Bizarre Attempts To Create The Perfect Society

It's an incredibly attractive idea, the establishment of a little slice of Heaven on Earth. Who wouldn't want to live in a utopian community, full of equality, happiness, and puppies, where every day is Taco Tuesday? How hard can it be? Apparently ... pretty hard. And really weird.

Rollestown

Right, so you're setting out to build your utopian community. Who do you bring with you? A mix of medical professionals, some farmers, some builders and construction workers, maybe? Or a bunch of thieves, pickpockets, and prostitutes? If you think the latter sounds like a great idea, then congratulations, you think like Denys Rolle.

Rolle was an 18th century English landowner, and he had the brilliant idea to build a utopian society in Florida. Since he was feeling particularly generous, he decided he was going to choose his original colonists from people who were rotting away in London jails. Those were, sadly, less than cream-of-the-crop type people, but one minor detail shouldn't stand in the way of a stellar plan.

Rolle started with 49 men and women and shipped them off to Florida and the St. Johns River, where they found nothing but mosquitoes waiting for them. Not only were there no homes, but Rolle insisted that before they built their own homes, they needed to dig up some palmetto roots for him. They said no, so Rolle took away their food. They left, as would we if some jerk took away our food.

The unwilling settlers fled to a nearby town to lodge a formal complaint and seriously, who can blame them? Arbitrators came to an agreement where the settlers would return if Rolle would stop being such a mean-spirited jerk, but once you set a tone like that, it's really, really hard to go back. Not everyone wanted to stay, and Rolle had to keep bringing over more people to replace the ones that chose to try their luck with the alligators, rather than him. Rolle eventually made the mistake of falling in love with one of his settlers, who (unsurprisingly) left him, probably after he took away her food.

The colony was almost non-existent by the 1770s, and Rolle had brief success restocking his plantation with slaves acquired the old-fashioned way, but it wasn't long after that Florida became Spanish territory and Rolle was given seven months to get out of Dodge. No one was heartbroken except for Rolle, who demanded restitution from England and got enough out of the deal that he could retire. The only people who made out in this story are Rolle and, presumably, the hungry alligators.

Koreshan Unity Settlement

Florida is a weird place, and it used to be even weirder. The Koreshan Unity Settlement was founded in 1893, built around the idea of equality regardless of gender, reincarnation, a single, dual-natured God, communal living, and cellular cosmology. Sounds impressive, doesn't it? Sane, even. Until you find out that "cellular cosmology" means "the Hollow Earth theory."

The driving force behind the community was a man named Cyrus Teed, and he had a vision. A literal one. Teed was a doctor and actual scientist, and when he was mucking about with electricity, he managed to give himself a shock so powerful that he knocked himself out. While he was out, he claimed that he had been visited by a divine spirit, who told him it was up to him to redeem the human race.

Not one to back down from a challenge, he changed his name to Koresh and started recruiting people into his society. In the next few years, he got around 4,000 people to go along for the ride, believing that he had found the "vitellus of the great cosmogenic egg". That was a fancy way of saying that he'd found the planet's belly button, and it was somewhere near Ft. Myers, Florida. It was important they settle there, because that's where the Second Coming would happen.

Sadly, there was no Second Coming. Even though outsiders thought he was a nutcase, he still managed to head up a self-sufficient, sustainable community that even supplied other area towns with electricity. He died in 1908 and definitely wasn't resurrected, even though his followers patiently waited to bury his body ... just in case. The last few residents were still there in the 1960s, although thankfully for everybody's sense of smell, Teed had been buried by then.

Pullman

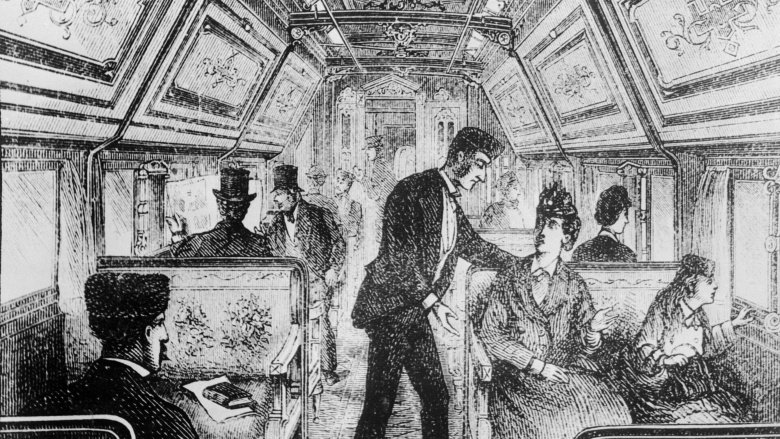

Pullman, Illinois was named for founder George Pullman. He built his community just outside of Chicago in the 1880s, intending it to provide the employees of his Pullman Palace Car Company with everything they could possibly need in one convenient place. That was so they never had to leave ... ever, ever again.

See where we're going? Pullman marketed his community as a feat of engineering, science, and art. It was the best of the best, and only for his employees. He insisted on the best for those that bought his company's train cars, after all, so why would he not want the same for his employees? There was, of course, a catch. Pullman believed that his workers were essentially uneducated heathens, who needed to be taught to enjoy the finer things in life and to appreciate everything capitalism had to offer. (Mostly, what it offered him.) That meant the community was laid out in such a way that the better areas were reserved for the higher-ups, and the unwashed masses were restricted to another area. Oh, if you were black? You couldn't live there at all.

You also needed to pay the insanely high prices charged by Pullman's store, pay another fee if you wanted to use the library, and attend the town's single church, no matter what your faith. Given that the workers were a diverse group of European immigrants, that didn't go over well. Did we mention there was no alcohol allowed? And the spies, too, that Pullman employed to make sure everyone was doing exactly what they were told and nothing more. This no longer sounds like a party we'd like to attend.

When the economy crashed in 1893, the whole house of cards came crashing down. No one was allowed to own their own home in Pullman, and even though he was forced to cut employee pay, he didn't cut the prices they were paying him for literally everything. Rioting spelled the end for Pullman in short order.

Germania

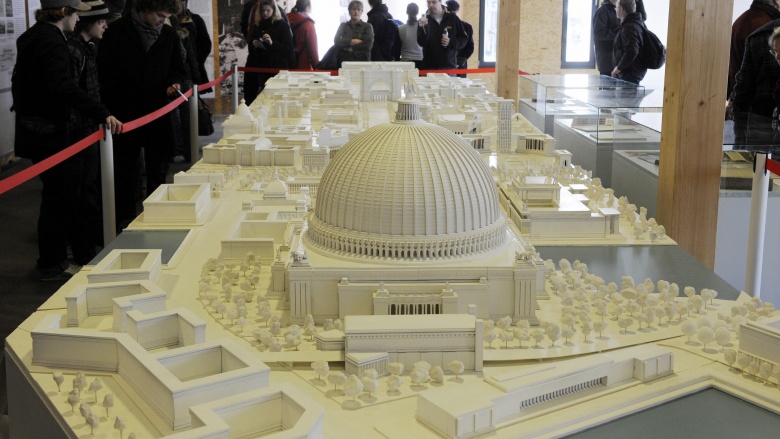

If Pullman's empire sounded like it should be run by a Nazi Fuhrer, what would the perfect society of an actual Nazi Fuhrer look like? We can still see a piece of it today, in Berlin.

The building is called the Schwerbelastungskorper, and we don't know how to pronounce it, either. It was the first building erected at the start of Hitler's grand plans to completely redesign Berlin as a tribute to Nazi glory, a city that would be organized around a road called the Boulevard of Splendor and the Volkshalle, a "people's hall" 16 times larger than St. Peter's Basilica. The Volkshalle, architect Albert Speer wrote, would be for the public adoration and worship of Hitler. The building was so huge, test structures needed to be built to see if the marshy ground could hold the weight, and that test structure was the Schwerbelastungskorper.

The building of Germania was well under way even before the end of the war, and Hitler had started planning it as early as 1926. Concentration camps were located near quarries to put prisoners to work digging stone or building bricks for Berlin's redesign. So much stone and brick was needed, Berlin even stripped its own streets of citizens deemed less-than-desirable, sending them to the camps to dig up all the raw materials they could find. The entire project was meant to show off the might of the Nazi empire and pay homage to its leader ... and we all know why that never came to fruition.

Fruitlands

Fans of a certain type of literature will be familiar with Louisa May Alcott, who wrote Little Women. She also spent six months of her childhood as a part of one of the most poorly thought-out utopian communities on the planet. She was 10 years old when her father, Bronson Alcott, took the family on the adventure of a lifetime. They set up Fruitlands as a transcendentalist community just outside of Concord, Massachusetts, starting their endeavor in June 1843. By January '44, they had moved right back out again.

On paper, it sounded like a noble idea. Fruitlands championed principles like harmony with nature, doing no harm to any other living thing, abolitionism, and sort of a general goodness. There were drawbacks, though, that started with that whole "no harm to anything" bit. They were so hardcore, their diet was restricted to things that didn't give up their "life force," like fruit trees that could keep producing. Unfortunately, the property they picked didn't have many fruit trees at all, and that seems like a pretty big oversight.

They also weren't allowed to use candles (because of the animal fat), which meant working and reading hours were severely limited as summer turned to winter. Things life coffee, tea, butter, rice, milk, and eggs were also off-limits, and it turned out that planting things created a bit of a moral dilemma for Alcott. That required disturbing the worms, after all, and clearly you can't have that.

Only 11 people joined the community, including one man who couldn't cope with the idea of physical work, and another who couldn't speak without swearing because he believed it elevated his pure spirit. Another disapproved of clothes. We can't imagine why this one failed.

Ralahine

The "luck of the Irish" is probably the most ironic idea ever, and in the 1830s, that luck struck with a vengeance.

A group of County Clare men and women got together to form the Ralahine Commune, a communal society on the estate of John Vandeleur. He wanted everything to go right, and even brought in consultants from overseas to figure out how to make this work. The community had 29 people, who paid him rent with the idea that they'd eventually use that to buy the land. They earned labor notes as they worked, which they used to "buy" the goods their neighbors produced. If they needed to, they could exchange the notes for normal, outside-world money. Alcohol, gambling and tobacco were banned. The community did so well, it started introducing entirely new machinery to the country. Life was good! In 19th century Ireland! This ... won't last long, will it?

Nope. Remember how we mentioned gambling was banned? Well, not everyone got the memo, and the commune was forcibly dissolved when Vandeleur (who had, presumably wrote the rules himself) decided to take a "do as I say, not as I do" approach to leadership. He lost the entire estate gambling, and when the commune met for the last time in 1833, they wrote of the "contentment, peace and happiness" they had found there. Way to go, Vandeleur.

Oneida Community

The 300-odd members of the Oneida Community took communal living to a whole new level, and shared a 93,000-square-foot house they called "Mansion House." Given some of their beliefs, this was probably a convenient arrangement that made sure no one's Walk of Shame was too long.

The basis of communal beliefs was that the Second Coming had already happened, and now it was humanity's turn to prove how good they were, and bring about Heaven on Earth. They did it by subscribing to a lifestyle that included the absolute adherence to the teachings of leader John Humphrey Noyes (who had already been deemed perfect by The Man Upstairs).

A huge part of what they thought God thoroughly approved of was variety, and that extended to marriage, too. The group practiced something called communal marriage, where every man and woman was connected in one big divine marriage. That not only meant two or three different partners a week, but that older community members often initiated younger ones into that particular way of life. What if you found "The One" and wanted to just stay with that person? You were considered idolatrous.

It's no surprise that this contributed in large part to the downfall of the community, but pieces of it are still around. Hard work was an essential part of the community, and among the businesses they founded was a silverware manufacturing company that's still the world's largest, even today.

Home

No, not your home. Just Home. The aptly-named Home was founded in 1896, on a peninsula that juts out into Puget Sound, Washington State. Originally, it wasn't entirely founded as a a utopian society, but rather the opposite. The founders and first members were anarchists, people who didn't fit into mainstream society for one reason or another, and resented being told what to do. What could possibly go wrong?

The founders tried to set the community up for success, building it on a foundation of few rules and quite a lot of hope. Land was held in trust and interested parties could buy into it, and there were a lot of interesting parties. There was a Professor Thompson, a cross-dresser who gave regular lectures on the virtues of women's clothes. There was Jay Fox, one-time railway man who was eventually arrested in connection with the assassination of President McKinley. And then there was Lois Waisbrooker, advocate of free love and women's rights long before feminism was ever a thing.

The community was first targeted for its anarchist label when McKinley's assassin labeled himself an anarchist, but for all their bluster, the Puget Sound group was far from violent. That wasn't the end of it, though, and it was Fox who struck the first death blow for the community. Fox wrote for, and ran, a community newspaper called The Agitator, and in 1911 he penned a piece called "The Nude and the Prudes," about the ongoing conflict between the people who thought skinny-dipping in the nearby bay was cool, and those that didn't want to be seeing any of what their neighbors had on display.

The real end came after the community was completely polarized. They gave people control over their own lands (and the ability to sell them), rather than holding everything in a communal trust. That led to some people selling their land to less-than-desirable neighbors just out of spite which, honestly, is what we'd do if someone got lippy about our skinny-dipping.

People's Temple

Everyone knows how the People's Temple ended: with a mass suicide at Jonestown. But long before that, Jim Jones had planted the roots of his perfect religious society in Indianapolis, Indiana. He moved there after marrying, stumbling on the bizarre idea of selling imported monkeys, to raise money to support his new community of believers. At the time, it wasn't the fire-and-brimstone preaching he'd be most famous for. That came later.

His followers settled into the People's Temple Full Gospel Church, attending services, faith healings, and performances on a theatrical level. Because this story can't get too weird, they eventually needed to expand, and settled into an old synagogue, leased to them by one of the area's most vocal opponents of fringe groups and generally terrifying cults.

Originally, the community was built on ideas we can all get behind, like community service, racial equality, and helping the elderly and the disabled. He was even appointed as head of the Human Rights Commission in Indianapolis because, why not? But things started getting a little squirrely when Jones insisted that everyone call him "Dad" and spend holidays at his church. That's when he started preaching that he had seen a vision of nuclear war, and they all needed to get the heck out of the area. That's why they headed south of the border and farther south still, and we all know what happened next.

Fordlandia

In the 1920s, Henry Ford's companies were so successful, he was using a huge percentage of the country's rubber. Deciding to cut out the middleman and start up production for himself, he sent 6,000 employees and a caravan of supplies to the Brazilian Amazon, and told them to set up shop and start producing. At a glance, it wasn't a bad deal. There were things like swimming pools and homes with conveniences like running water and electricity, but there were also things like ... mandatory square dances. If that's not a sign of a deranged mind, we're not sure what is.

Also, if you're wondering why Ford chose Brazil for his rubber plantation instead of Southeast Asia like everyone else, we're not sure. It's probably something he should have looked into, but it wasn't long before another big mistake became clear: He hadn't sent actual farmers or botanists along for the ride.

Ford's 6,000 workers started to get fed up with life in the Amazon, and with Ford's rules about things like no alcohol and no lady-of-the-night-friends. (Also, we're pretty sure the square-dancing was irking them, too.) Fortunately, there was an island in a nearby river that was quickly set up as a sort of jungle pleasuredome. They called it the Island of Innocence, because one of the things they had brought along was a sense of hilarious irony.

Ford tried relocating Fordlandia to better soil a few miles away, but the whole thing fell apart when someone solved the rubber problem a different way: by inventing synthetic rubber. Way to miss the obvious solution, Mr. Ford.