The Messed Up Truth Of Canada's Starlight Tours

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis in Canada have long known that the police cannot be trusted and that Canada has a pretty problematic history overall. But it took until the early 2000s for one of the more horrific police practices targeting Indigenous communities, known as "starlight tours", to be investigated. However, police often didn't leave a paper trail, which left little evidence for convictions even today.

But unfortunately, even when there is evidence that a starlight tour occurred, the most that will often happen is that the police officer will be slapped with a minor charge, serve a handful of months, and perhaps get fired. Meanwhile, those who survive starlight tours are haunted by the memory of their experience and suffer life-long physical and mental consequences.

Although police abuses in Canada are sometimes referred to as starlight tours when they involve being driven in a police cruiser, the starlight tours of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan present a horror all their own. Tragically, there's no way of knowing exactly how many people have been victims of starlight tours in Saskatoon or elsewhere. Those who survive often don't speak out because, according to a CBC report, "it's police investigating police." This is the messed up truth of Canada's starlight tours.

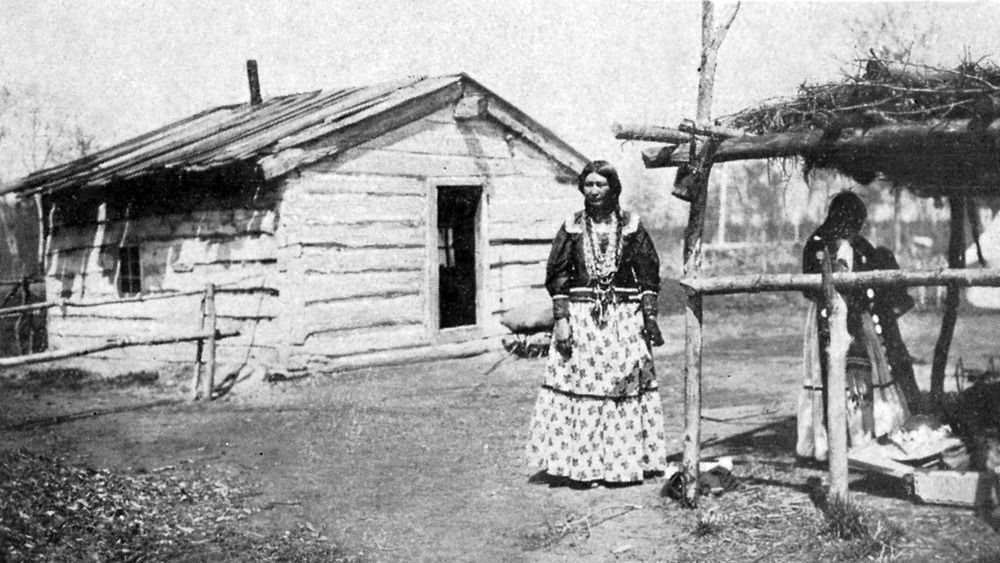

A brief history of First Nations people in Canada

Although the Indigenous population of Canada numbered in the hundreds of thousands before European colonization, those numbers had fallen to about 125,000 recorded individuals by 1867. Canada's Indigenous people have fought against diseases like smallpox, scourges as rampant as warfare, and assimilation measures like those also forced upon Indigenous people in the United States.

According to Origins, Canada identifies three broad groups of Indigenous peoples as First Nations, Inuit, and Métis, who are legally differentiated depending on their ancestry. And while Canada chose assimilation and segregation compared to the United State's policy of extermination, the National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health reports that Indigenous people continue to be oppressed by systemic racism. Under the 1876 Indian Act, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia, many First Nations people were confined to reservations like their Indigenous neighbors in America. The Canadian government implemented a "myriad of regulations, controls, and limits on Indigenous peoples designed to crush their way of life", Origins reports.

In 1886, the Indian Act was amended to make "Indian Residential Schools” mandatory for Indigenous children. Thousands of children were isolated from their communities and traditions in unhealthy and dangerous schools. According to the Independent, over 3,000 children are recorded to have died as a result of the horrifying abuse they experienced at these schools, and at least a dozen died in an attempted escape. The last federally run school wasn't closed until 1996.

What are starlight tours?

In the 2000s, another horrifying practice was brought to the non-Indigenous Canadian public's awareness. Known as "starlight tours," "starlight cruises," or "midnight rides," this appalling practice involve a police officer driving an Indigenous person to city outskirts and leaving them there to, as the Human Rights Watch reports, "walk home in the dead of winter, risking death by hypothermia."

Although the most well-known incidents occurred in 1990, starlight tours have been recorded as early as 1976. Maclean's reports that many incidents happened in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. According to The Conversation, the practice is especially lethal "when the temperature is -28°C [-18.5°F] and if the long walk back to town is undertaken without proper clothing and shoes."

Racialization, Crime, and Criminal Justice in Canada reports that, although Indigenous organizations and activists repeatedly demanded a public inquiry, the Saskatoon Police Service insisted that starlight tours were "a myth." Meanwhile, per CBC News, some believe that starlight tours weren't inherently sinister and instead "grew out of police frustration at dealing with repeat offenders." Since the police were said to target "drunk or rowdy" individuals, the practice could have been intended to avoid booking people and instead give them a chance to walk off their intoxication. However, other than the fact that this is a terrible way to help someone sober up, this practice is nothing more than a blatant abuse of power by the police force.

The first documented case of a starlight tour

The first recorded case of a starlight tour occurred on May 22nd, 1976, according to Starlight Tour: The Last, Lonely Night of Neil Stonechild. During the night, three First Nations people, an eight-months pregnant woman and two men, were taken from a party by Constable Ken King, driven to the outskirts of the city, dropped off by the isolated Queen Elizabeth power station near the South Saskatchewan River, and forced to walk back in the deadly freezing temperatures. This area was notorious as a dropoff point for Indigenous people, as houses are far enough away that anyone left there by police wouldn't be heard. All three Indigenous people survived this nightmarish experience.

According to Starlight Tour, King reportedly drove them outside the city limits as a punishment for "having liquor in a place other than a dwelling" but neglected to charge them as such. Constable King ended charged with discreditable conduct and neglect of duty and, although he denied the charge, was found guilty and fined $200 on October 15th. However, this fine only amounted to a week's pay.

Who was Neil Stonechild?

Neil Stonechild was a Saulteaux-Cree First Nation teenager who was found frozen in a field on the outskirts of Saskatoon in 1990, The Conversation reports. Police claimed that Neil was responsible for his own death, though he had clearly been injured.

According to the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Matters Relating to the Death of Neil Stonechild, while the pathologist who examined Stonechild's remains determined that his cause of death was hypothermia, the Saskatoon Police Service decided that there was "no evidence of foul play."

The night Stonechild was abducted, five days before his body was found, the CBC reports that Stonechild was seen by his friend Jason Roy handcuffed in the back of a police car "with his face cut open, bleeding." According to the Canadian Journal of Women and the Law, upon viewing Stonechild's body before burial, his family noted that it looked like his nose had been broken and the marks on his wrists "looked like handcuff marks."

Although these injuries corroborated Roy's account and he twice submitted reports to the police, no one faced any real consequences. Instead, police maintained that Stonechild died of exposure while on the way to prison to turn himself in. But Roy maintained that there's no reason the police would have let Stonechild go under normal circumstances.

Despite struggling with alcoholism, Roy remembers how "Neil loved life. He was a giving person who enjoyed just being a young kid."

Darrell Night's abduction and starlight tour

On January 28th, 2000, Darrell Night became another victim of the starlight tours, although Maclean's reports that he was thankfully able to survive the three-mile walk home in -7°F weather. Driven outside the city limits of Saskatoon by Officers Ken Munson and Dan Hatchen, Night walked back with just a T-shirt and a jean jacket.

According to VueWeekly, Night says that he was leaving a party when the two officers grabbed and cuffed him. Dumped out into the freezing weather, he called out to the cops driving away, terrified. Their only response was "That's your f—ing problem." Later, when Munson and Hatchen were asked to explain their actions, they claimed that Night had "wanted to be dropped there to 'walk off his anger'."

Finding his way to a power station, Night caught the attention of a security guard and called a taxi. He made it home, becoming one of the reported survivors of a starlight tour. Although Night filed a report, Niche Canada reports that he didn't expect anyone to believe him. But, within days, the frozen bodies of two more First Nations people were discovered in the same area Night was found. As a result, Night was asked for a full report, setting off a chain of events that included reopening the Stonechild case and revealing to the public the extent of this police practice.

More deaths by the power station

On January 29th, 2000, the day after Darrell Night's abduction, the body of Rodney Naistus was discovered near the Queen Elizabeth power station. Several days later, on February 3rd, Lawrence Wegner's frozen body was also found in the same location. Both of these remains were discovered close to the same spot where Night had also been abandoned by two Saskatoon police officers. The police were finally forced to investigate.

According to the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Matters Relating to the Death of Neil Stonechild, in response to these deaths and Night's allegations, the Attorney-General for Saskatchewan ordered the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to investigate the freezing deaths.

Although Stonechild's death was not included as part of the initial investigation, after the Saskatoon StarPhoenix published an article by Leslie Perraux that linked Night's story with the 1990 death of Neil Stonechild, the RCMP decided to finally investigate Stonechild's death as well, almost a decade after his death.

Starlight tours led to ineffective inquests

Despite the growing attention, neither Naistus's or Wegner's investigations ended up producing any criminal charges. According to Starlight Tour, "no police involvement was proven in Naistus's death." Instead, it was claimed that Naistus simply wandered away from a house party, possibly while intoxicated, and had frozen to death as a result. The inquests put the onus of responsibility on the victims of the starlight tours, all while insisting that there was no evidence supporting the claims that Canadian police were dropping Indigenous people off in remote, frozen spots. This was despite the fact that Chief Russell Sabo eventually admitted that starlight tours had possibly been occurring for decades.

The inquiry into Darrell Night's incident, however, did result in a conviction, and both Munson and Hatchen were sentenced to eight months in prison. The maximum possible sentence was 10 years. Night eventually left Saskatoon and moved to British Columbia, as he found it incredibly difficult to recover from his traumatic experience while staying in the same environment where it occurred.

Tragically, Night continues to have trouble hearing and communicating as a result of the starlight tour. "I have never received an apology from the police for what was done to me," he told Maclean's.

The inquests for Ironchild and Dustyhorn's starlight tours

Unfortunately, the inquiries into the freezing deaths of Naistus and Wegner mirrored the results of earlier inquests into the deaths of Darcy Dean Ironchild and Lloyd Joseph Dustyhorn in 2000. Both Ironchild and Dustyhorn died shortly after being released from police custody, The Globe and Mail reports.

According to Starlight Tour, Dustyhorn was released from police custody on January 19th, 2000, "despite obvious signs he was hallucinating." He was found dead outside his apartment building only three hours later. Ironchild had also been released from police custody on February 18th, 2000, and was later found dead in his house. Although Ironchild's brother argued that if police had taken Ironchild to a hospital rather than sending him home then he might still be alive, the police were found not to be responsible for Ironchild's death. The same was determined during Dustyhorn's inquest.

Although neither Ironchild's nor Dustyhorn's death technically counts as starlight tours, their deaths and the subsequent inquests were demonstrative of the Saskatoon Police Service's dismissive attitude towards the deaths of Indigenous people.

The inquiry into Stonechild's death

In 2003, 13 years after Stonechild's body was found, an investigation into his death was finally opened. The inquiry lasted a little over a year, and in the end, it was found that Constables Larry Hartwig and Bradley Senger had likely taken Stonechild into custody before his death.

According to the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Matters Relating to the Death of Neil Stonechild, both Hartwig and Senger argued that they were innocent, but there was evidence suggesting that they were deliberating trying to deceive the inquiry. And according to the Saskatoon StarPhoenix, the original investigation into Stonechild's death was described as "superficial at best and was concluded prematurely."

In November 2004, both Hartwig and Senger were fired from duty. Despite appealing their dismissal, they were rejected. However, no criminal charges were filed and, as of 2021, no officer has ever been convicted for a starlight tour. Even when Hatchen and Munson were jailed, they were merely convicted of "unlawful confinement."

An attempt to rewrite the history of starlight tours

In 2016, an 18-year-old university student named Addison Herman was researching police brutality when he realized that the section about "starlight tours" on the Saskatoon Police Service's Wikipedia page had been deleted. Since IP addresses are recorded whenever someone makes a change in Wikipedia, Herman easily discovered that the change had come from the Saskatoon Police Service itself.

According to Maclean's, it's impossible to know who exactly used the police computer to edit the Wikipedia entry, since upwards of 200 people may have been using the same server at the time. Regardless of who editing the encyclopedia entry, Herman notes that "It was a pretty bold move on their part."

The deletion wasn't a one-time thing. Although as of January 2021, the section on starlight tours appears on the Saskatoon Police Service's Wikipedia page, the section was also deleted (and reincluded) at least twice between 2012 and 2013.

How common are starlight tours?

While starlight tours aren't considered an "official police policy", according to Niche Canada, some people report having survived multiple starlight tours in recent years. According to CBC News, "Greg", who didn't want to share his identity because he was afraid of police retaliation, claims that he's survived four starlight tours.

While police can maintain that Greg has a criminal record, many argue that this is still no excuse for leaving him alone 31 miles outside of Saskatoon. Greg remembers that it took him seven hours to get home from one encounter. When asked why he never made a complaint, Greg stated that "it's police investigating police." Alexus Young, a First Nations filmmaker, is another survivor of starlight tours and violence against transgender women, she told the Aboriginal Multi-Media Society. Young said that officers even took her shoes and coat before leaving her outside Saskatoon.

Despite the fact that many stories like this exist, it's difficult to find physical records of these encounters. As a result, it's difficult to know how many people have died as a result of starlight tours.

These incidents aren't limited to Saskatchewan either. According to CTV News, in Montreal, Julian Menezes reached a $25,000 settlement with the city after accusing Officer Stefanie Trudeau of taking him on a "starlight tour". In the incident with Menezes, Trudeau reportedly drove around erratically in order to "scare and intimidate" him, rather than leaving Menezes to die in the cold.

Police brutality against Indigenous people in Canada continues

Police brutality against non-white people is still rampant in Canada. According to CTV News, compared to a white person in Canada, an Indigenous person is "10 times more likely to have been shot and killed by a police officer in Canada". According to the Yellowhead Institute, a Black person is 20 times more likely to be killed by Canadian police than a white person.

This violence can occur even when the police are called for aid. In June 2020, Chantel Moore, a 26-year old First Nation woman, was killed by police in New Brunswick after they were called to her apartment at 2:30 a.m. for a wellness check.

In addition to suffering physical abuse and death at the hands of the police, Indigenous people in Canada who are the victims of crimes are also ignored by the police to a frightening degree. According to the Human Rights Watch, Canadian law enforcement has failed to address problems leading to the disappearances and deaths of Indigenous girls and women in Canada.

Many describe the thousands lost as a genocide. According to The Guardian, Indigenous women are "targeted for violence more than any other group [and are] 12 times more likely to go missing or be killed." Despite the fact that over decades many have repeatedly called for government inquiries into the high rates of missing and murdered women, the government didn't begin investigating this genocide until 2017.