History Of Fascism Explained

In modern political discourse, the terms "fascism" or "neo-fascism" are some of the most charged and polarizing possible. Yet, they are also some of the most overused and misunderstood. Take U.S. politics, for example: Both liberal and conservative parties have publicly accused each other of being "fascist" in some respect or another, and many people argue it's devaluing the meaning of the word to keep throwing it around so haphazardly.

So what does the term fascism even mean, and is anyone even using it correctly at this point? The term fascism describes a large political movement that occurred in Europe from the late 1910s until the end of World War II. Fascism was an ideology and system of government that served as the antithesis of liberalism and democracy in the early 20th century.

Though they were all different, fascist governments generally emphasized leadership by a single individual, a dictator, who promoted extreme state nationalism through laws and violence. Unlike liberal democracies, fascist governments were totalitarian and did not tolerate political protests or dissent, and they had foreign policies that emphasized a maximalist approach to gaining territory through militarism. In several cases, like Nazi Germany, fascism and anti-Semitism combined to form a horrifying supernova of evil. World War II largely extinguished the original wave of fascism. Unfortunately, it left the equally dark neo-fascism — or modern fascism — in its wake, and the term is still widely used today.

Fascism's uncertain origins

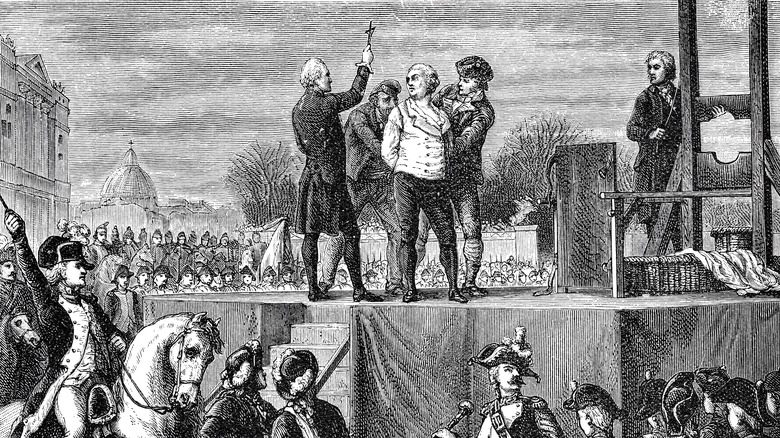

The philosophical and political origins of fascism are still being debated, largely because there were multiple fascist governments in the early 20th century who did not share the exact same ideology and philosophy as each other. In many respects, fascism can be seen as an outgrowth of the Jacobin movement during the French Revolution, which took place in the late 18th century. The Jacobins were a group of liberal social radicals who briefly controlled the French government during the revolution. They promoted egalitarianism, but also used harsh violence during the so-called "Reign of Terror" to maintain loyalty to the new government.

In contrast, others place the origins of fascism a few decades later, in the 19th century, as a conservative and negative response to the Enlightenment of Europe. The Enlightenment was a period that began in the 17th century and lasted until about 1800, during which European intellectuals espoused ideals of liberalism. Liberalism promotes the idea of individual liberty and reasoning, which fascist governments suppress in favor of obedience to the government.

The first overtly fascist governments in Europe came about during the upheaval of the end of World War I, when citizens in the losing countries were looking at uncertain futures. The social turmoil of the time created the right conditions for fascist ideals about violent justice, orderliness, and anti-democracy to take hold, and they were first popularly articulated by one man: Benito Mussolini.

Benito Mussolini: The first fascist dictator

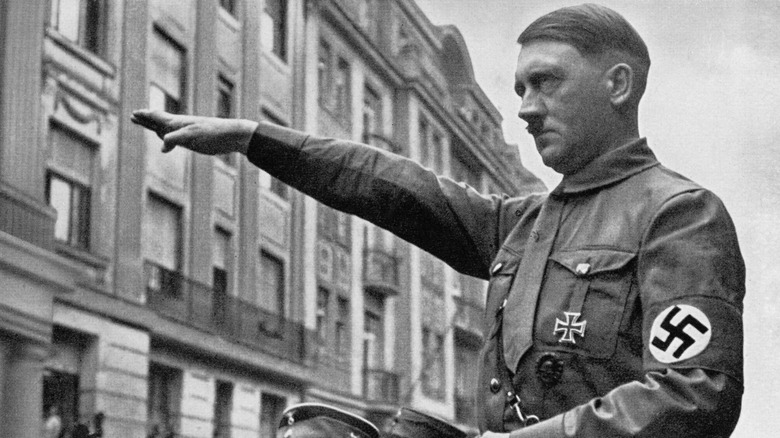

Fascism may be commonly associated entirely with Germany's Adolf Hitler, which is probably due to the role of the Nazis in World War II and the tragic Holocaust. However, in terms of fascism's origins, the more appropriate dictator to focus on, at least in its formative years, is Benito Mussolini of Italy.

Mussolini was born in 1883 in Italy, to an incredibly poor family, and he was a bully to others, often getting himself in trouble for committing violence against schoolmates. He became interested in socialism in the early 1900s, getting arrested several times and editing a socialist newspaper that opposed Italy getting involved in World War I. However, Mussolini soon started to clash with his fellow Italian socialists when he changed his mind about the war. He ended up joining the Italian army, believing that he was fighting for a unified and strong Italian future.

Yet, Italy's loss in the war and his battlefield injuries completely changed him, and his ideas morphed from socialism into proto-fascism. In public speeches, he began emphasizing anti-democratic and totalitarian rule by a strongman to resurrect a shattered Italy, and in 1919 he created the "fasci Italiani di combattimento" or "Italian fighting bands."

He targeted socialists and communists over their opposition to the war, as well as for their labor strikes that were hurting the country economically. In 1921, he renamed the "fasci Italiani di combattimento" as the Italian National Fascist Party: the first fascist party in history.

The march on Rome and the first fascist state

One of the most seminal moments in the rise of fascism was undoubtedly the October 1922 march on Rome. After Benito Mussolini created the "fasci Italiani di combattimento" in 1919, many of his supporters began to dress in black shirts, which soon earned them the moniker of the "blackshirts." Yet, the blackshirts weren't making a fashion statement, instead they were signifying their status as violent gangs of fascist street fighters. They were officially called "Squadre d'Azione," or "Action Squads," and aimed to convert people to Mussolini's burgeoning fascist program through extreme violence and terror. Their main targets were socialists and communists, who were some of their biggest political rivals, and they killed hundreds who opposed them in the process.

On October 24, 1922, things came to a head at a meeting of fascists taking place in Naples. Following the meeting, during which Mussolini gave a rousing speech about insurrection, the fascists marched on Rome. On October 29, the Italian King Victor Emmanuel was forced to appoint Mussolini as prime minister, giving him control of the government.

When Mussolini became prime minister, his fascist state quickly went into full effect. He endorsed corporatism, which organized society and economic services into "corporations" (labor unions) that served the state and were under government control. The new fascist Italy was built on a strong culture of militarism, totalitarianism, and extreme obedience to authority, and set the stage for other fascists in Europe to take hold.

Hitler & the rise of Nazism

Following the genesis of Benito Mussolini's fascist Italy in 1922, the next major European state to turn to fascism was Germany, led by Adolf Hitler. Hitler was born in 1889 in Austria, but moved to Germany in 1913, and there joined the military. Like Mussolini, he was injured fighting in World War I, and came back home determined to change Germany's political makeup.

The Nazis called their brand of fascism "National Socialism," and following Mussolini's march on Rome, Hitler first tried to bring the Nazis to power in 1923 during the infamous "Beer Hall Putsch" insurrection, but failed horribly and ended up in jail for treason. Following his release from prison, Hitler used the ongoing political instability from the Great Depression in the 1930s to undermine faith in the government and drum up support for the Nazis. After building up the Nazi's electoral strength, he became German Chancellor in 1933, and created the second fascist state in Europe.

Hitler's fascism had a lot in common with Mussolini's, but differed in many significant ways. Like Mussolini's fascism, Nazism embraced militarism, dictatorship, anti-Marxism, anti-liberalism, and anti-democracy. However, Nazism also included a hierarchical and anti-Semitic view of race, where "Aryans" were at the top and Jews were at the bottom. Hitler saw Nazism as a means to create a unified German people — or Volk — free from Marxists and Jews, who he saw as threats to progress and German solidarity.

The other fascists of Europe

The two most well-known fascist movements of Europe in the interwar years may be that of Benito Mussolini's Italy and Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany, but there were several other fascist groups taking power during that period. Besides Italy and Germany, fascist governments took hold in Austria, Portugal, Greece, Romania, briefly Norway, and Japan in the years before World War II. In addition, there were also strong fascist political movements in countries that otherwise did not completely succumb to the ideology.

Of the countries that did fall to fascism in the 1920s-1930s, some of the more notable for the magnitude they did so were Engelbert Dollfuss' Fatherland Front in Austria, Ioannis Metaxas' Party of Free Believers in Greece, and Tojo Hideki's military dictatorship in Japan. Austria later merged as part of Germany during the 1938 Anschluss, and Japan fought alongside Germany and Italy during World War II. During the Spanish Civil War from 1936–1939, Italy and Germany supported Francisco Franco's Nationalists against the Republicans, helping them reach victory and installing a quasi-fascist government in Spain.

In France and England, fascism threatened to take hold in the forms of the French Cross of Fire and under Englishman Oswald Mosley, respectively. Mosley was able to rally 50,000 to the British Union of Fascists, but the movement collapsed after he was imprisoned in 1940. The Cross of Fire boasted as many as 1.2 million members in France, but never took control of the government.

The climax of fascism: World War II

The heydays of the worldwide fascist movement began in 1922 with the formation of fascist Italy, and ended in 1943 when the Allies took over Italy and started reversing Axis gains in World War II. In 1936, the fascist governments of Italy and Germany formally allied as part of the Rome-Berlin Axis, which moved to include fascist Japan in 1940 shortly after the war broke out.

At first, the war proved to be a resounding success for these fascist governments, as Germany made extreme territorial gains in a relatively short period. By the summer of 1942, fascism had reached its apogee. Germany was in control of much of Western and Eastern Europe, and Italian and German forces were advancing in Northern Africa and into British-controlled Egypt. Yet, starting with the second Battle of El-Alamein in October 1942, everything went downhill. The Allies had defeated the Italians in Northern Africa by May 1943, and a month later they formally invaded Southern Italy. Fascism's collapse had begun.

By August 1945, Adolf Hitler and Mussolini were both dead and the fascist governments of Italy, Germany, and Japan were no more. Their epic defeat and the revelations of the Holocaust left fascism soundly discredited. In Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union's brand of communism officially replaced any vestiges of fascist rule, and in the West, the United States assiduously worked to replace fascism with liberal democracy.

The rise of fascism, anti-Semitism, & the Holocaust

The two biggest fascist entities of Europe in the lead-up to World War II — Italy and Nazi Germany — had very divergent views of how race and Judaism played into fascism. When Benito Mussolini first came to power in the 1920s, he publicly supported Jewish fascist organizations, and anti-Semitism was not a significant part of Mussolini's rise. Yet, the Mussolini government was always unabashedly racist. They believed that white Europeans were superior to Black Africans, which played a role in the Italian invasion and conquest of Ethiopia in the mid-1930s.

In contrast, Adolf Hitler was xenophobic and anti-Semitic well before he took power in the 1930s, and he used both to drive his fascist Nazi ideology and gain supporters. He published his book, "Mein Kampf," in the mid-1920s, which was an explicitly racist and anti-Semitic tract that called for the elimination of Jews and the proliferation of the (contrived) Aryan race.

Even though they were allies during the war, Italy and Germany never saw face-to-face on anti-Semitism. While Italy did start implementing anti-Semitic laws in 1938, they were reluctant to aid Hitler's mass killing of the Holocaust, and, in many cases, resisted demands for their deportation.

The early neo-fascists

When Italy and Nazi Germany collapsed at the end of World War II, so did fascism along with them. In the aftermath, many governments, including Germany, went as far as to outlaw Nazism and fascism legally. However, the ideas that led to such powerful states as fascist Italy and Nazi Germany were not eliminated so easily, and they remained festering within certain groups around the world. While the term fascism is used to describe the governments that took hold up until 1945, the term neo-fascism describes movements of similar ideology in the years after the war.

Importantly, while neo-fascists often ascribe to many of the same ideals surrounding militarism, nationalism, and anti-liberalism, they also evolved with the changing political landscape of 1950s-1970s Europe. This meant in addition to rampant anti-Semitism, neo-fascists found other targets for their hatred and scapegoating, such as new immigrants — mainly from the Middle East and Africa. Many groups of neo-fascists also merged with groups of neo-Nazis.

Instead of a foreign policy predicated on maximalist expansion, neo-fascists preferred to wage war for urban areas of cities, often attacking poor immigrants in the inner cities. They also began to feign a dedication to democracy in an attempt to gain mainstream credibility, and by the late 1940s, there were already reformed fascist parties in Italy and Germany, a sad indication of things to come.

Neo-fascism proliferates in Europe

By the end of the 1990s, though massively disgraced after World War II, some neo-fascist political parties began to score inroads with the European electorate. In addition, the rise of the conservative "far-right" in politics has blurred the lines between modern neo-fascist and conservative-nationalist parties. Many of the "far-right's" tenets — including anti-immigration and white supremacy — are identical to that of neo-fascism, making it hard to distinguish between them in the European electorate.

In Italy, Benito Mussolini's granddaughter Alessandra Mussolini (pictured above) nearly became the mayor of Naples in 1993, running for the Italian Socialist Movement (MSI) — a party that explicitly endorsed her grandfather's fascist past. In 1995, the MSI's successor party was able to capture 14% of the Italian vote, and from 2008–2013, the former party secretary of the MSI, Gianfranco Fini, was president of the Italian Chamber of Deputies.

In Germany, the lines between postwar neo-fascist and neo-Nazi parties were consistently blurred, with former Nazis heading several fascist parties. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, many German neo-fascists and neo-Nazis got together to form increasingly far-right parties. As of 2023, nearly one-fifth of the German electorate voted for the far-right "Alternative for Germany," a trend that has been steadily kicking upward over the years.

Fascism in the United States

Fascism as a political movement found its most fertile ground in Europe, but never really took a significant foothold in America. Prior to World War II, no fascist party ever seriously threatened Republicans or Democrats in major elections. The one fascist organization that saw any meaningful inroads, the German-American Bund, was tainted by its association with Nazism and collapsed even before America entered the war.

After the war, neo-fascist groups did spring up in isolated areas around the United States, but have never seriously threatened to take hold of any electorate. However, neo-fascism has still proliferated in the U.S. ... somewhat. Like Europe, many neo-fascist groups in the United States are synonymous with "far-right" groups, and the lines separating them are very blurry. Some of the most infamous of these groups in the United States are the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers, with the paramilitary activity of the latter drawing comparisons to Benito Mussolini's Blackshirts.

Some have compared the presidency of Donald Trump to neo-fascism. They point to his anti-immigration comments and policies, his courting of far-right groups and refusal to disavow even the explicitly racist and anti-Semitic ones, and his support among members of the far-right movement. However, not everyone agrees, and many consider this association an exaggeration.

The end of fascism?

By the 2020s, the traditional fascist movement had long run its course, and for the most part, the term cannot be appropriately applied to modern politics. The era of fascism existed largely in Europe from the late 1910s until the end of World War II, when the fascist dictatorships of Italy and Germany were destroyed. But neo-fascism was born in the ashes of the war, and proliferated around Europe for several decades. Stateside, fascism never took hold, as the ideas of totalitarianism and authoritarianism were an antithesis for Americans from the beginning. However, many have argued that neo-fascism found various vestiges around America, and some even claim that former President Donald Trump was the 21st century incarnation of American fascism.

Yet, what now remains of the modern neo-fascist movement is virtually indistinguishable from that of the conservative "far-right," and almost nobody refers to themselves as a fascist in serious political discourse at this point. While the term is still used a lot, the actual historical phenomenon of fascism ended many decades ago, though its remnants still soil the political waters worldwide. And in Europe, where fascism begun, the ideological — and sometimes literal — descendants of the founders of the fascist movement are walking the halls of power.