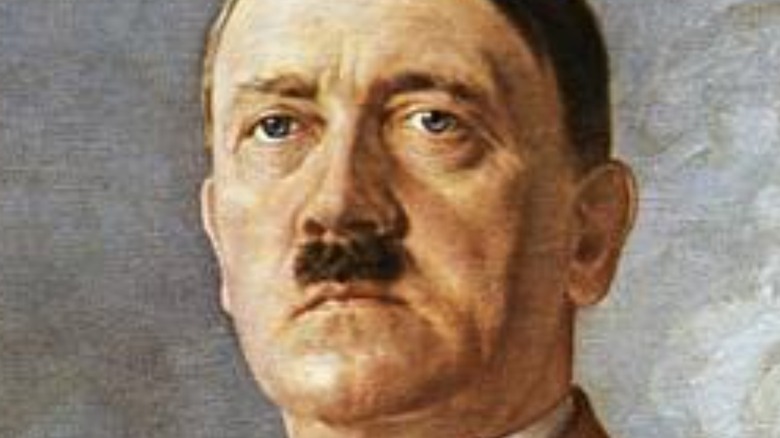

These Notable People Were Born On The Same Day As Hitler

It's always fun to find out someone shares your birthday. It's even more exciting when it's not just the same date, but the same year. Birthday twins! And who hasn't bragged about sharing a birthday with a celebrity, even though we all know that being born on the same day required no effort on our part.

The problem is, terrible people have birthdays too. It's easy to want to write off a date because someone evil was born on that day, but then all their innocent birthday twins have to suffer as well. And who would be the absolute worst person to share a birthday with? The same person you can't share a mustache with: Adolph Hitler.

April 20, 1889 will forever be famous as the day one of the most evil men in history entered the world, and the day all our time traveling descendants will be aiming for when they go back in time to kill baby Hitler. But plenty of other people were born within hours of the future-Fuhrer, and almost none of them come anywhere close to how terrible he was. They became famous or notable for a wide variety of occupations, from a politician and an athlete to a mystic and an anarchist. They might not be household names like their genocidal birthday twin, but then who is? Here are notable people who share Hitler's exact birthday, down to the year, and how the timelines of their lives compared with his.

Dr. Stuart W. 'Tack' Harrington

Stuart Harrington, known as "Tack," was one of the early 20th century's most groundbreaking surgeons. He worked at the prestigious Mayo Clinic for 34 years, according to his profile on the Mayo Clinic's official website. He was soon a "famous surgeon" and an "international authority." He pioneered many techniques and treatments, all of which are very complicated and medical sounding, but the list is long, and includes breakthrough work on lung, spinal, and breast surgeries. A workaholic, the surgeon's only hobby was going for drives to break up his crazy long shifts. Yet he also had an excellent bedside manner, known for showing exceptional "sincerity and concern" for all his patients.

Tack Harrington was able to go on to such an esteemed career in medicine because he first got into an incredible college, Pennsylvania State University, as a pre-med student in 1908. He excelled in school, managing both his coursework and playing for the varsity football teams at both Penn State and later at the University of Pennsylvania. All this, despite the fact that Harrington had to hold down multiple jobs to pay his tuition, since his father disagreed with his decision to pursue medicine. His college experience obviously laid the groundwork for his success and drive to help others.

The same year Tack Harrington was accepted to Penn State, the World History Project says Adolph Hitler was rejected from the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Twice. That also set him down the path that would make him infamous. Others have said it before, but seriously, think what could have been avoided if Hitler was a little better at painting.

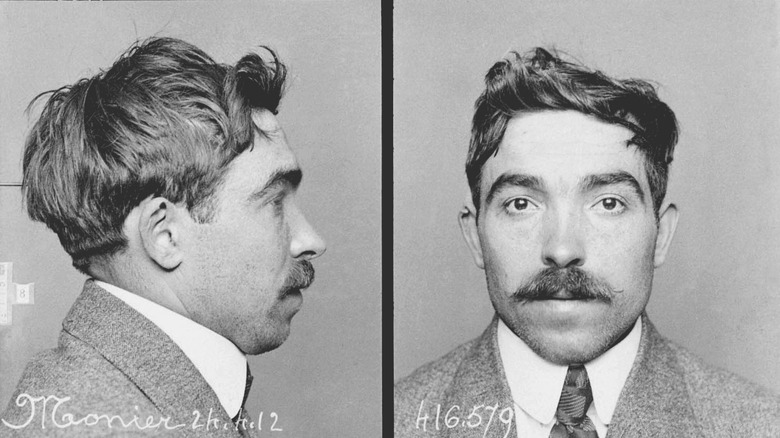

Étienne Monier

Étienne Monier, who went by Elie, was born in southern France. Before long, he was getting into trouble. According to "The Bonnot Gang: The Story of The French Illegalists" (via the Anarchist Library) by the time he was 16 the police were keeping an eye on him, since he'd been accused of theft and convicted of assault, plus they didn't like the people he hung out with or his anarchist principles. In 1909, Monier dodged the draft and fled France. He was only able to return after using a friend's identity.

Already living outside societal norms, it made sense that Monier fell in with the Bonnet Gang, which was not so much a loyal group as "a union of egoists associated for a common purpose." The purposes included armed robbery, and soon Monier took part in a bank heist where three cashiers were killed. The law eventually caught up with the gang, and Monier was sentenced to death by guillotine in 1913. In his last will and testament, he wrote, "I leave to society my ardent desire that one day, not far off, a maximum of comfort and independence will prevail in the provision of social needs, so that in one's leisure time an individual may be better able to devote himself to whatever makes life more beautiful." He also left his revolver to a museum, on the condition they inscribe it with "Thou shalt not kill."

According to the Holocaust Encyclopedia, one month after Monier was executed (which, incidentally, was on April 21, one day after their shared birthday), Hitler left his homeland of Austria, moving to Germany for the first time.

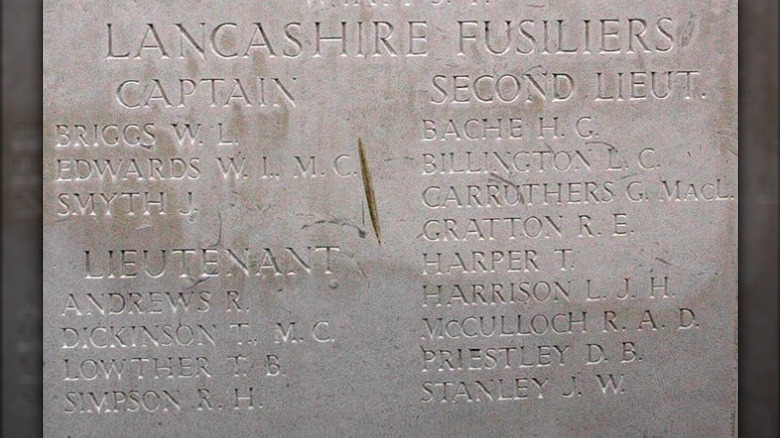

Harold Bache

Harold Bache was born into that level of English privilege where everything was going to go right for him. His father was a successful lawyer, and Bache was accepted to the private King Edward's School. After graduation, he attended Cambridge University. Throughout his schooling, everyone noticed he was a great guy but even greater at sports. The school magazine called him "a boy of great character and a notable athlete." "A History of Eton Fives" (via the Eton Fives Association) says he played four different sports at Cambridge.

Bach went on to play both professional cricket and professional soccer, scoring 87 goals in 39 games. He also competed in tennis at Wimbledon. But when WWI broke out, Bache left his cushy life behind and enlisted. Author Simon Wight (via Remember the Fallen) says Bache routinely showed uncommon amounts of bravery at the front, on one occasion refusing a direct order to take cover in order to rescue some of his comrades, and on another he was seen "walking about the trenches, pulling the wounded out of danger, encouraging his men and binding up wounds, every moment in peril of his life." Harold Bache's luck ran out on February 16, 1916, when he was shot by a German sniper and died.

Adolph Hitler also served in WWI, and War History Online reports that he was also gravely wounded in 1916, barely 60 miles from where Bache was killed. Had his shrapnel wound, which landed him in the hospital for two months, been as deadly as the snipper who trained his sight on Harold Bache, the history of the 20th century might have been very different.

Prince Erik, Duke of Västmanland

The 1918 pandemic became known, unfairly, as the Spanish flu. But one of the first people to come down with it in that country proved how it could strike anyone: King Alfonso XIII. While he would live, other royals in Europe would also fall ill and, according to Royal Central, one young prince would not be so lucky.

Prince Erik of Sweden was the youngest son of Gustav V, the Swedish Royal Court explains. Even before the pandemic, he didn't mix with outsiders much, because he'd been born with epilepsy and a "mild learning disability," possibly due to medication his mother had taken while pregnant with him. Yet even living this "extremely secluded life," he still managed to contract the flu in the summer of 1918. He died on September 20, with only his brother Prince Wilhelm by his side.

Adolph Hitler did not contract the 1918 flu that killed Prince Erik and so many others. In fact, the pandemic might be the best thing that ever happened to him. According to a (slightly controversial) paper by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (via Politico), the effects of the deadly flu were felt long after millions died. The paper posits that the societal changes caused by the upheaval of people's lives actually "correlated with an increase in the share of votes won by right-wing extremists, such as the National Socialist Workers Party." This, so the theory goes, directly led to the Nazi party's increased power, which eventually got Hitler appointed chancellor of German, at which point he was poised to take over.

A.J. Balaban

If you've ever seen a movie in a theatre, you owe most of that experience to Abraham J. Balaban. He essentially created the experience in the beginning of the 20th century. Someone had to, since movies were brand new and there was no automatic understanding about what watching a movie entailed. A profile on Balaban in Variety in 1929 managed to call him a "pioneer" in the industry four times in the first two sentences. He was a big deal.

He got his start in the business with his family, running and leasing vaudeville theatres in Chicago. Early success led to them building what was the biggest theatre in the city, called the Central Park, in 1915. But in 1921, Balaban opened the theatre that is still a landmark today, calling it simply, The Chicago. Described by Madison Square Garden Entertainment as a "miniature Versailles" that "leaves its visitors breathless," the Chicago was not just the best theatre in existence – when it opened it was called "the Wonder Theatre of the World" – but it became "the prototype for all others." Every theatre after that wanted to be like the Chicago and give its patrons the same type of movie-going experience. Balaban was the vanguard of the most important part of the entertainment industry: the experience of the people being entertained.

Three months before Abe Balaban opened the Chicago, the theatre that would be his legacy, Adolph Hitler was made the head of the Nazi party and given the title of Führer. That, too, would make his legacy.

Walter Costello

When you think of ganglands, St. Louis probably doesn't come to mind. It's certainly no New York or Chicago. But at the turn of the 20th century, there were incredibly powerful gangs in the city. According to "Egan's Rats: The Untold Story of the Prohibition-Era Gang That Ruled St. Louis," the head of the titular gang, Tom Egan once told a newspaper reporter that while sure, his people committed murder, "We never shoot unless we know who is present."

One person who was often present in the early 1900s was Walter Costello, one of the Rat's tough guys. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch records (via historian Ken Zimmerman Jr.) that St. Louis was so corrupt at that point, Costello was a gang member and murderer, but he was also one of the city's deputy constables. He didn't worry about upholding the law, instead making brawling – and, routinely, almost dying – in bars and taverns his specialty. Amazingly, he survived multiple stabbings and shootings he received in these bar fights. At least, he did until 1917. In yet another brawl, started because he refused to leave, he was shot by two police officers and died.

Like Walter Costello, Adolph Hitler knew if you were part of a violent gang and wanted a fight, you went to a bar. Six years after Costello was killed, Hitler and the Nazis attempted to take over the German government by starting a fight in a Munich beer hall. He and his thugs burst in, and Hitler fired shots into the air, declaring a "national revolution," per History. The Beer Hall Putsch failed, probably because Hitler left early that night. Costello should have done the same.

Marie-Antoinette de Geuser

Marie-Antoinette de Geuser, also known as Marie of the Trinity, was called to a religious life from a young age. In one letter she wrote of a mystic experience: "In this state, it seemed that my 'self' was dead, and that God alone remained: it was somewhat as if His Unity, His Immensity, and even, I know not how, His Changelessness were subsisting within me. It was God alone and nothing of myself remained." Marie wanted to join the Carmelite order and become a nun but was too sickly. So she became a kind of unofficial nun on her own, writing down her mystic experiences. After she died in 1918, her letters were turned into a book, "Consummata," and it became a sensation, with multiple updated versions released throughout the 1920s. One reviewer said Marie would "almost certainly take her place one day among the foremost of the mystics of her time," another said "it would be impossible to find greater spiritual depth and soundness of doctrine."

Edith Stein, who was born Jewish, converted, and became a Carmelite nun (and eventually a saint), was a big fan of Marie. She wrote that Marie "had to undertake this highest Christian duty in the midst of the world." Saint Edith Stein is even said to have had Marie's book with her when she fled the Nazis in 1938.

As for the one making her do the fleeing, the 1920s saw Hitler's own publication. Like Marie's, it was his thoughts and feelings condensed down and put on paper. "Mein Kampf," unfortunately, would fill people with as much hatred as "Consummata" filled people with faith and love.

Hubert Houldsworth

Hubert Houldsworth was a British lawyer and Member of Parliament, who went on to be Controller General at the Ministry of Fuel & Power from 1944 to 1945, and then chairman of the National Coal Board from 1951 to 1956. Sound boring? If only we had more politicians like him today. Houldsworth went all-in on supporting the coal unions, blocking various bills and regulations he felt would do the workers harm. While these included things that might be controversial today (like fighting to limit immigration from Europe, so the jobs in the mines would go to British people), even small things caught his attention. According to "Scottish Coal Miners in the Twentieth Century," in he wrote that he saw no problem with minors taking time out to perform plays, explaining he had "no hesitation in saying that community drama and other similar cultural activities do increase the output of coal in that they foster a spirit of healthy and happy cooperation."

This did not make Houldsworth popular in some areas. The conservative publication The Spectator (which decades later would have Boris Johnson as its editor-in-chief) complained about how Houldsworth was spoiling the miners: "The past eight years have seen the miners become the highest paid group in industry. They have been flattered and cajoled and given one concession after another."

Unlike Houldsworth, when Hitler had power after he took over Germany in 1933, he turned against unions with a vengeance. He immediately had their leaders beaten, arrested, tortured, and either jailed or sent to early versions of the concentration camps. The Encyclopedia Britannica says that his making trade unions illegal resulted in much lower wages across the county.

Albert Jean Amateau

Born in the then-Ottoman Empire (now Turkey), the American Jewish Archives sums up Albert Jean Amateau's busy life: he was a "social worker, lawyer, businessman, author," and after he moved to the United States, he served in WWI, where he was wounded. Back in New York City, he became the first rabbi to have a deaf congregation.

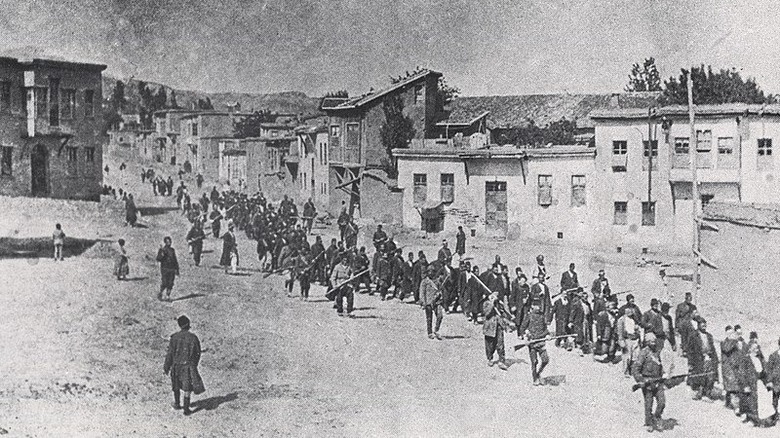

Hitler wouldn't be besties with this birthday twin, what with Amateau being Jewish and all, but weirdly, they both had very messed up opinions on the Armenian Genocide of 1915-22. A speech purportedly given by Hitler in 1939 defended Germany's invasion of Poland and the slaughter of innocent people, saying history would not judge them. He asked, "Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?" He was right; the world had already forgotten.

But 50 years after Hitler gave that speech, Amateau wanted everyone to know that Hitler had been wrong ... because the Armenian Genocide never happened. In a sworn statement to the U.S. Senate in 1989, he said: "One and a half million Armenians are claimed to have been massacred. The avowals of their leaders prior to and after the First World War prove that there had been no massacre ... If 1.5 million Armenians lost their lives during that war, they died as soldiers, fighting a war of their own choosing against the Ottoman Empire which had treated them decently and benignly ... A few thousand Armenians may have lost their lives during their relocation, caused by their own subversion."

At the start of the Armenian Genocide, this supposed expert witness hadn't lived in Turkey for six years. Congress would not officially recognize the atrocity until 2019.