Why Haven't We Landed On The Moon Since 1972?

Humanity has been dreaming of the moon ever since wonder awoke within us. The allure of its silver surface has always called to us, inspiring writers to tell tales of traversing the ether between worlds. The earliest story we know of goes back to the second century A.D. and imagines Greek mariners being spirited to the moon on a giant waterspout (via Astronomy).

As technology and our understanding of the universe progressed, our stories grew closer to the impending reality. In his 1865 novel "From the Earth to the Moon," Jules Verne imagined some of the logistics involved in a trip to the moon, including launching from Florida and landing in the ocean via parachute (via ZME Science). In his 1950 novel "The Man Who Sold the Moon," Robert A. Heinlein imagined the massive costs and the mercurial nature of public opinion.

Even today, over 50 years since we first landed on the moon, movies like "Moon" and TV shows like "The Expanse" continue to imagine what our life would be like on our silver satellite, which raises the question: If we're so fascinated with the moon, why haven't we been back since 1972?

The Apollo program

The race to the moon officially began in 1961, when President John F. Kennedy addressed a joint session of Congress, setting out his goal of landing a man on the moon (per the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum). This doesn't sound like an ambitious goal today, but consider that Sputnik — the first man-made satellite — was launched in 1957 and Yuri Gagarin — the first man in space — made his first Earth orbit barely a month before Kennedy's speech (via Royal Museums Greenwich).

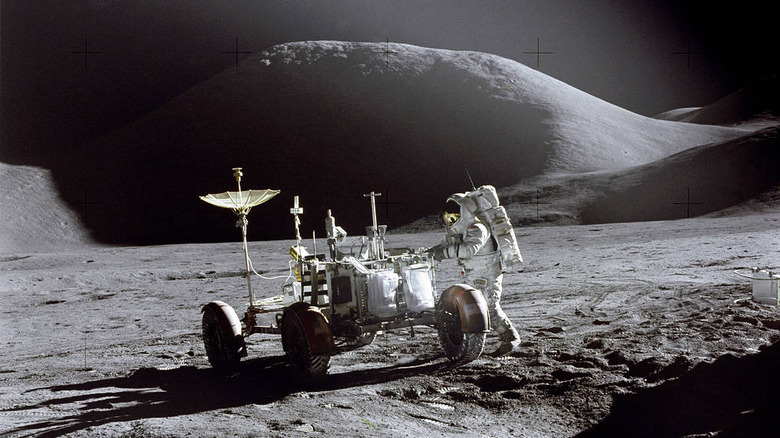

The Apollo space program officially began in 1967, and by 1968 the Apollo 8 mission had sent three men around the moon and safely back to earth. And on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to walk on the moon. Over the next three years we went back five more times, putting a total 12 humans so far on the lunar surface (per NASA).

For eight ambitious years, we strove for the moon. Even in the face of tragedy — Kennedy was assassinated in 1963 and the Apollo 1 crew was killed in an accident (also via NASA) — the will of the American people and the momentum of Kennedy's ambition was enough to see the program through to completion. But then we didn't go back.

The moon after Apollo

That is to say, so far, no human has returned since Eugene Cernan left in 1972 (per Space.com). The Soviet Union's Luna program initially operated from 1959 to 1976, bringing back lunar samples and testing orbital maneuvers (via Popular Mechanics). Russia currently has plans to revive the program with the launch of Luna 25 next month (per NASA).

India was the next country to "touch" the lunar surface in 2008 when it released an impactor as part of the Chandrayaan-1 mission (per NASA Science) which helped to confirm water on the moon's surface. The China National Space Agency has successfully landed three rovers on the lunar surface, two of which are still operational, and one of them — Chang'e 5 — has successfully returned samples of the lunar surface (per The Planetary Society).

The private Israeli space company SpaceIL and the Indian Space Research Organisation have both attempted to land rovers on the moon, but both of those attempts were unsuccessful. The SpaceIL lander — Beresheet — crashed after an engine failure (per BBC), and ISRO's lander Vikram crashed after a similar problem (per another post at Space.com).

Going to the moon is expensive

The original plan for the Apollo missions was for 20 missions: 10 preparatory missions and 10 to the moon and back. Once we landed on the moon, however, the political will that had put us there seemed to falter. Fewer than six months after Apollo 11 made its historic discovery, Apollo 20 was canceled. Two more Apollo missions were canceled later that same year, all due to a lack of money (via NASA).

According to The Planetary Society, NASA's budget peaked in the mid 1960s at over $58 billion dollars (adjusted to 2022 dollars) as the technology to get men to the moon was initially developed. By 1970, after the first moon landing, its budget was nearly cut in half, to $30 billion. Still, all told, NASA spent over $250 billion on just the Apollo program from 1960 to 1973 (also via The Planetary Society).

And the moon wasn't NASA's only scientific goal. One year after we left the moon for the final time, NASA used the rocket designed to take us there to launch the U.S's first space station (also via NASA). And in 1969, planning had already begun for what would become the Space Shuttle program (via Scientific American).

Potential political perils

Going to the moon wasn't just financially expensive, it was potentially politically expensive as well. NASA's budget is set by Congress, and getting to the moon cost billions of dollars, which isn't an easy sell to constituents. Nor is the loss of human life. The Apollo program almost ground to a halt after the Apollo 1 disaster, and President Richard Nixon was prepared to give a speech mourning the loss of Apollo 11 in the face of a potential disaster (via the National Archives).

And contrary to many popular narratives, there was never a lot of public enthusiasm for going to the moon. Historic polls show that public support for lunar exploration only rose above 50% once. Support for the Apollo program peaked at 53% right after the Eagle lander touched down in 1969. Polling shows that Americans only support the space program when they divorce it from its budget. Despite only accounting for around 4% of the national budget at the peak of NASA funding in 1964, most people wrongly estimate its funding to account for over 20% of the national budget (via Space.com).

Given that the public thinks it's too expensive, and the need for the political symbolism of being first to the moon has long passed, it's no wonder that NASA has used its limited budget and political clout on unmanned missions and sending humans to the relatively safe confines of the International Space Station in low-Earth orbit.

A potential return

Going to the moon is hard, it's expensive, and it isn't always popular. Despite that, three successive presidential administrations have spent political capital getting the Artemis program off the ground. Artemis (the sister of Apollo) was started under President Trump in 2017 and aims to bring humans back to the moon by 2026.

NASA is currently testing the Space Launch System rocket — the most powerful ever built — which will take the next generation of explorers to the moon. The Artemis 1 unmanned mission is currently slated to launch in August (per Space.com) and will serve as a dress rehearsal for the Artemis 2 crewed mission in 2024. Artemis 3 is planned to land two people on the moon in 2026 (also per Space.com).

There's still a lot of work left to do for these missions to get off the ground. NASA is still testing the SLS rocket needed to get to the moon (per Ars Technica) and delays in space suit design (via The Verge) have pushed the dates back even further. But if all goes to plan, NASA will not just have sent humans back to the moon, they will have established semi-permanent structures on the lunar surface and in lunar orbit to facilitate future manned lunar exploration (via NASA).