How Superman Defeated The Real-Life KKK: A Wild True Story

The Last Son of Krypton, The Man of Steel, The Man of Tomorrow, Kal-El — Superman has gone by many names over the 85 years he's dominated comic books, movies, TV, and even radio. Over thousands of pages and hundreds of storylines, Superman has faced off against one of the most recognizable rogues' galleries in the American canon: Lex Luthor, Darkseid, Doomsday, General Zod ... and The Clan of the Fiery Cross. That last one may not enjoy the same name recognition as the other A-list villains, but it's recognizable for another reason — The Clan of the Fiery Cross was designed as a thinly-veiled fictional stand-in for the unfortunately nonfictional Ku Klux Klan.

In June of 1946, on radios all across America, Superman went head to head with his own "Clan," battling their racist dogma and seeking to save innocent lives. But this radio program was much more than a typical superhero story, and its unorthodox contributors included a real-life secret agent, two down-on-their luck comic strip creators, and one of the most hateful terrorist organizations to ever exist on American soil.

This is the true story of how Superman leapt off the pages of Detective Comics and out of the radio waves to take on the KKK.

The IRL League of Villains

To really understand how this all played out we need to do what many superhero tales have done and begin with the villain's origin story.

It all started in 1865, when six former Confederate officers from Pulaski, Tennessee, got together to form a secret fraternal organization. They named their little club with a combination of two words from two languages: the Ancient Greek word "kuklos" (meaning circle) and the English word "clan." The K must have looked more menacing than the C. The boys from Pulaski met with some early success franchising their secret society. Copycats popped up all across the South, and after congress granted Black men voting rights in 1867, these clubs banded together to form a national organization.

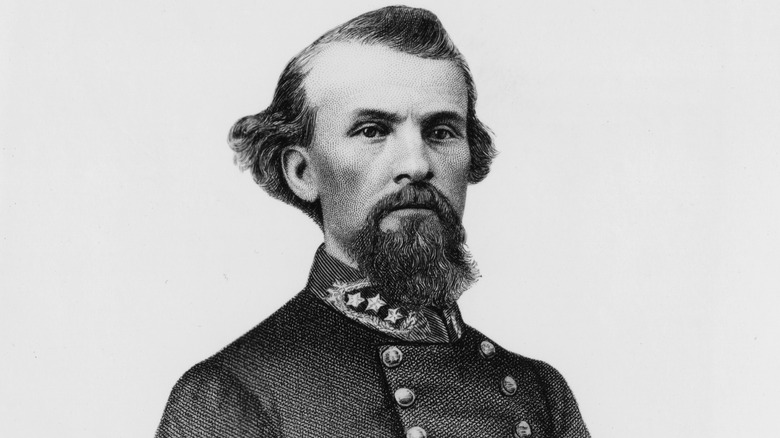

As their first Grand Dragon, the Klan selected Nathan Bedford Forrest — a former Confederate general, slave trader, and paragon of the Southern gentleman. In the ensuing years during and after reconstruction, the Klan stopped at nothing to destroy Black communities and instill fear in those who oppose them. Thousands of Black Americans lost their lives or were driven from their homes.

It became so bad that in 1869, even Forrest said it was too much and ordered the Klan to disband, but at this point Frankenstein's racist monster was already on the loose. Even the Grand Dragon himself couldn't get him back in his cage. The violence continued, and in 1870 and '71 congress passed the Enforcement Acts giving President Ulysses S. Grant the power to suspend habeas corpus and send federal troops to suppress the KKK. Grant exercised this power with his trademark impugnity and brought hundreds of Klansmen to justice.

Grant's second campaign against the South was nearly as devastating as the first one — so much so that by the end of the 1870s the KKK was nearly destroyed. Unfortunately, as it turns out, you can destroy bad people, but bad ideas tend to be shockingly resilient.

The Klan returns with a vengeance

In 1915, inspired by the popularity of D.W. Griffiith's horrifically racist film "Birth of a Nation," a man named William Joseph Simmons decided to relaunch the Klan. He announced its rebirth with an enormous cross burning at Stone Mountain outside of Atlanta. His new Klan grew to a few thousand members over the next several years, but Simmons had an even bigger vision.

To execute, he hired a PR firm. Really.

After conducting a little market research, his PR team found that — in addition to Black people and Jews — their target audience of White Protestant Americans also feared Latinos, Asians, Bolsheviks, Catholics, union workers, women who dress immodestly, people who drink alcohol or listen to jazz, and even the influence of motion pictures. In order to expand their reach, the Klan needed to consider expanding their hate — and expand they did.

After the Klan launched its focus-grouped "100 Percent Americanism" campaign, membership exploded. By the mid-1920s, the KKK had as many as 4 million members, spread across traditional strongholds and new chapters in unexpected locales like Indiana, Pennsylvania, and New York. Though some historians suggest that the Klan of this time was little more than a social club, lynchings, kidnappings, and intimidations were still carried out in the Klan's name. What's worse, with its newfound money and voting power, the Klan wormed its way into state and local politics at all levels. This made prosecuting crimes related to Klan activity extremely challenging.

America needs a hero

Enter: Stetson Kennedy.

Kennedy was a writer and investigative journalist, and boy did he hate the Klan. He grew up in the South and saw the effects of violence and bigotry on Black and other minority communities up close. By the 1940s, Kennedy had grown frustrated with simply writing about hate groups. He wanted to take real action to stop them, so he took it upon himself to infiltrate the KKK at its heart in Atlanta, Georgia.

This covert op gave Kennedy a front row seat to the next attempted revival of the Klan. In late 1945, the head of the Klan in Georgia, Samuel "Doc" Green, proclaimed the return of the Klan with a series of cross burning ceremonies on Stone Mountain, the same location Simmons had used 30 years earlier. With the influx of post-war immigrants — especially Jewish survivors of the Holocaust — and the return of Black soldiers who bled and died for America overseas, Green hoped to once again capitalize on the fears of white Americans and drive up membership numbers.

Kennedy pulls back the white sheet

Working with at least one other informant, Kennedy began to pull back the curtain on the inner workings of the Klan. He made two important discoveries: First, despite its status as a charitable, non-profit organization, the Klan was funneling a large portion of the money from membership fees, robes, and other Klan paraphernalia into the pockets of its leaders. (Is it even a right-wing hate group without a little grift at the top?) He passed this information — along with the names of predominant Klan members — on to law enforcement, The Washington Post, and the Anti-defamation league.

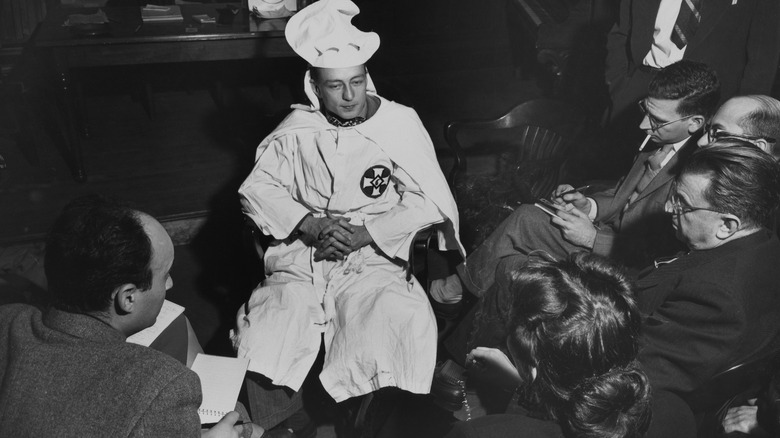

Second, Kennedy revealed the abject silliness of Klan rituals. Yes, the Klansmen interacted with each other through a series of secret signs, counter-signs, and handshakes. The official Klan greeting is a limp left-handed handshake where you slap your hands together and flop them around like a dying fish. All the lame pageantry of the Klan meetings gave Kennedy an idea: What if he could expose the inner workings of the Klan to a wider audience and demonstrate the foolishness of the men involved? What if social pressure could have the same effect on the Klan as legal pressure?

Kennedy reached out to the producers of "The Adventures of Superman" radio program and offered to feed them inside information on the Klan if they agreed to write the KKK into their show as an antagonist for Superman. The producers loved the idea, and starting June 10, 1946, Superman began his battle with "The Clan of the Fiery Cross," seeded with intel from Stetson Kennedy.

Superman battles The Clan of the Fiery Cross

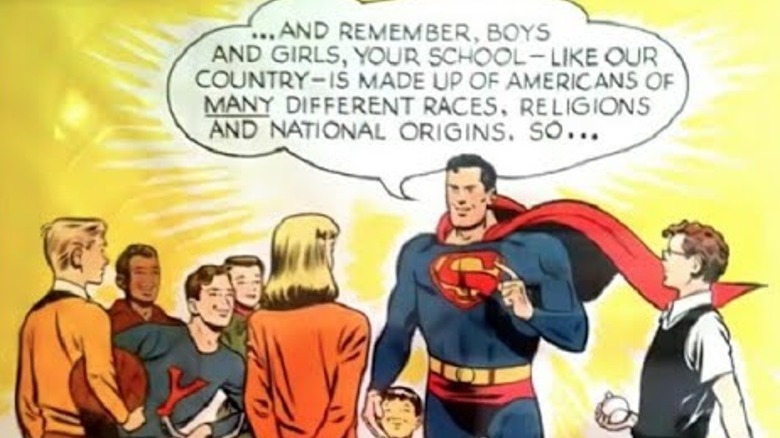

Here's the premise: The Clan of the Fiery Cross has turned its hatred on a Chinese-American boy named Tommy Lee and his family because Tommy has replaced a white kid as the starting pitcher for the local baseball team. The Clan believes that America is for 100% white, protestant Americans. Lee and his family don't fit the mold.

The show is just as zany and action-packed as you'd expect for a radio program of this era — with cliffhangers at the end of each 15-minute episode. Superman must save Tommy and his family from kidnappings, a bicycle bomb, drowning, and a sniper's bullets among other things. In the end, Superman of course brings the Clan and its leader, the Grand Scorpion, to justice.

It might sound a little hokey, but the show did several important things. At multiple points, Superman equates the actions and ideals of the Clan with those of the Nazis — a group of villains he, and millions of Americans, had just waged a war against. The program also exposed the Clan's grift. In one crucial scene, the head of the national Clan lectures the Grand Scorpion for jeopardizing an upcoming membership drive with his foolish, violent pursuit of the Lee family. The radio feature makes it clear that this Clan is really in it for the money. The men suckered in by the jerks at the top look entirely foolish.

The Man of Steel gets under the Klan's skin

The show had an undeniable effect. Kennedy reported back that in the weeks "Superman versus the Clan of the Fiery Cross" was on the air, Klansmen wanted to talk about little else. The men saw straight through the thin costuming, and became increasingly irritated by the bumbling incompetent portrayal. Some expressed embarrassment at having come home to find neighborhood kids dressed in bed sheets and capes playing Superman versus the Clan. Others were afraid of what their own children might think of if they discovered their Klan robes and hood. According to Kennedy, membership attendance in his Klavern fell precipitously over the course of the program and never recovered.

In response, the head of the Georgia Klans, Samuel Green, attempted a boycott of Kellogg, one of Superman's sponsors, and even purportedly placed a $1000-per-pound bounty on the "unknown rat" who had exposed the Klan to so much ridicule.

The radio program earned acclaim from social justice advocates of the time for its ability to show children the evils of bigotry. Even more importantly, it demonstrated the power of fiction as a medium to battle real-world injustice and oppression — a fight comic book stories of all forms continue to this day.

Superman victorious

Based on information provided by Kennedy and others, the Ku Klux Klan in Georgia was forced to surrender its charter after the IRS came after it for back taxes totalling $700,000. Beset by fines, legal fees, and public scorn, the third wave of the KKK never materialized, and while the Klan would rise to public consciousness again during the 1950s and '60s, it never again reached the heights of power it attained in the 1930s.

Many others deserve credit for taking out the Klan, including the ACLU, the anti-defamation league, and countless unnamed Black Americans who had to deal with the fight on a personal level. With all that trauma as the backdrop, it's still somehow ennobling to think about Superman flying off the page and out of the radio waves to play at least a small role in the downfall of one of the most hateful villains in American history.