The Surprisingly Overlooked Detail About Edgar Allan Poe's Writing

Edgar Allen Poe famously wrote about madness, guilt, pestilence, decay, black cats and ravens, a dude getting bricked up alive in a wall (or immurement), another dude getting slowly guillotined to death across the stomach, and more. In many instances Poe's writing is thematically horrific, its descriptions lurid and disturbing, and its subject matter unnerving — but that's just the surface level. Those keen on Poe's work might notice a certain spooky thread of mystery winding through his tales. Secrets get unveiled, truths uncovered, and bit by bit the reader comes to some final realization about what's happening in the text. In other words, kind of like a detective story.

As many don't know, detective stories are exactly what Poe pioneered. Early in his career he wrote the ghost story "Ligeia" in 1838 and the well-known "The Fall of the House of Usher" in 1839. But before turning toward overt horror, Poe in 1841 released "The Murders in the Rue Morgue," which he called one of his "tales of ratiocination" — tales of reason and logic, per the National Parks Service. The story wasn't intended to be a "detective story" — those kinds of things didn't exist. Sherlock Holmes, the character, didn't show up in print until 1887, 46 years later. Agatha Christie's first novel, "The Mysterious Affair at Styles," was released in 1920, 33 years after Holmes. And all of our modern police procedurals didn't crop up until the 1950s. It was Edgar Allen Poe who launched the entire genre of detection fiction.

The very first detective story

It's important to note that Edgar Allen Poe wrote during what's been dubbed the "American Romantic" period. In these years — roughly 1830 to the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865 — none of our modern literary genres existed. No one was perusing shelves at a local Barnes & Noble and looking for the latest eye-catching young adult novel cover. In fact, Poe was so ahead of the curve that in addition to pioneering the detective novel and some gloriously macabre fiction, he was also arguably the "architect" of the modern short story, itself (per Poets.org). Bear in mind that the "novel," as a type of book, didn't exist until 1605 with the publishing of "Don Quixote," less than 250 years before Poe wrote. During Poe's life there were no hard distinctions between novels and the kind of shorter stories that he wrote.

Not only did Poe pave the path for all subsequent gumshoes to poke through crime scene evidence and make deductions, he did it using the same kind of serialized detective character reflected in later persons like Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, all the way to Columbo and more. Poe's arch-crime-solver was Monsieur C. Auguste Dupin, who uses the aforementioned "ratiocination" (reason, logic, etc.) to figure out who murdered two women in 1841's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue." Poe wrote two more stories featuring Dupin in the lead role: 1842's "The Mystery of Marie Roget" and 1844's "The Purloined Letter."

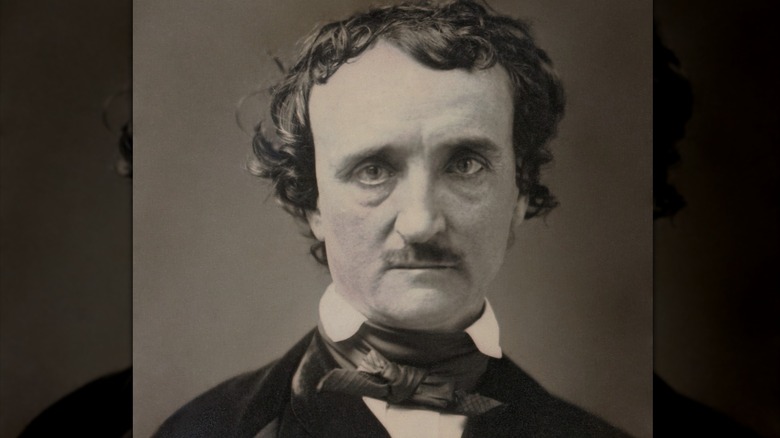

[Featured image by Unknown author via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

Playing fair with the reader

When we say that Edgar Allen Poe wrote the first "detective story," you might be wondering what he did differently from writers before him. As the aptly-named World's Best Detective, Crime, and Murder Mystery Books explains, in "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" Poe did two things that all other detective stories have done to be properly classified as such: "play fair" and "be readable."

"Playing fair" means recruiting the reader to solve the mystery along with the detective. This is part of the appeal of such stories whether readers or viewers realize it or not. The story needs to introduce all available clues to the audience — and not hide anything — so that the reader has a chance to figure things out, too. In "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" Poe not only did this, but did so through the narrator themselves, who plays the role of a sidekick in the story, like Holmes' Dr. Watson. In "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" the narrator meets the detective, C. Auguste Dupin. This allows Poe to explain things from Dupin to the narrator, who learns alongside the reader. If this doesn't sound like the most fundamental hallmark of detective fiction, few criteria would.

As far as being "readable" is concerned, an article in Studies in Popular Culture explains that "readable" means that a detective story must strive to be an excellent, understandable detective story, and just that. All other details and nuances come afterward.