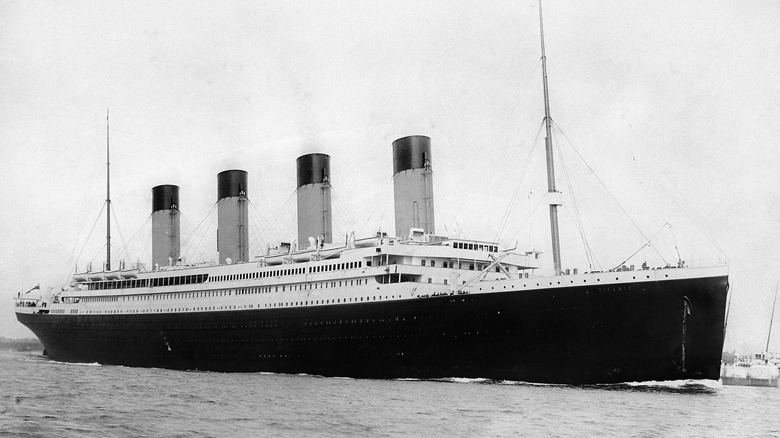

What If The Titanic Never Sank?

Even now, over 110 years after the Titanic sunk on her maiden voyage, the ship remains in memory. In 1912, over 100,000 people joined the crowd of onlookers when the ship and its 2,223 passengers and crew set out from Southampton, England to New York City. The vessel was grand, luxurious, and touted as "practically unsinkable," all of which added to the shock when it hit an iceberg four days after it launched. 1,517 of those on board didn't return home, including 832 passengers and 685 crew members. But perhaps even more shockingly, only a little over 53% of those on board could have survived a shipwreck at all given its number of lifeboats.

So yes, not only did the Titanic go down as one of the worst maritime disasters in history, but it didn't have to end so tragically. Even if the ship had hit an iceberg, more lives could have been saved if proper precautions had been in place. In addition to a dearth of lifeboats on board, there weren't enough lifebuoys. There also wasn't proper training in case of an emergency, and some of the ship's crew wasn't equipped with gear like binoculars and searchlights.

Ultimately, the sinking of the Titanic left a legacy of revamped oceanic safety laws. If the ship hadn't sunk, these laws would have never been made (at least not as soon). As for the Titanic itself, it might have lived out its service until retirement — or more likely gotten destroyed or commandeered in a war.

[Featured image by Francis Godolphin Osbourne Stuart via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

Decommissioned after decades of service

Folks might forget that the Titanic wasn't a cruise ship even though many of the ship's accommodations were on par with modern-day cruise ships. It held a swimming pool, squash courts, a Turkish bath, a gym, a barber shop, and more. Even so, there were fancier liners in operation at the time, but those had lower quality class areas in comparison to the Titanic. And yet it was categorized as an ocean liner because it carried cargo as well as people.

It's reasonable to assume that if the Titanic never sank it would have continued crossing back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean, carrying people and cargo, until it got too old to be seaworthy and was decommissioned. Its novelty would have worn off, its amenities become as commonplace as others, newer ships would have been built, and even the size of the ship would end up unremarkable. On this point, Germany's SS Imperator was larger, heavier, and could hold more passengers than the Titanic, and it hit the waves in 1913 — one year after the doomed British vessel. The SS Vaterland, which launched the next year in 1914, was even bigger. So on it went for decades. The most long-lasting of the Titanic's sister ships — the Olympic — struggled to keep up with newer, faster ships. She was retired in 1935, and dismantled by 1937.

Destroyed or claimed in a global conflict

The early 20th-century era in which the Titanic launched might stand out to the reader. World War I started in 1914, two years after the Titanic set out. World War II started less than 30 years later in 1941. World War I and its submarines marked a new era for naval warfare, one where German U-boats alone sunk over 5,000 ships. That's a staggering amount, but one superseded by World War II, which saw over 15,000 ships sunk before the war ended. Those 15,000 ships, it must be noted, contained over 500,000 people.

If the Titanic survived its maiden voyage, who's to say it wouldn't have been sunk in a matter of years? As a large ship that traveled between two major countries, the U.K. and the U.S. — both of which were involved in World War I against Germany and its above-mentioned U-boats — it would have made an easy target. A mine or torpedo sunk the Titanic's other sister ship, the Britannic, in 1916. And even if the Titanic survived World War I and wasn't decommissioned like the Olympic before World War II began, how likely is it that the vessel would have survived another global conflict on an even greater, more destructive scale?

If the Titanic hadn't been destroyed at sea during this time, it might have been commandeered and converted into a military ship, anyway. This is exactly what happened to ships like the aforementioned SS Vaterland.

[Featured image by Willy Stöwer Stuart via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

More lax safety regulations

When the Titanic sunk beneath the ocean it took the lives of over 1,500 people and also gave rise to a new, upgraded regime of safety regulations regarding ocean vessels, particularly when it came to lifeboats. The Titanic did have enough life jackets for everyone on board, at 3,560. But given oceanic weather conditions and the cold temperature of much of Earth's oceans (the Titanic hit an iceberg, remember), life jackets wouldn't have been enough, anyway.

At the time the Titanic launched in 1912 there were a couple of prevailing pieces of legislation that determined the quantity of lifeboats on board a ship: the Merchant Shipping Act of 1894 and the Merchant Shipping Act of 1906. In total, as the Library of Congress explains, these two acts outlined lifeboat numbers based on ship weight, with 10,000 tons being the maximum (equaling 16 lifeboats for 990 people). The Titanic weighed over 46,000 tons, however, and no one thought to equip it with more lifeboats.

Both the U.K.'s Titanic Wreck Commissioner and a U.S. Senate Investigation came to a very common-sense conclusion: The quantity of lifeboats should be based on the number of passengers, not the weight of a ship. Lifeboat safety drills also became mandatory following the sinking of the Titanic, as did rules regarding onboard radios. While this seems like a no-brainer, we could argue that if the Titanic didn't sink, it might've taken another, subsequent disaster to yield the same results.

Less safe ship design

The sinking of the Titanic also led to safer ship designs. Just like changes to lifeboat rules and emergency drills, changes to ship designs might have happened anyway, but at a later time and perhaps after even more lives had been lost.

The Titanic wasn't necessarily poorly designed. It's more that steel ships like it had only been in use for a short time — since the late 1800s — before it was built. As it stood, it could feasibly take on water and stay afloat, but only if it flooded in a specific way. The bottom deck of the Titanic was split into compartments separated by bulkheads that ran along the longitudinal axis connecting the front (bow) and back (stern) sides of the ship. If three consecutive, connected compartments took on water, the ship was fine — unless certain combinations of boiler rooms, engine rooms, and dynamo got flooded, too. However, even in the best case scenario the ship could have only stayed above water for two to three days.

In the wake of the Titanic disaster ships were designed with double hull layers, not just one. Also, the bulkheads were raised all the way to the ceilings of their decks rather than only partway up. This could completely contain water in a given compartment in the event of an emergency.

Less regulated maritime laws

Much like ship design and emergency protocols, the sinking of the Titanic had a huge impact on maritime laws related to oceanic safety. This is especially true because ocean waters are largely international, and maintaining proper safety necessitates the involvement of multiple nations and governments. If the Titanic hadn't sunk, such new regulations wouldn't have happened — at least not as soon as they did.

Along these lines, the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) met in London in 1913, the year after the Titanic disaster. Thirteen nations joined this meeting and signed its treaty, which resulted in several maritime law changes. Shipping companies, firstly, had to disclose the routes that they intended to take. This meant that water patrols could more easily track the location of vessels if those vessels ran into trouble. Then, 1914 saw the creation of the International Ice Patrol, a division of the United States Coast Guard and now U.S. Homeland Security. The goal of the division, simply put, is to monitor and report the locations of icebergs — like the one the Titanic struck — to help increase ship safety.

Even by then, though, U.S. Congress quickly passed the Radio Act of 1912, which allowed for 24-hour radio communication between operators and ships at sea and created a separate frequency just for distress calls. The later Merchant Marine Act of 1920 allowed seamen to sue employers for injuries suffered while at sea.