The Most Disturbing Thing About The Titanic Sinking Isn't What You Think

Everyone knows the story of the sinking of the Titanic, even if in your head the story will forever be accompanied by that super-irritating Celine Dion song. Even before Jack and Rose, though, the Titanic was a part of human consciousness — the terrifyingly true story of the "unsinkable ship" that sank anyway, taking the lives of more than 1,500 people.

That's horrible and tragic and shocking, but it's not as deeply disturbing as what happened before the ship slipped into the North Atlantic. There were actually numerous opportunities to either avert the tragedy altogether or simply make it less costly in terms of lives lost, and it was only human error — sometimes carelessness, sometimes laziness, and sometimes callousness — that made the disaster as bad as it ended up being. So set aside all your preconceived notions about what makes the story of the Titanic so disturbing and get ready for some extra-disturbing what-ifs.

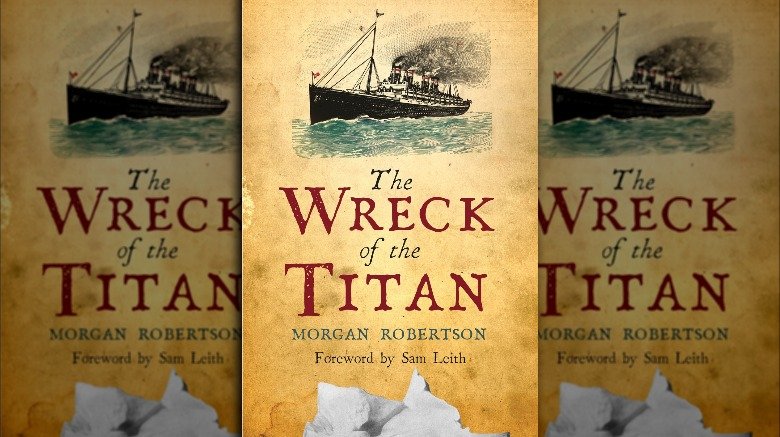

The Wreck of the Titan ... that's right, the Titan

It's probably safe to say that the Titanic's designers and builders didn't do much reading of popular fiction. If they had, they might have picked up a little piece of literature entitled Futility or the Wreck of the Titan, and then they would have been all "Daaaang, let's make sure none of this happens to our ship." At the very least, maybe they would have chosen a different name. You know, something like the Small and Humble and Not Tempting Fate One Bit.

According to the Liverpool Museums, The Wreck of the Titan contained some seriously eerie similarities to the Titanic — the fictional Titan was "the largest craft afloat," "equal to that of a first class hotel," and "unsinkable." Sound familiar? Like the Titanic, the fictional Titan was about 400 nautical miles away from Newfoundland when it struck an iceberg in the North Atlantic. And like the Titanic, the Titan didn't have enough lifeboats for everyone on board. And also, "Titan," "Titanic," we don't have to point out that there's only a two-letter difference between those two names, do we?

It's such a bizarre coincidence that you've almost got to wonder if someone actually printed the wrong date on the book just to freak everyone out. The Liverpool Museums seem convinced, though. Their copy was a reprint from 1912, after the disaster — but the original publication is 1898, 14 years before the Titanic went down. Creepy.

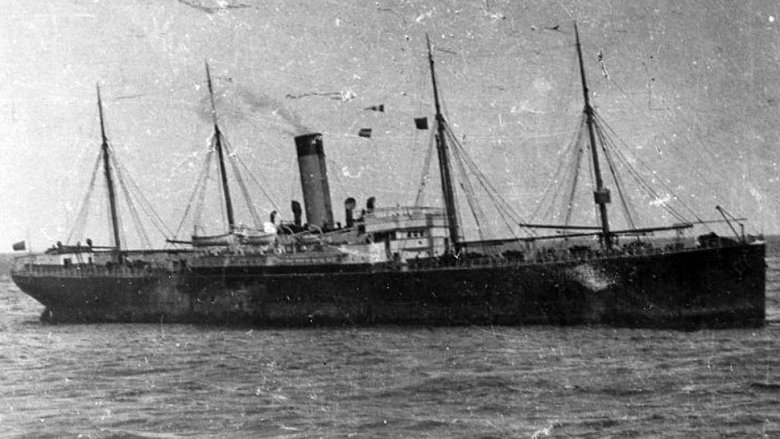

There was a ship nearby that might have saved everyone

Contrary to what you've probably heard, the Titanic was not the first ship in history to use the S.O.S. distress call, but wireless communication was still pretty new, which meant there weren't really any requirements for 24-hour monitoring or anything. That explains why no one onboard the Californian, which was somewhere between 8 and 12 miles away from the Titanic, heard its distress calls. According to Encyclopedia Titanica, the Californian had only one wireless operator, and he'd switched off his equipment and gone to bed. If he hadn't, he would have known within about 15 minutes of the collision — when the first distress call was sent — that the Titanic was in trouble.

The Californian was surrounded by ice and stopped for the night, so if it had left immediately it probably would have taken 30 minutes to get through the ice, and another 30 to 60 minutes to reach the Titanic, depending on how far away it actually was. It took 2 hours and 40 minutes for the Titanic to actually sink, so the crew of the Californian would have had more than an hour to collect passengers. They might have even been able to save everyone.

Alas, it didn't go that way. The crew did see the Titanic's distress rockets, but their captain dismissed them as non-emergency signals meant for some other boat. By the time the Californian turned the radio on the next morning, there was nothing left of the Titanic but bodies floating in the sea.

You didn't need this key, did you?

The two guys in the crow's nest didn't see the iceberg until it was too late. But why? One theory says the sea was too calm and the lookouts weren't able to see waves breaking at the base of the iceberg. According to another theory, the crow's nest didn't have any binoculars. Except that one isn't a theory; it's a really unfortunate fact.

So let's get this straight, the Titanic had rowing machines, an electric horse, a squash court, and a heated swimming pool, but it didn't have binoculars onboard? Actually it did, but they were unhelpfully locked away in a cabinet and no one could find the key. It seems that the key was in David Blair's pocket, and David Blair had disembarked in Southampton.

According to the Telegraph, Blair served as the ship's second officer between Belfast and Southampton, but at the last minute the White Star Line decided to replace him. In his rush to disembark, he forgot to give the key to his replacement.

You can look at this a couple of ways — the last-minute reassignment saved Blair's life or the last-minute reassignment didn't save Blair's life because it was responsible for the entire disaster. If you believe binoculars could have helped the crew avoid the iceberg, then Blair's life was never really in any danger. On the other hand, his failure to turn over that key may have doomed more than 1,500 people, so there's that.

The tragic story of a passenger who had already survived one shipwreck

Every life lost on the Titanic was a tragedy, from third-class Jack to first-class Rose, except Rose didn't actually die and oh yeah, they're fictional. But even though all the real-life stories are devastating, some are harder to read than others. One especially awful story is about Ramon Artagaveytia, who survived the sinking of the America, which the Encyclopedia Titanica says went down off the coast of Uruguay in 1871. According to his own letters, Artagaveytia may have suffered from PTSD after his first shipwreck experience. When traveling, he often had nightmares of fellow passengers screaming "fire" and of standing on deck in his lifebelt.

After years of this, he wrote to a cousin about his faith in the Titanic: "At last I will be able to travel and above all, I will be able to sleep calm. ... You can't imagine, Enrique, the security the telegraph gives. When the America sank ... nobody answered to the lights asking for help. ... Now, with a telephone on board, that won't happen again. We can communicate instantly with the whole world." Unless the wireless operators shut off their machines and go to bed.

Artagaveytia's body was recovered about a week after the sinking.

No one ever talks about the guys who died keeping the lights on

No one could have really saved everyone on the Titanic. Still, there were plenty of acts of heroism that night, some of which directly or indirectly saved individual lives. The heroic band played until the very end. The chief baker literally threw reluctant women into lifeboats, and first-class passenger Benjamin Guggenheim refused to get into a lifeboat, famously saying, "No woman shall be left aboard this ship because Ben Guggenheim was a coward" before sitting down with a glass of brandy and watching the water rise.

Some acts of heroism weren't so well-publicized. According to the Guardian, there were 35 engineers onboard Titanic, and the reason why we have no firsthand accounts of what they were doing during the ship's final moments is because they all died.

What we do know is that they stayed at their posts and kept the lights on. That's a bigger deal than it might at first sound like — remember there is no artificial light on the North Atlantic and the moon was barely a sliver, so the electric lights made it possible for the crew to load the lifeboats and keep passengers from panicking. Power also made it possible for the radio operators to continue transmitting distress signals, though we are sadly all too aware of how little help that actually was, though it was certainly not unheroic.

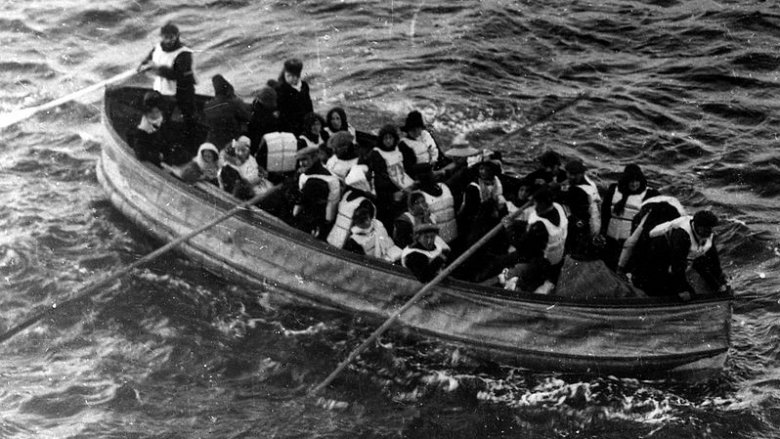

Let's talk about those lifeboats for a second

Everyone knows there weren't enough lifeboats on the Titanic, but when you look at the actual numbers you become aware of just how negligent the White Star Line actually was. According to Irish Central, Titanic had around 2,223 passengers onboard (no one knows the exact number because some people were traveling incognito, some didn't use their tickets, and others might have stowed away), and the official capacity of the lifeboats was 1,178. Yet there were only 712 survivors ... why is that? Many of the boats were launched at half capacity, which seems crazy until you remember that everyone, from the passengers to the crew, thought the Titanic was unsinkable and that filling the boats was simply a precaution. Many of the officers in charge of loading the boats were following the strict "women and children only" guideline, which meant when they couldn't find enough women and children to fill the seats they would launch them half full rather than fill the seats with men.

So why did the Titanic have only 20 lifeboats when it needed at least twice that many? There was room for 64 boats, but chief designer Alexander Carlisle planned for just 48. Still, that would have been enough to save everyone — provided they'd been properly loaded, of course. But someone in the ranks of decision makers decided to reduce the number of boats to 20 because 48 would make the decks look "too cluttered." Wow.

It wasn't the steel, it was the rivets

It's hard to believe that one stupid iceberg could take down the biggest thing on the ocean. For a while, researchers wondered if the Titanic's builders might have used low-quality steel, but that theory was disproven when large pieces of the ship were recovered and tested. Sonar mapping of the side that struck the iceberg revealed only six thin tears in the hull, which would have left roughly 12 square feet open to the sea. That by itself wouldn't have been enough to sink a ship like the Titanic, which had 16 watertight compartments.

So what happened? According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology, a 1998 metallurgical and mechanical analysis of the rivets found that the wrought iron contained three times as much slag as modern standards allow for. Slag, just in case you're not a blacksmith or shipbuilder or rivet-maker, is the residue left behind after the smelting process. According to the theory, all that extra slag used in the rivets made them brittle in cold temperatures, so the iceberg just sheared off the heads as it scraped along the side of the ship. When that happened, the rivets came loose, the hull plates separated, and water came rushing in.

So shipbuilders had basically been cutting corners with low-quality materials — not to save money but because they were being asked to finish building the Titanic and both of its sister ships on an aggressive schedule.

The ship sank so undramatically that it might have seemed safer on board

In James Cameron's 1997 film, the Titanic is shown breaking in two at a high angle, with its stern well out of the water. That's probably not accurate, though. In 2008, naval architect Roger Long told U.S. News and World Report that the evidence points to a much lower-angle break of 11 degrees or so. (Later estimates say it could have been as much as 15 degrees.) The evidence can be seen in the fragments near the break, which appear to have been interrupted during the process of tearing. That's something that could only happen if the ship was able to regain buoyancy as the tear was forming. Long says the low angle might have given passengers a false sense of security — if the angle of sinking wasn't that dramatic, it's possible that passengers would have chosen to stay onboard rather than venturing out into the sea in a tiny lifeboat.

To back up the low-angle break theory, there don't seem to be reports of the huge wave that would have certainly happened if the ship had split at a high angle, and one survivor said the ship disappeared under the surface really undramatically, with nothing but a "shloop." The few eyewitnesses who did mention a high angle might have just been observing an optical illusion — once the ship's propellers were out of the water, it would have made the angle seem much more dramatic than it was.

Most of the victims didn't drown

Four days after the disaster, the Boston Globe declared, "All drowned but 868." But that was doubly inaccurate. The first problem was the number of survivors, which was actually about 700. The second was the manner of death — not everyone who died on the Titanic drowned.

The water in the North Atlantic was only 28 degrees Fahrenheit on the night of the sinking. That's 4 degrees below the freezing temperature of fresh water, so brr. According to the Encyclopedia Titanica, the Titanic didn't really have that many drowning victims. Those who remained in the ship probably drowned as the Titanic sank, but those who jumped into the water were wearing life preservers, so they were less likely to drown. And the fact that the survivors in the lifeboats heard an awful din from those in the water suggests that most of them were not drowning. Drowning happens silently — people who are drowning can't call out for help. Now, it is possible that as people lost consciousness, they inhaled water, which hastened their deaths, but that's not drowning as we understand it, it's drowning as a side effect of being incapacitated by hypothermia. So at best, we could say that people died from a combination of hypothermia and drowning, but it is also accurate to say that if the Titanic had been in the waters of the Caribbean, there wouldn't have been nearly as many deaths.

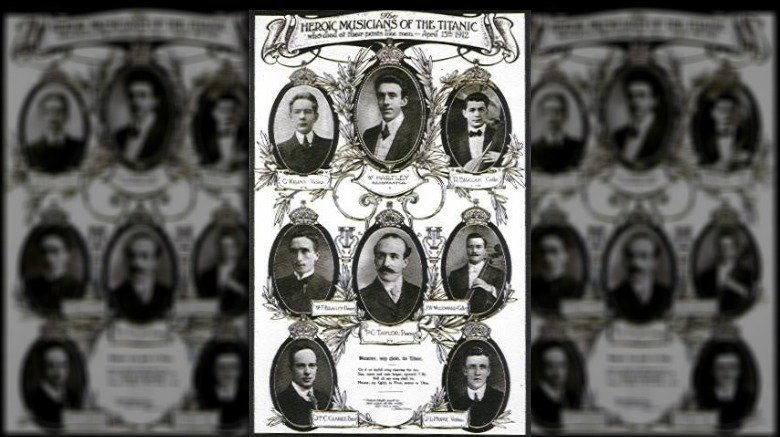

Sorry for your loss but please pay us for the ruined uniform

Now imagine that you're still reeling from the death of your loved one, who went down heroically and rather grandly, providing musical comfort to doomed passengers as his ship slowly slipped into the North Atlantic. Then you get billed for his uniform.

Yes, this story is true, and although it may not be as disturbing as some of the other things we know about the Titanic, it's a pretty ugly footnote.

According to the Vintage News, musician John Hume was booked on the Titanic through a firm called C.W. & F.N. Black. Two weeks after the sinking, Hume's father received a bill for his son's uniform, which included items like his lapel pin and White Star buttons and amounted to 14 shillings and 7 pence.

Okay, so if you spilled mustard on your uniform because you were eating a messy burger in your off-time, maybe you had that bill coming. But the Titanic's dead musicians weren't responsible for the destruction of their uniforms, and the dead musicians' parents extra-weren't responsible for the destruction of their children's uniforms, and also everyone at C.W. & F.N. Black was a terrible, terrible person.

Anyway, Hume's dad refused to pay and sent the letter to the Amalgamated Musician's Union, which published it in their newsletter. So at least the whole world (or members of the Amalgamated Musician's Union) got to see the terribleness of C.W. & F.N. Black.

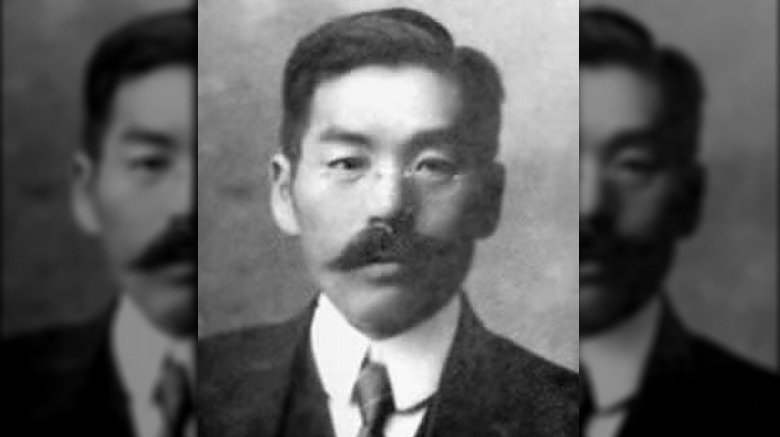

Shame on you for not dying

We'd all love to be able to say for sure what we'd have done if we were onboard the Titanic, but the truth is that none of us can ever really know whether we would be heroes or cowards. Human beings are programmed with a survival instinct — some of us may be able to overcome it, while others may be at its mercy. Still, even today human beings are often judged for what they did or did not do during a crisis. Did they run or did they help others? Sometimes those decisions, which are usually based entirely on instinct, can follow you for the rest of your life, and that's even true if circumstances largely dictated your actions.

According to the Vintage News, Masabumi Hosono was the only Japanese survivor of the Titanic, and because of that he was branded as a coward for the rest of his life. Really, though, the poor dude was just in the right place at the right time. He boarded the lifeboat simply because there were no women and children waiting in line.

Honor, duty, and shame play important roles in the Japanese culture, and when Hosono returned home he wasn't hailed as a hero but as a coward. The shame followed him the rest of his life and even beyond the grave, to the point where his family was still trying to clear his name long after his death.