The Legacy Of Johannes Gutenberg Explained

The details of the life of the German inventor Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg — who, in the 15th century, invented the movable-type printing press, which would change the course of history forever — are intolerably few and far between. Like William Shakespeare, the exact date of his birth is unknown, and many aspects of his biography are open to speculation.

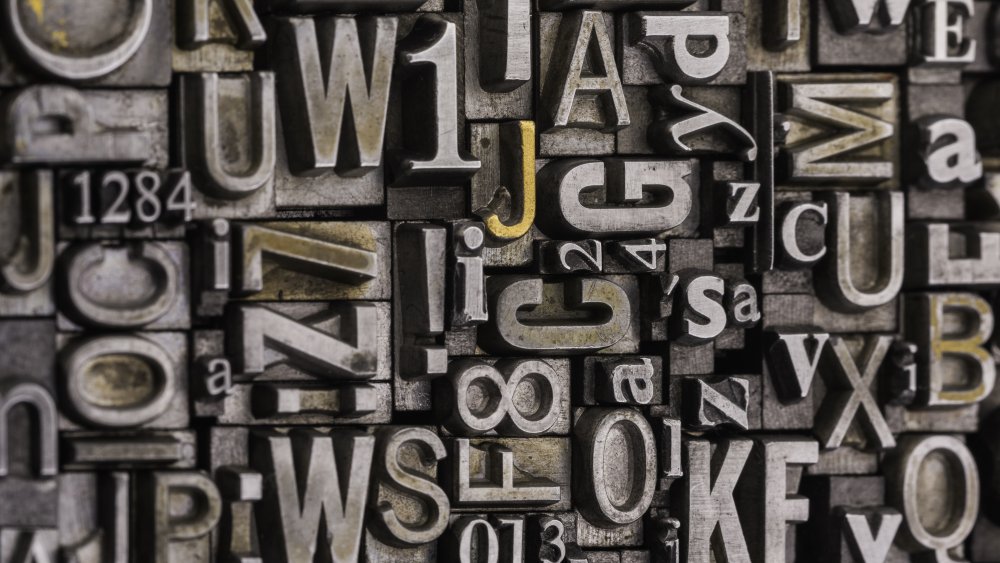

However, the importance of his contribution to Western civilization has never been in doubt. Moveable type — a process by which cast metal letters are arranged as separate pieces within a frame, which (unlike a full woodcut) meant that arrangements could be made quickly and mistakes in printing easily rectified — rapidly increased the speed at which information could be transmitted, with great repercussions for everything from news to politics, from art to science, and everything in between.

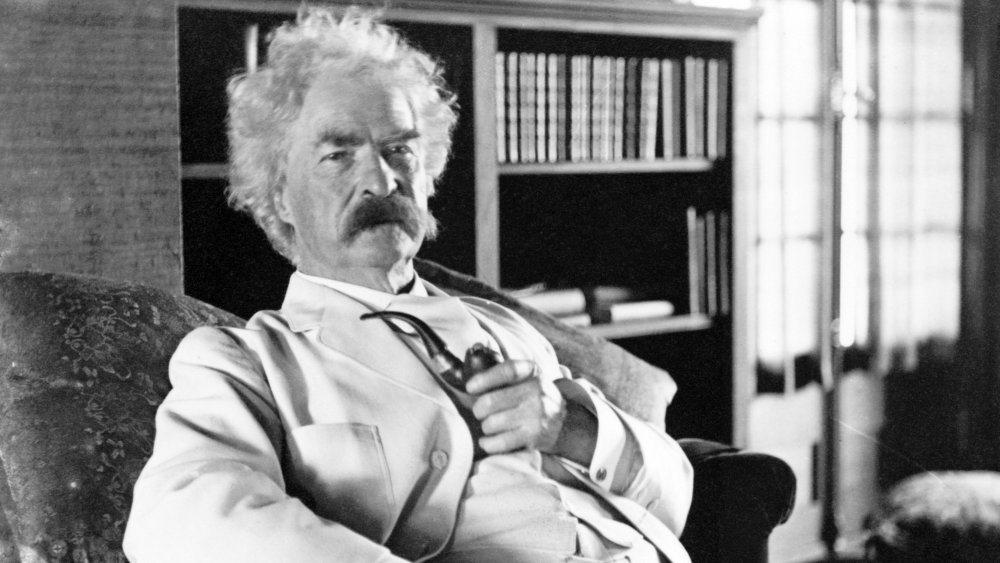

Like the internet at the turn of the millennium, the transformative power of Gutenberg's invention was so utterly all-encompassing that to characterize it idealistically as "progress" or "a benefit to mankind" is to take a naive view of its influence. In a typically thoughtful letter sent to the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz in 1900, Mark Twain claimed that, "All the world acknowledges that the invention of Gutenberg is the greatest event that secular history has recorded," but also that "What the world is to-day, good and bad, it owes to Gutenberg." Well into the age of electronic information, we may find that this is still the case in the 21st century — for both the good and the bad.

The beauty of the Gutenberg Bible

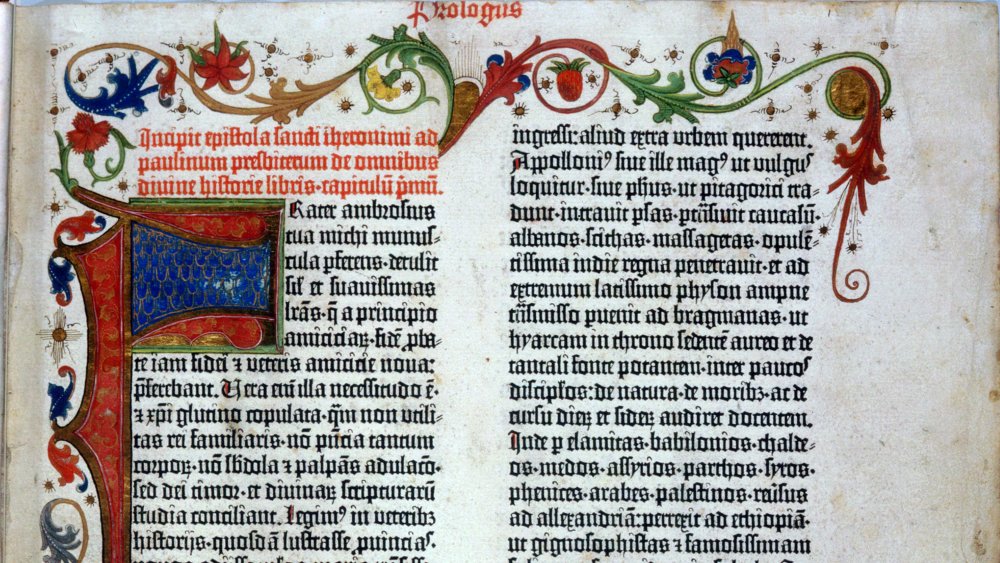

Until Johannes Gutenberg's invention, the vast majority of books were inked by hand on vellum — animal skin — especially in the case of religious texts. This was a long and costly process, which meant that the limited number of books produced were kept in the hands of a small circle of elites: aristocrats and members of the clergy. In addition to their lettering, such texts were "illuminated" with a great range of beautiful hand-painted imagery adorning the margins around the text body, which reinforced the sense of each hand-crafted text being a holy object in its own right.

The first documents that Gutenberg printed with moveable type were short, such as legal documents and notices, but upon realizing the possibilities of moveable type, it didn't take long for the inventor to set his sights on the ultimate goal. According to the British Library, his project was to produce printed versions of the Bible with his new machine, with the coloring of the "illuminations" the only aspect of the printed work that was hand-finished. The first run, which has been estimated to have been just under 200 copies, sold out before production had finished.

The choice of the Bible as the first full Gutenberg text may seem obvious, but its significance for the new invention was huge in that it demonstrated that Gutenberg's technique produced objects that were legitimate carriers of the authoritative status of holy writings and that such objects could be just as beautiful as those created entirely by hand.

Printing was vital to Martin Luther's Protestant Reformation

"Going viral" is a term we usually associate with social media and the internet — but The Economist has recently found it a suitable phrase to describe the explosive arrival of Protestantism over 500 years ago. Why?

Many of us are familiar with the story of Martin Luther and how, on October 31, 1517, he nailed to the door of the church in the German town of Wittenberg his challenge to Catholicism, "95 Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences." Indulgences were a common occurrence in the Catholic Church: They allowed rich followers to atone for their immoral behavior and those of family members already passed over, whom they feared might be stuck in Purgatory. Luther felt that such a system suggested the rich could buy their way into Heaven, which, honestly, doesn't sound very, well, Christian, does it?

His antagonism against the practice was central to the formation of Protestantism, but the legendary event in Wittenberg was likely not as instrumental in spreading his doctrine as Luther's use of Gutenberg's method of printing, which allowed for what the Library of Congress describes as "history's first media event." The dissemination of his ideas was rapid, with tons of his theses and other Protestant pamphlets spread around Europe within just a few years, and aided Luther's sharing of his German translation of the Bible — at the time considered blasphemous — changing the course of Western Christianity for good.

The newspaper and mass media

Today, the newspaper as a physical printed object is in decline, with consumers continuing their migration to other media such as televised news and, most of all, the internet. Traditional news publishers are now grappling with how to monetize their output, with many attempting to secure online subscriptions from previously loyal readers of their product. But while the documents themselves are on the wane, the freedom of the press which is now a fundamental aspect of Western society owes itself to the development of printed newspapers in the decades and centuries following Johannes Gutenberg's development of moveable type, according to Britannica.

With newspapers appearing all over Europe around the start of the 17th century, the spread of news and information about events in foreign lands reached more people than ever before. However, at the time, many of these publications were subject to state control, with newspapers barred from reporting on local events or even commenting upon political developments in their native lands. It took treatises by writers such as John Milton in England to argue for the independence of publishers as a whole. Such assumptions around the role of newspapers and the importance of free speech in allowing journalists to critique those in power and the systems that enable them are constants that, hopefully, we will continue to abide by as the landscape of journalism continues to change in our own time.

Printing brought classical texts to the Italian Renaissance

Many factors affected the great flowering of ideas and progress that occurred during what is commonly termed "The Renaissance." According to History, the Italian Renaissance had been underway for a century before Gutenberg's printing press was invented, with governors of the country making concerted efforts to recreate their society along the lines described in the texts of ancient Greek and Italian philosophers and thinkers. But the sudden influx of printed books and the capabilities of presses around Europe meant that the availability of works by classical philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle skyrocketed, which allowed for their ideas to take root and guide the direction of society for centuries to follow.

The influence of Petrarch, whose 13th-century works were given new life during the Renaissance thanks to the printing press, was especially strong, with the Italian poet bestowed the title of both the "Father of the Renaissance" and the "Father of Humanism." His secular ideas led to the common formulation of man as being at the center of his own universe, an idea which would dominate culture for much of the second millennium A.D.

The strengthening of vernacular languages

What was the common language in which books were written before Johannes Gutenberg's printing press and the advent of moveable type? The answer, for most of Europe at the time, is Latin. The purpose of this, particularly with Christian texts, was ostensibly to maintain the sanctity of the Holy Word — that the ancient language was closer to that of God than the contemporary everyday languages of Europe at the time. The other purpose of using Latin as the dominant written word was more nefarious, however — in that it kept access to the texts themselves out of the hands of normal people.

According to ThoughtCo, the printing press led to an explosion of texts being written in the native languages and dialects of individual countries, which aided the increase of literacy but also led to a level of cultural self-awareness that hadn't previously been experienced by the populations of European countries. These practices then went on to inform policy and the direction of the Church — in England, the commission of the King James Bible at the turn of the 17th century was a watershed moment in the way that religious texts were consumed and the relationship between scripture and native languages was thought about.

The emergence of the literate middle class

The printing revolution started by Johannes Gutenberg and the invention of moveable type was essentially the dawn of the age of mass communication, which effectively altered the shape of society for good. Not only did printing allow for more people to read the established texts of Western literature, but the price of printing allowed for a greater range of perspectives to emerge and for the hierarchies that had dominated previously to be challenged.

As noted by Lumen Learning, the sharp rise in literacy and access to education meant that the divide between the top and bottom of society began to narrow — and a large, literate, and educated middle class began to emerge throughout Europe. Such growth was self-perpetuating, with the middle classes accounting for the vast market that drove the demand for printed materials and the dissemination of texts into the hands of an increasingly literate European society.

The possibility of the novel

Today, when we think about getting lost in a good book, we tend to think of the novel, which has been the predominant form of literature in terms of sales, popularity, and critical interest in recent centuries. But this was not always the case.

In fact, the novel is a rather modern invention, the existence of which is entirely dependent on Johannes Gutenberg's pioneering use of moveable type. According to the University of North Georgia, in the distant past, narratives were primarily shared through the form of the epic poem using the oral tradition: Often, these poems weren't even written down but were memorized, calling for the use of rhythm, rhyme, and poetic motif to help the speaker to recall the flow of the story. Similarly, news and the few books that communities could afford were often read aloud to groups of people, a consequence of the price of printed materials and limited literacy.

With the arrival of the printing press, not only could more people afford books, but the forms in which literature was written and shared were able to change. Cheap printing meant that stories not only required no memorization, but they could go on at length for volumes and volumes, ultimately leading to the epic novels that are familiar to us when we think of Dickens, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky. These books were targeted at independent readers, who were no longer required to read in a group and could afford to buy books, pamphlets, and newspapers for themselves.

The sharing of scientific knowledge

As a logical system of describing and interacting with the world, science is today considered an authoritative and objective force for good. But the scientific method upon which it is based could never have risen to prominence if it weren't for Johannes Gutenberg's printing press.

Formulated in the early 17th century by Francis Bacon, who has been described as the "Father of Empiricism," the scientific method relies on the abandonment of preconceptions and the empirical observation of facts within a defined and stable system of experimentation. Printing made two great contributions to what would later be known as the Scientific Revolution, according to History. First, cheap printing transformed scientific experimentation from a solitary activity to a shared network of activity, results, and ideas, in that information and data were able to travel between scientists and interested parties. More importantly, however, the sharing of data became infinitely more reliable in the absence of human error in the copying process, meaning scientists were more able to trust the data they were working with. The advent of the printing press pushed forward the vanguard of scientific endeavor.

Counterculture and outsider voices

Starting with Martin Luther, printing has worked as a vector for the sharing of new ideas. But its importance has waned little in the intervening years, and even now, in the age of the internet, it's arguable that printing still plays a large part in amplifying fringe voices, as noted by History.

Consider any countercultural movement of the past century — from the Beat Generation in the 1950s to the hippie movement of the 1960s, to punk and skate culture. Each has been associated with an array of cheaply printed pamphlets, 'zines, manifestos, and artworks that have come to define the aesthetics and tone of the movement. In some cases, such documents have worked to announce the movement and its members to the world. In other cases, printing has been used to inform others about issues that need to be dealt with — such as in the anti-war movement in the U.S. in the '60s.

In the present day, with opposition to the digitization of personal data and the privacy risks this poses for political activists, commentators have highlighted that, once again, print is becoming the medium in which ideas are shared in a way that is tangible, durable, and, above all, cheap.

Project Gutenberg

The digital archive that takes its name from Johannes Gutenberg himself is perhaps the most obvious aspect of his legacy, but it is also an important one for what it represents about the democratization of knowledge and the attitude that modern societies have toward knowledge-sharing as a direct consequence of Gutenberg's invention.

Project Gutenberg began in 1971 as a volunteer-based project to digitize and archive print works, creating and distributing eBooks for free. Starting with books on which copyright had lapsed and which were thus in the public domain, the archive now includes many titles written later, all available to download on almost any device and compatible with most eReaders. The archive today holds now more than 60,000 titles, from adventure books to philosophical tracts, in a range of languages.

It's easy to see why such a project adopted the Gutenberg name, in that, like the printing press, the project aims to spread knowledge evenly to as many people as possible.

Censorship and propaganda

An invention as universally transformative as the printing press is bound to have unforeseen consequences. And in its most radical aspects — such as in the voicing of challenging ideas — the advent of moveable type has meant that those in power have felt obliged to take steps to curb its effects.

Censorship itself is nothing new. According to Beacon for Freedom of Expression, the role of censor first existed in ancient Rome, when it was believed that good governance involved guiding the way people thought and shaping the knowledge of the populace in a way that would best serve society as a whole. But after Gutenberg, the new freedom of information brought with it new opportunities for the curtailment and suppression of newly empowered voices. In 1559, Pope Paul IV ordered the first Index of Prohibited Books, which banned works by figures such as Galileo and Joan of Arc, seeking to limit the dissemination of literature that would challenge the primacy of the Catholic Church. The index was reissued by a subsequent 20 popes. On a national level, censorship has long been used to ban books thought to be morally subversive. The act of book-burning has also recurred throughout recent centuries.

Censorship also goes hand in hand with propaganda. Especially during times of war, officials have been keen to shape the narrative of how war efforts are developing, to deflect blame from themselves, or to reinforce official dogma. An extreme form of this continues today, in the age of rampant disinformation – or "fake news."

Did printing increase the scale of war?

Mark Twain's incredibly balanced view of Gutenberg's legacy is worth returning to. Two versions of Twain's letter concerning the printing press exist, and he begins both by describing the request to participate in the celebration of Gutenberg and his achievements as a "great pleasure" and an "honor." Twain claims: "Gutenberg's invention has supplied both earth and hell with new occurrences, new wonders and new phases. It found truth astir on earth and gave it wings; but untruth also was abroad, and it was supplied with a double pair of wings."

The double effect of the printing press has been seen in censorship and propaganda, but an even darker aspect of the invention occurs to Twain: its role in the scaling up of war itself. "War," says Twain, "which was conducted on a comparatively small scale, became almost universal through this agency. Gutenberg's invention, while having given to some national freedom, brought slavery to others. It became the founder and protector of human liberty, and yet it made despotism possible where formerly it was impossible."

The parallels we can draw today to the internet and the dawning of the information age — as well as with globalization through technology — are striking. Humanity's scale is huge, but so, too, are our problems. What remains to be seen is whether our interconnectedness can overcome "untruth" to bestow us with the "agency" we need to effect global change.