Tragic Details About The Cure

The following article includes multiple mentions of suicide and suicidal ideation.

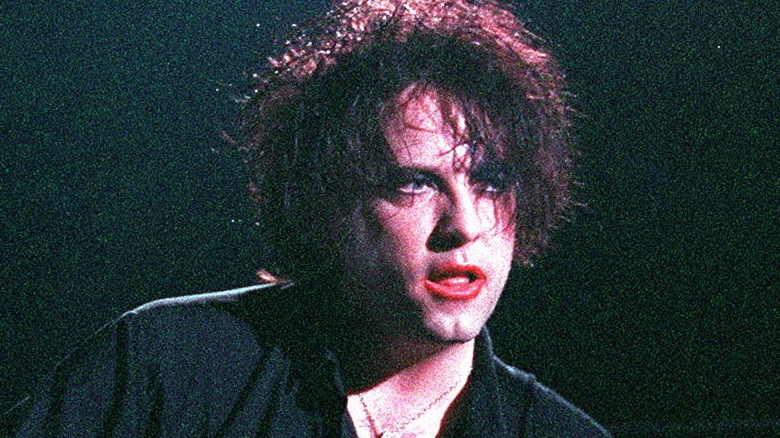

There probably hasn't been, nor ever will be, another rock band that so unabashedly, thoroughly, and accurately explored sadness and sorrow as effectively as The Cure. An active group since the 1970s and with singer and primary songwriter Robert Smith as its leader and only forever member, The Cure defined and popularized alternative rock in the 1980s, bridging punk rock, New Wave, goth, and pop with walls of guitars, keyboards, and audio atmosphere.

There's a palpable air of despair and loss to most every big Cure hit, like "Lovesong," "Boys Don't Cry," "Just Like Heaven," and "Why Can't I Be You?" And so, one might think that the people who make such music might have dealt with some truly traumatic life events. Indeed, Smith and his revolving gang of darkly garmented, wild-haired, moody cohorts write and play that which they know. Many members of the iconic U.K. band have endured a fair amount of real-life strife and tragedy. Here are the very worst things to ever happen to the inner circle of The Cure.

Sadness, depression, and death inspired The Cure

A lot of the music of The Cure can be described as some combination of melancholy, heartbreaking, and sad. Those emotions aren't only a major element of the band's catalog, but are responsible for its very existence. After the spare post-punk of 1979's "Three Imaginary Boys," The Cure fully embraced darkness and gloomy sonic atmosphere on 1980's "Seventeen Seconds." "It was the first record I felt was really The Cure," Smith said in the liner notes of a reissue of the album (via Long Live Vinyl). In 1981, The Cure's mood and musical approach would further darken — Smith's grandmother unexpectedly died, and drummer Lol Tolhurst's mother was diagnosed with cancer (which would ultimately claim her life).

Around this time, Smith dealt with persistent thoughts of meaningless and impending death. "I was 21, but I felt really old ... older than I do now," Smith told Uncut (via Mark Fisher's "K-punk") in 2000. "I had no faith in anything. ... I genuinely felt that I wasn't going to be alive for much longer. I tried particularly hard to make sure I wasn't." Adding to the despair, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: the May 1980 death of a U.K. post-punk contemporary, the frontman of Joy Division. "The whole thing was reinforced by the fact that Ian Curtis had killed himself. I knew that The Cure were considered fake in comparison. ... If I wanted people to accept what we were doing, I was going to have to take the ultimate step."

A man attempted suicide at one of the band's concerts

In July 1986, The Cure was scheduled to play The Forum outside Los Angeles, California, the final concert on the 17-date, U.S. "Beach Party" tour. As the members of the band gathered and stayed close to the crew, who would guide them through the dark, backstage areas to safely get to the stage, and as the crowd's excitement and cheers grew, a 38-year-old concert-goer named Jonathan Moreland jumped up, removed a hunting knife he'd hidden on his person, and stabbed himself. Some fans urged him on, apparently thinking that his actions were a staged bit of theater befitting the gloomy music and imagery of The Cure.

Security and police personnel acted quickly to stop Moreland from killing himself. "I saw the commotion and heard screaming and the crowd clearing as the guy jumped onto his seat," then-crew member Perry Bamonte said in Jeff Apter's "Never Enough: The Story of The Cure." "It was surreal and disturbing." Moreland would finally be subdued by a police-fired stun-gun shot. He later admitted that he was depressed over an unrequited love; it's been reported that he died during a post-concert hospitalization, but contemporary news reports stated he was in good condition the day after the incident.

Two Cure concerts in Argentina ended in riots and death

In March 1987, The Cure visited South America for the first time, kicking off a tour leg with two shows at a stadium in Buenos Aires, Argentina. When the band arrived at the airport, it was mobbed by fans, and a crowd of at least 500 fans waited outside the hotel, according to "Never Enough."

On the first night of the two-night stand, organizers discovered that the concert had more than sold out — about 19,000 tickets had been purchased for a venue that only held 17,000 people. When thousands of fans were turned away at the gates, they were decidedly angry, and their frustration coalesced into a riot. Police cars that arrived on the scene were destroyed by the horde, multiple security dogs died in the fracas, and a hot dog vendor became so distressed that he suffered a fatal heart attack. The Cure took the stage anyway, and the riot raged on inside the stadium. "For almost two hours we play[ed] amidst defeating bedlam, before rushing off, screaming, into the car and away," Robert Smith said. Three people died that night, according to a local newspaper (via Lol Tolhurst's book "Cured: The Tale of Two Imaginary Boys").

On night two, with the temperature reaching 100 degrees Fahrenheit, enhanced security and imposing barricades at the stage couldn't prevent another outbreak of violence. Smith claims to have seen law officers engulfed in flames while the crowd threw objects at the band. After getting struck in the face with a soda bottle, Smith rushed through the rest of the set and got the band out of there.

Alcoholism cost Lol Tolhurst his place in The Cure

From The Cure's early days, drummer-turned-keyboardist Lol Tolhurst exhibited some problems with alcohol. The band was removed from its first high-profile showcase, opening for Billy Idol's band Generation X, after an extremely drunk Tolhurst entered a bathroom and urinated on Idol, who was in the middle of an intimate act with a fan.

During The Cure's 1987 tour of South America, Tolhurst's drinking problem had gotten to the point where he was consistently intoxicated and couldn't play the band's songs very well. That led to the hiring of supplemental keyboardist Roger O'Donnell (formerly of the Psychedelic Furs), according to "Never Enough." Meanwhile, the rest of the band members took out their frustrations and anger on Tolhurst, who was reportedly too drunk to ever fight back or defend himself.

Following an 18-month hiatus at tour's end, and the recording of the album "Disintegration," The Cure fired Tolhurst as a direct result of his addiction issues. "I was most certainly disintegrating. Emotionally and physically it was all falling apart," Tolhurst told Billboard. He was officially dismissed after a drunken incident at a listening party for "Disintegration." "Half is good, but half is s***!" Tolhurst screamed, as recalled in his book "Cured: The Tale of Two Imaginary Boys," and then ran out of the building sobbing. Some time later, Tolhurst received his firing notice from Smith, his childhood friend, in the mail.

The nasty lawsuit between Lol Tolhurst and The Cure

Lol Tolhurst helped Robert Smith form The Cure back in the mid-1970s. More than a decade later, after much success and a lot of alcohol-related unreliability, Smith kicked Tolhurst out of the band. Shortly after his 1989 exit, Tolhurst filed a lawsuit against his former band in the U.K., alleging that he'd been unfairly removed and had been coerced into an agreement entitling him to an egregiously low royalty rate of 2% on Cure recordings. During proceedings, Smith testified to Tolhurst's inability to function in a professional capacity due to his drinking, citing how the keyboardist put colored stickers on his instrument as a tool to help himself remember what notes to play. Tolhurst retorted with examples of pervasive alcohol use throughout the band, including the time the group accumulated $3,000 in booze charges on a European train trip.

The judge ultimately ruled in favor of The Cure, agreeing with the band that Tolhurst's drinking had turned problematic and affected his musicianship. Even worse for the former Cure member: He'd racked up legal bills to the tune of $1 million, and it took him 10 years to fully erase his debt. At the one point, the U.K. government confiscated 75% of his wages, which had declined significantly once he left The Cure.

Lol Tolhurst's daughter died in infancy

Original member of The Cure Lol Tolhurst married his first wife, Lydia, in 1989. Not long after his dismissal and royalties lawsuit with his former band was settled in 1994, Tolhurst and his wife found themselves expecting a baby, but the pregnancy would end in tragedy. "We had lost a child, a daughter, due to complications during her birth," Tolhurst wrote in "Cured: The Tale of Two Imaginary Boys." Tolhurst blames the medical catastrophe on doctors. "Our original doctor who was going to deliver her was not available and a stand-in took over. Unfortunately, he was fresh out of medical school and didn't have that much experience yet." The substitute doctor reportedly mishandled an issue, and the infant experienced a critical loss of oxygen for multiple moments. That was long enough to ensure that the child's lifespan would last no more than two weeks.

After observing their daughter, named Camille India, for that period of time in a hospital's neonatal intensive care ward enduring numerous tests and procedures, the Tolhursts were allowed to take their daughter home, where she died. Lydia Tolhurst became pregnant again and gave birth to a baby boy named Gray, but Lol Tolhurst believes that the loss of a child contributed strongly to their eventual divorce.

A post-Cure bandmate of Michael Dempsey died by suicide

Bassist Michael Dempsey was an original member of The Cure, his time in the band dating back to 1976, when it was a high school trio (with Robert Smith and Lol Tolhurst) called The Easy Cure. Dempsey would depart The Cure after the release of its first album, "Three Imaginary Boys," in 1979, and would join The Associates, a pop-oriented New Romantic group who'd score a string of hits in the U.K. The Associates had previously toured with The Cure and poached Dempsey away. Nevertheless, the acts remained on good terms, with Smith singing backup on the other band's "The Affectionate Punch."

Members of The Cure and The Associates alike were devastated, then, in January 1997 by the death of the latter's lead singer, Billy MacKenzie. The singer-songwriter, during a period of attempting to restart a dormant career, died by suicide. McKenzie was 39 years old.

Reeves Gabrels' friend and associate David Bowie died of cancer

After contributing as a guest to The Cure's 1997 single "Wrong Number" and playing with Robert Smith in the side project COGASM, Reeves Gabrels officially joined the band in 2012. In the decades prior, Gabrels built an illustrious career as an alternative rock guitarist, with David Bowie helping him land gigs with Nick Lowe and Deaf School before hiring him to play in his hard rock outfit Tin Machine. For the entirety of the 1990s, Gabrels was Bowie's main guitarist, both on stage and on record. Gabrels wrote dozens of songs with Bowie, too, before breaking away from the rock legend in the early 2000s to pursue other musical avenues.

In January 2016, Bowie unexpectedly died days after his 69th birthday. The cause of death: cancer, the diagnosis of which hadn't been publicly disclosed. Gabrels participated in the global movement of mourning and tributes for his friend and collaborator. "We shared apartments together. We borrowed socks from each other." Gabrels told NPR. "The picture I have in my head is of him cracking up in the studio. Because we just used to be able to make each other laugh."

The death of another musician profoundly affected Robert Smith

In the 2010s, The Cure frontman Robert Smith landed a position as the curator of the Meltdown Festival, an annual band showcase that featured nearly 100 bands playing in multiple venues in London over a 10-day period. "And I picked them all," Smith explained to the Los Angeles Times in 2019.

One of the acts that Smith had personally selected to play the 2018 Meltdown Festival: Frightened Rabbit, a Scottish indie pop-rock band built around the voice and songs of frontman Scott Hutchison. About a month before Frightened Rabbit was set to take the stage at Smith's behest, Hutchison was reported missing; two days later, the body of the 36-year-old musician was found in a waterway outside Edinburgh, Scotland. Hutchison had a history of depression, and his death was ruled a suicide.

Smith deeply felt the loss. "It's awful," he told Time Out (via Far Out). "I've been listening to them for 10 years. I've never met him, but I feel I know him because of his voice."

Robert Smith suffered three successive losses

The Cure made albums regularly throughout the 1980s and 1990s. As of 2023, the band's last studio album to date was its 13th, "4:13 Dream," released in 2008. In 2019, everyone in The Cure but main songwriter and lead singer Robert Smith had completed their contributions to a record called "Live From the Moon," with Smith conceding to the Los Angeles Times that his negligence in laying down his vocal tracks was "as ever, what's holding up the album."

One other reason the band hasn't released an album since 2008: Smith lost his passion for music, and he was inspired to write again, which helped him cope with tremendous personal tragedy. "I was offered the chance to curate the Meltdown Festival and I said yes," Smith said. "So I threw myself headlong into it and started listening to bands again and meeting kids who were in bands, and something clicked inside my head: I want to do this again. It came as a bit of a shock to me, to be honest."

The album could be one of the bleakest and most forlorn The Cure has ever recorded. "It's very much on the darker side of the spectrum. I lost my mother and my father and my brother recently, and obviously it had an effect on me," Smith said.

'80s-era The Cure drummer Andy Anderson died of cancer

After the recording of the 1982 album "Pornography," The Cure drummer Lol Tolhurst moved over to keyboards, necessitating the addition of new drummer Clifford "Andy" Anderson. His work first appeared on the single "The Lovecats" and the 1984 album "The Top," and he left the Cure shortly thereafter. Anderson also recorded and performed with other major acts before and after his stint in The Cure, including Peter Gabriel, Iggy Pop, and Hawkwind.

In February 2019, Anderson announced in a Facebook post that he'd been diagnosed with an especially virulent form of cancer — it was in Stage 4 and terminal, meaning death was imminent. "Their [sic] is no way of returning back from that, it's totally covering the inside of my body, and I'm totally fine and aware of my situation," he wrote. Nine days later, Anderson's former Cure bandmate, Lol Tolhurst, broke the news of Anderson's death, on Twitter. "I just heard from some friends who were there with Andy as he passed," Tolhurst wrote. "It is a small measure of solace to learn that he went peacefully at his home." Anderson was 68.

A long-time Cure crew member died suddenly

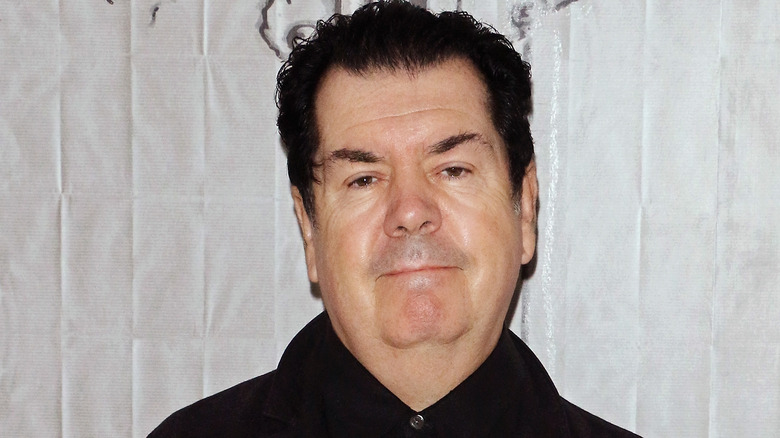

Drummer Jason Cooper began his three-decade-long tenure in The Cure in the mid-1980s. For many of those years, his primary drum technician — the road crew member who sets up Cooper's instrument and makes sure it's in perfect working order — was Paul "Ricky" Welton (pictured). But during the band's 2019 tour, Welton suffered an unexpected and serious cardiac event, and was hospitalized. He died just days later, on August 23, 2019.

The following evening, The Cure played the Rock en Seine festival in France. The band concluded its set with an emotional tribute to Welton, playing "Boys Don't Cry" in the drum tech's honor. For the remainder of the tour's concerts, per Cure guitarist Reeves Gabrels' Twitter, the band and crew left a stool with a beer on it just behind the drum set, as that's where Welton always sat during shows. In June 2022, Cooper took part in the 54-mile London to Brighton Bike Ride, a charity event to raise money for the British Heart Foundation — which the drummer rode in his tech's honor.

If you or anyone you know is struggling or in crisis, or needs help with addiction issues, contact the relevant resources below:

- The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org

- the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).