Bizarre Things People Used To Believe About Medicine

No one really likes going to the doctor. You have to wait in waiting room for what seems like ages, endure some uncomfortable situations, handle the constant fear of getting some bad news, and deal with conniving health insurance companies. Luckily, we live in an age where most of us can visit doctors who, more or less, know what they're doing — meaning they're not going to suggest we drink radioactive water, prescribe us poisonous mercury, or give our baby morphine for a toothache. Indeed, medicine hasn't always been what it is today, and people used to believe some pretty bizarre stuff about how to "do no harm."

Bathing bred illness

Unless you want to befriend flies or have embraced olfactory sadomasochism, you likely bathe, shower, or at least dunk yourself in a water-filled washing machine every now and then. But long before the days when cleanliness seemed close to godliness, it was considered sinister. As the University of Virginia explained, between the fifth and sixth centuries A.D. and the 1800s, people seldom bathed. Ironically, part of that abstention stemmed from the then-Christian conviction that cleanliness implied "moral laxity." Moreover, doctors deemed dirtiness a shield against sickness.

See, for several stinky centuries, people subscribed to miasma theory, which maintained that bad air bred various illnesses. Since bathing opens up pores, physicians feared it also made the body more permeable to pernicious air. Hence, doctors deduced that staying dirty all day kept the dirt naps away. Rich people began ignoring the doctor's orders during the 19th century, however. Not over health concerns but to stand out from the literally unwashed masses of society. (They likely also enjoyed not looking like the underside of a mud-caked shoe).

With the rise of germ theory during the 1870s and 1880s, medical experts began to see (and smell) the practical benefits of baths. Soon cleanliness ceased being a class issue and was touted as a way to "break the chain" of such infections as tuberculosis. As a bonus, it also eliminated bad (smelling) air.

Babies couldn't feel pain

Babies rule. Something about their comically oversized heads, their always surprised eyes, and their helpless ineptitude just makes people want to hug them forever and protect those adorable bobbleheads from harm. So it might come as a surprise that for the longest time surgeons used to cut infants open without trying to numb their pain. To clarify, babies don't bring out a doctor's inner rage demon. Rather, experts believed that babies couldn't feel pain.

According to The New York Times, this misconception arose during the 1940s as a result of some unfortunate experimental findings. Apparently when you poke babies with pins (please don't), they don't howl like rabid monkeys. This relatively stoic reaction to stabbing led doctors to conclude that newborns just don't register pain. This makes no sense evolutionarily. (Why would humans be least receptive to pain during their most vulnerable stage of existence?) But experts reasoned that since babies weren't fully developed people, their nervous systems were likely also incomplete.

Because doctors didn't want to needlessly imperil babies with pain medications during operations, they simply didn't. As a result, "77 percent of all the newborns who underwent surgery throughout the world between 1954 and 1983 to repair a serious blood vessel defect ... received only muscle relaxants or relaxants plus intermittent nitrous oxide," aka laughing gas. The babies weren't amused. Eventually physicians noticed that babies don't like getting carved like kid-shaped pumpkins and decided it wouldn't hurt to prevent them from hurting.

Masturbation caused two-thirds of all human diseases

Self-sex has come a long way over the years. Nowadays most people think it's normal to lustily tickle your taco or jostle your jerky as long as you do it privately. There are still people who might judge you, but they're usually nuns and your grandmother. Way back in the day, however, whether you pleasured your body was also the business of busybody doctors. Unlike modern medical experts, these extra-old-fashioned physicians blamed everything from fatigue to insanity to blindness on onanism.

According to anthropologist Dr. Michael Patton, these bogus beliefs originated with an 18th-century neurologist named Samuel Tissot. A devout Swiss Catholic, Tissot advised the Vatican on health matters and in 1758 he published the infamously influential Onania, which "scientifically" bad-mouthed masturbation. In 1760, he hammered the point home with On the Diseases Caused by Masturbation. Per an editor's introduction to the work, Tissot based his claims on "stories from his own patients and from the patients of other renowned European doctors."

It's unclear whether the patients merely misapprehended their own symptoms or Tissot took liberties with their testimony, but boys who derived joy from their fleshy sin sticks allegedly grew "pale, stupid, effeminate, idle, weak, and even void of understanding." Patients even reported paralysis. An estimated 800 books subsequently parroted these claims, according to Dr. Patton, who noted: "At one point two-thirds of all medical diseases, medical and mental, were attributed to masturbation." Obviously, people were just doing it wrong.

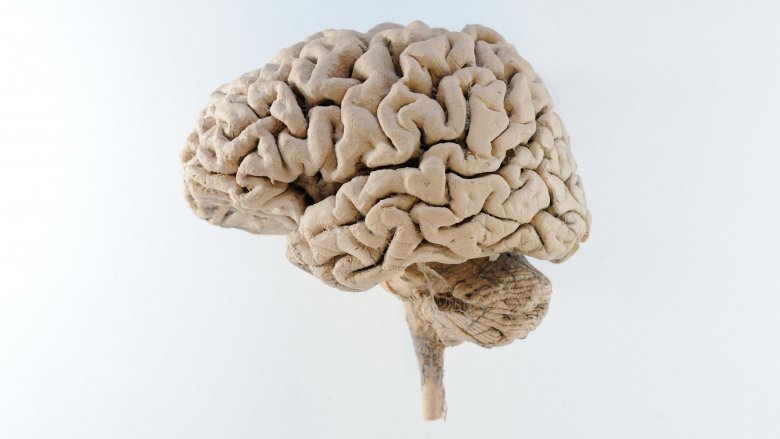

Human brains were made of sperm

For the bulk of human history, the organ people use for knowing things has remained largely unknowable, leading to some fairly fun misunderstandings. For instance, per Live Science, 90 percent of our skull meat consists of sticky stuff called glia (or "glue" in Greek), which most experts wrongly assumed just kept the brain physically intact. As it turned out, those "glue" cells also serve as a live-in janitor that "(mops) up excess neurotransmitters" and performs other vital functions.

The glial glue theory seems wacky in retrospect (why would the brain be nine-tenths adhesive?), but it's got nothing on what people previously posited about that sticky stuff. According to Stanford University, in the second century A.D. the Roman physician Galen theorized that "the brain was a cold, moist organ formed of sperm." (Just imagine how embarrassed he felt whenever he blew his nose.) Surprisingly, Galen wasn't a mischievous middle schooler posing as a quacksalver. He was an esteemed thinker whose ideas persisted well into the Middle Ages.

Naturally, Galen's oddball conceptions about brain sperm spawned some pretty peculiar notions about reproduction. As Stanford University detailed, medieval medical experts believed that during the act of baby-making, the sperm produced in a man's head traveled down to his ... other head. Moreover, they postulated that ladies produced their own sperm, which got classified as a kind of "milk." That raises a ton of uncomfortable questions about ancient and medieval sex education that should probably never be answered.

Guinness was good for pregnant women

Nobody needs an excuse to drink, but it helps to have one. Maybe you're allergic to sobriety or have an ongoing feud with your brain cells. Those are perfectly reasonable reasons. However, things get problematic when booze is treated like a health drink. Then people tend to down it like liquid crack. Unfortunately, Ireland fell into that trap during the 1920s, thanks to a seemingly salubrious brew called Guinness.

To clarify, Guinness does actually have some health benefits. As CNN noted, the stout has plenty of folate, vitamin B, antioxidants, and a fair bit of fiber to boot. But advertisements from the late 1920s made it sound like the best thing since fermented sliced bread. According to the book Inventing Millions, drinking Guinness purportedly saved a soldier's life after the Battle of Waterloo. Its supposedly high iron content later made it a go-to treatment for people recovering from surgery. Physicians placed so much faith in Guinness that they even gave it to pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers.

And here the story takes a depressingly dark turn. Today people know that babies and booze don't mix. But it took some pretty awful birth defects for medical professionals to catch on. This wasn't just a problem in Ireland, either. According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institutes of Health, people throughout Canada, the U.S., and multiple countries in Europe didn't discern how alcohol affected fetuses until "well into the 1970s."

Smoking could soothe your sore throat

Woodland creatures might not seem that bright, but at least they know not to inhale smoke. Humans, by contrast, start tiny fires in front of their faces so they can breathe in lung poison. Granted, most modern-day smokers recognize the risks but singe their airways anyway. But during the 1930s and '40s, Americans got respiratory amnesia and crammed themselves with burnt plant debris without understanding the consequences.

Some of the biggest offenders were physicians. Per The LA Times, 60 percent of doctors smoked during the late 1940s. Maybe cigarettes tasted like hot cakes back then, or World War II and the Great Depression left everyone jaded. But the National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health provided a different explanation. Doctors doubted existing data about the dangers of smoking. (Either that or three-fifths of physicians were just educated junkies justifying their addictions.)

Of course, not every physician failed to see a problem. Some even suspected that cigarettes caused lung cancer. To keep people misinformed, tobacco companies began plying doctors with cigarette samples and inviting them to conventions. And since no human can resist free stuff, many doctors began endorsing cigarettes in advertisements and in their offices. Physicians even falsely informed patients that smoking could soothe sore throats, according to Stanford University. Big Tobacco proved so persuasive that until 1985, the American Medical Association headquarters in Chicago had cigarette machines. The AMA prefers to ignore that part of its past, however, because it's super embarrassing.

Arteries contained air

What's in a name? Lots of things: letters, sometimes numbers, symbols depending on the language, and even Shakespearean tragedies. Perhaps most importantly, names can tell you how a thing is perceived. For example, the term "penis" comes from the Latin word for "tail," which suggests that people used to think they had abdominal butts. In a similar vein, the word "artery" indicates that old-timey medical practitioners had no clue how the circulatory system works.

According to 1828's A Dictionary of Medicine, Designed for Popular Use, "artery" technically means "air-holder." That's not because blood is oxygenated, but because physicians of antiquity often interacted with empty arteries. They didn't have fancy doohickeys that could peer into living, breathing, bodies, so they got their anatomy lessons from cadavers. Since dead arteries don't pump blood, the filling all drains into veins and heart chambers. Physicians not only associated arteries with air, but also the heart. As Stanford University elaborated, the second-century Roman practitioner Galen posited that the heart was a respiratory organ that emitted "vital power or innate heat." That's not a bad guess. It almost makes up for that whole brain sperm thing.

Radioactive drinks increased vigor

These days, people are wary of carrying around smartphones in their pockets, and run for cover when microwaving their Hot Pockets. It's hard to believe that, in the early 20th-century, some poor saps actually thought guzzling down radioactive drinks was healthy!

And why not? Electricity was still a new and life-changing discovery, and posed no real threat to the human body. Hot springs were, and still are, huge tourist attractions, and some natural springs were found to contain radiation. Thus, if you put two and two together, radiation must be good for you! Right? Well, no. But researchers at the time made that correlation anyway, according to a 2004 Popular Science article.

Early capitalists got in on the action, selling everything from rheumatism-curing radon pendants to radioactive suppositories. And, of course, all-natural radon water — such as RadiThor — became the Red Bull of the 1900s, promising to provide numerous health benefits and increased vigor. Unsurprisingly, RadiThor failed to "give you wings," but succeeded at dissolving your bones. Who would've thought radiation would have such brutal consequences? After all, it had been proven to increase the sex drive of water newts!

Heroin could cure the common cold

Up until the 1950s, heroin — the highly-addictive, Schedule I controlled substance responsible for ruining lives the world over — was a regularly-prescribed remedy for the common cold, cough, or bout of diarrhea.

Heroin was first synthesized by an English chemist in 1874, but didn't really emerge on the medical scene until German pharmaceutical giant Bayer got hold of it in 1898, and likely renamed it after the German word "heroisch." Clinical trials proved heroin to be upwards of eight times stronger than its cousin morphine, and was thus prescribed as a potent cure for all sorts of common ailments. Naturally, once patients got a taste for the stuff, they'd want more of the miracle medicine for any minor aches or pains, and — providing you were well-to-do enough to support the habit — doctor's were more than happy to oblige. Though addiction wasn't really a top priority in those days, Bayer's newest "wonder drug" saw increasing demand once people realized you could really put yourself into a euphoric state by injecting it straight into your bloodstream — leading into the decades of serious heroin epidemics we've experienced ever since.

Maybe when it comes to curing a cold, just stick with some soup.

Tobacco smoke up the rectum could revive drowned victims

Nobody likes it when someone is "blowing smoke up your ass," which — if you're unaware — means someone's lying to you, or offering some phony flattery. It should go without saying, however, that nobody would like to literally have smoke blown up their ass, either — though, not so long ago, that was a valid medical treatment.

Have a cold? Try a tobacco smoke enema. Have cholera? Try a tobacco smoke enema. Have anything in between? Try a... well, you get the picture, even if it's probably something you'd rather not picture. The practice of pumping smoke into the rectum was first used by American First Nations people, though it was adopted by English doctors looking to resuscitate drowned patients. A pipe-smoking medic would first try to breathe some life back into a drowned individual by inserting an enema tube and exhaling tobacco smoke straight into the bum, as that was believed to both warm the body and stimulate respiration. After its initial adoption, tobacco smoke enemas became a sort-of medical fashion in Europe, being used to treat headaches, breathing difficulties, the common cold, hernias, and abdominal cramps. Meanwhile, the practice actually posed a significant risk to the individual administering the treatment, as accidentally inhaling meant taking in some nasty stuff from you-know-where. The incorporation of a bellows made this procedure safer... at least for the doctor.

Keep that all in mind the next time you head in for your yearly prostate check.

Mercury was a safe way to treat syphilis

Mercury is a big no-no these days, as science has proven the element to be quite poisonous. If you ask your grandmother, however, you'll learn that wasn't always the case.

Mercury used to be found in children's chemistry sets and toys, but is now kept as far away from kids as possible. Far from just being something fun to play with, the element known as quicksilver was used in medicine regularly. It was commonly prescribed to treat syphilis, typhoid fever, and parasites, though frequently poisoned the patient — though the symptoms of mercury poisoning were often attributed to the previously-diagnosed disease worsening.

Eventually, people started to wise up to the dangers of mercury-use for medicinal purposes. But dental professionals stuck to their guns and defended the poisonous metal to the death. The American Medical Association and the American Dental Association were both particularly fond of the silver stuff, as it was used in both calomel and amalgam — with the latter being the western world's primary source of mercury exposure. If you're reading this, you've no need to fear, however — mercury hasn't been used in dental practices for quite some time, and the advent of penicillin and chlorothiazide all but put medicinal mercury in its grave.

Bloodletting was all the rage

If you step way back in time, to the days of Egyptian pharaohs or Greek gods, there's a good chance your doctor was bleeding you dry. The ancient practice of bloodletting — opening up a vein with a sharp piece of wood, or better — was used to cure virtually every common ailment you could think of. Have a headache? Bleed it out. Running a fever? Drain that overheated blood. Bloodletting was as common as getting a haircut, as proven by the fact that today's striped barber poles are merely evolved symbols of the bloody towels that hung outside the shops of "barber-surgeons."

Bloodletting became less gruesome in the first half of the 1800s, when leeches became the tool of choice for extracting bad blood. In early-to-mid nineteenth-century France, upwards of 35 million medicinal leeches were used on a yearly basis, with 5 to 6 million used annually in Paris, alone. Bloodletting was so trusted, in fact, that even the most powerful individuals were treated by the practice. Charles II was medicinally bled after suffering a seizure, and none other than George Washington was drained of nearly 40 percent of his blood while suffering from a fever and difficulty breathing. Washington died the next day, with many blaming the fact that, y'know, nearly half of his blood was extracted from his body. Such a massive loss of blood probably caused the first President to go into shock.

We'll stick to Tylenol for our headaches, thank you very much.

Cocaine used to be a go-to remedy

Though the likes of Pope Leo XIII and Queen Victoria may have dabbled with the drug, the use of cocaine for medicinal purposes dates back to times way earlier than the 19th Century. Ancient Incas were chewing coca leaves all the way back in 3000 B.C., which helped stimulate their breathing and counter the effects of living with less oxygen. In 1859, medicinal cocaine was first formally extracted from coca leaves. But it really wasn't until Austrian psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud came along — himself a user and fan of the wonder drug — that it became widely known in the world of modern-medicine.

Freud recommended cocaine as a treatment for depression and sexual impotence, but by the turn of the century, it was in a wide-variety of common medicines used for curing toothaches and other common ailments. Coca leaves were also an ingredient in Coca-Cola, promoting the stimulating properties of the drug to the mainstream public. Obviously, cocaine is no longer present in the popular soft drink — but if it was, ordering a large Coke at the movies would probably make even Suicide Squad make sense.

Shark cartilage could cure cancer

One of the more recent bizarre beliefs about medicine claimed that shark cartilage was capable of curing cancer. Surprise! It doesn't.

The smooth and elastic tissue from the toothy sea predator was thought to be a possible cancer cure cancer, since sharks apparently don't get the often-fatal condition — at least, according to Dr. William Lane, who published the best-selling book Sharks Don't Get Cancer: How Shark Cartilage Could Save Your Life, in 1992. Lane appeared on 60 Minutes, which documented a clinical trial with Cuban doctors and patients in Mexico, which he claimed all but proved shark cartilage cured cancer. That led to his second book, appropriately titled Sharks Still Don't Get Cancer. Okay.

Unfortunately for Lane, and any suckers who bought into his books, sharks do, in fact, get cancer — nullifying both books' claims before you even open the front cover. Nonetheless, the damage has already been done, and some people today still believe shark cartilage cures cancer. Clever Dr. Lane even created and sold his own brand of shark cartilage, from his own company, LaneLabs — which has since been barred from making deceptive health claims. Go figure!

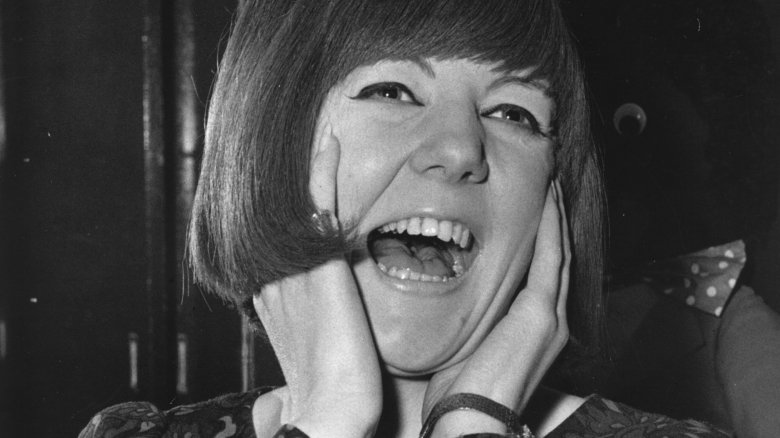

Female hysteria was a thing

Sexism still exists in today's medical world, in one form or another. But it pales in comparison to the cocaine-prescribing days of yore, when medicine was so sexist that women had their very own mental disease.

Known as "female hysteria," the women's-only medical condition was all encompassing. According to Rachel Maine's The Technology of the Orgasm, hysteria was thought to cause...everything. Fainting, anxiety, sleeplessness, irritability, nervousness, "a tendency to cause trouble for others," erotic fantasizing, and even "excessive vaginal lubrication" — hysteria was always the culprit. The term "hysteria" actually derives from the Greek hysterika, meaning uterus, and was first used to describe women who weren't having enough sex — but eventually changed into a go-to medical diagnosis for women with basically any ailment. If a doctor couldn't figure out a problem, it must be hysteria.

So, what's the cure for hysteria, you ask? Manual clitoral stimulation. That's right — masturbation was prescribed in order to combat the symptoms of female hysteria, which ultimately led to the creation of the vibrator in the 1880s. Better than ending up in a 19th-century mental hospital, that's for sure...

Drilling holes in the skull could cure headaches and heartsickness

It's hard to blame human beings for coming up with some dumb medical treatments a thousand years ago. After all, there weren't exactly state-of-the-art anatomical textbooks and well-equipped medical universities in 1000 AD. And yet, no matter how crude your understanding of the human head, drilling holes in the skull still doesn't seem like the best practice.

From 1000 to 1250 AD, Native Peruvians were performing trepanations with hand-drills and other crude instruments. According to discoveries made by UC Santa Barbara bio-archaeologist Danielle Kurin, the practice was meant to treat head injuries, heartsickness, and other possible ailments. Trepanations actually occurred in the region even earlier than that, with the procedure being found in archaeological evidence from the south-central Andean highlands dating back to 200 to 600 AD. If you really want to go back, the first distinct evidence of trepanation occurred some 7000 years ago.

Everyone's fantasized about drilling holes in their skull to relieve migraine. Luckily, we live in an age when we can just pop some pain relievers and sleep it off. Probably better to keep your skull intact.

Drugging your infant with morphine was acceptable parenting

Teething babies sure can be a pain for parents, what with all the crying and commotion. What better way to deal with your fussy child than slipping them a spoonful of "soothing syrup" and watching them drift off into a blissful little nap?

Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup was manufactured in 1845 by the partnership of Jeremiah Curtis and Benjamin A. Perkins, and was marketed as the best cure for infant woes. Curtis officially reported selling more than 1.5 million bottles of the magic elixir, annually, in 1868. Lucky for them, they didn't have to list their ingredients on the labels, because the two main ingredients were morphine and alcohol — guaranteed to make anyone sleep like a baby...including babies!

Largely unaware of what they were feeding their infants, mothers couldn't get enough of the stuff, reporting that "when given to the [child] according to directions, its effect upon him was like magic; he soon went to sleep, and all pain and nervousness disappeared. We have had no trouble with him since." Of course, that's to be expected when he's trippin' on morphine.

"Every mother who regards the health and life of her children should possess [Mrs. Winslow's Soothing Syrup]," one mother confidently claimed. As an added bonus, the stuff was even "sure to regulate the bowels," since constipation is, in fact, a side-effect of using opioids.