The Untold Truth Of Abraham Lincoln

Everybody knows Abraham Lincoln. His face is plastered on the penny and chiseled on Mt. Rushmore. He's been portrayed in movies by actors like Henry Fonda and Daniel Day-Lewis. There are statues of the guy in countries like Mexico, England, Cuba, and he's even got his own Walt Whitman poem. With his iconic top hat and epic beard, the 16th president is one of the most fascinating Americans who's ever lived and a man with a rich history of unbelievable, untold truths.

Lincoln the militiaman

Long before he was commander-in-chief, Lincoln got first-hand military experience during the 1832 Black Hawk War. The conflict started when the Native American Chief Black Hawk (pictured above) started butting heads with the US government. White settlers were taking Black Hawk's turf, and when the chief got angry, the Illinois governor called up a militia, summoning 1,500 men for battle.

One of those guys was 23-year-old Abraham Lincoln, who was elected captain of his company, a moment he later described as "a success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since." However, Lincoln had a difficult time at first keeping his men in line. When he started giving orders, his troops responded with insults like, "Go to the devil, sir!" On another occasion, his company got so drunk on stolen liquor that they couldn't march, so Lincoln was forced to carry a wooden sword for two days (instead of a real one) as punishment.

Lincoln disobeyed orders himself on another occasion, firing his weapon within 50 yards of camp. As a result, he was arrested and stripped of his saber for 24 hours. Despite these setbacks, Lincoln was considered a good soldier with a solid sense of right and wrong. When a Native American walked into camp looking for a job, Lincoln's men wanted to shoot the interloper, but Abe intervened, telling his men to stand down. When they called him a coward, Lincoln responded, "If any man thinks I am a coward, let him test it."

Naturally, nobody was willing to throw down with Lincoln, who spent his free time competing in wrestling matches. However, even though he reenlisted with the militia two more times as a private, Lincoln never saw any combat, although as he later explained, he did have "a good many bloody struggles with the musquetoes [sic] and, although I never fainted from loss of blood, I can truly say I was often very hungry."

His odd connection to the Donner Party

Don't be fooled. Just because it's called the "Donner Party," that doesn't mean people were having any fun. This 1846 wagon train famously got stuck in the snowy Sierra Nevada mountains, and the hungry settlers were forced to partake of their fellow pioneers. Of the 87 people who left Illinois for California, only 48 made it out alive. While this expedition is closely associated with cannibalism, it also has some crazy connections to America's 16th president.

In 2010, historians discovered four muster rolls—registers of troops in military units—among the possession of James Reed, a Donner Party pioneer (pictured above). This Illinois businessman was kicked out of the expedition after stabbing a dude to death, but Reed's wife stayed with the train, carrying the papers to California. Decades later, researchers looking over the rolls noticed Lincoln's name listed alongside Reed's, as the two men were friends who'd served together in the Black Hawk War.

Reed had gotten a hold of the muster rolls and probably kept them for personal reasons. But in addition to spotting Lincoln's name, the researchers also noticed that Lincoln had written a few lines on the document himself, describing how Captain Jacob M. Earleys had been mustered out of the militia on July 10, 1832. Lincoln's handwriting had traveled through the Sierra Nevada mountain range and made it through intact, while most of the people involved were turned into pâté.

This isn't Lincoln's only connection to the Donner Party, though. According to historian Michael Wallis, Abe had actually considered going with Reed to California, but his wife, Mary Todd, was pregnant and Lincoln was getting started in politics, so the couple decided to stay in Illinois. However, as the Donner Party pulled out of Springfield, Illinois, Mrs. Lincoln was actually there to send them off.

Abraham Lincoln's bar

Lincoln held quite a few jobs over the course of his life. He was a boatman, a surveyor, a post office clerk, and—before moving into the Oval Office—Lincoln ran his very own bar. He started this intoxicating career in 1833, opening a store in the town of New Salem, Illinois. The business was called Berry and Lincoln, borrowing its name from Abraham and his business partner and militia buddy, William F. Berry.

If you were to drop by Berry and Lincoln, you could grab all sorts of goods, from bacon and guns to beeswax and honey. Then in March 1833, the duo obtained a tavern license, which meant people could buy and consume alcohol on the premises. (In old-timey parlance, their establishment was now called a "grocery," a store that doubled as a bar.) According to Chicagoist, patrons could buy half a pint of apple brandy for 12 cents, rum for 18.75 cents, and wine for a quarter. There was French brandy, peach brandy, and whiskey, and after you were done drowning your sorrows, you could get yourself a room for the same amount it took to buy a glass of domestic gin (12.5 cents).

Unfortunately, the bar wasn't very profitable, and Berry spent most of his time siphoning off the supply. The two owners soon found themselves in debt, and Lincoln sold Berry his share of the business. However, Lincoln's career choice dogged him for quite awhile. During the Lincoln-Douglas debate, Stephen Douglas slipped in a joke or two about Lincoln's alcoholic occupation, and despite his nickname of Honest Abe, Lincoln did his best to play it down, denying he'd ever run a "grocery."

He was an inventor

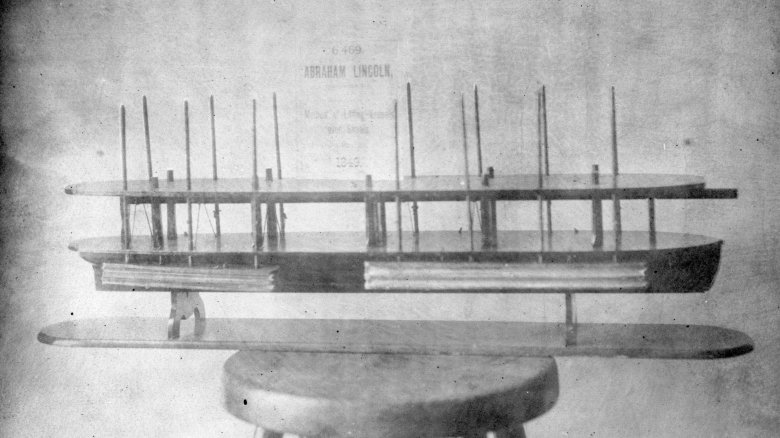

Lincoln was a man of great accomplishments. He freed the slaves. He preserved the Union. He delivered the Gettysburg Address. In addition to all that, he's the only president to ever hold a patent in his name.

The man decided to get all inventive after he took a series of boat trips that wound up with his ship getting stuck on sandbars. This was particularly annoying as, most times, you had to unload everything so the boat would be light enough to lift up and float downstream. But Lincoln was inspired after watching a captain tie empty barrels to the side of his ferry (thus buoying the steamboat over an obstruction), and the future president then dreamed up a device to prevent anymore ships from running aground.

Lincoln's invention involved chambers made of waterproof fabric that were attached to the side of a ferry. You could lower or raise the chambers with a system of ropes and pulleys, and if you ever hit a snag, you could inflate these chambers, allowing the boat to keep on moving like nothing had ever happened.

To get his point across, Lincoln actually had someone build a little model of a ship—complete with the buoys—and he took out a patent in May 1849. However, the device never took off, and instead of becoming a world-famous inventor, he wound up putting his creative brain to work in the White House.

The almanac alibi

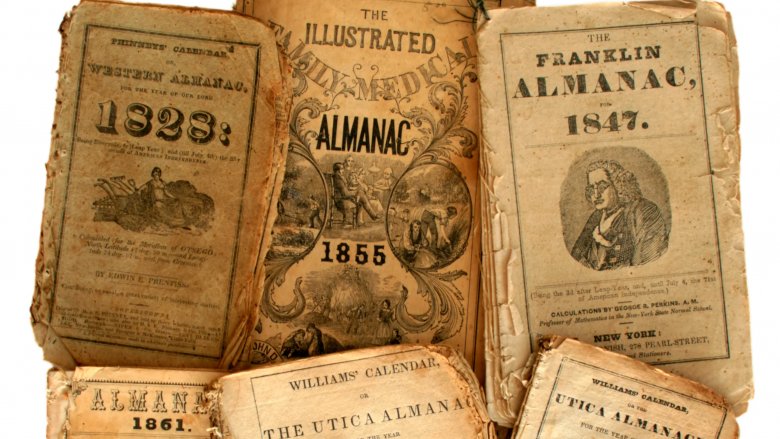

Before jumping into the national spotlight, Lincoln was probably best known for defending William "Duff" Armstrong in an 1858 murder trial. Armstrong was accused of killing "Pres" Metzker with a blackjack-type weapon, and things weren't looking good for the Duff. His associate, James H. Norris, had also been accused of the crime, and he'd just been tossed into the slammer for six years. Now, Armstrong was facing a jury of his peers, but fortunately Lincoln was a family friend and offered to defend Duff for free.

The entire case hinged on Charles Allen, a witness who swore he'd seen Armstrong and Norris beat Metzker to death. Sure, it was 11 o'clock at night, and yeah, he was standing 150 feet away, but Allen claimed the moon was big and bright enough for him to clearly see the killing. Lincoln shot this argument down by providing the court with several copies of a farmer's almanac, showing that at 11 p.m. on the night in question, the moon—only in its first quarter—would've been on the horizon, not overhead.

If the moon was so small and so low, how could Allen have witnessed the murder? The tactic paid off, and Armstrong walked away a free man...although this savvy move might've hurt Lincoln's short-term political goals. When Lincoln ran against Stephen Douglas for a US Senate seat, the pro-Douglas faction claimed that Lincoln had used an altered almanac to get his guilty client off the hook.

However, the chances that Lincoln printed up a bunch of fake pamphlets are pretty slim. Multiple modern-day astronomers have verified Lincoln's claim, and during the trial itself the prosecutor double checked Abe's argument by buying his own almanacs just to make sure everything was on the up-and-up. It seems Lincoln's copies were unaltered, and as the old saying goes, if the moon isn't lit, you must acquit.

Lincoln's controversial opinions on freed slaves

While Lincoln deserves praise for ending slavery, it's important to remember the 16th president was just a human being, a complex person with real flaws and ever-evolving opinions. So it should come as no surprise that Lincoln's views on emancipation changed quite a bit during his time in Washington. While the president always believed slavery was wrong, he wasn't always so sure about what to do after destroying the peculiar institution.

At first, Lincoln believed that slavery should end gradually, over a period of time instead of in one fell swoop. And for quite awhile, the Great Emancipator thought free African-Americans should pack their bags and move overseas. Lincoln was quite the believer in colonization, and he thought black people should sail to Liberia—a country founded by liberated slaves—or perhaps spread America's influence by starting up their own societies in South or Central America.

In fact, Lincoln was such a proponent of this colonization idea that he invited a bunch of black leaders to the White House in hopes of convincing them to move to countries like Brazil or Colombia. Congress even amassed a sizable chunk of cash to help with the move. Of course, this idea didn't fly and eventually, Lincoln began to change his mind about immediate emancipation and integration. And then in July 1864, Congress forever ended the use of federal money to create colonies, ensuring the United States of America—despite plenty of setbacks, even to this day—would slowly but surely morph into a country of equal rights for all.

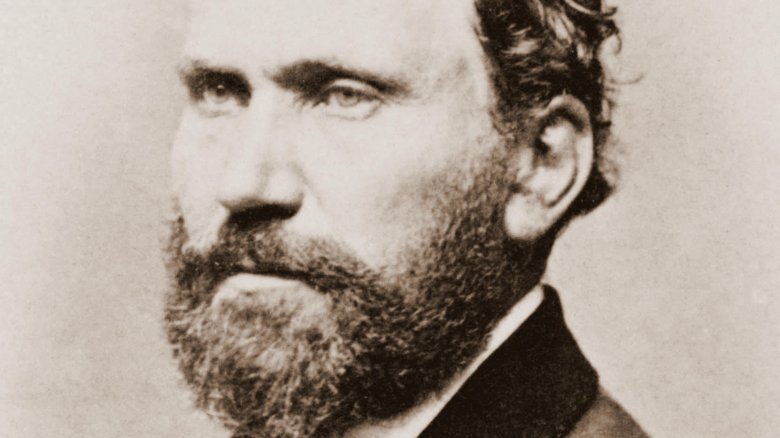

The Baltimore Plot

Lincoln's presidency got off to a shaky start when he received word about a possible attempt on his life. Allan Pinkerton—head of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency (pictured above)—had been working undercover in Baltimore and had reason to suspect a group of secessionists were planning to permanently impeach the president.

Having spent time working in anti-Lincoln circles, Pinkerton and his agents suspected a barber named Captain Cypriano Ferrandini of plotting Lincoln's death. According to the private eye, the cutthroat crew would strike when Lincoln stopped in Baltimore on his way to the White House. The killers knew exactly when Lincoln would arrive as he'd published his schedule for everyone to see. Even worse, when Lincoln arrived in Baltimore, he would be forced to switch trains by walking from one station to the other, exposing himself to gunfire.

Hoping to keep the president safe, Pinkerton quietly changed Lincoln's itinerary. Instead of arriving in Baltimore in the afternoon, he would arrive at 3:30 in the morning, showing up at a completely different train station than announced. And to make sure nobody could contact the assassins as Lincoln rode the rails from Pennsylvania, agents cut the telegraph lines between Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Once that was taken care of, Lincoln boarded a train disguised as an invalid. He was escorted during his trip by Kate Warne, America's first female detective, who pretended to be his sister while keeping an eye out for assassins. Then, after arriving at their destination in the wee hours of the morning, Pinkerton hooked Lincoln's train car to a team of horses, silently pulled him from one train station to another, attached the cab to a new locomotive, and sent Lincoln safely on his way.

Unfortunately, many were upset with Lincoln for sneaking into D.C. like a "thief in the night," considering his actions shameful, but hey, it's better to be end up disgraced than dead.

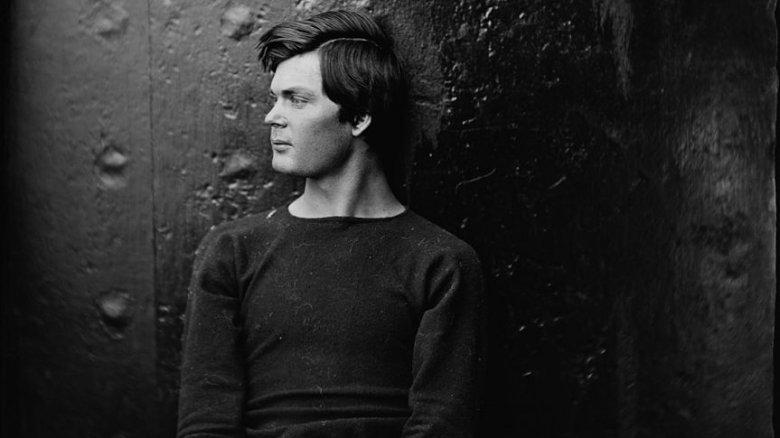

The assassination conspiracy

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln shook the US to its core, but that fateful day in April 1865 wasn't the first time John Wilkes Booth had tried to take out the commander-in-chief. Believe it or not, the actor had originally plotted—on two separate occasions—to kidnap Lincoln and exchange him for Confederate POWs. However, when the war ended, Booth decided to step up his game...but Lincoln wasn't the only name on his kill list.

Working with a group of Southern sympathizers, Booth planned on murdering Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William Seward. However, the thespian was the only one who successfully carried out his part of the plan. George Atzerodt was supposed to get Johnson, but he chickened out. And Lewis Powell (pictured above), the guy assigned to get rid of Seward, tried his bloody best, but things didn't pan out the way Powell expected.

When the Confederate soldier showed up at Seward's house, he slashed his way inside, wounding seven people, not including the secretary of state. When he finally reached the defenseless politician, Powell stabbed Seward multiple times. Fortunately for the secretary, he'd recently injured his neck in a coach accident, and his metal brace stopped Powell's knife from reaching his arteries.

Eventually, the conspirators were rounded up, and Atzerodt and Powell were sent to the gallows, along with David Herold and Mary Surratt, the first female ever given the death penalty by the United States government. Four other conspirators were tossed into prison, and as for Booth, the man was cornered in a barn and shot to death. Thus always to terrorists.

The bizarre journey of Lincoln's body

After his tragic and untimely death, Lincoln set off on one of the weirdest train rides in US history. In order to give the American people a chance to grieve their dead leader, it was decided that Lincoln's corpse would be sent on a 1,600-mile long journey from the nation's capital to Springfield, Illinois. Along the way, the president's casket would stop in nearly 200 cities across states like Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York, and whenever the executive train came to a stop, Lincoln's body would be put on display for the public to see. (Oddly enough, Lincoln was accompanied by his 11-year-old son Willie...who'd died of typhoid fever about three years before.)

The journey took fourteen days, and during that macabre train ride, Lincoln's corpse would be set up in public places like city halls. Sometimes his coffin would be open for a few hours, and sometimes he was left exposed to the elements for the entire day. Droves of people flocked to his casket, hoping to mourn and say goodbye, but even though he'd been embalmed, this postmortem parade wasn't doing Lincoln's complexion any favors. Soon, his skin began to change colors, and witnesses said his face had turned into "a ghastly shadow" of its presidential glory. But even when the train ride finally came to a halt in Illinois, Lincoln wasn't able to rest in peace just yet.

Kidnapping Lincoln's corpse

After Lincoln's ghoulish goodbye tour, the president was laid to rest at the Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois. He was set in a marble sarcophagus that was locked inside a tomb, although security around the site was a tad lax. There weren't any guards, and if you wanted to get in the mausoleum, all you had to do was pick a single padlock.

This was great news for Big Jim Kennally, a Chicago gangster who'd cooked up a truly crazy scheme. One of Kennally's top counterfeiters, Benjamin Boyd, was behind bars and the mobster figured if his men could kidnap Lincoln's corpse, then maybe they could bargain for Boyd's release. Better still, maybe they could also convince the government to fork over $200,000.

So in 1876, Kenally sent two of his goons, Terence Mullen and Jack Hughes, to do his dirty work. These guys also brought along a compatriot named Lewis Swegles, a man who actually worked as a mole for the Secret Service. Swegles let the feds know what was going down, and when the gangsters tried to make off with Lincoln's body, law enforcement was waiting right outside the tomb. Unfortunately, the crooks escaped, although they were picked up shortly afterward.

Worried about future grave robbing attempts, the man in charge of Lincoln's tomb (John Carroll Power) assembled five friends and, together, they buried the president's body in a secret location. This was far from the last time that Lincoln's corpse would be disturbed. Over the next few decades, his coffin was moved 17 times, and was even opened on a few occasions to make sure the corpse was still there. Thankfully for Honest Abe, the man was finally laid to rest in 1901, joining his wife and three of his sons inside the tomb that bears his name.