Civil War Myths You Always Thought Were True

You probably think the American Civil War ended in 1865, but it only sort of did. Today, more than 150 years after the North and South stopped fighting each other, we're still bickering about the details. Some facts aren't in dispute — with more than 620,000 Americans dead, the Civil War beats out World War II by more than 200,000 casualties as the bloodiest war in American history.

The motives, history, and facts of the Civil War are still hotly debated, and one of the probable reasons for all the disagreement is because it's difficult to really comprehend why so many people had to die. As General Ulysses S. Grant famously said, "That cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse." So it's not really surprising that some people prefer to think the war was about state's rights, and maybe slaves didn't really mind being slaves. Except none of that is true. Here are a few of the most-believed Civil War myths and the real truth about that awful time in American history.

Fighting for the right to be enslaved

There is one strange and persistent Civil War myth that African-Americans fought for the Confederacy, presumably because they believed in the cause. If you think the whole idea sounds ridiculous that's because it is. In fact History says that there was an official Confederate Army prohibition against blacks serving in the military. That prohibition lasted until March 1865, just one month before Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Virginia.

That's not to say Confederate officers never considered pressing blacks into service (essentially, forcing slaves to fight for a cause that was clearly not in their own interests). In 1864, Jefferson Davis not only rejected the idea, he also said he never wanted it brought up again. But toward the end of the war, when Lee was getting desperate for able-bodied soldiers, the Confederate leadership finally decided they were out of options and implemented a program that would allow black men to fight in exchange for freedom after the war. One example was Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, who took upwards of 45 of his own slaves into several battles, reports the Times News.

Slavery? What slavery?

Over the years a new theory about the root cause of the Civil War emerged, mostly in places where people still kind of like flying the Confederate flag but think the whole slavery-as-cause-of-Civil-War thing is too icky.

In a way, the reasons behind the argument (that the Civil War was actually about state's rights and not about slavery at all) make a certain kind of sense. Southerners, like everyone, want to view their history and heritage with pride, and that's pretty hard to do when that history and heritage has a deeply ugly side to it.

But the real cause of the Civil War has never really been under dispute. According to historian James Oliver Horton, the evidence comes directly from historical documents such as letters and speeches, many of them written by Confederate leaders and supporters. South Carolina's Charleston convention specifically blamed "the non-slaveholding states" and their refusal to enforce the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act as one of its reasons for secession, along with the election of Abraham Lincoln, "whose opinions and purposes are hostile to Slavery." So on some superficial level you could say the war was about "state's rights," but that's a little bit like saying that the Battle of Little Bighorn was about mineral rights. Yes, the United States government ultimately wanted all that Black Hills gold, but the larger issue was that they didn't care who they had to stomp all over to get it.

Who needs morphine when we've got this perfectly good chunk of wood?

One of the most cherished modern images of the Civil War is the wounded soldier with a chunk of wood between his teeth, waiting for the surgeon to saw off his leg. It makes for pretty great television, especially if you have an unrequited sadistic streak, but it's largely untrue.

According to research from Ohio State University, amputation was the most common battlefield surgery, not because bloodthirsty surgeons over-diagnosed the need for it, but because of the adorably-named "Minie ball" everyone was getting shot with. The Minie ball caused horrific injuries — if you were shot in the head or body, you died. If you were shot in the arms or legs, you got an amputation, and you might die anyway. The mortality rate for hip amputations was about 83 percent. If you were lucky enough to have only part of your arm blown away, your chances of dying improved to 24 percent.

Surgeons didn't sterilize equipment, they wore blood-splattered coats, and they didn't wash their hands. But they weren't butchers or anything. Amputees-to-be were blissfully free of consciousness during the procedure — the surgeon would administer chloroform and then do his work quickly, so (hopefully) when the chloroform wore off he would be busily sawing someone else's limb off. That's not to say losing a limb during the Civil War wasn't deeply sucky, but at least anesthesia was more than a shot of whiskey and a chunk of wood.

The Gettysburg address was not written on an envelope

Americans love the image of Abraham Lincoln sitting on the train, jotting down his final thoughts for one of the world's most epic speeches on the back of an envelope — just like they love the story of George Washington and the cherry tree and Richard Gere and the gerbil. Except that none of those stories are true. (Sorry.)

The origins of the story of Lincoln and the envelope are uncertain, but logic can pretty much rule it out. Nineteenth-century trains weren't exactly smooth riding, so trying to jot something down on an envelope mid-journey would have been at best impractical and annoying. It's also kind of hard to believe that Lincoln would have been writing the entire speech at the last minute. In fact if you spend some time studying the historical record (which you'd have to be pretty bored to do if your goal is to just work out what sort of stationery Lincoln used to write the Gettysburg address, but whatever) ThoughtCo says you'd find at least two people who would testify to the fact that the address was written in Washington D.C. before Lincoln got on the train. Which matters, for some reason, though no one is really sure why.

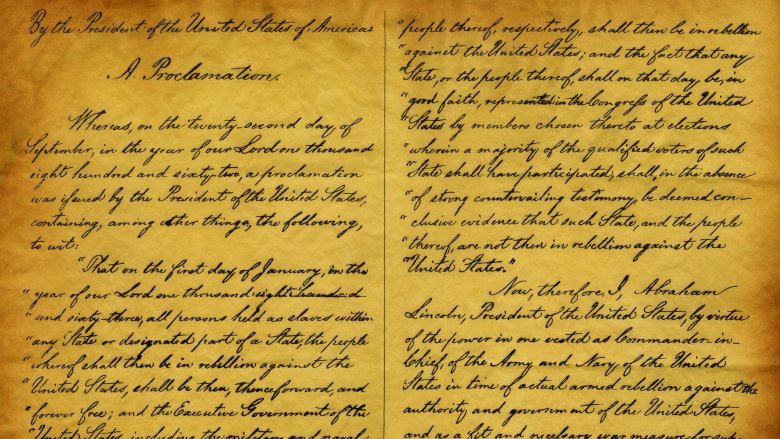

Emancipation but not necessarily for everyone

Wouldn't it be great if the Emancipation Proclamation of 1862 had ended slavery, and then all Americans became free and equal and we lived in peace and harmony from there on? And as long as we're wishful thinking, wouldn't it be great if slavery had never been a thing at all and there was never any need for an Emancipation Proclamation? Well, history is pretty danged cruel because none of those things happened. The Emancipation Proclamation didn't actually free all the slaves, and we're still waiting for everyone to be treated as equals.

According to the Civil War Trust, the Emancipation Proclamation was not intended to be a statement of the right for all people to be free; it was really just a military strategy. It only applied to the states that were in rebellion, which means slaveholding states that weren't part of the Confederacy got to keep their slaves. Confederate states, on the other hand, weren't allowed to have slaves anymore which also meant they couldn't have slaves carry their military stuff around or cook their meals or polish their boots, so you know, it was pretty crippling.

It wasn't until three years after the Emancipation Proclamation, at the end of the war that the 13th Amendment abolished slavery everywhere (except prisons).

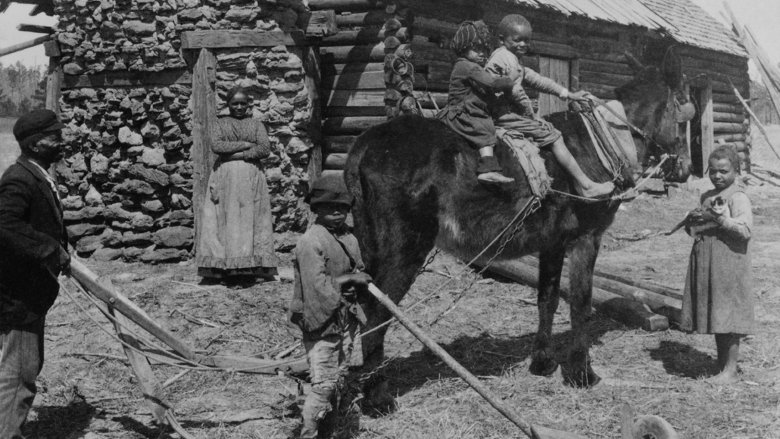

But they like it here

One of the more obnoxious Civil War myths is the strange notion that slaves didn't really want to be free, which is sort of like saying that a well-fed bird should be perfectly happy sitting in a cage.

This argument seems to claim that slaves woke up every morning eager to do the bidding of their benevolent masters in exchange for an "atta boy," which is a statement that looks a lot like a puddle of verbal vomit when you see it written down. Now, there might have really been some "benevolent" slaveholders who treated their favorites well, but you know what they say about birds in gilded cages. All the kind words in a puddle of verbal vomit don't change the basic structure of that relationship. Slaves wanted to be free — if they didn't, there wouldn't have been so many runaways.

According to the Civil War Trust, many slaves lived in brutal conditions. They were routinely whipped, and families were often separated when slaveholders would trade or sell them to other slaveholders. And because that's not awful enough, in 1857 the United States Supreme Court declared slaves to be legally not-human, which meant they had no right to object to the brutal conditions they lived in, no right to seek justice, and no right to love and protect their own children. So the whole "the slaves didn't want to be free" thing is not only completely untrue, it also defies logic.

Some people are more equal than others

The Union fought against the institution of slavery, but does that mean Northerners viewed blacks as equals? Nope. Northerners were mostly cool with the idea of free blacks, but free blacks that could vote, hold office, sit on juries, or marry white people? Heavens! Let's just say that even in the North, there was a lot of swooning and pearl-clutching going on after emancipation.

According to historian Douglas Harper, free blacks were still second-class citizens, prohibited from testifying in court, voting, assembling, or doing things that might make white people behave like idiots. This was true before the Civil War as well as after it, and it didn't even have to be written into law. In 1831 French sociologist Alexis De Tocqueville asked why Philadelphia blacks didn't vote when there was no law prohibiting them from doing so, and was told "The law with us is nothing if it is not supported by public opinion." In other words, "We'd love to vote, but if we did then white people would act like idiots." Some places didn't even let free blacks cross their borders. In Illinois, visiting blacks who stayed for more than 10 days would be charged with a high misdemeanor. "Equality" for anyone who didn't have white skin was not something most white Americans believed in even philosophically, and wouldn't be for decades.

And they all rode off into the sunset

So slavery ended, and then everyone lived happily ever after. Except no, because although you can legislate freedom, you can't legislate people out of being ignoramuses. After the Civil War ended, most people's opinions stayed the same. Those who believed blacks were subhuman continued to feel exactly the same way, and so were not inclined to do things like allow them to have jobs, food, or medical care.

According to historian Jim Downs, up to 25 percent of the 4 million people freed from slavery died of starvation or diseases like cholera and smallpox. But no one ever talked about it because anyone who felt that blacks were less than whites really couldn't be bothered to care. In other words, they fought like hell to make sure no one in America would ever live in slavery, but when it was all over they were all, "We've done enough here." And abolitionists didn't talk about it either because one of the principal arguments against freeing the slaves had been that freed slaves wouldn't be able to care for themselves. (Without leveling the playing field, of course it would be difficult for them to do so.) And so began decades of racism and white privilege. Hooray for America.

Because my dishonor is way worse than other people dying

General Robert E. Lee has been called "a great son of the South," a "noble patriot," and a dude you might want to have dinner with, but how much of that is a reflection of the real man, and how much is just wishful thinking? According to the Washington Post, Lee claimed after the war that he "could have taken no other course without dishonor," which was basically like saying, "All those dead people? Totally not my fault, 'cause if I hadn't played my part in the rebellion someone might have thought it wasn't cool."

Most historians do agree that Lee was a brilliant tactician, but from there opinions diverge pretty significantly. Lee was a slaveholder, he regularly separated his own slaves' families by selling them to other plantations, and his army was known to capture free blacks in the North and sell them to slaveholders in the South. And just in case you're still in doubt, he once claimed freeing the slaves was un-Christian: "Based on wisdom and Christian principles you do a gross wrong and injustice to the whole negro race in setting them free." Ye-ep.

Wait, you mean the war is over?

General Lee's surrender is another one of those moments in history that started as something that happened in a room and grew into something that happened in a fantasy novel from the 1980s, except without the unicorns. There was the laying down of arms ceremony that Grant totally blew off because he had occupations to plan, and the ceremonial sword that Lee handed over to Grant that Grant refused to take (which never actually happened), and then there was the whole war-ending thing, which also didn't happen, at least not for more than a year.

According to the National Archives, Lee did surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, but that was not the end of the Civil War. Many Confederate leaders weren't ready to surrender, so they didn't. The last engagement of the Civil War was more than a month after Lee's surrender. And in August at least one Confederate ship was still attacking Union ships because evidently no one told the crew hostilities had ended. It wasn't until a full year after that when President Johnson declared a formal end to the conflict. And after the war some states were still in a pseudo-state of rebellion — Georgia was under military rule until 1871, and former Confederate soldiers killed as many as 50,000 freed slaves before the turn of the century. Where are those unicorns when you need them?

The battle cry of decent footwear

There's also a fun idea about the Battle of Gettysburg being over shoes and/or a shoe factory, which would make it sort of like Black Friday at Famous Footwear only with muskets and buglers.

According to the Civil War Trust, the problem with this particular story is that it seems to have first appeared 14 years after the battle. The originator of the story was a Confederate general named Henry Heth, who wrote, "Hearing that a supply of shoes was to be obtained in Gettysburg, eight miles distant from Cashtown, and greatly needing shoes for my men, I directed General Pettigrew to go to Gettysburg and get these supplies." Which was cool, except that in 1863 there were no shoe factories in Gettysburg, or anywhere near the vicinity, so it's unclear where Pettigrew was supposed to obtain the shoes unless there really were plans to raid a Famous Footwear.

The shoe myth probably got legs from the fact that Civil War soldiers on both sides were famously shoe-deficient and Generals would often order vanquished townships to hand over supplies, including footwear. Less than a month before the battle, General Jubal Early tried to acquisition 1,000 pairs of shoes from Gettysburg but got only the sorts of shoes that you put on horses, which wouldn't have really done his "shoeless and footsore" soldiers a whole lot of good. Still, people do love their footwear, so this is one legend that won't wear out.

The noble Code of the Hoof

After the war (sometimes years after) people erected statues of Civil War generals, maybe so 150 years later we'd all still have something to fight about, along with all the other Civil War myths. Meanwhile, observers started to notice that sculptors sometimes put generals on horses with raised hooves and sometimes on horses without raised hooves and they thought to themselves, "Hmm, there must be some significance to all this hoof-raising." And then someone noticed that generals who were killed in battle were depicted on horses with two raised hooves, and generals who were wounded were depicted on horses with a single raised hoof, and generals who survived were depicted on horses standing firmly on the ground. Thus was born the honorable Code of the Hoof, which wasn't actually called that because it was never really a thing.

While it is true that you will find some equestrian statues that seem to follow the Code of the Hoof, Ohio State University promises it's all just a coincidence. There are no sculptors who can recall following any kind of code when they decided on a hoof position. Most of them say they were simply trying to recreate a moment or capture the subject's personality, and so they chose to place that person on a standing horse, or a prancing horse, or a rearing horse, and thus let the hooves fall where they may.