Widely Held Beliefs With Unbelievable Backstories

Ideas aren't called brainchildren for nothing. Human heads conceive them through hard work, and once those brain babies enter the world, the beliefs develop in relation to the people around them. Along the way, those ideas will either spawn new ideas with the help of minds that embrace them or die alone and unwanted. When ideas seem conceivable enough, people wed their brains to them. And just like human unions, those mental marriages will last until a more attractive option comes along or irreconcilable differences lead to divorce.

Basically, your brain is fickle-hearted. Also, ideas have lives of their own. The scientific traditions, religious doctrines, and political debates that guide societies to greatness or off a cliff have rich histories, some of which are ridiculous. So in keeping with the marriage comparison, let's pull a When Harry Met Sally and take a jog down memory lane to learn how some of our modern beliefs got to where they are. It won't be a very romantic trip, but you might find parts of it comedic.

Van Leeuwenhoek's explosive organisms

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek fathered microbiology during the 1670s, when scientists didn't fully know how men fathered anything. Amazingly, he had no scientific training. Van Leeuwenhoek lived in Holland, where he sold fabric, ribbons, and buttons, per National Geographic. During his downtime he came up with eyeglasses that outclassed every microscope on the planet in terms of magnifying ability. He then had a field day observing organisms no one else on Earth had ever seen: mobile microbes he called "animalcules." He even discovered bacteria by examining "the white, batter-thick plaque lodged between his teeth."

Scientists began asking him to study semen. Biologists had a vague understanding of baby-making, but the inner workings were a riddle, wrapped in mysterious fluids, inside a person. Van Leeuwenhoek could handle oral scum, but he wasn't ready for man jelly. However, as Smithsonian Magazine described, "in 1677 he gave in," becoming the first person to describe sperm cells. It took years of coaxing.

A 1677 letter to the Royal Society in London revealed that van Leeuwenhoek made a withdrawal from his private sperm bank several years earlier because the society's secretary wanted a scientific account. After seeing his little sailors at 270 times their normal size, van Leeuwenhoek "did not continue [his] observations" because he felt icky (and probably sticky). Obviously, he later buckled under peer pressure, but he would only look at the "residue" from doing his wife ... and the sperm of a guy with gonorrhea. It was undoubtedly an organismic experience.

Part and Paracelsus of medical history

Paracelsus was a man of many monikers. Toxicology Sciences referred to him as the "Luther of Medicine," "the godfather of chemotherapy," "the founder of modern toxicology," and Philippus Theophrastus Aureolus Bombastus von Hohenheim (his actual name). Born in 1493, the Swiss physician was pretty forward-thinking for his time. For example, as a university student, he burned medical textbooks he disagreed with. Wait, bad example. He also sought to merge the worlds of chemistry and medicine, and championed the scientific method.

Oddly, Paracelsus claimed you could grow a little man, or homunculus, by incubating human sperm in a horse's womb. After all, he was born in 1493. He even dabbled in alchemy, which surprisingly made him a better doctor. According to the Science Museum of London's Brought to Life project, alchemy convinced him that "metals were the key elements which made up the universe." Paracelsus posited that human bodies consisted of "chemical systems" that could be chemically altered. As a result, he originated mercury treatments for syphilis.

Alchemy also shaped his perception of resuscitation. As Hugh Crone described in the book Paracelsus, the Swiss syphilis-fighter didn't see death as permanent. In fact, he believed you could reconstitute birds that had burned to ash. He also thought lions "were all born dead" and that their parents basically roared life into them. Perhaps Paracelsus approximated that roar in 1530 when he attached a breathing tube to a pair of fire bellows, creating the first known mechanical ventilator.

Benjamin frankly, my dear, I don't give a sham

Exorcisms have a hideous history steeped in misapprehensions about mental illness. Their one saving grace is that they also placed Benjamin Franklin on a collision course with a physician who proclaimed himself a magnet. That epic brain-wreck demonstrated the placebo effect and effectively birthed hypnotism.

The highway to hypnosis was paved by an Austrian doctor named Anton Mesmer, per the Lancet. During the late 1700s, Mesmer studied an exorcist and concluded possessed people didn't need Jesus. According to Psych Central, he cast their "demons" as imbalances of a previously unknown substance he termed "animal magnetism." Mesmer then invented a regimen called "mesmerizing," wherein he waved magnets over people and talked them in to feeling better.

Mesmer eventually realized the magnets made no difference and assumed the magnetism was inside him all along. So he waved his hands over patients who shook and shrieked and probably appreciated the massages Mesmer sometimes gave them. He also claimed he could mesmerize objects, infusing them with healing powers. The Austrian medical community rightly laughed at Mesmer, so he rode his horsepucky to France. France's king also smelled bull and created a commission led by Benjamin Franklin to flush it out. Drawing from well-known exorcism experiments, the team devised history's first placebo-controlled medical study and proved Mesmer's only power was suggestion. However, mesmerizing became the basis for hypnosis and psychotherapy.

The Father, the Son, and the holy split

The Bible credited Christ with myriad miracles, like turning water into wine and walking on water –- or as Christ hopefully called it, grape-stomping. But the holy book never expressly equated him with God. Nevertheless, modern Christians maintain the Messiah is God and God's son. They don't mean it in some technical sense like the song, "I'm My Own Grandpa." They mean God begat himself in the form of Jesus, who always existed but also had a human incarnation that lived, died, and un-died.

While Christians largely buy that notion nowadays, during the fourth century an Egyptian priest named Arius wasn't sold on it. A New Testament professor at Yale Divinity School told PBS that Arius suggested Jesus wasn't "God in the fullest sense." Alexandria's bishop, Anthanasius, vehemently disagreed. As Richard Rubenstein observed in When Jesus Became God, divided Christians devolved into lynch mobs. Riots and rhetoric abounded. Anthanasius "had his opponents excommunicated and anathematized, beaten and intimidated, kidnapped, imprisoned, and exiled." Arius' supporters branded Anthanasius a thief, extortionist, heretic, and murderer. Arian priests even paid a prostitute to seduce an opposing bishop. (The prostitute refused.)

Emperor Constantine sought to settle matters in 325 via the council of Nicaea, during which a bunch of bishops sided with Anthanasius. However, the rift persisted for years as clerics accused each other of everything from licentiousness to disrespecting the emperor's mom. By 381 Anthanasius' side had won. Soon, his adherents called the Holy Ghost God, too.

Newton's theology of gravity

After surviving vicious violence and allegations of mom insults, Anthanasius and his followers prevailed and Christianity adopted the doctrine of the Holy Trinity in the late fourth century. According to orthodoxy, that made Arius anathema. According to Isaac Newton, that sucked. As the Isaac Newton Institute explained, the alchemy-loving math whiz who magically spelled out calculus and set modern physics in motion during the 1600s was a heretic like Arius. (In other words, Newton counted as both a mathematician and an anathema-thematician.)

Newton's British super-brain believed belief in the Holy Trinity was biblically unjustified, per the Newton Project. So it must have irked him to work at Trinity College as a professor. Ironically, while employed there he delved into the arguments underlying the Council of Nicaea and concluded Arius had the right idea. He didn't consider Jesus a deity. In fact, Newton insisted "God was utterly unlike humanity." Interestingly, these ideas informed his ideas on time and space, which he deemed independent from physical bodies because time and space directly related to God's omnipresence.

Newton would reject Descartes' attempt to ground gravity in godless physical processes and offer a God-driven alternative. He articulated his vision of divinity in the second edition of Principia Mathematica, which outlined his notions of motion and gravity. Notably, Newton wrote that God is "void of all body and bodily figure" and shouldn't "be worshipped under the representation of any corporeal thing." Evidently his phenomenal physics was divinely (yet also heretically) inspired.

A dino-sore subject for paleontology

Fans of the 1980s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles cartoon might recall the character Krang, a talking brain in a robotic body that tirelessly strived to subjugate Earth. Maniacal villainy aside, he's the perfect scientist: a ball of intense intellect and boundless ambition. Unfortunately, if you put boundless ambition in a real scientist's brain, you might get something closer to Krang than perfection. Othniel Marsh and Edward Cope, for instance, advanced paleontology and Darwinism in incredibly petty fashion.

As Yale Daily News detailed, Marsh ventured off to the Wild West in the 1860s in search of dinosaur fossils and by 1866 he had become one of the two paleontology professors on the planet. But those accolades didn't sate his hunger for dominance. He eventually stole fossils from fellow paleontologist Edward Cope and humiliated him for making a glaring error in an 1870 publication. That sparked a 20-year game of one-upmanship.

Per UC Berkley, the rivals defamed each other, engaged in espionage, and even dynamited dig sites to spite one another. They furiously snatched up fossils and hastily published sloppy, error-ridden papers about them. Their over-the-top unprofessionalism prompted the U.S. Congress to cut paleontology funding in 1892. On the bright side, Marsh and Cope expanded North America's dinosaur fossil record from 18 known species to well over 130. Marsh's fossils helped Charles Darwin (above) validate his theory of evolution. Marsh even proffered the now-accepted theory that birds evolved from dinosaurs. All it took was embarrassing the scientific community.

A fistula full of scholars

MedlinePlus defines a fistula as "an abnormal connection between two parts inside of the body," such as your windpipe and your food tube or your pooping parts and your lady parts. In short, it ruins human happiness. In fairness, a fistula also redefined how doctors make diagnoses and revolutionized physiology. It didn't act alone, though. The fistula had help from a shotgun, an inquisitive doctor, and an unfortunate fur trapper.

No, the doctor didn't shoot the fur trapper. The shotgun did. As Live Science elaborated, in 1822 Alexis St. Martin (above) of Michigan was accidentally blasted in the belly by another trapper. St. Martin reportedly "had lung hanging out of his wound," which must have been a breathtaking sight. Thankfully, army doctor James Beaumont saw a solution. He embarked on a series of surgeries without painkillers or germ-killers. Understandably, St. Martin got sick of them. This left an abdominal fistula that exposed his innards to the outer world.

Beaumont would spend years looking through the hole to see how St. Martin's stomach operated. He dipped food in the trapper's digestive juices and sent fluid samples to chemists. Back then, doctors didn't comprehend digestion, and most of their medical wisdom came from an ancient physician named Galen who thought brains were made of sperm. Beaumont showed physiologists and physicians the importance of making observations before making anatomical and medical claims. He also observed a connection between emotions and gastric behavior that influenced Ivan Pavlov's famous dog studies.

Killer welfare queen

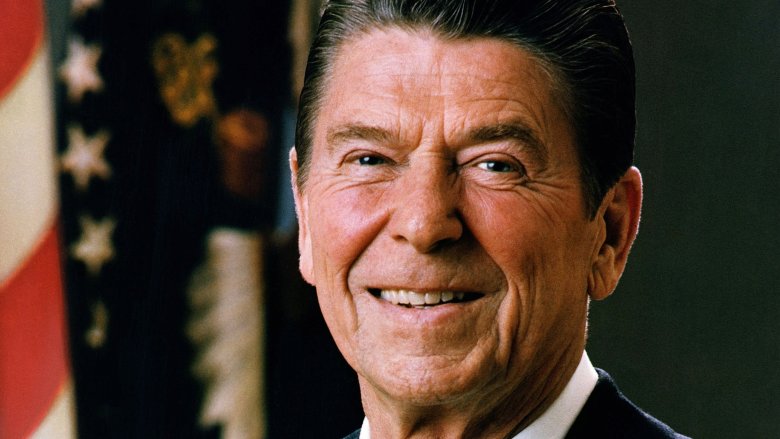

Conservative icon Ronald Reagan's financial policies can be traced to iconic economist Adam Smith. The ties are obvious –- especially the Adam Smith neckties Reagan's White House aides wore. Plus, Reagan loved the free market more than most parents love their children. Yet when Reagan ran for president in 1976, his speeches didn't recap laissez-faire capitalism. Rather, he capitalized on a larcenous criminal.

Slate reported that Reagan railed against an unnamed woman who "used 80 names, 30 addresses, 15 telephone numbers to collect food stamps, Social Security, veterans' benefits for four nonexistent deceased veteran husbands, as well as welfare." Dubbed "the Welfare Queen," she embodied the insidious freeloading often attributed to people on public assistance. Critics later claimed Reagan invented the Welfare Queen to smear poor minorities. However, she was real. Her real name was Linda Taylor.

Taylor milked the government like a Dairy Queen and used her loot to buy fancy cars and visit Hawaii. She could allegedly alter her face to mimic any age or race she wished. Evidence also suggests she posed as a nurse to kidnap babies. Taylor may have even murdered someone. Furthermore, she supposedly practiced voodoo, which is spooky. Authorities only proved welfare fraud, though. Speaking of which, how common is welfare abuse? According to Time, during the 1970s rates reached 55 percent in some cities, but in 2017 the overall rate was 1.5 percent. It turns out the answer depends on when and where you look.

Contact high by Carl Sagan

America's opinion of pot has changed like a dollar at the laundry mat. During the 1830s people perceived marijuana as medicine, per History. As the drug became connected with incoming Mexican immigrants in the 1900s, police and politicians portrayed pot as a wicked weed and states began banning it. In 1936 the film Reefer Madness claimed marijuana turned well-behaved teens into ax murderers. The next year Uncle Sam outlawed it altogether.

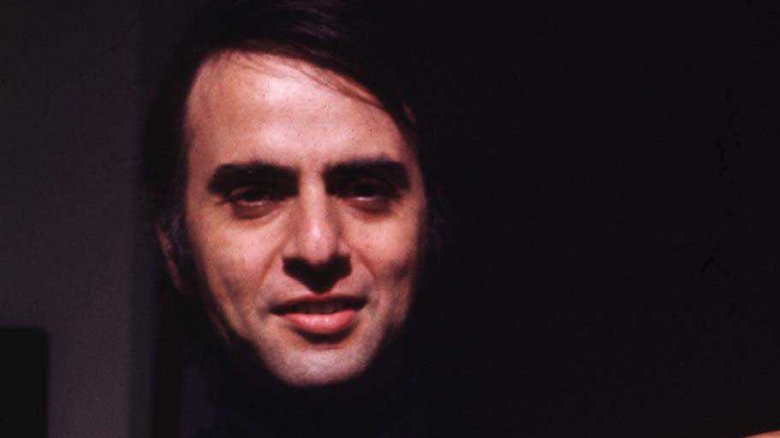

In 1971 Lester Grinspoon's book Marijuana Reconsidered gutted the hogwash authorities peddled about pot. Thus began a 40-plus-year crusade to clear cannabis' name, The Harvard Crimson explained. Grinspoon went on to author influential research touting toking as medically beneficial. And it might never have happened if Carl Sagan (above) hadn't been a pothead. Grinspoon revealed to Vice that he and Sagan knew each other during the 1960s. Shockingly, the mellow astronomer who brought you Contact and The Cosmos got in contact with the cosmos by puffing magic dragon grass.

At the time Grinspoon was still enveloped in a haze of marijuana myths and found Sagan's smoking alarming. He urged the astronomer to quit, to which Sagan replied, "Oh Lester, have a puff, it's not going to hurt you a bit and you'll love it." Determined to disprove Sagan, Grinspoon buried himself in pot research and ended up changing his own mind. He reacted by writing Marijuana Reconsidered, which included an anonymous but astronomically eloquent endorsement of pot from Mr. Cosmos himself.

Make love and Black Hole War

Stereotypically speaking, hippies serve as a reminder that bad hygiene smells bad. In that respect, they don't provide free love, but tough love. However, hippies offer more than the scent of soap-free promiscuity. According to How the Hippies Saved Physics, hippies saved physics. As Nature elaborated, the book linked the creation of quantum information theory to the work of misfit physicists who often operated independently from universities during the 1970s and '80s. Some struggled to land academic employment -– just like jobless hippies –- and found support in strange places.

The list of bizarre backers included New Age gurus. One of them, Michael Murphy, "sponsored workshops at which physicists alternated their hot-tub discussions of quantum mechanics with massages and, in some cases, LSD trips." Perhaps the most impactful was Werner Erhard, who, according to Time, started the first modern self-help "empire" with the advent of "legendarily uncomfortable" EST courses. Erhard based EST on scientology, which is indeed uncomfortable. However, he really dug physics, which is groovy.

Erhard assembled pioneering physicists like Richard Feynman, Stephen Hawking, and Leonard Susskind so they could debate beliefs in his attic. Susskind's book The Black Hole War discussed how one of those gatherings ignited a two-decade disagreement between him and Hawking regarding whether black holes retain information. (They do.) Susskind, who won the war, told the LA Times his spat with Hawking spawned the holographic principle, which essentially suggests "the universe is like a hologram." Far out, man.