of tear gas into the compound, prompting the Branch Davidians to respond with gunshots and later set the compound on fire. The assault lasted more than five hours and ended up taking the lives of another 75 Branch Davidians, several of whom had been shot to death. One-third of the dead were children, and Koresh himself lost his life.

The ATF claimed they never fired any guns during the incident, and they were officially exonerated after an official investigation. However, their actions that led to so many deaths were widely criticized as an abuse of authority. The Waco Siege since became a rallying cry for anti-government extremists, including the Oklahoma City Bomber Timothy McVeigh.

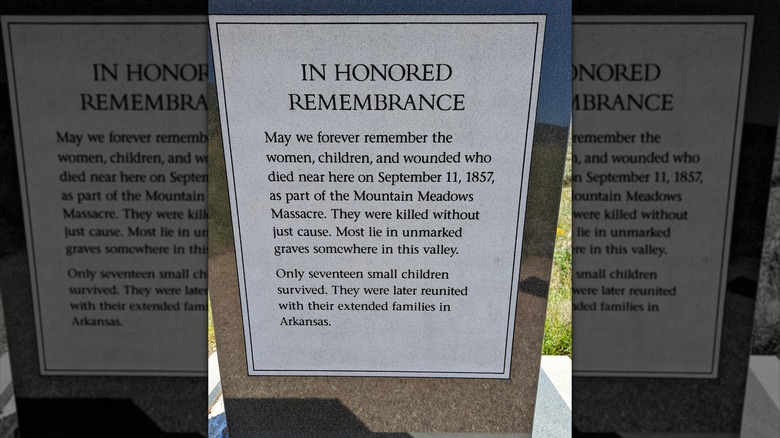

Utah: Mountain Meadow Massacre (1857)

Since 1850, Mormon authorities under Gov. Brigham Young had been in control of Utah. But by 1857, Young's theocratic ways of running the territory began to draw the ire of federal officials, who threatened to send troops to takeover the government.

In response, Young decided to show the federal government the extent of his authority and control in Utah by sanctioning attacks on wagon trains traveling through the area on their way to California. One of the wagon trains passing through was the Baker-Fancher party from Arkansas, who were attacked on September 7, 1857, by a group consisting of Paiute Native Americans and Mormon militia disguised in Native garb to look like them.

After five days of assaults, Mormon militia leader John Lee feared the role of white Mormons had been discovered, so he lured the settlers out with a false white flag but then proceeded to massacre them. The Mormon and Paiute shot and slashed 120 settlers to death, killing anyone over 7 years old while kidnapping more than a dozen children to raise as their own.

While Young's role in the massacre is disputed, Lee was later sentenced to death and executed by firing squad in 1877 for his actions.

Vermont: Westminster Massacre (1775)

In the 1770s, as the Revolutionary War was breaking out, disputes over land in what is now Westminster, Vermont, turned incredibly violent and deadly. The residents of Westminster were part of the New York Colony but considered themselves New Englanders at heart (via the Eagle Times). In 1775, several settlers in the area were having their homes foreclosed on by the New York court system, and they demanded the local judge close the courts hearing their foreclosure cases.

However, the judge called British Tory reinforcements to keep the courts open, so the residents responded by showing up to the courthouse armed with wooden staves. After occupying the courthouse overnight, the Tories showed up on March 13 and started firing into the crowd of colonists. Daniel Houghton and William French both died of gunshot wounds sustained at the courthouse.

The town was outraged over the incident, and a Patriot militia arrived to restore order soon after. The militia then arrested the Tories and sent them away to Massachusetts, where they were ultimately exonerated.

Virginia: Saltville Massacre (1864)

The Battle of Saltville on October 2, 1864, was a terrible fight that resulted in hundreds of casualties, mainly on the Union side. The Union tried to take the Confederate camp at Saltville, Virginia, but they ran into an iron wall and lost the battle decisively. What happened next turned the fight from a battle into a horrible massacre.

After the initial battle was over, many injured Union troops remained on the battlefield, slowly dying from their injuries. Tragically, instead of aiding them, Confederates killed many of the injured Black soldiers as they laid helpless and defenseless the next day. The Confederates deliberately targeted and singled out Black troops on the battlefield, leaving none of them as POWs like their white counterparts. Some of the Black troops were recuperating in field hospitals when Confederate soldiers rounded them up and took them to be executed.

Obviously, these were clear war crimes, and it's thought that the Confederates murdered 45-50 Black Union soldiers. After the war, the Confederate leader responsible for the massacre, Champ Ferguson, was hanged for his actions.

Washington: Wah Mee Massacre (1983)

Just before midnight on February 18, 1983, patrons at the Wah Mee gambling club in Seattle were enjoying drinks and the usual debauchery when three criminals took it over and started tying people up and robbing them. However, the criminals didn't stop there. Before leaving, the assailants shot those they robbed, killing 13. In the aftermath, one victim managed to survive and get help from people trying to get in from the locked security doors, who then called police. The victims ranged in age from 47 to 68-years-old, and the community was devastated over their deaths.

Now known as the Wah Mee Massacre, the deadly shooting was a shocking display of brutality. Eventually, the three murderers were brought to justice when the only surviving victim testified against them in court. All three of the men received life sentences, with one of them serving 30 years before being deported to his native China, and the Wah Mee Club never reopened.

[Image by Joe Mabel via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

West Virginia: Matewan Massacre (1920)

The mining wars of the early-20th century were an extremely tumultuous era in American history, and unfortunately, they produced many tragedies. One of the worst was the Matewan Massacre, which took place on May 19, 1920, in Matewan, West Virginia. After coal miners in Matewan went on strike to protest use of private guards at the mines, they were kicked out of their company housing and illegally evicted from the makeshift camp they had set up outside of the company's jurisdiction.

When the local sheriff, who was more sympathetic to the miners' cause, arrived at the camp to investigate, he was met with resistance from the detectives who were hired to evict the miners. When the detectives couldn't produce a warrant and couldn't back up claims they had a court order, things exploded into a massive shoot-out at the train station between the miners and the sheriff. It resulted in the deaths of seven detectives, including the ringleaders, and three of the townspeople, including two miners and the mayor.

Afterwards, the strikers and sheriff were charged with murder and not the detectives. They were ultimately acquitted a year later.

The sheriff was murdered by the same group of detectives he was responsible for killing at Matewan shortly thereafter.

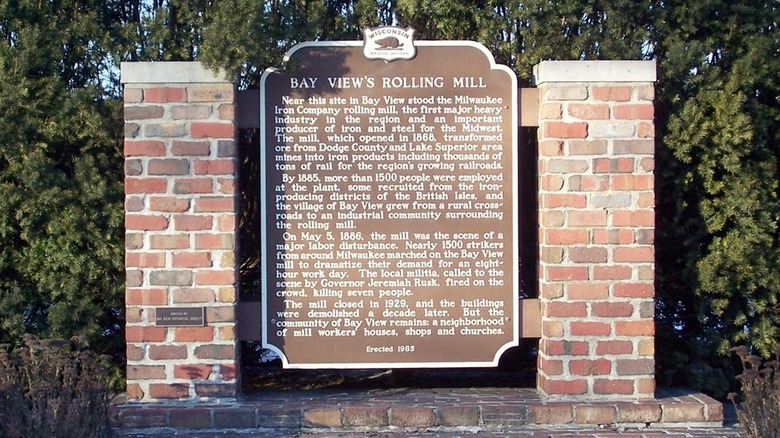

Wisconsin: Bay View Massacre (1886)

While most people don't generally think of Wisconsin as being a hotspot for labor protests, in the late-19th century it ended up being the site of one of the worst in history. In 1886, labor laws were much less favorable for workers than they are now, and laborers in Bay View, Wisconsin, began striking over having to work more than eight hours per day.

On May 5, 1886, one of the biggest labor demonstrations in Wisconsin history took place — 1,500 protesters went on strike, hoping to bring in workers from the Bay View Rolling Mills, the dominant area manufacturer. That's when things turned deadly. The state militia, on the side of the mill owners, opened fire into the crowd of marchers after they refused to stop demonstrating. In the end seven of the strikers were killed. One of the dead was just 13 years old, bringing a new level of tragedy to the incident.

Since the killing was essentially sanctioned, no one was ever held responsible over the murders, but the massacre is commemorated annually by local politicians and residents.

[Image by Sulfur via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]

Wyoming: Rock Springs Massacre (1885)

A product of rampant anti-Chinese sentiment of the 1880s, the Rock Springs Massacre is one of the worst racial killings in American history. Prior to the massacre, at Rock Springs tensions had grown between Chinese and white miners in the area following a series of strikes in the 1870s. As a result of the strikes, Chinese miners were brought in to replace white miners, and by 1885 there were roughly 600 Chinese miners compared to just 300 white miners.

White miners became increasingly outraged that Chinese workers were taking jobs and refusing to demand higher wages, and on September 2, 1885, they decided to take action. After amassing a huge mob consisting of white men, women, and even children, they attacked the miners' residences at Chinatown, killing 28 Chinese and injuring 15. The white miners shot many of the miners to death, and then proceeded to rob their homes before burning all 79 to the ground.

In the midst of the violence, hundreds of Chinese miners fled the area in fear of their safety. However, officials tricked them into returning, and they had to rebuild their torched town. Though several of the white miners were arrested, no witnesses were willing to speak up, so they walked.