The Untold Truth Of Harambe

Anyone who was of a functional, conscious age in 2016 will always remember Harambe. He was, of course, the 17-year-old gorilla who was shot and killed when a 3-year-old slipped away from his mother, and ended up in the moat of the Cincinnati Zoo's gorilla exhibit. Harambe had plucked him from the water and spent between 10 and 15 minutes with him, before things escalated to the point where zoo officials said they had no choice but to kill him.

Backlash was swift, with international media reporting on not only the incident, but the online harassment suffered by the mother of the child when she took to social media to thank the zoo for their quick action. (It was also later reported that in spite of petitions demanding otherwise, she would face no charges.)

Harambe became the meme of the year, and it was a weird thing. Outrage over the killing of an endangered animal and demands that the boy's parents be held accountable turned into memes ridiculing the same people who were outraged, and then, the whole thing perhaps predictably veered off into outright racism. The Cincinnati Zoo, meanwhile, continued to support their decision as the right one, sticking by their original statement and adding (via CBS News ): "We are all devastated that this tragic accident resulted in the death of a critically endangered gorilla. This is a huge loss for the zoo family and the gorilla population worldwide." But who, exactly, was Harambe?

He was abandoned and then hand-raised by a keeper

As detailed in a 1951 issue of Life, getting gorillas in zoos initially meant heading out into their native habitats, finding a family that had one or two baby gorillas, and killing the adults that tried to protect those babies before taking them away and transferring them to a life of captivity. The first gorilla wasn't born in captivity until 1956, and it wasn't any less controversial: Babies were often rejected by mothers that didn't know how to care for them.

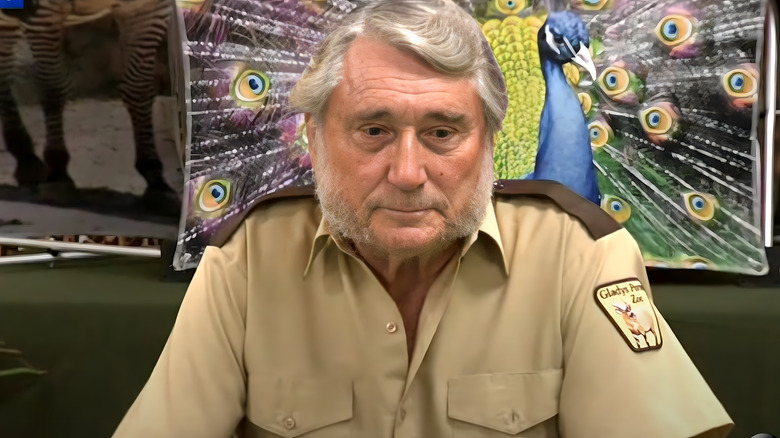

And that didn't change as the decades rolled on. Harambe was born at Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville, Texas, and according to what the zoo's facilities director, Jerry Stones (pictured), told People, he was rejected by his mother when he was 21 days old. "I ended up taking him home that night, and many nights after that. I'd feed him, and change his diapers just like you would a human baby." He added (via ABC News), When I took this baby home, I was totally responsible. You become Mom. They look at you just like a human baby."

Stones said that he interacted with Harambe face-to-face until he was about 7 years old. The reason was pretty straightforward: He was so playful that there was a risk Stones would get hurt. He quickly clarified, "He was never aggressive or mean to people, [but] you stop going in their enclosures because if they play rough and you get hurt, that would be your fault."

Harambe was chosen for the breeding program because of his loving nature

Harambe was moved to the Cincinnati Zoo in 2014, and the transfer was done as part of a program called the Gorilla Species Survival Plan. SSP chair Kristen Lukas describes it as "like a really complex chess game," and since the program has about the same number of males as females, but there's only one male to a group of females, not all the boys get a family. Harambe was on the shortlist.

Jerry Stones of the Brownsville Zoo is arguably the one who knew Harambe the best — changing a baby's diaper and caring for the infant leads to a unique bond. He told Wired, "I was positive he would make an excellent troop leader, so I pushed SSP to do it." Why? Simply put, he was family man material. Stones says that even when he was young, he was incredibly loving and protective. He was part of a group that keepers reintroduced a hand-raised baby to, and it was Harambe and his aunt, Martha, who took the baby under their wing.

Harambe was everything that keepers wanted in a good leader, and Stones told ABC News, "I raised I don't know how many baby gorillas, but he was memorable because he was so intelligent. He showed a positive attitude as far as leadership. He nurtured his siblings. He would carry them around. That was one of the reasons I pushed for him to go to Cincinnati, so that he could have a family."

His mother, brothers, and half-sister died in a horrible way

In 2002, a horrible accident happened at the Gladys Porter Zoo. (Pictured is one of their gorillas.) When first responders arrived on the scene, they found zookeepers and their gorilla charges suffering from the effects of chlorine gas: Someone had accidentally left a container of tablets near a space heater, which melted and — when the tablets got wet — released the gas. Three gorillas died immediately — 10-year-old Kayla and her 11-month-old baby, and 2-year-old Uzuri — and a fourth, Caesar, died after initially being rescued and put on a ventilator.

Other gorillas weren't mentioned by name, but Harambe was there. He was 2 years old at the time, and everyone who died was a member of his family. Kayla was his mother, Uzuri was his half-sister, and both Caesar and the baby Makoko were his brothers.

Harambe's father also died young. Although the average lifespan of a gorilla in captivity is between 35 and 40 years (and it's not unusual for them to live longer than that), Harambe's father, Moja, died at 29. The year before Harambe was moved to Cincinnati, Moja unexpectedly died while in his enclosure. The cause? Heart disease, which is found in an estimated 70% of adult, captive, male gorillas.

His first caretaker has shared stories of his playful nature

When Harambe was killed, Gladys Porter Zoo facilities director Jerry Stones was devastated. He described the gorilla's loss to ABC News, saying, "It's like losing a family member. It tore me up. I was very close to him. His whole life, I was with him."

Harambe may have become the meme of the year in 2016, but no one knew him quite like Stones. When he spoke with Cincinnati.com, he gave some insight into Harambe's character — and he could have been describing any school's class clown. "He was beautiful and a true character — so mischievous and not aggressive. He would throw water on the female keepers before running back and hiding in the back of his exhibit like, 'Haha, I got you!' He would take a keeper's blanket and just run off. Very fun-loving, and so intelligent," Stones recalled.

Stones recalled a toddler-esque Harambe playing catch-me-if-you-can with his keepers, making up his own games, and causing a few skipped hearts in the process. "If he climbed a wall and they didn't rush over, he'd ... clap his hands and fall backwards so they'd catch him." While Stones carefully avoided supporting or condemning the zoo's decision to shoot and kill Harambe, when he spoke to People about his own feelings of loss, he said, "I know it's crazy to think somebody would be that touched by these animals, but they're so, so special."

How much of a gorilla was he? Weirdly, it's debated

Hindsight is 20/20, and everyone had an opinion on whether or not the right decision was made to shoot Harambe, what could have been done differently, and who was in the wrong. That's definitely been true in the debate about Harambe's behavior on that fateful day, with scores of people analyzing footage and often pointing to the 1996 case of Binti Jua (pictured), a female gorilla who carefully picked up a 3-year-old boy who had fallen into her enclosure and carried him to keepers.

But it might actually not be that straightforward. Marc Bekoff is a professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and in a piece for Scientific American, he wrote that getting a handle on the thoughts and lives of animals like the captive-born and captive-raised Harambe is difficult.

He, after all, had none of the experiences that a wild gorilla had, for better or worse: "Being a zoo-ed animal, Harambe lost all of his freedoms ... While some might say Harambe had a "good life" in the zoo, it doesn't come close to the life he would have had as a wild gorilla. Indeed, one might argue that the animal people were seeing was not really a true western lowland gorilla, surely not an ambassador for his species." Bekoff even went as far as to question keeping animals in captivity to learn about them, because we're not learning anything about their true, wild nature when they're raised in a cage.

Did Harambe's death impact captive breeding programs and species numbers?

At the time of Harambe's tragic death, there were around 360 gorillas under the umbrella of the Species Survival Plan. Zoo historian Jeffrey Hyson explained to The Washington Post that it only came about in the 1960s and '70s as a response to "rampant inbreeding in zoo populations, which led to all sorts of birth defects and health problems."

It wasn't ideal, and it didn't go hand-in-hand with other new ideas, like preserving species that were at risk in the wild. Western lowland gorillas like Harambe are included in that, being vulnerable to habitat destruction, Ebola, and poaching, but Hyson said that Harambe's death wasn't actually a massive blow to the species for a pretty heartbreaking reason: There was little chance that any of his offspring would ever be released into the wild.

It's nice to imagine that baby gorillas are at some point released into the wild to be accepted into new family groups, but that doesn't actually happen. Former Wildlife Society director Michael Hutchins describes captive zoo animals as an "insurance policy," held in case the animals go extinct in the wild, and Hyson explains that Harambe's loss wasn't going to impact plans for increasing the numbers of wild gorillas. He went one step further, saying the question of captive breeding was an important one: "I do think there's an important ethical question about, well, bred for what? In the overwhelming majority of cases, it's bred to be another generation in the zoo."

What happened to Harambe's body?

Here's a morbid question: What, exactly, happened to Harambe's body? For starters, zoo officials said that one of the first things that happened was the harvesting of viable sperm samples, which would be preserved and perhaps used in the future. Gorilla Species Survival Plan head Kristen Lukas clarified to Reuters, "Currently, it's not anything we would use for reproduction. It will be banked and just stored for future use or for research studies." (As an interesting footnote that speaks to whether or not zoos breed captive gorillas to release into the wild, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums says that with the then-current population of captive gorillas, females were often put on birth control to stop breeding.)

As for his remains, it's unclear just what happened to him. Vice reached out to Adrienne Zihlman, a professor of physical anthropology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She said that while some zoo animals are cremated, others are turned into skeletons and given to museums, and still others are used for research purposes. She said that there was a whole network of research facilities waiting to try to get corpses for dissection and study, and given Harambe's young age and robust health, he would have been a prime candidate for research. Zihlman even went as far as to say that if he was cremated, "it's a lost opportunity."

What happened to Harambe's ladies?

Harambe wasn't alone in his enclosure, and at the time of his death, he was living with two female gorillas named Chewie and Mara. The hope was that the still-young Harambe would form a family group of his own, so what happened to them? While there was speculation that they would go into a period of mourning, Jerry Stones suggested (via People) that "They'll handle it just fine. I've been around gorillas that have had losses in their troop, and they stay quiet for a few days, but they're okay."

While the zoo never directly addressed how Chewie and Mara were handling the loss of Harambe, they did announce that in September 2017 — a little over a year after Harambe's death — a new gorilla was transferred in to live with the two females he left behind. Mshindi was moved in as a part of the same captive breeding program that Harambe was a part of, but doing a little searching reveals that he didn't stay there. In 2023, three of Cincinnati's gorillas — Mshindi, Tulivu, and Bandia — were transferred to the Detroit Zoo.

The prior year, the Cincinnati Zoo had announced that they were doing some rearranging within their gorilla groups. They stressed that it was completely normal for gorilla females to move between family groups, and said that Mara had been reunited with her mother, while Chewie was moved into another group to fill a much-needed leadership role.

There's no consensus on Harambe's behavior that fatal day

One of the two biggest questions surrounding Harambe's death was why officials didn't choose to use a tranquilizer, which was seemingly refuted by an official statement saying that it would have taken too long, and may have caused an angry Harambe to hurt the boy. When Newcastle University ethology (animal behavior) professor Melissa Bateson said she understood the outrage, telling the Independent, "When I've seen animals shot with tranquilizers, they've gone down very, very fast. One issue is the animal could have become confused, so the zoo was probably worried."

As for Harambe's behavior, former Zoo Atlanta head Terry Maple told National Geographic that at the end of the day, it was impossible to tell if Harambe was playing with the child, or growing increasingly agitated by the crowd. Although he was pretty sure he was just playing with the boy like any gorilla would play with a youngster, he stresses that they still made the right decision: Even harmless play could end in tragedy.

Author and University of New England professor Gisela Kaplan agreed, telling The Daily Telegraph that there were none of the typical displays of aggression seen: "The silverback would've understood that it was a defenseless child," she said. "They would not normally attack, they are not an aggressive species, [and] in the wild, I'm certain the boy wouldn't have been killed." She echoed what countless others have said: The decision was wrong.