The Only US President To Ever Be A Prisoner Of War

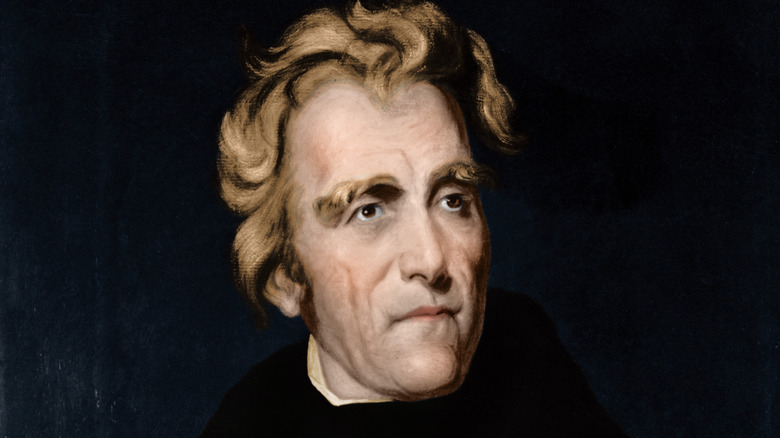

Was Andrew Jackson quite as rash as his reputation has made him out to be? To be sure, he was a hot-tempered man with a long memory for slights. His life included duels to the death, personally attacking his would-be assassin with a cane, and aggressive military campaigns that included the legally dubious invasion of Florida. And then there was the constant swearing, in such quantity and color that his parrot was allegedly taken away from Jackson's funeral for repeating some of his choice phrases. Against that, there is a happy family life, his political savvy, and a cohesive philosophy that forged an enduring coalition.

The caricature of a hotheaded leader may not suit Jackson when all the facts are weighed — not that such accounting undermines the modern case against him for his racism, support of slavery, and policy of Indian removal. Nor was Jackson free from moral criticism in his own lifetime. His heavy-handed control over his administration led to accusations of tyranny ("King Andrew I," critics called him), and his bitter rival John Quincy Adams branded him "a barbarian who could not write a sentence of grammar and hardly could spell his own name" (via The Independent).

Of course, Adams had good reason to resent the man who beat him in the 1828 presidential election. And he — like all the first six presidents — came from a more privileged background than Jackson. But that wasn't the only thing that set Jackson apart from his predecessors. He was the first — and, to date, the only — president who spent time as a prisoner of war, in the Revolutionary War no less.

He and his brother were captured together

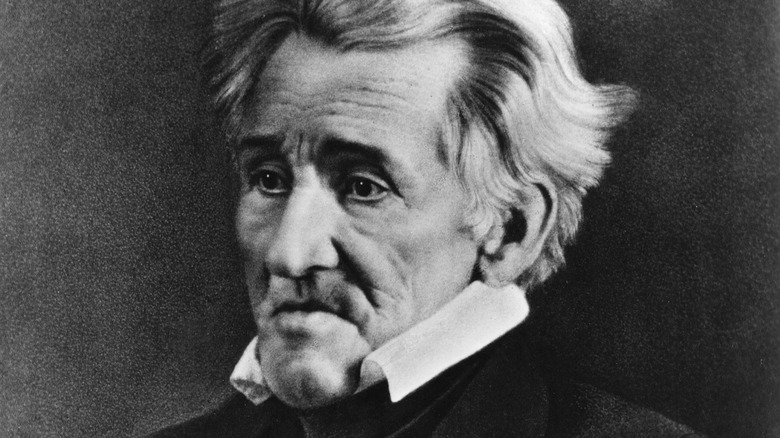

It's a matter of dispute exactly where Andrew Jackson was born. In 1767, the settlement of Waxhaw straddled the border of North and South Carolina, but he counted himself a native of South Carolina, one born to Scottish-Irish immigrants. By the time he came into the world, his mother Elizabeth was a widow. His father, Andrew Sr., was a poor man who died unexpectedly. Elizabeth, Andrew, and his two elder brothers lived with relatives, and at one point she was obliged to act as housekeeper for her sister's family.

Elizabeth brought with her from Ireland an intense hatred of the British, and while the American Revolution took several years to affect Waxhaw, the Jacksons were firmly in the Patriot camp. Elizabeth enlisted her younger sons, Robert and Andrew Jr., to help her tend to wounded revolutionaries, while her oldest son Hugo signed up to fight — only to die of heat exhaustion. After his death, Elizabeth urged her remaining boys to take an interest in the local militia. By the time he was 13, Andrew and his brother were volunteer fighters, and they became involved in a skirmish with Tories in 1781. The Jacksons escaped the fight, but when they attempted to fetch food the next day, they were taken prisoner.

The dragoon commander who took custody of the Jacksons ordered Andrew to clean his boots. Andrew responded by asserting his rights as a prisoner of war. Furious, the officer drew his saber and struck the boy across the hand and head. The scar remained with Andrew for the rest of his life.

The war made an orphan of Andrew Jackson

The sword strike, inflicted on Andrew Jackson and his brother both, was only a prelude. They and other captors were forced to endure a 40-mile trek without food or water to Camden, South Carolina. There awaited a jail with no beds, no medicine, and only the most foul rations. Conditions were so horrible that Jackson vehemently complained to an officer of the guard who chanced to speak to him, triggering an investigation and marginal improvement to the prisoner's lot.

Still, it was a grim captivity, made worse when a fleeting hope of rescue by Patriot forces was driven back. On top of everything else, smallpox was rampant in the jail, and Jackson and his brother Robert soon contracted the disease. They likely would have died in jail had their mother not been party to negotiations for a prisoner exchange. Both boys were still seriously ill when they were released into her care. Jackson had to make the trip home on foot without shoes or a jacket. But Robert was worse off, suffering an infected head wound and bowel issues on top of smallpox. He died within two days of reaching home.

It was a close call for Jackson, but he eventually made a full recovery, and his mother set off for Charleston to help nurse other prisoners of war. While on duty, she came down with cholera and died not long after the Battle of Yorktown. Jackson never discussed his feelings about being orphaned by the war, but his patriotism and regard for women intensified for life.