The Insane True Story That Inspired 'The Fugitive'

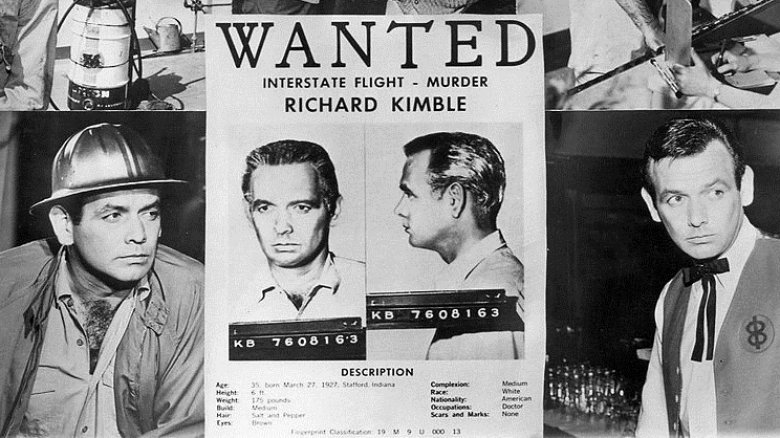

On August, 29, 1967, an unprecedented 78 million people huddled around their boob tubes to suck the milk of television greatness. For four years, fans of The Fugitive had followed Dr. Richard Kimble on his quest to exonerate himself by catching the one-armed man who killed his wife. Finally, his moment of truth had come, and viewers were salivating to see it. The ratings record set that night stayed unbeaten for 13 years. And after 13 more years everyone's favorite space fugitive, Han Solo, played Kimble on the big screen.

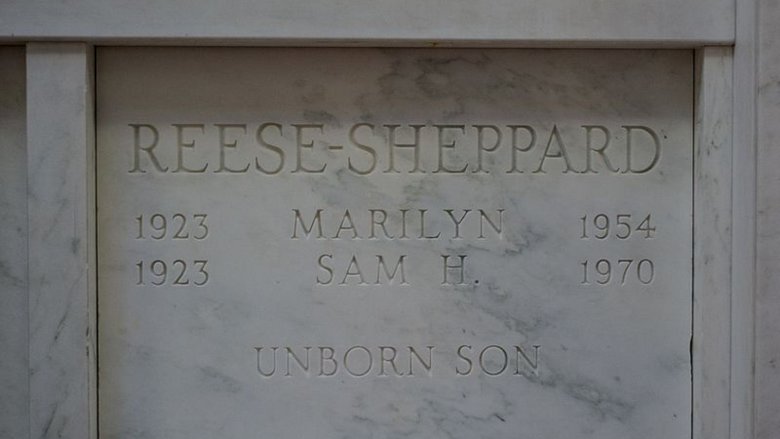

Kimble attained his happy ending by catching the elusive killer, thereby proving his innocence and providing viewers vicarious closure. The Fugitive's real-life incarnation, Dr. Sam Sheppard, wasn't so lucky. Like Kimble, Sheppard's life was marred by loss and accusations. But in many ways, his saga seems more fictive than bona fide fiction –- except for the ending, which feels real in all the wrong ways.

The early morning nightmare

On the night of July, 3, 1954, Sam Sheppard and his pregnant wife Marilyn entertained guests at their Cleveland, Ohio home. The festivities concluded around midnight, by which time Sam had passed out on a daybed. His wife retired to the upstairs. Documents compiled by Cleveland State University established that someone bludgeoned Marilyn Sheppard to death between 3:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m. Sam Sheppard would tell police that he awoke to his wife's final moments. Her screams had sent him sprinting to her aid, but a "bushy-haired" assailant knocked him unconscious. A second tussle with the intruder yielded more of the same.

The next time Sheppard opened his eyes, he was partly submerged in a lake. Drenched and disoriented, he called a pair of neighbors at around 5:50 a.m. to break the news of his wife's demise. Soon thereafter, a posse of police, reporters, friends, and family flooded the crime scene. Sheppard's 7-year-old son, meanwhile, lay asleep in his bed, completely unaware of the carnage that had transpired. Sheppard received medical attention for possible head trauma and incoherently related his version of events to authorities.

From there, the real doctor's path diverged drastically from his TV counterpart's. Sheppard didn't go on the lam or pursue the bushy-haired man. Instead, he stayed and faced his accusers in a trainwreck of a murder trial that derailed his life, killed his reputation, and cost him his freedom.

The case against Sam Sheppard

Sheppard's fate seemed sealed from the get-go. He didn't have the luxury of a camera crew to film the murder. There were no scriptwriters to steer his story in a positive direction. And he couldn't count on 1950s forensics to decisively determine his guilt or innocence. The doctor's fate depended on the strength of his words, the unbelieving ears of the public, and his own dubious actions.

In the immediate aftermath of the crime, Sheppard looked like a culprit trying to hide his blood-red hands. As the Washington Post detailed, for days the doctor deemed himself medically unfit for interrogation. Another physician backed that position, but it was Sheppard's older brother, Stephen. Sheppard additionally balked at requests to take a polygraph test or any kind of truth serum. Did he have something to hide? Unquestionably.

For three years, Sheppard had cavorted with nurse Susan Hayes. He dazzled her with gifts, and she gave him her heart. He then resolutely lied about his extramarital affair to authorities. But much to the doctor's dismay, Hayes didn't. She instantly became the linchpin of the prosecution's case, which alleged that Sheppard slayed his wife during a fight about Hayes.

Hayes was only one of several courtroom haymakers. Investigators had found what seemed to be Marilyn Sheppard's blood on her husband's watch. Moreover, the coroner implied in court that the murder weapon (which never surfaced) was a surgical tool. Predictably, the jury found Sheppard guilty and he received a life sentence.

Investigative bias galore

In fairness, there's far more to Sheppard's conviction than incriminating clues. Criminal investigators, for instance, had treated the doctor's guilt like a foregone conclusion. On one hand, that sounds fairly reasonable. Sheppard was the only obvious suspect in his wife's death and seemingly acted the part. Furthermore, he shot himself in the foot with a scandal-filled syringe by concealing his infidelity. On the other hand, it's hard to ensure justice when officials aren't interested in seeking it.

Court records revealed a slew of investigative improprieties. It seemed that Dr. Gerber, the coroner in the case, had actively sought to paint Sheppard as the killer. After inspecting the crime scene, he reportedly proclaimed, "Well, it is evident the doctor did this, so let's go get the confession out of him." Gerber then made the questionable choice to question Sheppard, who was sedated at the time, during a hospital examination.

The cops similarly wore their prejudice like a badge. Soon after the coroner cornered Sheppard, police swooped in. Officers repeatedly declared him guilty and urged him to confess straightaway. That could explain why Sheppard ducked other interrogations like a frightened boxer. He knew he was a walking bull's-eye. Even then, there were multiple occasions when he willingly met with detectives sans attorney.

The most blatant display of police bias occurred during the trial. Before Sheppard took the stand, law enforcement publicly branded him a "bare-faced liar." Clearly, justice wasn't blind; it just had tunnel vision.

The media run amok

If 1890s America suffered from yellow journalism, then 1954 Cleveland had severe journalistic jaundice. Local reporters rabidly attacked Sheppard and poisoned the public against him. In their ruthless rush to railroad him, they routinely twisted the truth like a Twizzler. The judge in Sheppard's murder trial magnified the mayhem, refusing to sequester the jury despite evidence of media influence. As a result, jurors had to base their verdict on facts presented in court and the falsehoods produced by the press.

A judge would later abjure that abhorrent reporting, citing an avalanche of spurious accusations and speculations. Newspapers falsely claimed that Sheppard had fathered a child with a prison inmate and portrayed him as a Hyde in Jekyll's clothing. Journalists didn't just recount testimony; they repurposed it to fit a nefarious narrative. They even altered an image from the crime scene, as the judge described, "to show more clearly an alleged imprint of a surgical instrument" on a bloody pillow. They might as well have written that the killer's name rhymed with "Ham Leopard."

The untoward onslaught tainted not just the jury, but the criminal investigation. Reporters conducted themselves like schoolyard instigators egging on a fight. One editorial practically dared authorities to arrest Sheppard, which they did the same night it was published. Another prompted the coroner to make an inquest. Throughout the case, pathologically bad reporting seemed to play just as big a role as the actual evidence, if not more so.

An appeal for justice

Media mudslinging and investigative unprofessionalism had created a show trial that became a sideshow. No judge worth their gavel would abide by such a debacle, and Sheppard knew it. But justice took its time and then some. Sheppard's second crack at court didn't come until 1963, the same year The Fugitive first aired on television. By then his father had died, a bestseller had been written about his case, and his son was approaching legal adulthood. Life had moved forward while Sheppard had languished in prison.

Forensic technology was also advancing. In the mid-1950s, bloodstain patterns generally had the analytical usefulness of Jackson Pollock paintings. But according to a PBS Nova broadcast, those inscrutable death flecks took on real meaning when viewed by scientists like Paul Kirk. Kirk was one of the trailblazers in blood splatter analysis and lent his expertise to the Sheppard case. After doing his own assessment, he concluded that Sheppard couldn't have caused the bloodstains observed at the crime scene, adding credence to Sheppard's intruder story.

Kirk's testimony played a pivotal role in Sheppard's retrial, as did the efforts of defense attorney and courtroom braggart F. Lee Bailey. (Most famously, Bailey would later successfully defend O.J. Simpson.) Bailey successfully demonstrated to an appeals court that media bias had blighted the 1954 criminal proceedings. And when a higher court overturned the appellate decision, he took the fight to the U.S. Supreme Court and won, finally securing a retrial in 1966. This time the gavel swung in Sheppard's favor.

Freed yet still unfree

In 1966, Sheppard won his freedom but had lost everything else. His personal life soon disintegrated like a sandcastle while his relationship with booze refused to ebb. The book Crimes and Trials of the Century discussed how F. Lee Bailey kept him off the witness stand due to Sheppard's drug and alcohol problems. Not even a second marriage from behind bars could save Sheppard from colliding headfirst with oblivion. He and his wife divorced in 1968, and malpractice lawsuits guaranteed he would never work in medicine again. The turmoil only plunged him deeper into darkness.

By comparison, Richard Kimble's days on the run sound heavenly. He only had to flee law enforcement. Sheppard sought to outpace his past, which had gotten a humongous head start. His son recalled in a Nova interview: "Dad couldn't live a regular life. He continued to be harassed. Dad couldn't work. He could hardly walk down the street. People would yell 'murderer, wife murderer' at him." Unable to find normalcy, the detested former doctor embraced his otherness by becoming a professional wrestler in 1969.

According to Sports Illustrated, Sheppard's foray into wrestling began with his third wife, Colleen Strickland. Strickland's father ran a wrestling promotion, which Sheppard joined. Performing under the name "Killer Sheppard," he wrestled 40 matches. (Notably, he invented a maneuver called the "mandibular marvel," which became the basis for legendary wrestler Mick Foley's "mandible claw.") In 1970, he died of liver disease.

A chance at vindication

After Sheppard was laid to rest, his son, Sam Reese Sheppard, remained restless. The younger Sheppard had watched his father wilt under the weight of public scorn, a permanent prisoner of perception. It was an ugly outcome for a handsome doctor who'd been wronged and ruined by the justice system. S.R. Sheppard couldn't undo the past, but he was determined to change how future generations viewed his father. To that end, he enlisted the help of modern science.

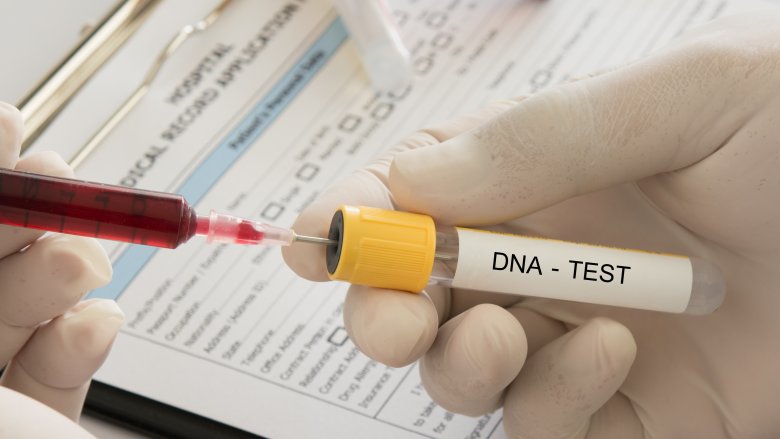

More than four decades after his father's murder conviction, S.R. employed a tool that didn't even exist until the 1980s: DNA profiling. As the LA Times elaborated, scientists compared DNA extracted from the late Sam Sheppard to genetic material collected from the 1954 crime scene. The results illustrated something that the departed doctor had consistently maintained: there had indeed been a third person present during Marilyn Sheppard's slaying.

Blood taken from a woodchip as well as a pair of Sam Sheppard's pants didn't match either Mr. or Mrs. Sheppard. Furthermore, genetic material discovered on Marilyn Sheppard's body suggested that the killer had sexually assaulted her. Crucially, that material matched the DNA of this mysterious third person. Suddenly, the once widely rejected account of the bushy-haired man seemed all too tenable. But if an unidentified intruder had committed the crime all along, who was it? As it turned out, S.R. Sheppard and defense attorney F. Lee Bailey had a possible culprit in mind.

The Richard Eberling theory

One of the DNA samples submitted for testing came from convicted murderer Richard Eberling, who had washed windows for the Sheppards. Per the LA Times, Eberling acknowledged working at the Sheppard residence close to the time of the 1954 murder. Curiously, he added an unsolicited detail, telling officers that he had cut his finger on a window. (A different Sheppard employee would later dispute this claim.) In retrospect, it sounds like a preemptive alibi.

In 1959, Eberling got busted for ripping off Sam Sheppard's brother, Richard. Among other items, he had stolen a ring from a clearly labeled box of Marilyn Sheppard's belongings. Interestingly, he isolated that item from everything else he took, as if assigning it special significance. None of these revelations would come to light until long after Sam Sheppard's death. Once Sam Reese Sheppard became privy to this incendiary info, he had a suspect to pursue, and pursue he did.

According to the Washington Post, Eberling vehemently denied the accusation in a 1996 interview, proclaiming: "Heavens no, I didn't do it. I don't even kill wasps in my own home. It's not my nature." Obviously, he would have made a terrible exterminator, but his track record with humans told a much more brutal story. In 1989, a jury convicted Eberling of the 1984 killing of his longtime employer Ethel Durkin, who died of blunt-force trauma. Two decades earlier, someone had mysteriously bludgeoned Durkin's sister to death.

Eberling's alleged confession

While genetic testing had seemingly absolved Sam Sheppard, it provided little clarity on Eberling's guilt. The Washington Post reported that the latter "shared a key genetic marker" with the presumed killer, but that connection proved inconclusive. Much like Sheppard before him, Eberling died shrouded in suspicion. However, one outspoken inmate claimed to know the truth.

According to self-professed confidante Robert Lee Parks, the window washer came clean about murdering Marilyn Sheppard before passing away. The Associated Press revealed that Parks brought this supposed admission to the attention of assistant Cuyahoga County prosecutor David Zimmerman and supplied a letter penned by Eberling himself. In it, the confessor shared blame with Sam Sheppard, writing that the doctor paid him a kingly sum of $1,500 to kill his pregnant wife.

It seemed that Eberling had provided not only a smoking gun, but also the bullet casings and a ballistics report. But it wasn't so simple. He had previously denied playing a role in Mrs. Sheppard's death. Worse, Parks offered two different versions of Eberling's story as if to cover his bases. The reddest flag of all was Parks' unexpected about-face. Not long after going public with Eberling's letter, the prisoner portrayed it as a ploy and personal favor. By providing a false confession, Parks claimed, Eberling would help him transfer to a new facility. Given the mishmash of motives and contradictions, it seems likely that Parks' bombshell was a dud.

The quest to clear Sheppard's name

Marilyn Sheppard's murder cost Sam Reese Sheppard both of his parents. But over the years an influx of evidence made one of those losses look avoidable. A media-driven witch hunt enhanced by judicial indifference had possibly put an innocent man behind bars and destroyed his will to live. Eager for retribution, S.R. Sheppard sought to rectify that travesty where it began: in court.

The LA Times reported that the defamed doctor's son sued to have him declared innocent. If successful, he would push for $2 million in compensation. Years of digging and reopening old wounds had culminated in a marathon of testimony and DNA discussion. Even F. Lee Bailey made an appearance. Would the public clear Sam Sheppard at last? No. There's a thick line between deeming someone definitely innocent and simply finding them not provably guilty in the eyes of the law. The jury declined to cross that line.

Ironically, F. Lee Bailey, who had fiercely fought to free Sam Sheppard, may have tanked the effort to restore his client's reputation. CBS explained that Bailey admitted to massaging facts and testimony in the past to make Richard Eberling appear guilty. At the very least, that eliminated a potential murder suspect. At worst, it fueled speculation that Sheppard got released on technicalities rather than truths. If there was ever any doubt that reality follows different rules than television, that doubt surely evaporated here. Sometimes there simply is no happy ending.

Did Sam Sheppard really inspire 'The Fugitive'?

You'd be hard-pressed to find anyone who doubts Sam Sheppard's influence on The Fugitive. That is, unless you knew the show's creator, Roy Huggins. In an interview with the LA Times, Huggins pooh-poohed assertions that Sheppard was his muse. In fact, he denied knowing anything about the doctor while fleshing out The Fugitive, instead framing it as a modern-day Western. Making the main character a doctor, he claimed, made him believable.

Perhaps the show's Sheppard connection is purely incidental. If so, it's among history's eerier accidents. Consider, for example, that The Fugitive's protagonist Richard Kimble shares his first name with one of Sheppard's brothers, who also happened to be a doctor. (That's a bit like naming a movie character John Wilkes and randomly making him a homicidal actor.) And to get some of the more specific details, Huggins would have needed to know someone close to Sheppard, right?

That brings us to Sheppard's mistress, Susan Hayes. In The Wrong Man, author James Neff noted that in 1956, Hayes married Ken Wilhoit, who edited music for The Fugitive. Neff claimed this led people to falsely link the show to Sheppard. But is that plausible? Wilhoit worked on 119 of The Fugitive's 120 episodes while wedded to a woman who canoodled a Kimble-esque murder suspect and testified at his trial. Did he simply hide that from his bosses and coworkers? Admittedly, such insinuations prove nothing. But in the court of public opinion, appearances mean everything.