The Controversial History Of The ACLU

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) defended Oliver North during the Iran-Contra scandal, violent criminals, the Westboro Baptist Church, literal Nazis, and Guantanamo Bay inmates. Over their 100-history, the ACLU's grown into the largest civil rights organization in the country and has been in too many controversial cases to count, which is practically its raison d'être — to challenge and force the government into protecting the civil liberties of everyone in America.

From abortion to guns to religion to free speech, the ACLU has been at the center of America's most contentious issues. According to television character, Dr. Gregory House, (Season 4, episode 9), "If nobody hates you, you're doing something wrong." By that metric, the ACLU seems to have been doing a lot of things right — they've managed to anger racists, antiracists, atheists, Catholics, communists, nationalists, Republicans, Democrats, and everyone in between at one point or another.

The ACLU was formed because of anarchist terrorists

Anarchists were real busy when the 20th century began. Over the last few decades, anarchist terrorists had become, according to Idaho University History professor Richard Spence, "...the greatest threat to established order. Anarchists carried out a string of assassinations and bombings from the 1870s through the early 1920s." They'd killed a United States president, a tsar, an empress, multiple kings and prime ministers, hundreds of police officers and government officials, and even more innocent bystanders in many countries.

After anarchists planted a string of bombs across the country in 1919, U.S. Attorney General Mitchell Palmer, whose house was also bombed, created a new organization to gather intelligence on anarchists, communists, and the types of foreigners associated with both. In 1920, the Department of Justice coordinated with local police all across the country in simultaneous raids on thousands of people, arresting and deporting many of them. "The 'Palmer Raids' were certainly not a bright spot for the young Bureau," says the FBI today.

The American Civil Liberties Union was formed later that year in almost direct response to the Palmer Raids. A liberal pacifist named Roger Nash Baldwin, "with the help of two conservative attorneys" says ThoughtCo, and a number of other anti-racist, pro-labor, anti-war, and/or free speech activists saw a need for a nonpartisan organization to agitate against the government in defense of individual liberties.

The ACLU defended anarchists

Italians Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti immigrated to the U.S. in 1908 where, as Jacobin describes, "they found anarchism and became dedicated followers of Luigi Galleani, a charismatic, anti-organizational, militant anarchist who preached the overthrow of capitalism and government by any means." It was the Galleanisti who had exploded bombs at the homes of government officials, including Attorney General Mitchell Palmer in 1919.

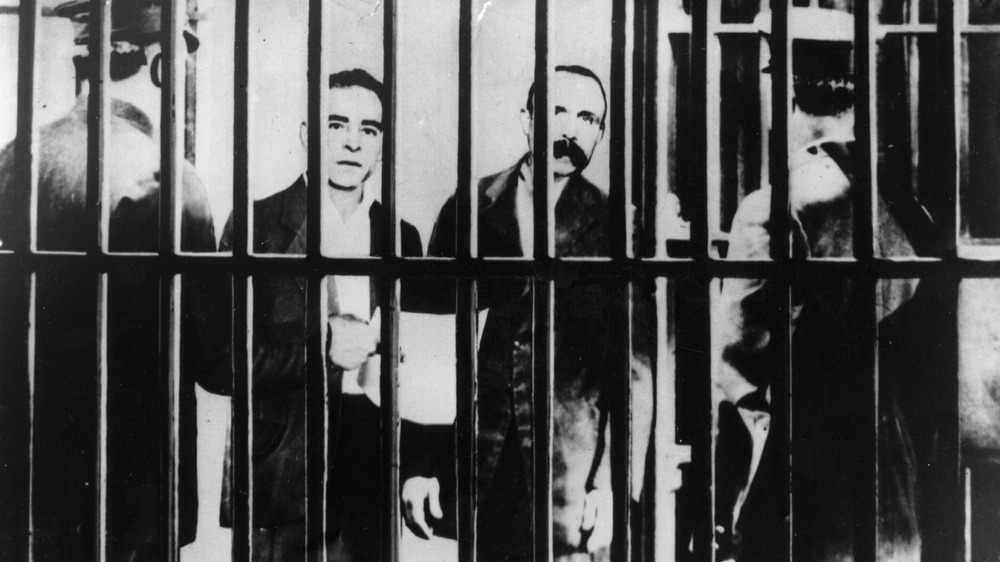

The following year, after the Palmer Raids, Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested in Massachusetts in connection to a recent robbery and murder. Not only were both men armed, one also had a flyer for an anarchist protest on him. Even if that weren't the case, as Jacobin quotes one of the ACLU lawyers, "an Italian accused of a murder in Massachusetts stands about as much a chance of getting a fair trial as a Black man accused of rape in the south."

"Experts continue to debate whether one or both men committed armed robbery and murder," admits the Massachusetts state government. "On one subject, however, there should be no debate. Sacco and Vanzetti did not receive a fair trial." They were both convicted after a trial in which far more evidence was presented about their anarchism than about the murder and robbery they were accused of. Their 1927 execution brought tens of thousands of protesters to the streets of cities all over the world.

ACLU talks a teacher into getting arrested to defend evolution

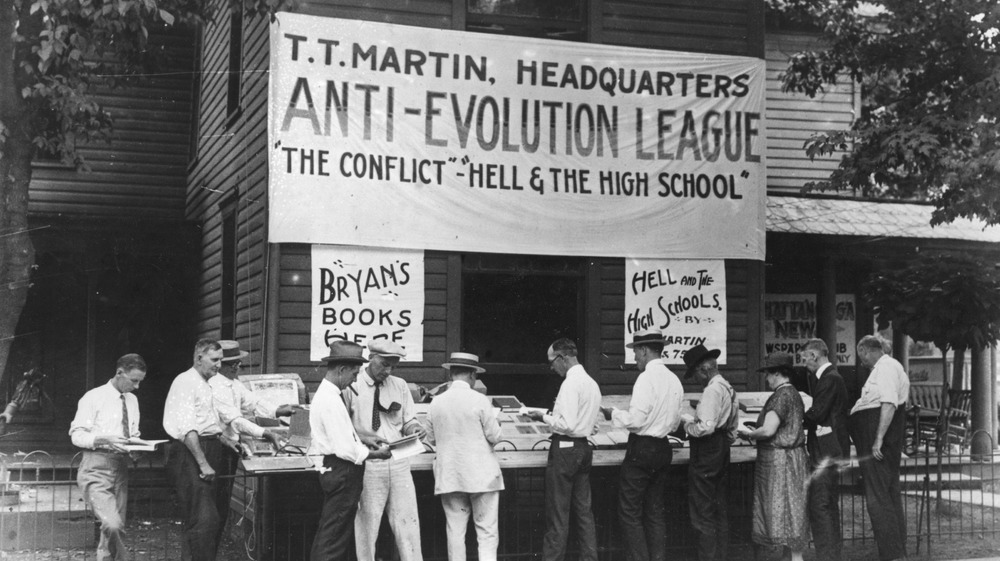

According to Gallup, a majority of Americans today believe in the theory of evolution. However this was far different 100 years ago when there was a very strong and organized opposition to evolution being taught in schools, As former congressman and ex-Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan said in a 1921 speech, per NPR, "better to trust in the Rock of Ages, than to know the age of the rocks."

In 1925 the Tennessee legislature banned classrooms in the state from teaching "any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible." The ACLU thought the law was flagrantly unconstitutional and a month and a half later ran an ad in a Chattanooga newspaper "looking for a Tennessee teacher who is willing to accept our services in testing this law in the courts."

A young science teacher and football coach named John T. Scopes in a small town named Dayton volunteered, was indicted for teaching evolution, and the ACLU came to his defense. The resulting trial was a media circus as journalists and broadcasters descended on Dayton. The whole country was glued to the trial, which Scopes lost and was fined $100. The ACLU had planned to challenge it all the way to the Supreme Court, but Scopes' conviction was overturned on a technicality, and the constitutionality of teaching evolution remains unresolved.

ACLU defends Black boys in Jim Crow Alabama

In 1931 a brawl erupted on an Alabama train between a group of white boys and a group of Black boys, explains PBS. When the train stopped in Jackson County, nine black boys and young men were arrested and charged with assault, the youngest of them only 13 years old. Two white women later accused them of sexual assault as well. Their trial was held in Scottsboro, where they were all convicted in under three weeks and, except the 13 year old, sentenced to death. The case sparked national outrage, and the ACLU joined their defense team for the appeals.

The subsequent appeal trials were as shocking in their revelations as their original trial was shameful in its truncation. One of the white women recanted her accusation, and the other's testimony was also discredited on the stand. The systematic failure to provide a fair process for accused was inexcusable. In the end, all of them had their executions vacated, although most of the convictions were upheld and many of them remained in prison for years. All of their nine lives were shattered. The arrest of the Scottsboro Boys was legalized racism, and their trial a farce, but the ACLU points out that in the end their case "established an important right for defendants of all races in capital cases from that moment on."

ACLU fought for Japanese-Americans during WWII

People tend to get nervous when things explode, frequently asking the government to do "something" to stop them exploding. Unfortunately, that something often turns out to be unfair or just plain racist. For instance, "fears of espionage and subversion during World War I fed nativist sentiment and xenophobia," explains Springfield Technical College's "Our Plural History" project, leading to bigoted laws that helped execute Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. When America entered into the World War II, it was through a long morning of explosions at Pearl Harbor.

America was at war with the Japanese. A determined, aggressive, alien enemy. And the government had to do something. So President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, meaning "approximately 122,000 men, women, and children were moved to assembly centers." Explains the National Archives' "Our Documents" project, "Nearly 70,000 of the evacuees were American citizens. The government made no charges against them, nor could they appeal their incarceration."

The ACLU protested the move and moved to sue the government. Most famously they argued before the Supreme Court on behalf of Fred Korematsu, an American citizen arrested for ignoring the evacuation orders he was given. The case was lost though, the detention camps remained open, and "in fact," says the Princeton Library, "the last detention center was not shuttered until 1946." Forty-two years later the government officially apologized and paid reparations to the Americans unjustly held by their own government.

ACLU defended Nazis in the 1930s

Believe it or not but fascism was pretty popular in the 1930s and not just in the usual German and Italian haunts. The specter of national socialism floated visibly in the politics of Greece, Spain, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the U.S. was no different. Homegrown American fascist groups were commonplace. As the History Reader describes, "There was a substantial counter culture of loyalists to Hitler" in the U.S. at the time. The leading group, the German-American Bund, had as many as 25,000 dues-paying members, including some 8,000 Storm Troopers. The Silver Shirts claimed another 15,000 members. Prominent Americans like Charles Lindbergh and Henry Ford spoke fondly of Hitler, and a 1939 Bund rally in Madison Square Garden was filled with 20,000 Sieg Heil-ing American citizens.

The Bund, says the Holocaust Encyclopedia, "carried out active propaganda for its causes, published magazines and brochures, organized demonstrations, and maintained a number of youth camps" — activity which many local officials tried to curtail by siccing the police on them or passing laws against them. When New Jersey banned "propaganda inciting religious or racial hatred," as the New Jersey ACLU itself explains, they fought the law "saying civil rights were guaranteed to all." ACLU lawyer Arthur Hays was actually Jewish himself and said to The New York Times when asked, "It is better to have them express this animosity openly than have it suppressed and (go) underground."

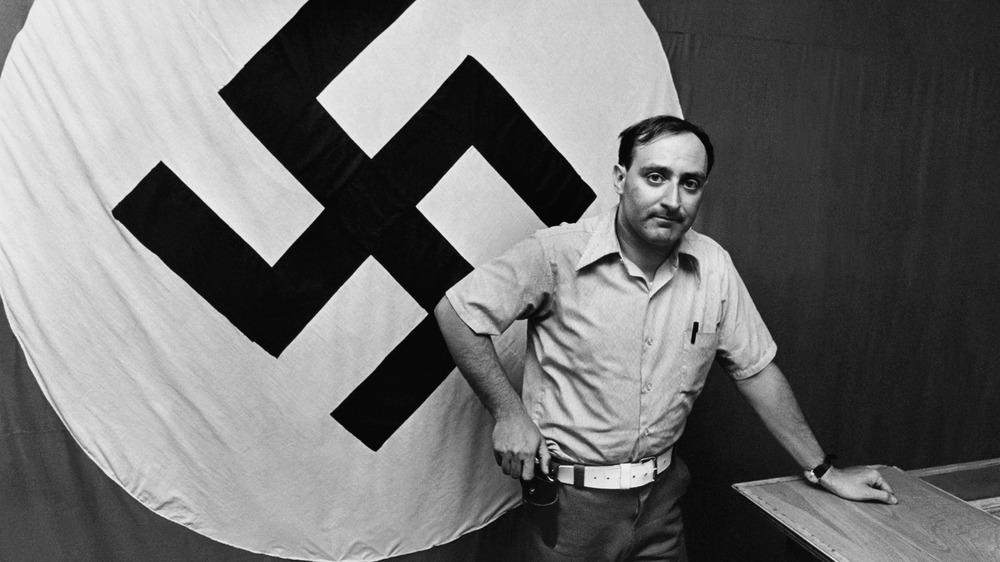

ACLU defended Nazis in the 1970s

A neighborhood park in 1970s Chicago, said former ACLU National Director Ira Glasser to Reason Magazine, "became a place where neo-Nazis and civil rights activists would frequently clash in contiguous demonstrations." The city of Chicago got tired of spending money and time on monitoring the park so instead it basically banned demonstrations there. The civil rights group and the neo-Nazis each went to the ACLU to fight the law, but the civil rights folks got there first. The racist group didn't want to wait — as Reason's Nick Gillespie observed, "Neo-Nazis are very impatient and thin-skinned" — and went hunting for a place to sue on their own.

They sent letters to a dozen Chicago suburbs declaring their intent to march in their towns. Skokie was the only town to respond, fiercely rejecting the idea. Skokie was home to tens of thousands of Jews and, according to The New York Times, the largest concentration of Holocaust survivors outside of Israel. The town passed laws specifically against the neo-Nazis, who now had a reason to sue them. And, said Glasser, "it was only when Skokie went to court that we were then compelled to represent the Nazis, because we were already representing the Martin Luther King Jr. Association on the same issue." Ironically perhaps, the case attracted tens of thousands of counter-protesters, causing the neo-Nazis to back out and never even march in Skokie.

The ACLU said students don't have to say the Pledge of Allegiance

Part of the principle of free expression, the ACLU has argued over the years, is that you also cannot be forced to say something. During World War II, many states made the Pledge of Allegiance or similar patriotic ritual compulsory in schools, and in 1943, a family of Jehovah's Witnesses in West Virginia sued the state Board of Education over mandatory flag salutes. The ACLU supported the case, which eventually ended up before the Supreme Court, who, as the Massachusetts ACLU explains, held that the constitution "protects students who engage in silent protest or express dissent during the recitation of the pledge or during other patriotic ceremonies."

"The famous decision established that public school students had First Amendment rights," explains the Freedom Forum Institute, yet still the ACLU has been involved in several lawsuits over the years arguing that forcing students to recite the Pledge of Allegiance unconstitutional. Especially during the 1990s, explains the legal website FindLaw, the ACLU "repeatedly defended students in school districts who suffered reprisals for failing to participate in the Pledge of Allegiance." Every state chapter of the ACLU has a section on its website explaining students' rights and warning school districts that "state-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism."

ACLU defended the alt-right in Charlottesville

In 2017 a group of Confederate apologists, Klansmen, neo-Nazis, and white supremacists intended to hold a "Unite the Right" rally in Charlottesville, Va. They applied for, and were granted, a permit to do so. When the city realized who exactly was marching, they revoked the permit. The groups sued and the ACLU, seeing that the many counter-protester groups' permits had not been touched, joined the case. "We were, unfortunately, sued by the ACLU," complained the Virginia governor to NPR after the event. The march went on as scheduled, hundreds of white nationalists were confronted by thousands of counter-protesters, violence erupted, and ultimately, a car "plowed into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing one and injuring 19."

Many people were aghast at the ACLU defending the alt-right even before the tragedy unfolded at the march. "Strange as it may seem for a group widely loved by liberals," explained Vox before it began, "the ACLU helped ensure that this weekend's racist protests in Charlottesville went on as planned."

Concerns that the ACLU was enabling hate speech and giving a platform to racists were widespread. The ACLU of Virginia was as dismayed as everyone else and vehemently denied that they contributed to the violence. "We asked the city to adhere to the U.S. Constitution and ensure people's safety at the protest." Said the ACLU, noting that police were present and deliberately refused to act until it was too late, "It failed to do so."

ACLU is accused of changing its mind on free speech

The events of Charlottesville prompted a debate in the broader civil liberties community as well as within the ACLU itself. As Vox reported afterwards, "The backlash has already spurred other ACLU chapters to declare that they don't believe free-speech protections apply to events like the one in Charlottesville." A board member of the Virginia ACLU publicly announced his resignation on Twitter. "What's legal and what's right are sometimes different," reported ABC. "I won't be a fig leaf for Nazis."

Proving that you can't please everyone, the national ACLU announced a correction to their policy. From now on, they will not accept cases on behalf of people who wish to have firearms at their events. This angered many civil libertarians, and the organization was accused of abandoning its mission of protecting individual's rights. "Until now," Vox quoted defense attorney Scott Greenfield, the ACLU had "never quite come out and announced that they will refuse to defend a constitutional right."

The ACLU says it merely modified the guidelines by which they will choose who to represent in the future. Critics say it reflects a dilution of the importance of free speech to the ACLU and point to a leaked internal memo about those guidelines, about which a former board member said in the Wall Street Journal, "If the Supreme Court adopted the ACLU's balancing test, it would greatly expand government power to restrict speech."

ACLU fought against stronger due process

In November of 2018, the U.S. Secretary of Education changed the rules on how sexual assault would be addressed on college campuses. University administrators now have to follow a procedure closer to a criminal court, giving the accused the right to defend themselves. The ACLU blasted the decision, "Roll Back Civil Rights Protections For Students Filing Complaints of Sexual Harassment or Assault" it said in a blog post, following up on Twitter saying that "It promotes an unfair process, inappropriately favoring the accused." This shocked many civil rights advocates who contend that the ACLU is sacrificing equal protection and having a double standard.

"The ACLU has long defended the rights of accused terrorists, criminals, neo-Nazis, and the Westboro Baptist Church," said libertarian Reason magazine, "...the presumption of innocence seem to be falling off the organization's radar as things that should be defended." Journalist Conor Friedersdorf wrote bluntly in The Atlantic that "the ACLU is weakening principles that protect the most vulnerable among us." The ACLU says that what happens on college campuses are not criminal trials, and different standards can apply. Others point out that false assault accusations are most often used against minorities (like immigrants and people of color), and that this is exactly why equal protection under the law was codified into our culture to begin with.

ACLU accused of not defending religious freedom

In addition to accusations of giving up on free speech, the ACLU is also coming under increasing suggestions that it has abandoned another key part of the First Amendment — freedom of religion. Montse Alvarado, the executive director of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, said in USA Today that by "Attacking a Catholic adoption agency" and "sitting on the sidelines while three American Muslim men...are defending their own religious freedom before the Supreme Court," that the ACLU is ignoring a key civil liberty for over a hundred million Americans.

Tim Schultz, president of the 1st Amendment Partnership, wrote in The Hill that the ACLU is "increasingly hostile to actual religious freedom" and "has refused to embrace religious freedom even when doing so would help its own clients." Preventing churches and religious charities from hiring and offering their services to those who fit their religious criteria is an abridgment of their First Amendment rights, Schultz and others like him argue.

The ACLU points out that they do defend religious liberty, like when they defended Amish communities in Michigan, reports US News, for not having plumbing. Defenders of the civil rights group retort that religious liberty must coexist with other liberties and social values. Critics like Schultz suggest that such logic "would render the Bill of Rights meaningless."