The Origins Of Kwanzaa Explained

The oft-described, much-celebrated, and sometimes exhausting triple-whammy of holidays that hits America at the end of the year goes off the count of Halloween, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. But that leaves out the other December holidays, Hannukah and Kwanzaa. The latter, despite being an American innovation, has been waning in popularity in recent years. Per NPR, public recognition of Kwanzaa was on par with Christmas and Hannukah in the 1980s and '90s, but the National Retail Federation found it was only celebrated by 2% of Americans as of 2012. According to USA Today, this figure was roughly the same in 2019.

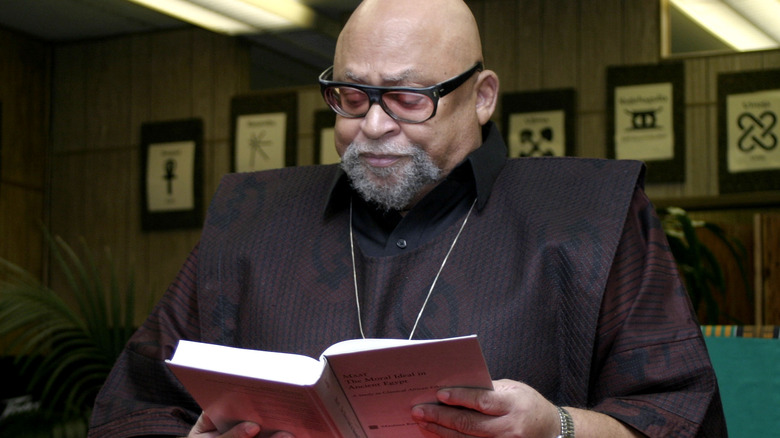

But that still comes to millions of people observing the holiday, which has undergone significant evolution throughout its history. And that history is a short one, because of all the year-end holidays, Kwanzaa is the only one with a definite creator and year of origin. It was the 1966 brainchild of Maulana Karenga, a professor and political activist. Born Ronald McKinley Everett, he came of age as the last vestiges of European colonialism in Africa were being challenged on the continent, and the civil rights movement was developing in the United States (per Keith A. Mayes' "Kwanzaa: Black Power and the Making of the African-American Black Holiday"). Karenga changed his name in 1963, associated with Malcolm X, and in the 1960s became a prominent figure in the Black Power movement.

Karenga has since become a major figure in Afrocentrism, and he created Kwanzaa in that spirit. In his book on the holiday, "Kwanzaa," Karenga says he invented the holiday to affirm African culture and drive communal celebration among the African diaspora.

Kwanzaa was based on African harvest celebrations

In creating Kwanzaa, Maulana Karenga drew on much older traditions. According to the official Kwanzaa website, harvest festivals from all over the continent provided inspiration. Such celebrations have been traced back as far as ancient Egypt, but Karenga's primary influence seems to have been the "first-fruits" celebrations in Southern Africa. He took the name from the Swahili phrase for first fruits, "matunda ya kwanza." According to Britannica, "kwanza" means "first" in Swahili, and the extra "a" was added to reach seven letters — one for each of the children who attended one of the first Kwanzaa celebrations.

Different groups throughout Africa still hold first-fruit festivals in December. In Swaziland, the festival is known as Ncwala and doubles as a celebration of the royal family. The Zulu people also combine the harvest with monarchial celebration under the name Umkhosi Wokweshwama. According to "Kwanzaa: Black Power and the Making of the African-American Black Holiday," it was the Zulu tradition that first caught Karenga's eye in his research, and he acknowledged Umkhosi as the inspiration behind Kwanzaa's seven-day period in his "Kwanzaa" book.

If not a harvest holiday itself, crops still serve among the seven symbols of Kwanzaa. Per the University of Central Florida, fruits, nuts, and corn were chosen as decorations to connect Kwanzaa to its first-fruits inspirations. Ears of corn are another symbol, though they were chosen to represent human fertility rather than agriculture.

The principles and iconography of Kwanzaa tie back to Africa

Maulana Karenga sought to tie Kwanzaa, in all its aspects, back into a pan-African ideal among all people and cultures of African descent. In an interview with the University of Central Florida, Africana studies expert Don Harrell said the colors of the holiday — red, black, and green — derive from the Black liberation movement. Red represents blood, green represents the Earth, and black represents the unity of the African people. Per the official Kwanza website, those also happen to be the colors of the flag of Organization Us, a Black nationalist group also established by Karenga.

The same three colors are used for the seven candles of Kwanzaa, which are meant to represent its seven principles, or nguzo saba. Those principles, each emphasized on a different day, are given in this order: umoja (unity), kujichagulia (self-determination), ujima (collective responsibility), ujamaa (cooperative economics), nia (purpose), kuumba (creativity), and imani (faith, in a familial and cultural sense). Karenga took the names of the seven principles from Swahili, which has not been without controversy. Per "Kwanzaa: Black Power and the Making of the African-American Black Holiday," Karenga considered it a "non-tribal" language, one that had a uniting effect among certain groups in Africa and the U.S. during the 1960s. But Swahili is only one out of thousands of African languages, and its origins are somewhat obscure.

Kwanzaa's creator has affected its popularity

Maulana Karenga has been an active proselytizer for Kwanzaa since its creation. Besides promoting its general celebration, he's pushed back on developments he considers detracting from the holiday's intended meaning. Notably, sections of his "Kwanzaa" book advise on how to fight its commercialization. Yet Karenga's reputation has sometimes acted as a turn-off for Black people who either don't celebrate Kwanzaa at all or who've given it up.

Though he now claims that Kwanzaa was never meant to replace Christmas, Karenga, he did initially see it as an alternative rather than a complementary holiday. He also once called Jesus "psychotic," according to Peter Heinegg's "Crazy Culture: The Sins of Civilization." Such comments have attracted pushback from religious conservatives, but for others, Karenga's actions during the 1960s and 70s are more upsetting. His Organization Us regularly clashed with the Black Panthers, and some hold him responsible for murders committed in those feuds (per Jacobin). As reported by The Baltimore Sun, he was also convicted of the assault and torture of two women in 1971 — charges he has always denied.

For some, like Chanté Griffin of the Los Angeles Times, Karenga's alleged failings don't take away from the meaning behind the holiday he created. But others, like Robbyn Mitchell of the Tampa Bay Times, find its pan-African aims incongruous with the diversity of African cultures. And in the years since Kwanzaa's creation, it's become much easier for Black Americans to celebrate and study their heritage as part of mainstream American culture, making the holiday obsolete for some.