Recent Discoveries That Proved We Got History All Wrong

The trouble with history is that pretty much everything that happened before the 20th century had to be written down, and people are terrible eyewitnesses. We may never really know what happened even during very well-documented historical events like The Alamo or the Battle of Bosworth because historians often embellished details, recorded fiction as fact, or wrote down only what the ruling class wanted people to know. And before humans developed a written language, well, all those moments are lost in time, like tears in rain. (Thanks, Roy Batty.) But every now and then some new, tantalizing details emerge from the archaeological record, or from a previously neglected document, or even from someone's DNA. And sometimes those details are so surprising that they completely change our understanding of history.

Some modern people carry the DNA of other human species

We've known for a while now that genetically modern people sometimes mixed with Neanderthals, and since genetically modern people were probably also responsible for the eventual genocide of the Neanderthal species, such liaisons were probably the caveman equivalent of Montagues and Capulets, only hairier.

New evidence has discovered that such intermixing of different human species was not just confined to Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. According to the BBC, besides us, there were once at least four other species of hominids living on planet Earth at the same time, including the Neanderthals, the Denisovans (who lived in southern Siberia), a small Indonesian hominid appropriately nicknamed "the hobbit," and Homo naledi, which was discovered in a South African cave system in 2015.

Neanderthal DNA is found in humans who originated outside Africa, and can make up 1 to 2 percent of those individuals' genomes. Denisovan DNA makes an appearance in the genomes of people living in East Asia and Oceania. And in 2016, statistical geneticist Ryan Bohlender revealed that Pacific Islanders may carry the DNA of another unknown extinct hominid. So it's starting to become clear that intermingling of species was far from just the occasional clandestine affair between star-crossed lovers — it happened so frequently that it's possible that you personally owe your jawline, sense of smell, or preference for hanging out in caves to an ancient, almost-human ancestor.

The first Americans didn't cross the Bering land bridge

This is sort of like saying that Columbus didn't discover America or that dogs and cats like each other. Except oops, Columbus totally didn't discover America, and some dogs and cats do like each other, though mostly just in Internet memes. The idea that the first Americans crossed the Bering land bridge is beloved in grade school history classes, but there's new evidence that it's probably not true.

A study published in 2016 pointed out that during the time of the first crossing, Beringia didn't have the resources needed to support a large population of migrants. Animals and plants didn't start to make homes in Beringia until around 12,600 years ago, and the first crossing was more than 1,000 years before that. Instead, it is likelier that the first migrants crossed into the Americas by traveling along the now-submerged Pacific coastline.

If you're still totally bummed that Beringia wasn't on the itinerary of the first Americans, don't worry — it's still pretty likely that other groups used that route, just much later on.

Viking warriors could be women

If you're a fan of Vikings on History Channel, you'll probably find this information to be about as eye-rolling as it gets because duh, everyone knows shield maidens were a thing, and Lagertha could totally kick your butt, by the way. If you're not a Vikings fan, here's proof that Lagertha and her shield maiden cohorts aren't just based on some stuff in the Viking sagas that some ancient historian or another randomly made up.

In the 1880s, the skeleton of a Viking warrior was unearthed in Sweden, and everyone just assumed the skeleton belonged to a man, mostly because Xena Warrior Princess wouldn't reach the airwaves for more than a century. The warrior, who was buried with weapons, shields, and two horses, helped historians imagine what the quintessential Viking warrior might be like, except for the part where he was a she.

The New York Post reported that the skeleton remained incorrectly gendered until recently, when an osteologist noticed the fine cheekbones and "feminine hip bones" and decided to do a DNA analysis. What they discovered will not surprise Vikings fans, but as far as most everyone else's understanding of Viking culture is concerned, it's right up there with Vikings not wearing horned helmets on the grand scale of shocking Viking-related information. Let's review: viking warriors could be female, and they could also be military leaders. So in a way, the Viking hordes were more progressive than we are.

Dinosaurs weren't cold blooded ... or warm blooded, either

The word "dinosaur" means "terrible lizard," and it's not because dinosaurs liked to hang around in bars late at night and use cheesy pickup lines on girl dinosaurs. It's because people thought they were big lizards.

When the first dinosaur fossils were discovered in the 1600s, no one really knew what to think. According to the BBC, 17th-century museum keeper Robert Plot identified one fossil as the thigh bone of a huge human, proof that giants once walked the Earth. One hundred years later, another guy came along and gave Plot's fossil the unfortunate Latin name Scrotum humanum, which you'd understand if you looked at Plot's original illustration of his find. Incidentally, in the 1990s two British scientists had to beg the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature to permanently erase the name from the list of official dinosaurs, which has absolutely nothing to do with this story but was too good to leave out.

By the 1850s, scientists knew that dinosaurs weren't gigantic humans or terrifyingly large scrotums, but they couldn't imagine them any other way than stocky and low to the ground like iguanas. And with that assumption came another one: dinosaurs were lizards, so they were cold-blooded. In 2014 that someone finally decided to research the question — a team of biologists used a formula of growth rate, body temperature, and size to conclude that dinosaurs must have been somewhere in between. They couldn't exactly regulate their body temperature, but they weren't lumbering and sluggish, either.

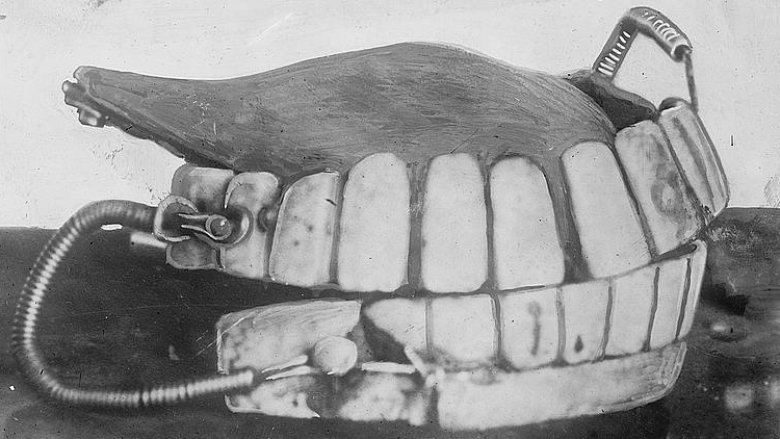

George Washington didn't have wooden teeth

The composition of George Washington's dentures isn't exactly the sort of historical detail that brings down regimes or rewrites entire textbooks, but like the cherry tree he never chopped down and the silver dollar he never threw across the Potomac, it's a myth so beloved that it seems immune to gravitational logic.

George Washington did not have wooden teeth, though it is possible that as he aged his dentures became so disgusting that they looked like they were made out of wood. Just imagine how gross they would actually have to be to get to that point. Anyway, because for some reason they were troubled by the persistent myth that George Washington's teeth were wooden, and because for some reason his teeth ended up in a museum, NBC News says researchers decided to settle the argument by subjecting said teeth to a series of laser scans. At long last, the answer: Washington's teeth were made out of ivory, gold, lead (yikes), and actual teeth, some of which were human and some of which were animal. Now one wonders why they weren't all ivory, all gold, or all donkey, but that would just be too insanely rational, and if we believed that Washington's teeth were rational, well, we might not believe that thing about the cherry tree and then where would American history be?

Incan children were drunk when sacrificed

The Inca civilization was the largest-ever empire in the Americas, but it was terrified of its own vulnerability. According to The Guardian, the Incas lived in a volatile environment where natural disasters were regular events, and they believed they had to take drastic measures to protect their civilization. While we modern people usually just blame whoever is president and then sit around complaining for four years, the Inca decided they'd better kill a bunch of little kids to appease the gods.

Contrary to popular assumption, Inca child sacrifices were not ripped from the arms of their parents — they were usually the children of wealthy families who offered them up willingly because there was a certain prestige to it. In death your kid became a god, and you got to be a mom god, and that was pretty cool if you overlooked the whole death-of-your-beloved-child part of the equation.

Up until recently it was pretty hard to fathom how children could go happily to their deaths, even if they were brainwashed into thinking they could have bottomless french fries and unlimited video games in the afterlife. In 2013, Gizmodo reported that Inca sacrifices were given coca leaf and corn beer in increasing quantities for up to a year before the sacrifice, and then they were loaded up with more beer until they passed out. That made it easy to put them into their ritual tombs, where they quietly and complacently froze to death.

Cats domesticated us

Most domesticated animals are descended from social species, which in part helps to explain how we were able to domesticate them. Animals that live in social groups are used to taking orders from an alpha, and all we really did was step in to become the new alpha.

Then there's the cat. All house cats are descended from the African wildcat, and the funny thing about African wildcats is that they aren't social animals — females are solitary unless they're raising kittens or are in search of a mate. So how did we manage to become the cat's alpha? As any cat can tell you, we didn't.

According to research led by Yaowu Hu of the Chinese Academy of Science, early evidence of cat domestication can be found in 5,300-year-old Chinese refuse pits, where researchers discovered the bones of rodent-eating cats. But at least one cat found there wasn't eating mice, it was living off the 3300 B.C. equivalent of Fancy Feast. So although it's true that humans benefited from cats taking over rodent control, it's also true that at least one ancient cat managed to sucker people into taking care of it even though it had the hunting prowess of a middle-aged tax attorney living in Brooklyn. And because African wildcats don't take orders from any alpha, the only logical explanation is that the cat was the alpha. And so it was, and so it ever shall be.

King Tut wasn't murdered

Egyptian kings, ancient curses, buried treasure, mummified erections — the story of King Tutankhamun has everything ... except murder. The boy king did not meet his end at the hands of a political rival or a jealous lover, instead dying in a pretty damned boring and ordinary way.

The thing about Tut is that he's not famous for building the pyramids or bringing monotheism to Egypt or anything like that, he's famous because he was buried with a buttload of treasure and no grave robbers were ever clever enough to figure out where it was, until 1922 when some white guy broke in and then subsequently died from a mummy-cursed mosquito bite. Before that there wasn't a lot written about Tut, and his cause of death was pure speculation. Because he died so young, some people thought he must have been murdered — theories ranged from a blow to the back of the head courtesy of a political rival to poison. Then, according to The Guardian, researchers had to rain on everyone's murder mystery parade with DNA tests and CT scans, which revealed that the king suffered from severe malaria and an infected, broken leg. And the poor kid wasn't just sick, he also had a cleft palate and a club foot, which were inherited conditions — the genetic testing also revealed that his parents were brother and sister. So the real story here is not how King Tut died, but that he was a Targaryen, or possibly one of Cersei's kids.

Ancient beer was probably disgusting

What would you do if you suddenly found yourself in possession of a 5,500-year-old Mesopotamian beer recipe? You'd brew some beer. And that's exactly what Gizmodo says a team of University of Chicago archaeologists did with the help of some pro beer-makers from the Great Lakes Brewing Company in Ohio. It would have been wrong not to.

The team was going for authenticity, so they used a ceramic vessel just like the ones archaeologists dug up in Iraq, they used yeast from a "beer bread" made by a baker in Cleveland, they malted the barley on a rooftop, and they warmed the mixture up over a pyre of burning poop. When they were done, they had a concoction one team member tactfully said was "too sour for the modern tongue," which was basically like admitting that the stuff tasted like Pabst Blue Ribbon with half a Mickey's and a quart of Bragg's apple cider vinegar. But hey, 5,500-year-old beer, right? Cool.

Human ancestors could make abstract art

Modern humans have long been thought to be the only creatures with a concept of abstract art. Surely no other creature could possibly be advanced enough to throw a can of paint at a wall and then pretend it was so much more than a temper tantrum. Evidently all this time we were wrong — according to Science Magazine, our ancient ancestor Homo erectus also appears to have had some ideas about abstract art.

In 2007, a graduate student studying ancient mollusk shells found a zig-zag design carved into a 500,000-year-old fossil. Tests confirmed that the etchings were thousands of years old — they were made before the shell was buried in sediment, and microscopic analysis confirmed they were etched by one person during a single session. The findings do have some critics, however. The shells were discovered alongside Homo erectus fossils, but because the objects were deposited at the site during a flood it's impossible to definitively say that Homo erectus had anything to do with the carvings. Still, the age of the shell suggests the engraving predates the earliest known example of abstract art by at least a couple hundred thousand years. Even though it was really more like a doodle than like Jackson Pollock's Number 25, it does show that human ancestors had some idea of design, or at the very least were capable of fidgeting when bored.

The Clovis people weren't killed by an asteroid

Asteroids! They keep NASA scientists up at night and inspire really terrible Ben Affleck movies. We adore them because, like Yellowstone calderas and nuclear bombs, they have the potential to instantly and completely end civilization as we know it, and that makes Hollywood happy.

An asteroid wiped out the dinosaurs, and for a while some scientists believed that an asteroid wiped out the Clovis people, too. In case you aren't really sure what the deal is with the Clovis people, National Geographic says they were some of the first migrants to reach the Americas, somewhere around 13,000 years ago. The culture was short-lived — a couple of hundred years after they arrived, their characteristic spear-points disappeared from the fossil record, which seemed to indicate that they themselves disappeared from planet Earth.

So what happened to the Clovis people? A 2006 theory suggested that a comet struck the Earth, which caused wildfires, mass extinction, and probably other post-apocalyptic horrors like cooperation between Republicans and Democrats. But in 2011 a pair of archaeologists called foul on the theory, citing a lack of extraterrestrial particles at many Clovis sites and no indication whatsoever that the population of North America declined around that time, or that Republicans and Democrats were getting along. The new theory: The Clovis people stopped making that particular sort of spear point and came up with a new design. Bet you'll never see that in a Ben Affleck movie.

Richard III wasn't a hunchback

Shakespeare called him a "poisonous bunch-backed toad," which would have been pretty mean if it was true and he'd lived to hear the insult. As it turns out, Richard III was not hunchbacked and couldn't have been used as an ingredient in poison darts. Today we know that being hunchbacked has nothing to do with personality, but remember this was a time when people dumped their chamber pots into the river, so they weren't exactly predisposed to political correctness. Still, the "bunch-backed" description persisted from Tudor times right up until Richard's skeleton was found buried under a parking lot in 2012.

At first, the skeleton's profoundly curved spine made everyone think that Shakespeare had been right, but according to CNN, researchers later showed that the king's scoliosis wouldn't have troubled him much and certainly wouldn't have been obvious to most people. There's also no evidence that he limped, had a permanently tilted head, or a face like a toad — in fact his contemporaries described him as "the most handsome man in the room after his brother." So what's with the whole hunchback thing? Richard's Tudor successor didn't really have much claim to the throne, and to protect it he had a pretty strong interest in making himself look like the better man for the job. Clearly, a hunchback with a "poisonous" personality would have been a lot worse than the guy who founded the Tudor dynasty and fathered Henry VIII. He did, in fact, have a poisonous personality, but that's another story.