The Entire Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Explained

The shocking attacks carried out by the militant Hamas terrorist organization against Israel in early October 2023, brought new attention to one of the longest simmering and most violent struggles in the world: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The area of present-day Israel has long been a battleground for the competing movements of Zionism and Palestinian Nationalism, and things have often turned incredibly destructive. For decades, the front pages of newspapers worldwide have reflected the turmoil in the area, and things hardly seem to be getting more peaceful.

The struggle is for control of the territory of historical Palestine, which is largely a part of present-day Israel. The fighting has led to thousands of deaths on both sides and a massive refugee problem in the West Bank and Gaza. In 1950, there were about 750,000 Palestinian refugees, but that number has swelled to 5.9 million by the early 2020s, and many of them are living in appalling poverty today (according to the United Nations).

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is incredibly nuanced and delicate, and there are strong feelings from participants on all sides. From its modern-day origins in the 19th century through the October 2023 Hamas terror attacks, this is the history of the entire Israeli-Palestinian conflict explained.

Zionism and Palestine

In the late 19th century, the Jewish communities of Europe faced widespread intolerance. In Western Europe, their peers discriminated against them and viewed them as socially inferior, and in Eastern Europe, Jews were often the victims of violent pogroms, which were attacks by mobs that left many dead and wounded.

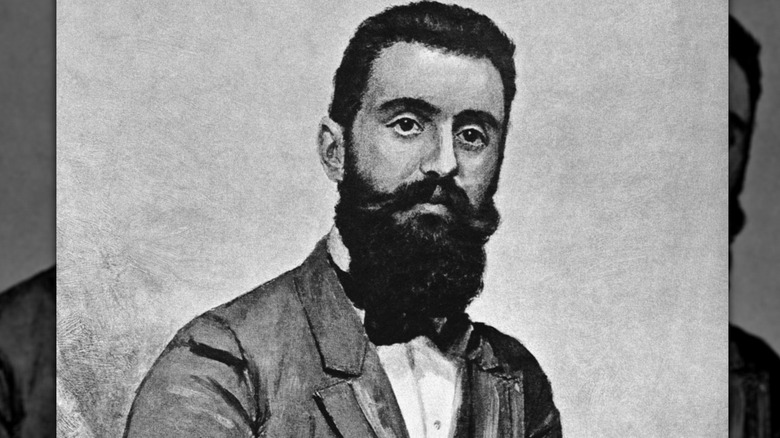

This anti-Semitic attitude pushed European Jewish intellectuals and political activists to agitate for a solution to the growing prejudice, and this movement eventually became known as Zionism. Early Zionist thinkers like Theodor Herzl (pictured above) and Leon Pinsker wrote tracts discussing solutions to combat anti-Semitism, and they began to engage many of their peers. Herzl and Pinsker argued that the answer to the question of the Jews' discrimination in Europe was the creation of a separate Jewish homeland, where Jews could live in peace and freedom. From the beginning, the Zionists were split on how to incorporate Judaism, and many religious Jews rejected and actively rallied against Zionism. Some of the earliest Zionist leaders saw the movement as more secular than religious, arguing the Jewish community was a dispersed nation and not just a religion.

Beginning in the 1880s, various Jewish groups began to encourage immigration to Palestine to escape the increasingly nasty Russian pogroms. In 1884, Pinsker organized a conference in Katowice, Poland, to merge these groups and the Zionists together as the "Lovers of Zion," and in 1897, the Zionists officially named Palestine as the place for the Jewish homeland — but no one told the Palestinian Arabs.

Early immigration and tensions

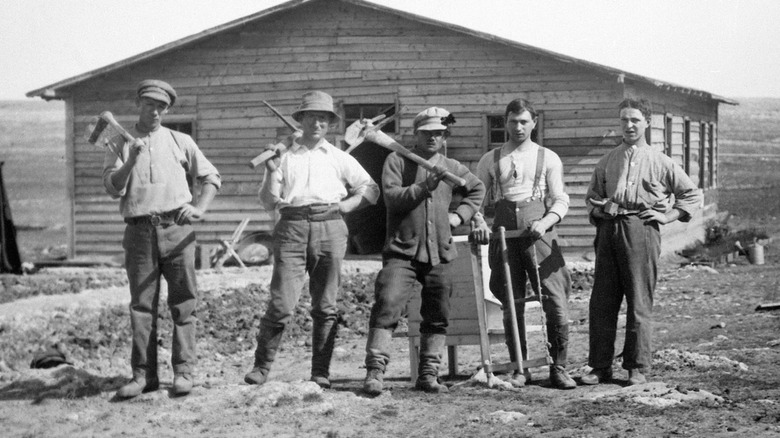

In 1878, before Zionist immigration began, Palestine was overwhelmingly Arab. According to the 1878 Ottoman census, there were only roughly 25,000 Jews compared with the more than 400,000 Arabs who made up over 85% of the population (via Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East). The initial Zionist immigration to Palestine occurred in several waves, the first of which began in 1882 and saw the first Jews make it to Palestine from Russia.

By 1914, the Jewish population had more than doubled since 1878 to 60,000, but the Arab population had also increased to 731,000 (via ProCon.org). Much of the land the Zionists settled on was purchased by large Zionist and Jewish organizations, like the Jewish National Fund, which they bought from absentee landowners and not the Arab peasantry themselves. The land acquisitions quickly brought the Zionists into conflict with the Arab residents, who were often working the land when it was sold and were subsequently kicked out.

In addition to tensions over land, Zionism began to conflict with the burgeoning Arab nationalist movement among the Palestinians, which sought to unite the larger Arab world together. They saw the Zionists and a Jewish state as impediments to that goal, and relations between the two groups deteriorated quickly. Not yet awash with violence, this was probably the most peaceful time in the entire Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The Balfour Declaration

Prior to World War I, Palestine was officially part of the Ottoman Empire. However, by the end of the war the British had overtaken the Ottomans, which they achieved with the help of the Arab people through the Arab Revolt. Yet, at the same time, the British cabinet began to drift into the Zionists' political orbit as prominent Zionists made inroads with British politicians.

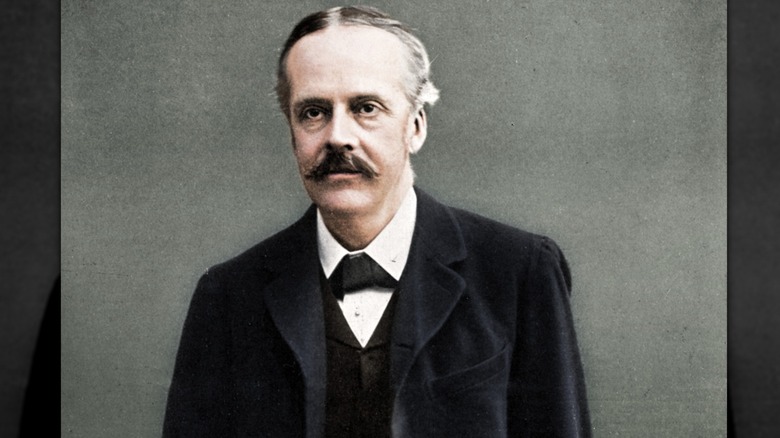

By 1917, the Zionists' actions began to bear fruit, and on November 2, 1917, the British issued the now famous Balfour Declaration. The declaration was named after its author, Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary, who wrote: "His Majesty's Government view[s] with favor the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people." While the letter also promised safeguards for the "non-Jewish communities in Palestine," the Arabs officially rejected the declaration.

When the war ended, Palestine entered the League of Nations' mandate system, which was created to help govern former Ottoman territories until they formed sustainable governments of their own. Britain officially gained control of Mandatory Palestine in 1923, and it was clear the British prioritized creating a Jewish rather than an Arab state. The formal mandate included the language of the Balfour Declaration, and it recognized a Jewish Agency to speak for the Zionists while the Palestinian's Arab Executive was afforded no such acceptance. In addition, many British officials were pro-Zionist and harbored racist feelings towards the Palestinian Arabs. Already, the odds seemed to be against the Palestinians and favoring the Zionists.

Mandatory Palestine and the Arab Revolt

From 1922–1936, the Jewish population in Palestine increased by over 300,000 to almost 30% of its total, bringing Zionists and Arabs into closer contact and leading to increased tensions (via CJPME). In 1929, disturbances in Jerusalem at the Wailing Wall led to the deaths of 133 Jews and 116 Arabs, but no appreciable change in British policy followed as they ignored recommendations to limit Zionist immigration. With tensions brewing and the British seemingly favoring the Zionists, it was only a matter of time before the powder keg erupted.

Unhappy with their ineffective leadership and increasing Zionist immigration, the Arabs staged a large-scale strike and revolt from 1936-1939. Disturbances began in April, when Arabs murdered a Jewish bus passenger, and soon, a local strike morphed into a nationwide Palestinian movement. There were violent attacks on both sides, leaving 1,000 Arabs and 80 Jews dead within six months.

From October 1936 until July 1937, the strike was on hold along with the violence, and the British sent in an investigative commission. Yet, when the commission recommended a separate Jewish and Palestinian state, both sides rejected it. During the renewed revolt, Palestinians murdered Jewish settlers and began terrorizing the countryside with armed bands, hoping to end the Zionist experiment in their homeland. The revolt conclusively failed, and the British army and Zionist paramilitaries finally put down the disorder in March 1939, but by then there were already 5,600 dead, a little over half of whom were Arab. Palestine was crumbling at the seams.

Palestine and World War II

Following the Arab Revolt of 1936–1939, Palestine was in complete shambles. During the uprising, the British dissolved the Palestinian leadership and deported most its members, leaving much of the movement in the hands of rebel bands and the peasantry. The revolt had failed in its primary goal of removing the British and their support for the Zionists' claim to occupation, but the British did moderate their policies towards Palestine afterward.

After the uprising, the British announced "The White Paper," which was a complete break from their previous policies. It repudiated the idea that Palestine was meant to be a Jewish State, restricted Jewish immigration to 15,000 a year, and stopped certain land transfers from Arabs to Jews. The British issued the White Paper just as the Holocaust was beginning, leaving the Jewish community incredibly upset and disenchanted. When fighting broke out in the Middle East during the Second World War, however, it was Zionists and not Arabs who fought alongside the British. While the Zionist paramilitaries gained munitions and valuable combat experience fighting with the British, the Arabs were afforded no such opportunity.

After the war, the Zionists were determined to remove the British from authority over Palestine and declare independence. They lashed out violently through acts of sabotage and terror, such as the bombing of the British's HQ at the King David Hotel in 1946 that killed 41 (via The New York Times). Once again, Palestine was engulfed in turmoil and bloodshed.

The United Nations decides on Palestine

By 1947, Palestine's situation had deteriorated to the point of irreconcilability, and the British needed an exit. By then, the League of Nations was defunct and had been replaced by the United Nations. In February, the British presented the Palestine question to the UN. However, reaching a satisfying answer was far from easy.

By the end of 1946, the population stood at roughly 1.84 million inhabitants, with only 33% being Jewish and 58% being Muslim-Arab (via the UN). In addition, even after decades of land transfers, the Zionists only controlled 6% of the land in Palestine. While on the ground the Arabs seemed to have the stronger position, at the UN, it was a different story. The Zionists effectively mobilized influential American supporters to pressure UN delegates to vote favorably for them. In contrast, the Palestinian leadership had been in exile since the failure of the Arab Revolt, leaving them largely without close representation. On behalf of the Palestinians spoke the leaders of the surrounding Arab states, but they were more concerned with appearing to care, rather than actually creating a Palestinian State.

In November 1947, the UN issued Resolution 181, but it was a solution beset with problems. UN 181 recommended Palestine be partitioned into both Jewish and Arab states, which was an immediate anathema to the Palestinians who controlled most of the land that was earmarked for the Zionists. Assured by the surrounding Arab states that they would back them militarily, the Palestinians rejected UN 181 out of hand, while the Zionists supported it.

War in Palestine

In late 1947, as the British withdrew and the United Nations stood by, Palestine devolved into hellish violence. Within 24 hours of the UN's announcement of their partition plan, Arabs began attacking and shooting at Jews in Haifa and Tel Aviv, and fighting soon erupted between them. Both sides targeted civilians, including bombing public areas, and seemingly nobody was safe.

Importantly, many of the Zionist paramilitaries were experienced and well-coordinated, and they were far superior in combat compared to the less-organized Palestinian resistance. By the spring of 1948, things had largely shifted to the Zionists. Punctuated by atrocities against civilians like the shocking Zionist massacre at Deir Yassin, which left over 100 Arab villagers dead, the Palestinian resistance began to crumble.

On May 15, 1948, Israel formally declared independence, though this hardly ended the bloodshed. Instead, the Arab countries of Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and Transjordan invaded Israel, intending to evict the Zionists in favor of the Palestinian Arabs. However, the Israelis had a numerical superiority of forces and a strong determination to win, and they threw back the invading armies in a stunning victory. When it was all over in July 1949, Israel controlled almost all of the territory designated for themselves and Palestine according to UN 181, except for the Gaza Strip near Egypt, and the West Bank, including Old Jerusalem. Known in Israel as the War of Independence, the Palestinians have a different name: Al-Nakba, or the catastrophe.

The refugee crisis and continued tension

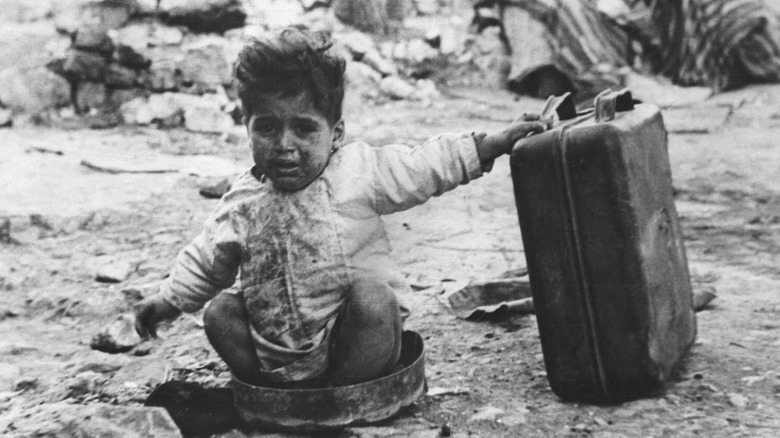

Perhaps the worst legacy resulting from the 1947–1949 Palestinian Wars was the giant refugee crisis left in its wake. Amidst the violence, many Palestinian Arabs fled Israel to the nearby Arab countries of Syria, Lebanon, and Transjordan, as well as the Egyptian Gaza Strip. It's widely estimated that at least 750,000 Palestinians were left displaced by the fighting.

Israel and the Palestinians were unable to agree on terms to readmit the refugees, and as a result, none were. Israeli settlers quickly moved into former Palestinian homes and villages, now bereft of their former owners, while the Palestinians languished in scattered and squalid refugee camps. Even while the fighting was still ongoing, thousands of refugees illegally made their way back into Israel, often looking to reclaim pieces of their former lives, like clothing or crops they had been attending to when the war broke out.

In 1956, when the Suez Crisis broke out in Egypt, things again turned dark in Gaza. The Israelis invaded Egypt on October 29, and within days there were reports of several massacres of Palestinians in Gaza. By 1964, the Palestinian situation was increasingly destitute, but that year sparked a small beacon of hope for Palestinian unity: the creation of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO). The PLO was the first organization run by Palestinians for the benefit of their people, and it offered them a semblance of optimism.

The Six-Day War of 1967 and the beginnings of occupation

On June 5, 1967, Israel went to war with three neighboring aggressor states, which would be known as the Six-Day War for its brevity. By the war's end on June 11,1967, Israel had destroyed the Egyptian, Syrian, and Transjordan armies, and had gained the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza, the West Bank and Jerusalem, and even the Golan Heights from Syria. In short, it was a cataclysmic change.

For the Palestinians, it meant even more displacement and hopelessness. Amidst the fighting, around 380,000 refugees fled camps in the West Bank, Gaza, and Golan Heights to the surrounding Arab states. In addition, now occupying these areas, Israel absorbed 1.5 million Palestinian refugees into their borders. It was hardly a stable situation.

Politically, the collapse of the Arab armies during the fighting completely disenchanted the Palestinians with the wider Arab leadership. After nearly two decades, they were no closer to reclaiming their pre-1948 homes, and the failures in June seemed to underscore the impossibility of them ever returning. To make matters worse, the Israelis began to create settlements in their newly conquered areas from Syria and in East Jerusalem in the West Bank, at times evicting Arabs to make way for Israeli settlers. This angered the Palestinians and caused international outrage, and late in 1967, the United Nations passed Resolution 242, calling for Israel to leave the territories. However, ambiguous language allowed Israel to claim a legal basis for the occupation, which still exists today.

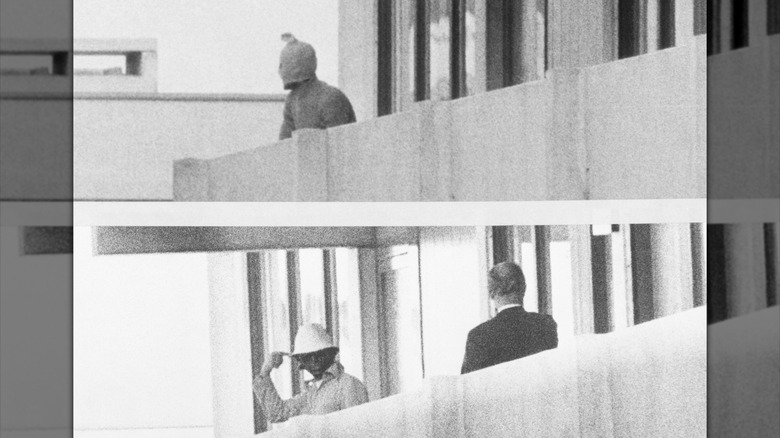

Munich and the 1973 War

Following the 1967 Six-Day War and the start of the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories, things declined even further for the Palestinian refugees. The actions of many in the Israeli government, like Prime Minister Golda Meir, who refused to acknowledge their existence, only angered the Palestinians further. Feeling ignored on the world stage and confined to filthy and fetid refugee camps, a small minority of Palestinians began to violently lash out.

Some of the worst attacks were the Lod Airport massacre in 1972, which left 25 dead and 72 wounded (via The New York Times), and the Kiryat Shmona massacre in 1974, when Arab gunmen killed 18, including many women and children (via The New York Times). Both of these attacks were carried out by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a terrorist group based in Palestine. At the 1972 Munich Olympics, the Palestinian-affiliated terrorist group Black September kidnapped several members of the Israeli Olympic team, and in the ensuing struggle, all 11 Israelis died at their hands, causing international outrage.

In 1973, Israel was once again thrust into combat against its neighbors during the Yom Kippur or Ramadan War, which ended with important political consequences. Israel defeated the Egyptians and Syrians in the fighting, and by the end of the fighting, Israel was firmly aligned with the United States. Once again, the Palestinians found themselves left out in the cold, and the attacks by terrorist groups continued.

The PLO, Lebanon, and Camp David

By the late 1970s, the conflict in Israel was again beginning to bleed into the surrounding Arab states, and in particular Lebanon and Egypt. Lebanon was already in turmoil from an ongoing civil war since 1975, and it became a haven for many militant Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) members following the 1967 Six-Day War.

By 1978, the PLO's presence in Lebanon was becoming untenable for Israel as they launched deadly cross-border attacks. In March, a terrorist assault killed more than 40 people in Israel and left at least 70 wounded. In response, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) invaded Lebanon, which resulted in more than 300 PLO deaths, 1,200 civilian deaths, and caused 100,000 more civilians to flee in panic. Later that year, the Egyptians, Israelis, and American President Jimmy Carter held peace negotiations at Camp David to discuss the future of the Sinai occupation, but the PLO was not invited. In 1979, the negotiations led to the Camp David Accords, and while Israel agreed to leave the Sinai (but not Gaza), the question of the Palestinians was left unaddressed, leaving them completely ignored.

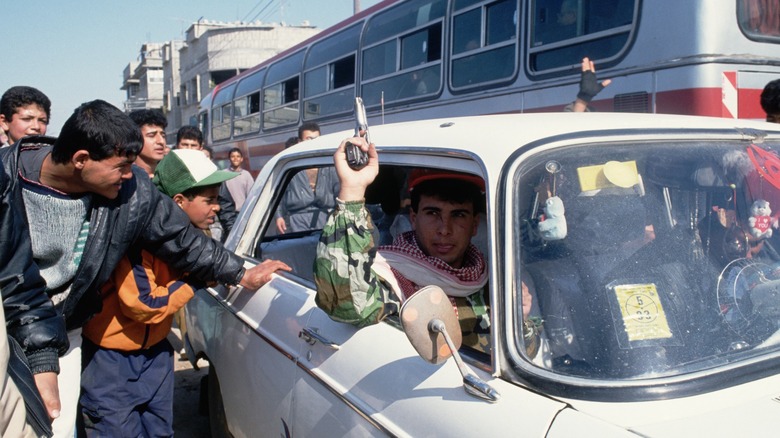

In 1982, the IDF once again entered Lebanon following the attempted assassination of an Israeli diplomat in London. They evicted 11,000 PLO from Beirut before leaving the city, though they maintained a presence in southern Lebanon for years to come. This again removed the Palestinian leadership from the Palestinian community, and did nothing to quell the overall chaos and tension.

The First Intifada and Hamas

By 1987, the Palestinians had endured 20 years of occupation and 40 years of displacement. They were becoming increasingly marginalized and subjugated under Israeli occupation, as the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) controlled and restricted nearly every aspect of their lives. The Palestinians were also upset over the increased number of Israeli settlers moving into occupied territories and Israel's oppression of Palestinian political activists.

In late 1987, the Palestinians' discontent finally boiled to the surface in what is known as the First Intifada. When IDF soldiers shot Palestinian protestors following a car accident in December, both the West Bank and Gaza erupted with violence. At the heart of the Palestinian struggle was a desire for national self-determination, meaning the creation of a Palestinian state. The Intifada lasted until 1992, gradually becoming more and more violent. At first, the Palestinians threw rocks and Molotov cocktails, but soon guns and explosives entered the picture as the IDF's reprisals intensified, which included shutting off water and electricity and destroying private property. By 1991, there were more than 1,000 dead Palestinians, over 37,000 more wounded, and another 35,000-40,000 had been arrested.

Politically, the Intifada dramatically changed the territories. A new militant terrorist group called Hamas formed in 1988, with the explicit purpose of replacing an Israeli state with a Palestinian one, and they started carrying out attacks against civilians and IDF soldiers. Within the territories, the Palestinian struggle had entered a new and much more violent phase and showed little progress for peace.

The Oslo Accords

The First Intifada had exposed deep rifts within Israel, not just from a refugee perspective, but also among Israelis themselves. The widespread violence and huge toll on the Palestinians put their plight front and center to the Israelis, and some of them began to openly sympathize with the Palestinians. This new attitude, along with the election of a more socially liberal Labor party, combined to create the atmosphere for the first ever comprehensive Israeli-Palestinian peace talks.

The peace process began with the 1991 Madrid Conference, which the U.S. had pushed for as a solution to the conflict. The Israelis met with a joint Jordanian-Palestinian delegation in Madrid, and public talks continued for a few years, but they were not very productive. However, secret negotiations directly between the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and Israel commenced, and those eventually led to the Oslo I Accords in 1993.

With Oslo I, for the first time, the PLO and Israelis mutually recognized each other as legitimate representatives, the PLO agreed to publicly renounce terrorism, and the accords also laid out a plan for future Palestinian self-government, though not a full state. In 1995, the Oslo II Accords were signed, which gave the Palestinians slightly more autonomy and control and called for Israeli forces to withdraw from some occupied areas. Internationally, expectations could not have been higher for peace in the Middle East, but all parties would soon be sadly shaken to reality.

The breakdown of Oslo

At first, there was widespread optimism and hope that Oslo could lead to a stable framework for peace, but both sides worked to undermine the accords with tragic efficiency. From the Palestinian perspective, the accords did little to alleviate their harsh living conditions, their already parlous economic situation still declined, the illegal settlements continued, the new Palestinian Authority (PA) was seen as corrupt, and the goal of an actual state seemed just as far away. In addition, militant terrorist groups like Hamas actively worked to destroy the accords through numerous terrorist attacks against the Israeli public.

From the Israeli perspective, the Oslo Accords were supposed to guarantee peace from terrorism, but Hamas shattered any illusion the PLO or PA could enforce peace measures and stop the bombings. In addition, the militant and terroristic factions of the Israelis committed their own atrocities, such as when an Israeli settler killed 29 Palestinians at a Mosque in Hebron in 1994, or when they assassinated their own Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995.

In 1996, the Israelis elected Benjamin Netanyahu as Prime Minister, which was a symbolic end to the peace process started in Madrid, as Netanyahu stopped implementing the Oslo agreements and began increasing the pace of settlements. The U.S. tried to salvage the peace process through the 1998 Wye River Accords, but these too, conclusively failed.

The Al-Aqsa Intifada

When the Oslo Accords collapsed in the late 1990s after years of acrimony, many people likely felt that the Israeli-Palestinian peace process was dead. The peace talks briefly restarted in 2000 at Camp David, but no accord was ultimately reached. With tensions already high over the breakdown of the peace process, the actions of conservative Israeli politician Ariel Sharon in September 2000 set off a new wave of violence.

Sharon took 1,000 supporters and marched on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, which also contains the sacred Al-Aqsa Mosque. Sharon wanted to demonstrate Israeli power, but his rhetoric and actions severely angered the Palestinians, leading to stone-throwing and demonstrations. In response, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) began shooting and killing demonstrators, and the Second or Al-Aqsa Intifada was underway. Peace talks later in the year once again broke down due to violence on the ground, and in 2001, the Israelis elected Sharon as the new prime minister.

Compared with the first, the Al-Aqsa Intifada was much more violent and characterized by intensive bombing campaigns from Islamic terrorists. Additionally, the Al-Aqsa Intifada was also much less widespread and less organized among the Palestinians, and it was also more costly. By the summer of 2003, 2,400 Palestinians and 780 Israelis died in the chaos.

Israel leaves Gaza and Hamas takes over

After the violence of the Al-Aqsa Intifada claimed thousands of lives, the Israelis began new tactics in the occupied territories. In 2005, the Israelis began "disengagement," or removing the illegal Jewish settlers from Palestinian territory. By August, the Gaza settlements were no more, but the West Bank settlements were untouched. Even worse for the West Bank, the Israelis began building massive barriers to separate the Jewish settlements from the Palestinians' areas. Additionally, they built them on Palestinian, rather than Israeli, land, reducing the Palestinians' territory even further.

In the 2006 West Bank elections, the terrorist organization Hamas won a stunning victory, taking control for the first time. In March 2006, Hamas formally took over the Palestinian Authority (PA), ushering in a new era for the West Bank. With Hamas' refusal to even recognize Israel's right to exist, any potential peace talks between the Israelis and PA were non-starters.

That summer, Hamas and their political rivals al-Fatah began open warfare in the West Bank, characterized by rocket fire and explosive grenades, and Hamas was in control of Gaza by the following summer. Rockets also made their way into Israel, and Hamas launched raids that ended with the kidnapping of an Israeli soldier. Beginning in 2007, due to security concerns over Hamas, Israel instituted a complete blockade of Gaza, extending over the land, sea, and air.

The 2008–2009 Gaza War

From the moment Hamas took over the Palestinian Authority in 2006 and gained control of Gaza in 2007, it was obvious they were on a crash course with Israel. In March 2008, Hamas sent hundreds of missiles over the Gaza border into Israel, and the Israelis responded with a two-day assault that killed 116 Palestinians (via The New York Times). Yet, by the end of the year, tensions were again rising. The Israelis launched a massive invasion on Gaza on January 3, 2009, after smashing Hamas with airstrikes the week prior.

Israel claimed the attack was in response to Hamas continuing to fire rockets into Israel, and on the day of the invasion, Hamas launched another 70 rockets, killing at least four (via The New York Times). After three weeks of warfare, the death toll reflected 1,200 Palestinians compared with just 13 Israelis, and the Israelis called for a ceasefire (via The New York Times).

Israel remained in Gaza until January 21, 2009, when they withdrew to the Gaza perimeter. Reports emerged that the Israelis had used white phosphorus during the fighting, which could have constituted a war crime if used against civilians. By the end, more than 1,300 Palestinians lay dead (via The New York Times).

Gaza and the West Bank in the 2010s

From 2012–2018, Gaza was permeated by sporadic violence between Hamas and Israel, and thousands of civilians were caught up in the bloodshed. In November 2012, Israel re-entered Gaza for eight days in response to more Hamas rocket fire into Israel, resulting in over 150 dead Palestinians and five dead Israelis before a ceasefire could take effect (via The New York Times).

In July 2014, Israel was back in Gaza, this time after Israeli teenagers had been abducted and killed by Hamas in the West Bank. The Israelis withdrew after another 1,881 Palestinians and 67 Israelis died (via The New York Times). In 2018, Gaza City was again aflame and awash with violence, as the Israelis killed at least 170 Palestinians between March and November, with Hamas retaliating with rocket fire (via The New York Times). It was an endless cycle of violence, and the civilians felt the brunt of the pain.

In the West Bank, which was not under Hamas control, things were also deteriorating at the same time. The refugee crisis was as bad as ever, and by 2021, the United Nations estimated there were at least 871,000 registered refugees in the West Bank alone. In addition, Israeli settlements expanded, causing the UN to issue Resolution 2334 in 2016, designating them illegal and calling for their demise.

Donald Trump and continued hostilities from 2021–2022

When Donald Trump became the president of the United States in 2017, it came after he extensively talked up Israel in his campaign. In late 2017, Trump acknowledged Jerusalem as the capital and began working to move the U.S. Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, which served to anger the Palestinians. In 2020, Trump helped broker the Abraham Accords, which called for Israel and the United Arab Emirates to establish normalized relations, while also getting Israel to suspend annexing the occupied West Bank.

However, Trump's actions did little to stop the violence on the ground in Gaza and the West Bank, and the killings continued. In May 2021, the Israelis evicted six families from a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem, which brought waves of protests. In response to the protests, Israel invaded, killing 20 and leaving more than 300 injured (via The New York Times).

The year 2022 was even more violent, and in March, Palestinian attacks killed 11 Israelis (via The New York Times). By the end of the year, after numerous Israeli reprisals, 166 Palestinians were dead in the West Bank alone (via The New York Times).

Hostilities in the West Bank and East Jerusalem

Much like 2022 ended for the occupied territories, 2023 began largely the same way, with Israeli raids into the West Bank. By January 26, 2023, 30 Palestinians already lay dead following raids into Jenin in search of Islamic Jihad terrorist group members (via The New York Times). That day, Palestinians in Gaza fired rockets at Israeli in retaliation, and on January 27, a Palestinian gunman shot and killed seven Israeli settlers outside a synagogue near a West Bank Israeli settlement (via The New York Times).

By June, the Israelis were using helicopter gunships during their Jenin raids, resulting in even more Palestinian deaths. As of June 19, 2023, the death toll for the year was already 130 Palestinians and 25 Israelis, setting it up to already be one of the worst years on record for both sides (via The New York Times). Still, nobody could've predicted what came next, as the next escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict would be one of the most devastating in history: the 2023 Hamas attacks.

The 2023 Hamas terrorist attack and war

On October 7, 2023, the Hamas terrorist organization viciously attacked Israel in one of the worst provocations in the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Hamas sent a barrage of rockets over the Gaza border into Israel, and carried out a devastating ground attack throughout southern Israel (via The New York Times). Within a day, there were already 700 dead Israelis, and the fighting was only beginning (via The New York Times).

In response to the attack, the Israelis immediately declared war on Hamas and began a counteroffensive, which claimed the lives of at least 1,500 and wounded more than 6,600 Palestinians in Gaza by October 13 (via The New York Times). In addition, the Israelis also shut off the power and restricted supplies of food and medicine. By then, the Israeli death toll had climbed to over 1,200 people, with more than 3,000 wounded.

Some of Hamas' most sinister plans included taking hostages, thought to be around 150 by October 13 (via The New York Times). Many of these hostages were taken from the Nova music festival that was underway when the attack was launched, and excruciating footage showed the militants murdering innocent civilians as they fled for their lives in terror (via CNN). The true devastation of the 2023 Hamas terror attacks won't be known for years, but it was the worst flare-up in decades.