The Worst Ways To Die On The Oregon Trail

Though it sounds like one large path, the Oregon Trail was a collection of different tracks moving in more or less the same direction. Generally, pioneers traveled from Missouri through the Great Plains, up into Wyoming, Idaho, and finally Oregon. It was not an easy journey, with many hazards that could injure or kill pioneers along the rather stunning estimated 2,000 miles that made up the route.

Anyone who played the computer game "The Oregon Trail" knows that the path traveled by 19th-century pioneers was a treacherous one full of messed-up stories. Around 10% of those pioneers are believed to have died before reaching their destination, perhaps quite higher than you would have thought. Disease was one of the most common causes of death, with many succumbing to contagious illnesses including cholera and dysentery. Accidents were also all too frequent.

One greatly overstated cause of death was attack by American Indians. Though travelers on the Oregon Trail were often made quite anxious by the gory, dramatic stories of wagon trains torn apart by bloodthirsty native attackers, the reality was far different. While some pioneers were attacked by Indigenous people, natives along the Oregon Trail were more apt to trade with pioneers than face off against them. Ultimately, about 400 people died in native-led attacks on the trail between 1840 and 1860, representing a very small portion of the approximately 20,000 to 30,000 people who died on the Oregon Trail. Other ways of dying, however, were all too real and awful.

Firearms accidents

A traveler on the Oregon Trail might be wracked by anxiety over any number of problems. How would they get food on the long journey? How would they defend themselves? For many, the answer was to get a gun that would allow them to hunt game and fight back against the possibility of attack by American Indians (which was itself a poorly supported fear). Yet the guns themselves may have been more dangerous than many of those fears. Many emigrants carried loaded weapons that had been placed without modern locks or cases in their wagons, and with no such thing as safeties or even proper manufacturing to keep them from discharging accidentally.

And they did just that. Other pioneers had poor aim or judgment, striking members of their traveling party when they meant only to hunt animals or ward off a supposed attacker. Some were unfamiliar with guns and simply didn't know how to handle firearms safely. One man, the ironically named John (or, in some sources, James) Shotwell, was one of the first known firearms deaths on the trail. He was killed on May 13, 1841, when, according to diarist John Bidwell, Shotwell grabbed his gun "with the muzzle towards him in such a manner that it went off and shot him near the heart — he lived about an hour and died in full possession of his senses."

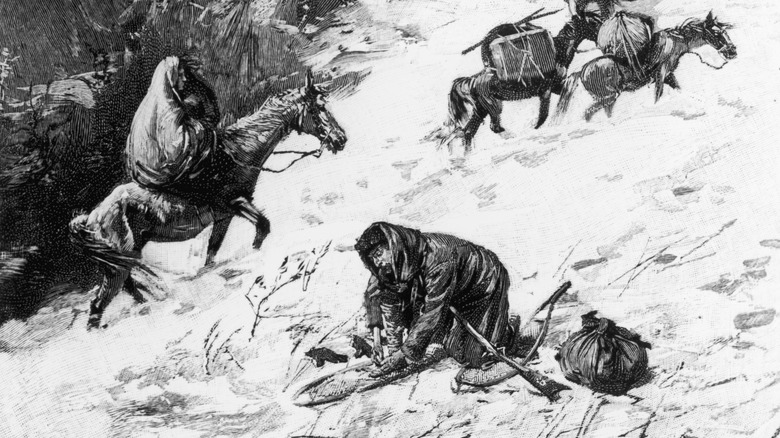

Starvation

Though starvation wasn't a leading cause of death for humans traveling the Oregon Trail — it was more likely to affect draft animals like horses and oxen — it did occasionally strike some of the most unfortunate. And when it did, the deaths that resulted could be grim indeed. Death from starvation can be a lingering process that attacks a body's organs, mutes a person's immune system, and can end with hallucinations, convulsions, and heart arrhythmia.

In September 1860, a group of 26 people in the Utter-Van Ornum wagon train, already struck by an Indigenous-led attack in Idaho, made their way to what's now Nyse, Oregon. While some were hit by further attacks, others waited for help. However, a lack of supplies caused the death of four children and pushed others to resort to cannibalism. Today, the place where they waited is starkly known as Starvation Camp.

Of course, it's all but impossible to discuss starvation during the Oregon Trail era and not mention the untold truth of the Donner Party. Technically, the group of ill-fated pioneers only traveled part of the way on the Oregon Trail, splitting off to take what they believed to be a shortcut to California. But, by late 1846, this group would find themselves stranded in the snowy Sierra Nevadas and contemplating the consumption of the dead around them. A total of 42 died, leaving behind 47 survivors and a grim legacy that surely haunted at least some later travelers on the Oregon Trail.

Drowning

Though it may have seemed laughable to a traveler in the midst of crossing the vast Great Plains or stumbling through the parched, high-altitude environments of the Rocky Mountains, one of the most dangerous things that could rear up in front of them was a river. Getting their families, animals, and supplies across a river could be a point of particular danger, especially if the waters were high and moving quickly. Some major rivers, like the Kansas and Columbia, saw hundreds of deaths from pioneers attempting to cross. Wyoming's Green River was said to be especially deadly, with some claiming that it killed at least one person a day. In 1850 alone, of the people who attempted to ford the Green River, records note 37 drowning victims. Wyoming's North Platte River was likewise a well-known killer, with cold, fast-moving waters that routinely took both human and animal lives. As traveler Francis Hardy wrote of it in June 1850, "[T]wo men were drowned yesterday & it is said 19 have been drowned in the last 11 days" (via Wyoming Historical Society).

Eventually, some crossings were made easier with bridges and ferry boats, but that didn't totally eliminate the danger. Some ferry operators, more interested in making money than upholding high standards of safety, dangerously overloaded their boats. Some attempting to cross still drowned while persuading their animals to swim, hoping to avoid the extra ferry fees charged per creature.

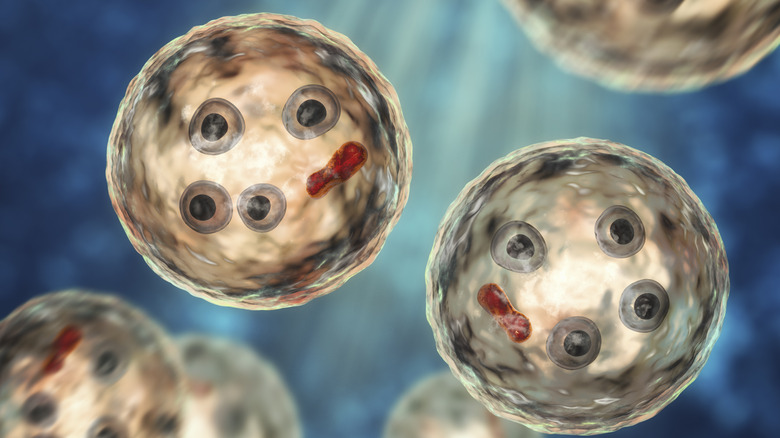

Dysentery

Today, dysentery has morphed into a strange little joke about the Oregon Trail, thanks to one morbid ending you might meet while playing the vintage "Oregon Trail" computer game. But it was hardly a laughing matter for the people who traveled the real-life route. As 19th-century historian Francis Parkman wrote in "The California and Oregon Trail," his experience with the illness proved "very effectually that a violent attack of dysentery on the prairie is a thing too serious for a joke." Parkman wrote of intense weakness and inability to keep down food, both of which brought before him the all-too-real specter of starvation.

Thankfully, Parkman recovered, but not all of the denizens of the Oregon Trail who suffered from dysentery did. The gastrointestinal infection can be caused by several different bacteria or amebic parasites that thrive in poor sanitary conditions. They can induce intense vomiting, painful abdominal cramps, and dangerous levels of dehydration. Today, the worst cases are treated by medication and intravenous fluids, but travelers on the Oregon Trail had very little access to such medical care.

To treat the ravages of the infection — which could include bloody diarrhea — some emigrants turned to a dose of castor oil. While castor oil may have helped with other stomach upsets, it was a laxative. That made it a potentially terrible choice for someone already suffering far from home, without the advantage of advanced medical care, flush toilets, or hand soap.

Eating water hemlock

Though it wasn't one of the most common ways to die on the Oregon Trail, the effects of water hemlock poisoning were surely among the most painful and grotesque ways to go. During pioneer times, it was so feared that it gained a reputation as one of the most deadly plants in the region. The active compound in water hemlock, cicutoxin, is most concentrated in its hollow roots, though cicutoxin is found in dangerous levels throughout the plant.

Of course, very few people would have knowingly consumed water hemlock. Instead, it was more likely to be mistakenly eaten by desperate pioneers facing starvation. Some appear to have confused the plant with wild parsnip, which was known to have edible roots (though it can also have caustic sap). But dining on water hemlock was a potentially deadly mistake that could induce vomiting, delirium, and a painful death.

Some have suggested that water hemlock was related to the plant that Socrates consumed to fulfill the death sentence levied against him by an ancient Athenian jury. That historical connection would have been little comfort to the unfortunate traveler who was experiencing the effects of water hemlock poisoning. Even today, water hemlock still grows in regions along the trail and remains a very real danger for pets, livestock, and the occasional human who consumes it.

Being run over by a wagon

The popular prairie schooner, a covered wagon that's now indelibly associated with the 19th-century history of the Oregon Trail, was lighter than some contraptions seen on the trail but was still a hefty vehicle. On average, it weighed about 1,300 pounds and would have been even heavier when loaded down with supplies and people, generally topping out at about 2,000 pounds.

However, pioneer wagons typically had no suspensions, meaning that many travelers found it more comfortable to get out and walk. But this put them in serious danger. While moving in and out of the wagon, clothes might catch on a piece of the vehicle, or they could stumble. They might then be thrown beneath the iron-bound wheels of the heavy, rolling wagon. Sometimes, spooked draft animals would start running and jostle people from the wagon and into the path of the deadly wheels.

Numerous accounts from the Oregon Trail tell heartbreaking stories of individuals suddenly taken by such accidents. Lucia Loraine Williams, who traveled the trail with her family in the 1850s, wrote of the tragic death of her young son Johnny, who fell from a baggage wagon in Wyoming. "Poor little fellow, we could do nothing for him," Williams later told her mother. As Williams' friend Esther Lockhart later wrote, his end was immediate: "We were the first to reach poor little Johnny, and we saw at once that he was beyond earthly aid" (via "The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey").

Childbirth

Throughout much of history, birth has been extraordinarily dangerous. The statistics on maternal mortality in the early 19th century paint a grim picture; though the best data in this era comes from Europe, it's clear that a birthing parent frequently risked deadly complications, including infections caused by unwashed doctors. It's all too easy to imagine how poorly things could go for someone whose labor went south while on the trail, far from knowledgeable folks who could have eased her pain, saved her life, or saved her baby's life.

This isn't pure conjecture, either. Take the sad case of Elizabeth Paul, who died in western Wyoming. Paul gave birth to her eighth child, a daughter, on the trail on July 27, 1862, and died soon thereafter. As fellow traveler Hamilton Scott wrote, "She has been very poorly for some time. We buried her this evening under a large pine tree and put a post and railing fence around her grave." The baby girl, named Elizabeth, died just a week later (via Wyoming Historical Society). Paul's gravesite can still be visited in the Bridger-Teton National Forest.

Even if an expecting mother on the Oregon Trail was less likely to encounter a doctor with dirty hands than her city-bound counterpart, birth remained dangerous. While she may have had access to a midwife, a pregnant woman was also likely to be missing much of her support system, be it family or helpful neighbors who could guide her through labor and the postpartum period.

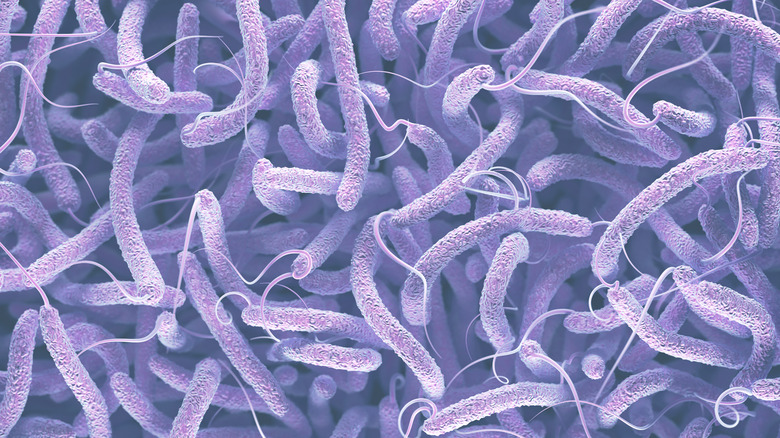

Cholera

While dysentery was certainly an awful way to go, it was also something from which people often recovered, even considering how sparse medical care could be on the Oregon Trail. But cholera was another story. Like common forms of dysentery, cholera is caused by bacteria that thrive under poor sanitary conditions. It added to the messed up history of the disease on the Oregon Trail, where pioneers, who might have been infected before they even technically started their trek, carried it along the trail and into new environments where it continued to thrive and infect new victims. Cholera proliferated in stagnant water that was infected by human and animal waste. Like dysentery, cholera also often takes its victims via diarrhea and subsequent dehydration. But where dysentery could be awful but survivable for many, cholera was known to be seriously deadly.

It moved alarmingly fast, too, as those who were infected could die within 24 hours or less. They might have seemed fine in the morning, but as the day wore on, the infection caused them to experience sudden vomiting, cramps, and convulsions. Toward the end of their ordeal, those infected with cholera might even have blue or purple faces, a side effect of dehydration and the deoxygenation of their thickened blood. Of the thousands of graves, marked or unmarked, that were laid alongside the Oregon Trail, a significant portion of them likely contain victims of cholera.

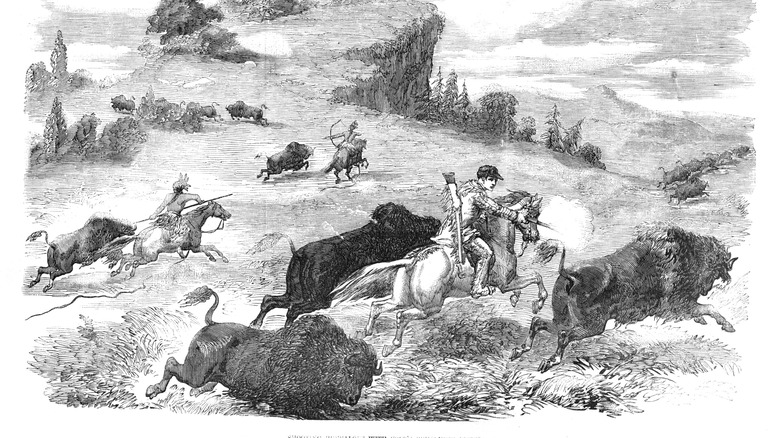

Attacks from American Indians

The reality of the Oregon Trail shows that attacks by American Indians were relatively rare and killed fewer than 400 people during the 1840-1860 period of trail usage. Settlers were more apt to be alarmed by stories than actual encounters with hostile Indigenous people, but the few occasions where it did happen could be brutal. Relations between white pioneers and Indigenous people had become especially poor in the latter half of the 19th century and west of the Rockies, as tribes found their lands and ways of life encroached upon by growing numbers of settlers.

In 1854 Idaho, the Ward massacre saw a 20-person party almost completely decimated by Shoshone — only two young boys were believed to have survived out of the Oregon-bound group. Then, in August 1860, the Utter-Van Ornum group arrived at Fort Hall, Idaho, and was given a U.S. Army escort for about six days. After the escort departed, the group was struck by a 100-strong group of Shoshone and Bannock (and possibly white) attackers that picked them off through the middle of October.

While some waited for rescue near the Owyhee River, four children starved; the survivors resorted to cannibalism. Forty-five days later, only 16 of the 44-person original group survived to be rescued. Four other children were reportedly captured from the Utter-Van Ornum group. Young Reuben Van Ornum was said to have continued to live with the Shoshone after a failed attempt to return to non-native society in 1862.

Wild animals

Pioneers might find themselves facing dangerous animals, such as the wolves and coyotes that inhabited much of the territory in which pioneers traveled, though settlers were more often unnerved by the animals' howling than harmed by them. They might face more danger via venomous snakes, which were known to occasionally kill unfortunate travelers. As diarist Velina Williams related, she had an alarming encounter with a copperhead on one occasion in 1853. As published in the "Transactions of the Oregon Pioneer Association," she wrote, "I found myself standing on a copperhead snake. He was coiled and my foot was across the coil so that the head was fortunately too nearly under my foot to injure me."

Meanwhile, the herds of bison that provided food, fur, and other goods for pioneers and native people alike could prove treacherous. Occasionally, wagon trains were said to be caught in a massive stampede of buffalo. While traveling in 1842 Wyoming, Ezra Meeker and his party were caught in one such nighttime rush. "A roar like an approaching storm could be heard in the distance," he wrote. "How long they were passing we forgot to note; it seemed like an age" (via "The Busy Life of Eight-five Years of Ezra Meeker: Ventures and Adventures"). However, there is little record of anyone killed by buffalo; instead, the huge animals, as well as many other species of the Oregon Trail, had far more cause to fear hunting humans than the other way around.

Weather

Just by looking at the covered wagons used by many travelers on the Oregon Trail, it's clear that pioneers were occasionally seriously vulnerable. Sure, the canvas that arched over their vehicles was typically weatherproofed and offered some protection from the sun and rain, but that could only go so far. Thunderstorms, especially on the great expanse of plains before the Rocky Mountains, could be gut-wrenching, especially if the only cover someone had was the oiled cloth over their wagon that still let in driving rain and howling winds. Pioneers often faced thunderstorms that brought pounding rain, high winds, flashes of lightning, and hailstones that could be large enough to injure unprotected travelers. Nineteenth-century settlements on the Great Plains were known to be occasionally hit by deadly tornadoes as well.

Lightning represented a particular hazard on the wide-open expanse of the plains. As T.M. Barber wrote, traveler John M. Hurd was struck by lightning while crossing the Elkhorn River in 1851 in Nebraska. "He was struck on the right arm," recalled Barber. "Entered his body on right breast and passed entirely through to his ankles, where it passed from him, through his boots, leaving a hole in each boot the size of a picayune. Of course death was instant."