Messed Up Things That Actually Happened On The Oregon Trail

If you're of a certain age, you remember spending hours naming your Oregon Trail family after your own family or friends, guiding their MS-DOS-based adventures, and laughing when brother Stinky Johnny died of dysentery. Hilarity! The real Oregon Trail was filled with about as many accidents and illnesses, and the National Oregon/California Trail Center says more than 300,000 Americans actually did travel along it at the end of the 19th century. From start to finish, it took between five and six months, and it's hard to imagine today. Sell everything that doesn't fit into your wagon, and set out with no guidance from Google Maps? They were a brave bunch, and slightly insane, so it's not surprising a whole lot of messed up stuff happened along the way.

The Utter-Van Ornum Massacre

In truth, there wasn't much conflict between the Native American tribes and early travelers, who were mostly fur traders and missionaries. But once settlers started heading West and claiming land for themselves all willy-nilly, not everyone was pleased. You'd be pretty mad, too.

The ill-fated Utter-Van Ornum wagon train would go down in history with the dubious honor of being the deadliest wagon train (via the Idaho Chapter Oregon-California Trails Association). Led by Elijah Utter (sometimes written "Otter"), the group included four families, 21 children, and a few former soldiers. They were attacked on September 9, 1860, and 11 died in the two-day confrontation. The tale told by the Washington State Historical Society suggests they may have been the fortunate ones, because when the four soldiers took the first opportunity they had to pick the best horses and high-tail their way out of Dodge, they left the party with a broken defense. Colonel George Wright, who was in charge of the military presence and rescue mission, said they likely would have survived if it wasn't for the cowards.

The group scattered, and one of the soldiers made it to a military camp outside Fort Dalles to sound the alarm. The rescue parties stumbled across some stragglers, but the most horrific scene was discovered by a Lieutenant Anderson. He found a camp of 15 people, including five dead who had been partially eaten by the starving living. Once everyone had been accounted for, they found only 15 people survived.

The Sager orphans

Ever feel like you have the worst luck on the planet? You don't have anything on the seven Sager orphans.

According to the National Park Service, six children set off from Missouri with their parents in early 1844, with the seventh being born in the wagon. Patriarch Henry Sager took ill by the time they reached the Rockies, and they buried him alongside Green River. Naomi Sager descended into a sort of grief-stricken illness, and her daughter Catherine wrote she was, "at times perfectly insane." She died near Twin Falls, Idaho, and the children — ranging from 13 years old to a newborn — were orphans for the first time.

They traveled on with the wagon train and ended up in the care of missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. They'd established a safe home in the Walla Walla Valley, and within the year the seven had been officially adopted by the couple ... who were killed in a massacre three years later, along with John and Francisco Sager, the eldest children. The others were taken captive, but only four were ransomed back — the other fell ill and died. Seriously, you don't have it that bad, and if there's one consolation it's the surviving girls' memoirs that talk about the kindness they experienced along the way.

Camp Sacrifice

Emigrants only had what they could carry. Imagine taking your entire family across the country with only what you can pack into a minivan, and no rest stops or Taco Bells along the way. Food was a huge concern, and that makes Fort Laramie — nicknamed "Camp Sacrifice" — that much more tragic.

According to The Plains Across, Fort Laramie became a major trading post. Settlers would keep as much as they could on their overloaded wagons in hopes of trading once they reached the fort, but that wasn't always possible. Everyone was in the same boat, so to speak, and traders didn't have much use for the more impractical items they'd brought along. Accounts tell of the dumping grounds outside the fort, filled with treasured possessions like bookcases and furniture, iron safes, and books. Practical things were left, too, by people needing to spare their oxen from dragging the heavy loads. Anvils, weapons, plows, kegs, and barrels ... all dumped.

Also dumped? Extra foodstuffs, and one account even talked about the 20,000-odd pounds of bacon left behind. Given the starvation that happened later, it's impossible not to wonder how many people died dreaming of everything they dumped.

The Donner Party's undelivered letter

You're probably familiar with the story of the Donner party, the second-most famous thing about the Oregon Trail. They were heading for California, not Oregon (via Online Nevada), when they set off in 1846, and about half met their grisly end in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Whether it's better to eat or be eaten is a discussion for another time, but the tragic footnote is that the entire thing could have been avoided.

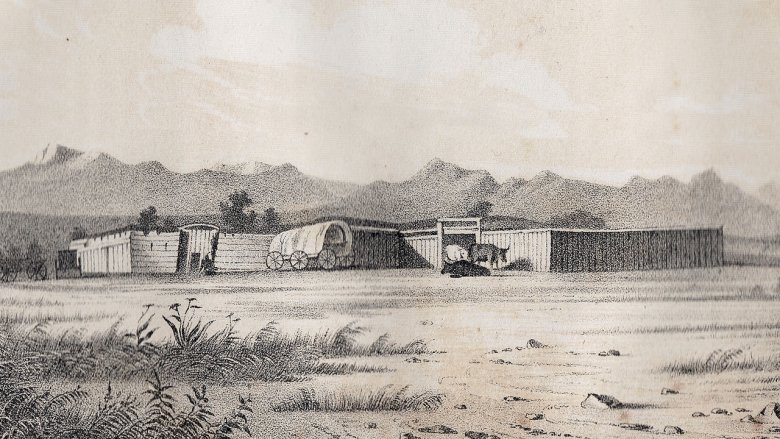

The Hastings Cutoff was a fairly untried shortcut, and Fort Bridger (pictured) sat at the trailhead. There was actually someone riding ahead of the Donner Party acting as a scout, and Edwin Bryant sent a letter back warning them it was too dangerous to take the so-called shortcut. The letter ended up in the hands of Fort Bridger's founders, owners, and the people who stood to gain the most if thousands of settlers started passing through their trading post, so you can probably guess what happened next.

Jim Bridger and partner Louis Vasquez certainly could have handed over the note, sending the Donner Party down the safer route and presumably preventing all the cannibalism nonsense. Instead, they never gave them the warning, sending them to some of the darkest days imaginable, all in the name of making a buck.

Murder or survival?

Surviving the Oregon Trail was just the beginning for some people — just ask Lewis Keseberg. He was a member of the Donner Party, and according to Sierra College, he paid horribly for his survival. Rumors started circulating that he was the first to dig into the not-so-scrumptious meal consisting of his fellow settlers, that he killed others for their meat, and that he preferred human meat to beef. The accusations got so bad he even sued for slander and won $1, but when Keseberg died in 1895, even his obituary reminded everyone he was a cannibal.

He was interviewed a few times, and when he was 62 he issued his first formal statement. Time was supposed to heal all wounds, he wrote, but that was B.S. when it came to something like this. Keseberg had sent his wife and a child on ahead, and said, "For their sakes I must live. ... I can not describe the unutterable repugnance with which I tasted that first mouthful of flesh. ... This food was never otherwise than loathsome, insipid, and disgusting."

He spent two months in the cabin, surrounded by the bodies of his dead friends, with wolves scratching to get to the meat inside. Tamsen Donner left her dead husband and joined him only a short time before she died, too. He swore he only ate and never killed, writing, "A man, before he judges me, should be placed in a similar situation."

Accidental gunshots

The National Park Service calls the Oregon Trail "this nation's longest graveyard." They estimate one in ten travelers didn't survive, and the National Oregon/California Trail Center says the 2,000-mile trail averaged 10 deaths per mile. There was just as much dysentery and cholera as your MS-DOS family faced, but there was another huge problem, too — a lack of gun safety classes. Did you always pick the banker because you'd start with the most money? Good in theory, but how many bankers knew which way to hold a gun?

That's not a joke. Roadtrippers says Blue Mound, Kansas, was the site of the first accidental gun death on the trail, and it happened to the ill-named John Shotwell. He was pulling a gun from the back of his wagon — muzzle first — when it discharged and shot him in the chest. It took him an hour to die, "in full possession of his senses." Sure, there are a lot of ways to go on the trail, but no one wants to be remembered like that (and he definitely wasn't the only one).

The Mormon Handcart tragedies

Hindsight is 20/20, so let's see if you can guess what went wrong with Brigham Young's plan to bring Mormon converts to their new paradise on Earth. The Denver Post reports the plan was simple: British and Scandinavian converts who were too poor to buy wagons would load all their worldly possessions onto a handcart, push them across the U.S., and make the journey in only 60 days. Sounds great, right? You'd totally sign up for that ... until you hear the list of problems.

There were no supply stations, carts broke down better than they rolled, Salt Lake City officials had no idea who was coming, and travelers weren't prepared for doing the work of hunters, pioneers, and oxen all at the same time. Between 1856 and 1860, 10 handcart companies traveled the trail and two — the Martin and Willie companies — suffered heartbreaking tragedies. There were 1,100 people in those two companies alone (via WyoHistory), and they didn't set out until August. Again, hindsight — they were buried under feet of snow, hundreds died, and those who survived lost arms and legs to frostbite.

That's horrible, but there's a fascinating footnote that comes out of all this. Two survivors were 10-year-old Ann Campbell Giles and 12-year-old Maximilian Parker. They lived, met, married, and had a son you probably know of: Butch Cassidy. No wonder he was so badass, just look what his parents went through.

The milk sickness

It's an undeniable fact: the cycle of life doesn't stop for anyone or anything, and there were a surprising number of newborn babies traveling the trail. With so many people dying, that meant a lot of orphans, and babies would typically be passed into the care of, ideally, another nursing mother. It didn't always end well.

Brian Altonen, a medical science and public health expert, took a look at the diseases running rampant through wagon trains and found the heartbreaking case of Susannah, a little girl who died just a month after her mother. Her disease wasn't contagious — no one else caught it from her — but the pioneers didn't know this at the time.

Susannah was passed into the care of a new mother breastfeeding her own child, and Altonen says in order to keep that woman's child away from any possible infection the orphan might be carrying, the caregiver opted to give the baby cow's milk instead of breastfeeding. Unfortunately, the cattle were grazing on plants like poison ivy and white snakeroot, creating deadly and bitter milk. Susannah succumbed to "milk sickness," and while we don't know how many babies died from it, we do know livestock were forced to forage some seriously overgrazed land. They ate all kinds of nasty plants and passed the problems on in their milk. Road to hell and all.

Quack doctors and granny medicine

According to Brian Altonen, the settlers carried were standard medicines like castor oil, rum, peppermint essence, opium, and whiskey, because if you're dying, at least you wouldn't know it. Granny medicine, essentially home remedies passed down from mother to daughter, was common, according to Historic Oregon City. Some things — like using peppermint essence to calm an upset stomach — actually worked (via Fort Morgan Times), but the problem was that it was only the women who knew these remedies. When they died or got sick, the men were left to make things up — like the husband of a Mrs. Knapp. When she came down with cholera, he just gave her a cup of camphor, because that's what you do, right? According to a fellow traveler, it worked.

Plenty of people had the misfortune to listen to one of the quack doctors who hit the trail, too. Edwin Bryant told the tale of a boy who had his leg crushed by a wagon wheel, and it was treated by a quack who tied some linen and a few planks around it. Nine days later, the boy "called to his mother that he could feel worms crawling in his leg," and yes, those were maggots. The boy died as they hacked off the leg with a butcher knife and a handsaw, and it wasn't a happy ending. "The child was dead — his miseries were over!" Bryant wrote. Nice work, doc.

Cholera on an epidemic scale

Cholera is one of those old-timey diseases you definitely don't want, and it was a huge problem for a very gross reason, especially in the floodplain around the Platte River crossing. Let's talk about why, in the least gross way possible.

The river crossing was massively dangerous, and according to WyoHistory, it was made safer but more expensive by the Mormon ferries that were set up in 1847. Even as they started ferrying wagons across, they found they couldn't keep up — dozens of wagons were lined up waiting for their turn to cross. Those who didn't wait tended to drown in full view of others. Talk about incentive. By 1850, the area was swimming with cholera.

There were a few reasons for it, and Brian Altonen says part of the problem was the saline-alkaline waters of the Platte were the perfect breeding ground for cholera left behind in settlers' waste products. Historian Aaron Smith (via Deseret News) notes that the later settlers left, the more susceptible to cholera they would be, mostly because you were following in the footsteps of people who were essentially pooping out cholera as they went. Leave late, and you'd be waiting on the shores of a river where people and animals had been doing their business for months and months, and yes, you were drinking that water, too. You had no idea the decision to ferry or ford the river was so gross, did you?

John Grattan starts a war

Early contact between settlers and Native Americans was relatively peaceful, according to WyoHistory. Tensions continued to mount as more and more people headed West, though, and on August 19, 1854, one hotheaded idiot kick-started a 22-year war.

His name was John Lawrence Grattan, and he was a second lieutenant in the Army stationed at Fort Laramie. At the time, local Sioux were starting to demand more and more in the way of tolls, which makes sense considering the number of people tromping across their land. There were a handful of skirmishes, but the last straw came when a sick cow from a wagon train wandered into a Sioux camp. The people in camp were being starved by a combination of the holdup of promised rations and suddenly needing to share their resources with thousands of extra mouths. They killed and ate the cow, and the officer in charge was actually pretty diplomatic about the whole thing. He offered restitution to both parties, but he sent Grattan to negotiate. Grattan took several howitzers, which is not how you start a peaceful negotiation when tensions are already high.

You can imagine how that went. The Sioux came out on top during that skirmish, and Grattan's body was recovered riddled with arrows. The village head, Conquering Bear, also died, and it only escalated from there.