Chilling Details From The Bay Of Pigs Invasion

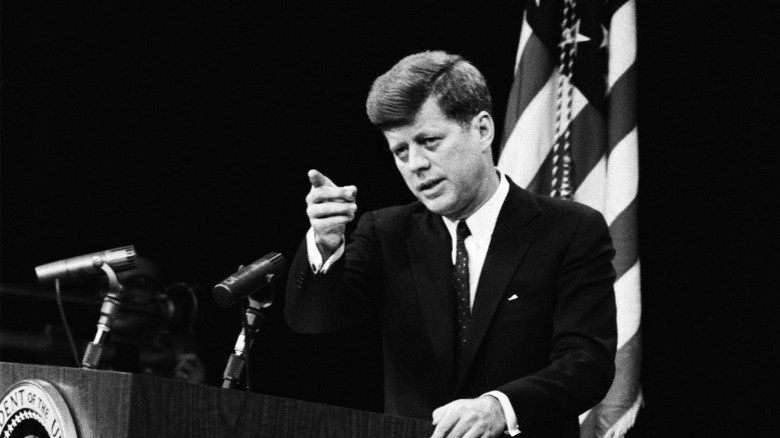

While John F. Kennedy is widely regarded as one of the greatest presidents in U.S. history, his administration was not without its tribulations and scandals. One of the biggest was the failed Bay of Pigs invasion that took place in April 1961. According to the U.S. State Department, the CIA completely planned the invasion, which was aimed at unseating Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro. The attackers set out for Cuba from nearby Guatemala, but the invasion was over almost as soon as it began, and the forces were routed within a few days. The Bay of Pigs is an inlet of the Gulf of Cazones that leads to the Playa Girón beach, located on the southern coast of Cuba.

The failure of the Bay of Pigs led to Castro's Cuba publicly aligning even closer with the Soviet Union, the United States' counterpart in the Cold War. Tensions between the U.S. and Cuba would reach a crescendo 18 months later, when the Cuban missile crisis played out, and the world was brought to the brink of nuclear war. A stain on the legacy of the Kennedy administration, these are the chilling details from the Bay of Pigs invasion.

It started with a Cuban revolution

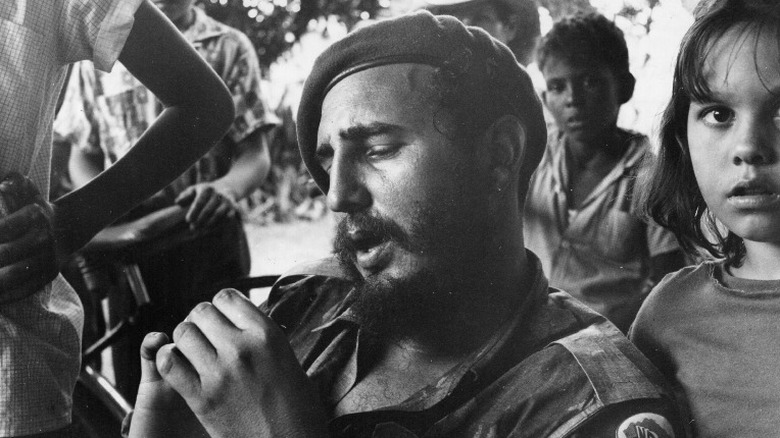

On January 8, 1959, Fidel Castro seized power in Cuba. He entered into Havana, the capital and largest city in Cuba, with his revolutionary organization known as the July 26th Movement (per the College of St. Benedict/St. John's University). That February, he became prime minister, and quickly started to implement agricultural reforms that severely curtailed the size of large landholdings. In April, he started redistributing the land to rural farmers, many of whom lived in deep poverty, and he also initiated a literacy campaign to teach them reading and writing skills. Throughout 1959, the U.S. and Castro still maintained normal relations, and Cuba did not recognize the Soviet Union, at least at first. However, by December, Cuba was admitting official Soviet journalists.

Initially, Washington and the CIA were unsure of how to proceed with Castro. According to Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA," some CIA members like Al Cox, the chief of the paramilitary division, wanted to arm Castro and work with him as an emerging democratic leader. Another CIA officer described Castro as "a new spiritual leader of Latin American democratic and anti-dictator forces." However, feelings in the agency and the Eisenhower administration soon started to change, and Eisenhower would write in his memoirs years later that they were becoming convinced that Castro was bringing Communism to America's doorstep. Given the administration's foreign policy of Massive Retaliation, planning for a military response to Castro seemed inevitable.

The Eisenhower administration started the planning

Growing tensions with Fidel Castro's Cuba quickly brought it into conflict with Washington. According to Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA," it caused the Eisenhower administration, and the CIA, to seriously consider removing Castro from power by late 1959. On December 11, 1959, Richard Bissell, the head of the CIA's clandestine department, communicated with Allen Dulles, the Director of the CIA, about the "elimination of Fidel Castro." Less than a month later, Dulles had Bissell get to work creating a task force charged with organizing Castro's overthrow. In March of 1960, the Eisenhower administration approved the use of covert forces to remove Castro from power.

That August, after plans to assassinate Castro became bogged down, the administration changed course and started to work on plans for an invasion. Eisenhower approved the use of a paramilitary task force made up of hostile Cuban exiles to invade Cuba. Dulles and Bissell had asked for $10.75 million from Eisenhower to start the training of the Cubans, which he agreed to, saying, "so long as the Joint Chiefs, Defense, State, and CIA think we have a good chance of being successful" in "freeing Cubans from this incubus."

Planning for the Bay of Pigs invasion had begun in earnest.

The initial plan was to create a provisional government

The ultimate goal of the Bay of Pigs invasion was to force the removal of Fidel Castro from power in Cuba, and to replace him with a provisional government friendly to the United States. The original invasion plan called for initial airstrikes against Cuban military bases, followed by an invasion on the southern coast by a 1,400-strong paramilitary force of Cuban exiles, trained and supplied by the CIA (per the JFK Library). In "Kennedy's Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam," Lawrence Freedman explains that, while the invasion force was supposed to be fighting against the Cuban Army, a group of exiled Cuban politicians would also land and create a provisional government. The new government would then ask for public U.S. support to help fight against Castro.

The proposed provisional government was to be formed from the Cuban revolutionary organization known as the Frente Revolucionario Democrático (FRD). According to John Prados in "Safe for Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA," Dr. Manuel Francisco Artime, and other disaffected Cubans, created the FRD as an anti-Castro group in July 1960. The CIA directly supported the group throughout 1960, and were subsidizing them with over $130,000 a month.

The CIA trained a secret Cuban army in Guatemala

As soon as Eisenhower approved the use of Cuban exiles to invade Cuba, in August 1960 the CIA set out to start training them (per John Prados in "Safe for Democracy"). They started their search for a training base in nearby Central America, and they settled on Guatemala. The CIA decided on Guatemala for numerous reasons: Not only was it geographically close to Cuba, thus shortening the distance an invasion force would have to travel, but they also had connections with large landholders, like Roberto Alejos, who owned a plantation in the mountains known as Helvetia. Becoming known as "Camp Trax," Helvetia became a CIA training base, after the CIA received the permission of Guatemalan President Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes to train the exiles in his country.

The Cuban force arrived at Camp Trax in August, and had to build their own facilities for housing and shelter. By the end of the month, the invasion force had grown to 160, and in September weapons arrived via CIA air drops. By the late fall, the high-ranking CIA agent Richard Bissell increased the planned number of exiles to as many as 1,500, which started stretching the CIA training staff thin.

Supply drops from the CIA often failed

In addition to the exile force of Cubans training in Guatemala at Camp Trax, there was also a rebel force on mainland Cuba that was in contact with the CIA. The CIA attempted to drop the Cubans supplies starting in October 1960, but the air drops often went awry. Of an estimated 30 supply drops, barely 10% were considered successes (per John Prados in "Safe for Democracy"). In one example of the lack of communication between the CIA and the mainland exiles, the CIA added an extra 960 pounds of beans, rice, and lard to a shipment that was not asked for, and it nearly got the agent caught when it was dropped onto his farm.

Because of the poor external support from the CIA, the Cuban exiles quickly found themselves being hunted down by Fidel Castro's forces (per Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA"). As Castro became thoroughly entrenched as the leader of Cuba, his army and intelligence forces quickly started to track down and capture, or kill, dissident Cubans. The CIA quickly saw their contacts die out, while Castro built his army into a 60,000-strong force armed with tanks and artillery.

The CIA's cover story was a complete failure

The CIA wanted to keep not only their involvement but also the entire Cuban exile force a secret until the day of the invasion. Unfortunately, there were constant leaks that put the plans in jeopardy. According to John Prados in "Safe for Democracy," one of the Cuban exile groups working with the CIA, the Movimiento de Recuperación Revolucionario (MRR), almost blew the operation with an incident near their training center in Homestead, Florida. Some locals threw firecrackers into their secret compound after seeing the exiles training, and the Cubans burst out with their guns blazing. One local was wounded, and the police arrested several of the exiles, who were only freed after federal officials intervened. CIA director Allen Dulles had to induce reporter Stanley Karnow to stop him from publishing a story in a Miami newspaper.

New York Times reporter Tad Szulc found out about the operation in August, and nearly published a national piece about it. In October, a Guatemala newspaper published information about the exile forces training in the country. That report eventually made it into a student newspaper from Stanford University, and that November it appeared in the weekly magazine The Nation. According to the JFK Library, invasion plans were widely known among Cuban exiles living in Miami, and press reports on the unfolding events were widely circulated.

The CIA bombed Cuba

One of the key parts of the CIA plan to invade Cuba was to first destroy the Cuban air force, so it would not be able to fight the exile forces. Fidel Castro's military had at least 12 fighter planes, jets, and bombers, located at bases in Havana and Santiago (per John Prados in "Safe for Democracy"). The CIA wanted to destroy as many of the aircraft as possible to stifle their defenses. The CIA's plan initially called for 16 bombers, but Kennedy cut the number in half just beforehand. The CIA tried to create the impression that the bombers were former members of Castro's military who had defected, in order to further the image of chaos and disorder in Cuba.

The bombings were mostly a success, and on April 15, 1961, the Cuban air force was cut in half. However, the cover story quickly fell apart. Two of the planes landed in Opa-Locka and Miami, Florida, but a reporter discovered the bomber's guns had been taped and could not have been fired. Kennedy refused to allow any more bombings out of fear of the U.S. role being discovered, and as a result half of Castro's air force — and most of his army — stayed intact.

The bombings laid bare the CIA plans for invasion to Castro, who immediately staged a large rally and started arresting thousands of suspected dissidents.

American CIA agents fired the first shots

Even though President John Kennedy wanted to reduce the visibility of American forces involved in the Bay of Pigs invasion, there were actually several CIA agents who landed with the Cuban exiles on the Playa Girón beach, including Grayston Lynch and Rip Robertson (per John Prados in "Safe for Democracy"). On the morning of April 17, 1961, Lynch and Robertson, along with a group of over 1,000 Cuban exiles, made their way into the Bay of Pigs on board multiple ships and landing crafts. Local militia members stationed nearby noticed lights flashing on the beach, and drove towards the invaders in their army jeep. Lynch became caught in the headlights of the jeep and immediately started to open fire into the oncoming militia members. These were the first shots fired during the Bay of Pigs invasion.

The brief firefight caught the attention of the commander of the militia post, Comrade Mariano Mustelier, who immediately radioed news back to the headquarters of the army. Another CIA agent, Rip Robertson, landed elsewhere on the beach with another group of three Cuban agents, and they also got into a firefight with Cuban militia members. The element of surprise was gone, and now Castro was on full alert.

The expected popular uprising never happened

The CIA hoped that the invading forces of Cuban exiles would spark the popular uprising of citizens on their behalf, and they would all rally together to push Fidel Castro out of power (via Lawrence Freedman in "Kennedy's wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam"). Initially, the CIA expected around 3,000 people, aided by a further 20,000 sympathizers, to join the exiles, and they hoped as much as a quarter of the entire population would also show support, after seeing a professional fighting force. The invaders carried enough supplies for an estimated 30,000 recruits.

However, the invasion was such a complete failure that no popular uprising occurred, and no one came to aid the exiles against the Cuban army. Nobody had told many of the leaders of dissident Cuban groups that the invasion was coming, so none of them were prepared to aid the exiles. Castro's security forces also immediately rounded up as many as 100,000 people thought to be potential sympathizers, thus depriving the invaders of even more potential recruits.

The invading troops wound up trapped behind enemy lines

On April 17, 1961, the paramilitary task force of 1,400 troops landed on the Playa Girón beach in the Bay of Pigs. The bombings from the previous days had only been partly effective, and Fidel Castro's military was waiting for them. According to Lawrence Freedman in "Kennedy's wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam," the forces struggled to make it ashore amid the thicket of coral reefs, and they faced fire from Castro's forces. Cubans sank the CIA's freighter, the Rio Escondido, which was carrying 10 days' worth of ammunition, food, medical supplies, and communications equipment.

By the following morning, the exiles were outgunned and in serious trouble. By April 19, the CIA and Navy were concluding that, without substantial American support, the invasion was going to be a complete failure. Without any support from American troops, or any more serious bombing campaigns, the exiles became trapped in Cuba. The refusal of the Kennedy administration to help the exile force, that they had launched, deprived them of any potential backup or relief. As a result, Castro's army slowly started to constrict around the isolated exiles, trapping them, and cutting off any escape routes back.

JFK wanted plausible deniability

The CIA's last review of the invasion plans, during the Eisenhower administration, presumed that any president willing to launch the invasion would also need to be prepared to "to do everything else needed overtly or covertly ... to guarantee success." (via Lawrence Freedman in "Kennedy's wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam"). However, when the Kennedy administration took over in January 1961, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Secretary of State Dean Rusk both expressed hesitation over any overt U.S. role in the plan. As a result, Kennedy changed the course of planning to reduce any appearance of public U.S. support for the invasion. He wanted plausible deniability, or the idea that the U.S. could convincingly argue that they did not have any prior knowledge about the invasion.

John Prados argues in "Safe for Democracy" that Kennedy's obsession with plausible deniability, and his decision to reduce the "visibility" of the operation, led many to blame him for its failure. The initial plan called for a daytime landing, but Kennedy insisted on a midnight landing because it would be more secretive. A daytime landing would have been easier for the invaders, goes the argument, and Kennedy's decision to force a nighttime invasion effectively reduced their chances of victory.

The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations unknowingly lied

The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations (U.N.) in 1961 was the former governor of Illinois Adlai E. Stevenson II (pictured above). According to the Library of Congress, Stevenson had been a part of the initial U.S. delegation that drafted the original U.N. charter in 1945, and then served as a delegate for the next two years. Stevenson was only vaguely aware of the Bay of Pigs plan, even though he was a cabinet-level member of the Kennedy administration.

At the time of the invasion, Stevenson was, ironically, at a United Nations General Assembly debate concerning Cuban allegations that the U.S. was secretly trying to overthrow Fidel Castro's government. During the debate, Stevenson hotly denied any CIA plans for invading Cuba, such as the ongoing Bay of Pigs invasion. At an emergency meeting on April 15, the day the CIA-trained exiles started bombing the Cuban airfields, Stevenson argued the CIA line that the planes were piloted by Cuban defectors, not exile forces. He even unknowingly presented a doctored photo showing a plane with Cuban air force insignia as evidence.

In "Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA," Tim Weiner argues that CIA agents Richard Bissell and Tracy Barnes "played Stevenson for a fool," by getting him to peddle their lies about the invasion. When Secretary of State Dean Rusk heard the news, he was furious with the CIA.

American pilots died during subsequent rounds of bombings

The Bay of Pigs invasion began on the morning of April 17, 1961, but by the morning of April 18 the invaders were already in deep trouble. National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy started to pressure President John Kennedy to order more air strikes, to "eliminate the Castro air force" (via Lawrence Freedman in "Kennedy's wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam"). Kennedy demurred, and then decided against them after Russian Premier Nikita Khrushchev released a statement condemning the invasion, and promising Soviet support for the Cuban people.

Later that evening, the CIA kept pressing for more airstrikes to destroy the Cuban air force and heavy artillery, to allow the invaders to have a fighting chance. Eventually, Kennedy relented, and allowed for a limited operation involving six aircraft to cover air drops that were already planned. However, the planes arrived an hour late and several were shot down by the Cubans, leaving the invaders to be crushed within hours (per the JFK Library).

During the invasion, Americans piloted many of the planes flown over the Bay of Pigs, and two of them were shot down by the Cuban army. Riley Shamburger, Wade C. Gray, Willard Ray, and Leo F. Baker all died in a war that the Kennedy administration refused to acknowledge Americans were ever involved in (per John Prados in "Safe for Democracy"). They were fighting against the Cuban air force, which had been left intact because of scuttled bombings earlier in the campaign.

Despite the failed invasion, JFK's approval ratings climbed

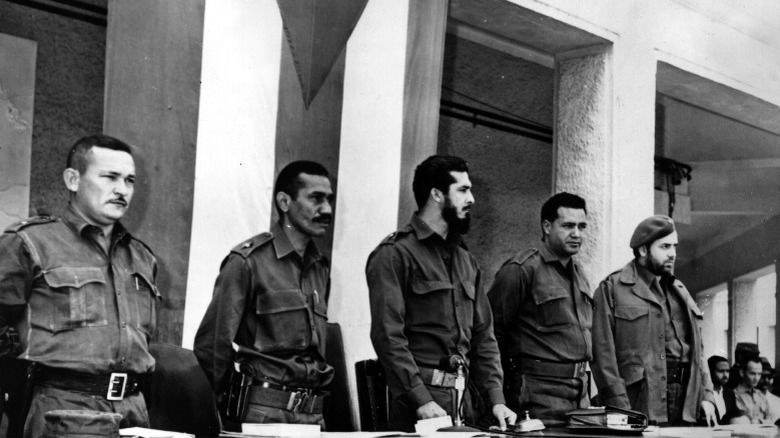

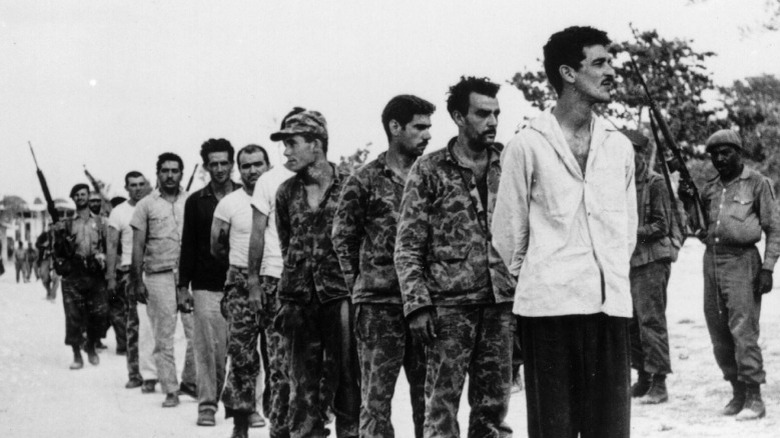

By the night of April 19, 1961, the invasion was over and the exiles were surrendering in droves (per Lawrence Freedman in "Kennedy's wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam"). By the end of the invasion, 140 exiles were dead, killed by misadventure or Cuban armed forces, and 1,189 were taken prisoner (pictured above). The planned uprising of dissident Cubans completely failed, and no general rebellion took place. The exiles remained in Cuban captivity for nearly two years, while Washington and Cuba worked out a deal. Eventually, 20 months later, they were released in exchange for $53 million in baby food and medicine for the Cuban people (per the JFK Library).

In the end, both Richard Bissell, head of the clandestine department of the CIA, and Allen Dulles, the director of the CIA, lost their jobs as a result of the failed invasion. Yet, somehow, President John F. Kennedy's approval rating shot up 10 points to an incredible 83%, prompting him to remark, "The worse you do, the better they like you."