The Bible Rule Almost Everyone's Clothes Break

Folks familiar with the biblical book of Leviticus might recall a whole, big list of dos and don'ts regarding things that would have concerned semi-nomadic Hebrew tribespeople thousands of years ago. There are some rather respectful rules in there like standing up when an elderly person passes nearby and treating foreigners well. There are also awesome rules like not withholding wages for people and not cussing out the blind or the deaf. There are other, curious rules like not cutting your hair "at the sides" and not cross-breeding animals. And then finally there are some head-scratchers like not picking up grapes that fall in a vineyard and, well ... not wearing clothes made from different kinds of fabric.

It's not a stretch to say that many 21st-century people might blurt, "What? Who cares?" or some such thing when thinking about wearing mixed fabrics. And to be clear, "mixed" means interwoven — like when a label from The Gap says "70% polyester and 30% rayon" or something. But like many rules laid out in Leviticus, there's a rationale at work that fits the time. The cross-bred animal thing, for instance? Well, a mixed piece of livestock in a society of herders could cause major trouble for a property owner, especially if the mother dies in childbirth.

As for the mixed fabric thing, there are a couple specific reasons. Notably, mixed-fabric garments were restricted to members of the Hebraic priestly class. This ensured that only priests could get inside the Holy Place and the Holiest of Holies inside the Hebrew tabernacle and temple, which included their treasuries.

A reminder of God's untouchability

The first five books of the Bible — the Torah to Jews and Pentateuch to Christians — are known as books of God's law for good reason. Even though Genesis starts out with a fanciful tale about cosmic creation, holy trees, talking snakes, etc., it's really a book about divine law — aka, how to follow God's rules and plan. By the time the narrative gets to the Ten Commandments in Exodus, the Bible's second book, God's rules get a bit more prescriptive. And by the time the next book, Leviticus, starts, rules get ultra, ultra specific — down to beard trimming practices, waiting 33 days after giving birth to a boy to head to religious services, not reaping to the precise edges of fields, and of course, not mixing fabric types.

Because this isn't a religious article, we're not going to speculate about Jewish or Christian theology. Rather, we're going to talk about the historical context underpinning the mixed fabric rule. Case in point: Leviticus is traditionally taken as having been written between 1,440 and 1,400 B.C.E. and describing events from 1445 to 1444 B.C.E. Garments weren't exactly simple things to make back then and necessitated sheering wool from sheep, harvesting flax plants to spin linen from their stalks, making threads, weaving them together using a loom, dyeing them, and so forth. This is partially why only the priestly class wore mixed-fabric clothing as a reminder of the untouchability of the Almighty.

Keeping non-priests out of holy places

If "God's untouchability" isn't enough of a reason for priests to wear special, mixed-fabric clothes, there's another, practical purpose: keeping other classes of people out of Hebraic holy places. The ancient Hebrew tabernacle was the precursor to the First Temple of Solomon built during Solomon's reign somewhere between 990 to 931 B.C.E. The tabernacle was a rectangular tent made of animal skins rather than a permanent, stone temple. It had two sections: the Holy Place and the Holiest of Holies. Only priests could go into the Holy Place, and only the High Priest into the Holiest of Holies, and even then only under specific conditions.

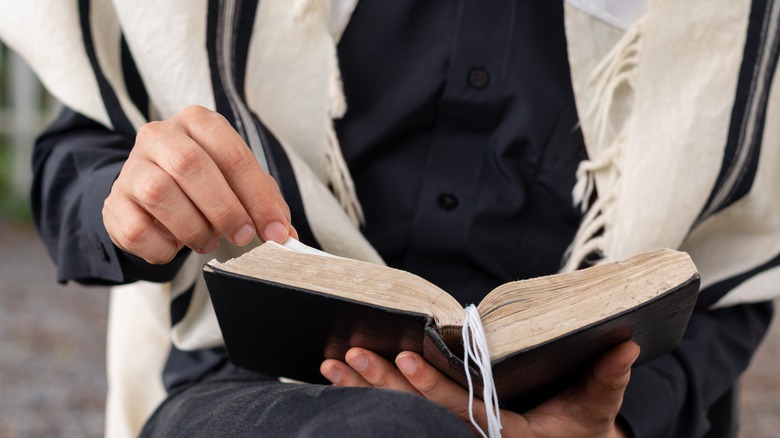

We can also look at the class structure of the ancient Hebrew society that existed at the time that rules like those in Leviticus were written. The kohanim sat at the top of society — priestly descendants of Moses' brother Aaron. In the modern day kohanim have become folks with the last name Cohen, Coen, Cohan, Kahn, and such. Under kohanim were other priests of the Levite tribe. After such religious functionaries came the rest of Hebrew society.

Wearing mixed fabrics, then, was a way to differentiate on sight those who were allowed to go into Hebrew holy places, perform rituals there, and have access to a treasury. The rule had nothing to do with maintaining purity, as some have suggested. And, it had nothing to do with morality.

No mixed wool and linen

While we've been talking about the "no mixed fabric" rule in the context of the biblical book of Leviticus, Leviticus isn't the only place in the Bible that mentions mixing fabrics. In Deuteronomy — the fifth and final book of the Torah and Pentateuch — Chapter 22 goes through a whole other list of dos and don'ts. There are rules about not disturbing the mothers of baby birds, helping oxen up if they fall, punishing false virgins, and plainly, "Do not wear clothes of wool and linen woven together."

Chabad points out that both this passage in Deuteronomy and the aforementioned passages in Leviticus describe the same kind of prohibited material, called "shatnez." The wool it describes refers only to wool from sheep and lambs, not any other animal. And the linen it describes refers to linen made from flax plants, not hemp or jute.

Forward explains how it's really Orthodox Jews who need to take care about shatnez, because they're trying to abide by the old Biblical rules in the Torah as strictly as possible. Given modern manufacturing techniques and sourcing of materials, it can be a challenge to see if clothing passes unforbidden muster. Trying on an outfit to see if it fits is okay, but buying it isn't. Separate wool and linen items are okay, just not interwoven — as we mentioned earlier. But for every other modern Jew and Christian, the mixed fabric rule belongs to the age in which the Bible was written and not the present.