Reasons It Would Suck To Be A Pro Baseball Player

Being a Major League Baseball player can be pretty awesome. Not only do they get paid very well for playing a kids' game, but they get cheered for a good day on the job. (Wouldn't we love to get a standing ovation for working on a Saturday to finish the TPS report?) But as glamorous and exciting as their lives are, there are some downsides to being a ballplayer.

Minor league, minor pay, major BS

Major League Baseball players have longer careers and make more money than football players. They have a strong union and great benefits once they make it to the majors. Playing just one single day in MLB gets them full health care coverage for the rest of their lives. Just 43 days in the majors gets them into the pension plan. The biggest problem is all of the years it takes to get there. Even the best players are going to need several years of seasoning in the minor leagues. And just 10 percent of minor leaguers ever make it to the show.

Minor league life can mean not just long bus trips but extremely low salaries. "Minor league baseball players don't get paid for spring training," USA Today notes, even if they're up with the big-league club. The minimum salary is just $1,100 a month, and they don't get overtime, even though they put in many hours between games and practices. So there's currently a lawsuit on this issue to get the minors to follow the Fair Labor Standards Act.

So yes, some of those minor leaguers who didn't get big signing bonuses are literally making less money than burger flippers. Many of the players rely a lot on the $25 a day per diem they get on road trips. It seems ridiculous, given the big money in the MLB. As USA Today calculates it, "A major league organization with 250 players in its minor league system could give every single one of them a $30,000 annual pay spike for a total of $7.5 million, or roughly the cost of a decent fourth outfielder on the free-agent market." If they can't or won't do that, at least they should comply with the FLSA rules other businesses do.

It's expensive as hell to be a kid playing baseball

Not only does youth baseball require much more equipment than, say, basketball, but the advent of travel teams and specialized coaching for kids means it's harder than ever for a player from a poor or even middle-class family to have a shot at the majors. It's one of the reasons fewer than 7 percent of all MLB players these days are African-American.

"Baseball used to be the sport where all you needed was a stick and a ball. It used to be a way out for poor kids," Andrew McCutchen, star outfielder from the Pittsburgh Pirates, said in The Players' Tribune. "Now it's a sport that increasingly freezes out kids whose parents don't have the income to finance the travel baseball circuit."

These for-profit leagues that have a more elite level of play, and put players from different towns together to play in tournaments against other youth teams, are increasingly prevalent. And expensive. The Undefeated described it this way: "Over the past 20 years, youth baseball in America has become an endless flow of kids with $300 bats slung into $100 bat bags carrying $100 shoes walking into weekend tournaments that charge roughly $100 a kid to play and $10 a head to watch."

And it's harder for good players to get noticed by scouts unless they play in these tournaments. McCutchen, who came from a working-class African-American family, was one of the lucky ones. He was fortunate enough to have coaches as well as other families who helped pay for him to be on the travel teams. He may not have made it otherwise. And even then, McCutchen admits he may have chosen football over baseball because of "economics." But an ACL injury as a teen put an end to his NFL dreams.

In recent years, MLB started the Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities (RBI) initiative to help poorer kids play baseball. But it's not enough. MLB is losing good players to other sports because of money.

The unwritten rules are ridiculous

In a game with so many rules, it seems ridiculous that there are unwritten ones as well in baseball. And we're not talking about how responding with a "k" text message to a long, heartfelt message is a sick burn. Pretty much everyone can agree on the implications of that.

With baseball, there are at least two sides to every unwritten rule. Take, for example, theatrics after a home run like the bat flip. Toronto Blue Jays star Jose Bautista got grief (and ultimately ended up getting punched in the jaw the following year by Texas Rangers second baseman Rougned Odor) for doing a bat flip after hitting a massive homer against the Rangers to win a playoff series.

Meanwhile, Boston Red Sox designated hitter "David Ortiz does the same bat flip after every home run," as Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Brandon McCarthy put it. "He carries a Mariachi band around the bases with him every time he hits one. But it's okay because he's Big Papi." It's one thing to have an unwritten rule that bat flips should only be reserved for big moments. It's another thing to say that they're fine for Big Papi but not other sluggers.

Maybe the enforcement of these unwritten rules, with retaliation in the form of beanballs and harsh slides and the like, will change someday. Washington Nationals star Bryce Harper thinks it makes baseball "a tired sport, because you can't express yourself." His opinion is that he's fine with both the home run celebrations and the on-the-mound ones. "If a guy pumps his fist at me on the mound, I'm going to go, 'Yeah, you got me," he told ESPN the Magazine. "Good for you. Hopefully I get you next time.'" It will take a critical mass of more players with attitudes like him to change things, though.

You could be a target of kidnappers or have to pay off smugglers

Over 27 percent of MLB players are Latino, and many were born in other countries like the Dominican Republic and Venezuela. And they face a whole set of new problems when they make it and go back in the off-season to see their families.

"Some come from poor barrios and they're seen with envy," MLB investigator Joel Rengifo Añez explained to The Washington Post. "Why? Because they have a car with the big stereo system and so those who cannot get ahead see them with envy."

And in extreme cases, that can mean being kidnapped. That's what happened to native Venezuelan Wilson Ramos, then with the Washington Nationals. The catcher was kidnapped in 2011 and was rescued after 50 hours. Pretty scary stuff. And in 2005, the mother of Detroit Tigers pitcher Ugueth Urbina was kidnapped for five months in Venezuela before being rescued. The kidnappers demanded $6 million in ransom. Maura Villarreal said, "The most hurtful thing was having to bear them saying that my son didn't love me because he didn't pay."

That's not the only issue international players can face. If they're from Cuba and want to make their way to the United States for baseball, they might have to pay smugglers for the privilege. ESPN's Outside the Lines reported that future stars have "come to rely on a clandestine group of operatives" to get them out of Cuba and in front of MLB scouts. Take the case of Los Angeles Dodgers star Yasiel Puig. His Cuban escape was funded by a Miami man named Raul Pacheco, who Los Angeles magazine describes as a "small-time crook." The magazine said that "Pacheco had allegedly agreed to pay the smugglers $250,000 to get Puig out of Cuba. Puig, after signing a contract, would owe 20 percent of his future earnings to Pacheco." And people think Scott Boras is ruthless.

Players throw way too hard way too young

Tommy John surgery, in which an elbow ligament is replaced, is practically a rite of passage for young pitchers these days. For example, Yankee prospect James Kaprelian found out in 2017 that he needs it. Pitching coach Rick Peterson blames the way pitchers throw so hard and so much at such an early age in recent years.

And another drawback of travel teams is younger players are pitching in many more games, and at an earlier age, than in the past. The Washington Post writes that "to rise in rankings and win tournaments, some teams, especially in warm climates, play nearly year-round, competing in as many as 120 games per year, more than most minor league players."

Dr. James Andrews, the most famous surgeon doing this procedure, told USA Today that the biggest-growing number of pitchers coming to him for the surgery are high school kids. He said, "They outnumber the professionals. There was a tenfold increase in Tommy John at the high school/youth level in my practice since 2000. I'm doing far more of these procedures than I want to."

In addition, the physician readily admits that the procedure is not as successful on younger pitchers, "There's a higher failure rate than older pitchers because they're so young and just don't know how to get through the surgery," he shared. Getting surgery at any age can be fraught with peril. A teenager needing Tommy John surgery is pretty outrageous.

The lack of a salary cap if you don't play for a huge market

The National Football League has parity with its teams, thanks to salary caps. With MLB teams, it's a case of the haves and have-nots. Thanks to increased cable contracts, this is changing a little, and teams can sign some of their players long-term early. But there are still massive payroll differentials between teams like the New York Yankees versus small-market teams like the Tampa Bay Rays.

The top-spending teams have overall payrolls over $200 million, while the lowest-spending teams might be spending as little as $60 million. And when you look at the actual 25-man roster for the players currently on the team, versus those who have been released, injured, or traded to another team where the old team is paying the salary, you have the San Diego Padres paying just $29.4 million for their 2017 25-man roster. Since MLB has a $535,000 major league minimum salary, that means most players are making close to that amount. At just $4.5 million, Wil Myers is the team's highest-paid player.

Compare with the defending World Champion Chicago Cubs, the team with the highest 25-man payroll in baseball. They have 12 players who make more than Myers in 2017, most notably Jason Heyward at over $28 million. And Heyward had an awful 2016 in his first year with the team, batting just .230.

That's one of the benefits of being able to spend more—the ability to buy a player like Heyward and not have it prevent you from spending on other players, or from being able to compete. It can also help teams fill in gaps, like when the Cubs traded for Aroldis Chapman in 2016. The baseball haves can do a lot more than the have-nots.

The season is really long

At 162 games a year over six months, the Major League Baseball season is much longer than any other major professional sport. That doesn't even include the six weeks or so of spring training, or the month-long postseason. And these days, players are expected to stay in shape year-round, so they don't have a lot of downtime.

That means players are on the road and away from home for at least 81 days a year in the regular season, plus the aforementioned spring training and playoffs. And until the most recent labor agreement was ratified in 2016, some teams had to travel across the country after a night game to play a day game the next afternoon.

Those cross-country flights and having to fly multiple times in a week take their toll. And the grueling length of the season is relentless. It's why "greenies," or amphetamines, were used so often in MLB back in the day, especially when playing a day game after a night game. Yes, players, including future Hall of Famers, openly did speed to compete.

These days, greenies are banned, which is better for players' health. But it means they're more tired while playing. There has been talk in recent years about going back to the pre-expansion 154-game schedule, but nothing has come of it.

Players can get the yips

The word yips is originally a golf term that meant "a brain spasm that impairs the short game." In MLB, it's used to describe when a player can no longer do some routine thing, like throwing to first. It used to be called Steve Blass Disease, for the pitcher who could no longer throw strikes. Second basemen Steve Sax and Chuck Knoblauch each had it, where they could no longer throw to first without the ball going awry.

Sax conquered his issue, but Knoblauch never really did. He even accidentally hit Keith Olbermann's mother in the stands, then got switched to the outfield, and then was out of baseball. There appears to be a psychological component, and it could be neurological, too.

Some cases are more debilitating than others. Jon Lester has the yips when it comes to throwing to first base, but it really hasn't derailed his career.

Even talking about it is a huge taboo in baseball. Dodgers pitcher Brandon McCarthy experienced the yips after coming back from Tommy John surgery in 2016. He was one of the rare players to talk in public about this after he got over it. Orel Hershiser, the team's pitching coach, gave McCarthy credit for his candor, and said that he still has never discussed with old teammate Sax when that player had the yips.

Only players get punished for steroids

Slugger Barry Bonds may have seven MVP Awards, and pitcher Roger Clemens may have seven Cy Young Awards, but the only way they're going to get into the Baseball Hall of Fame in the near future is if they buy the ticket. That's because both reportedly used steroids to give them an edge, and they're not the only ones from the Steroid Era who are on the outside looking in.

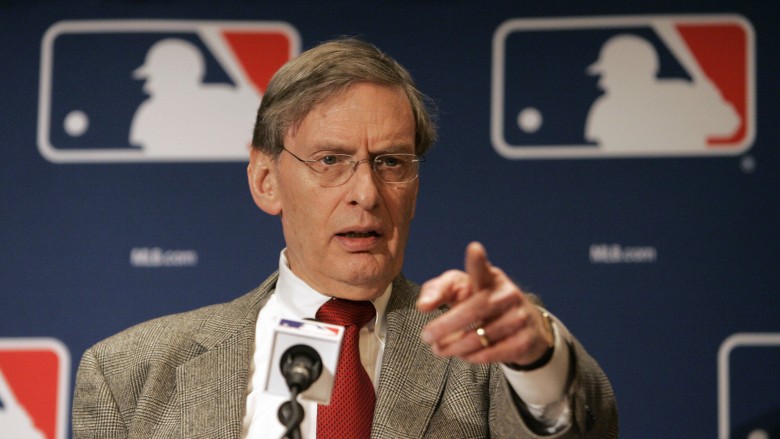

Meanwhile, Bud Selig, the MLB Commissioner who presided over this era, got elected to the Hall of Fame in late 2016. And legendary managers Joe Torre, Bobby Cox, and Tony LaRussa all got elected to the Hall of Fame the same year. So the commissioner and the three most successful managers during the Steroid Era make it in, while the two top players, one of whom helped Torre get two of his four rings, don't. Not to mention all the other reported performance-enhancing drug users, whether publicly named or not, who helped these managers win (Mitchell Report names Andy Pettitte, Mark McGwire, and David Justice).

Are people supposed to believe these managers, who were around for decades and certainly saw more players up close than fans would ever have a chance to, had no idea that performance-enhancing drugs were being used? Or that Selig had no idea what was going on? That doesn't pass the smell test.

A growing number of baseball writers who vote the players in are starting to notice this discrepancy, too, which is why Bonds and Clemens received more votes for the HOF in 2017 than they ever had before.

The fact is that players take all the risk when it comes to PEDs. They face the health issues and potential repercussions like loss of salary and reputation. Meanwhile, the commissioners, managers, and owners who benefited from this use still get to reap the benefits.

Want to really put an end to PED use in baseball? Start punishing teams beyond them losing a player from PED use. Maybe big fines, or vacating wins, or even removing titles, or leaving the whole team out of the Hall of Fame might get their attention. If people besides players had gotten the hammer on them in some way, things truly would have changed a long time ago.