Groundbreaking Female Filmmakers Of Early Hollywood

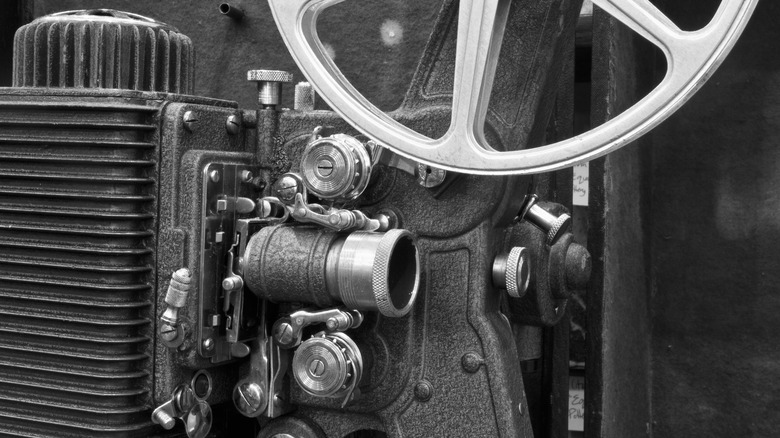

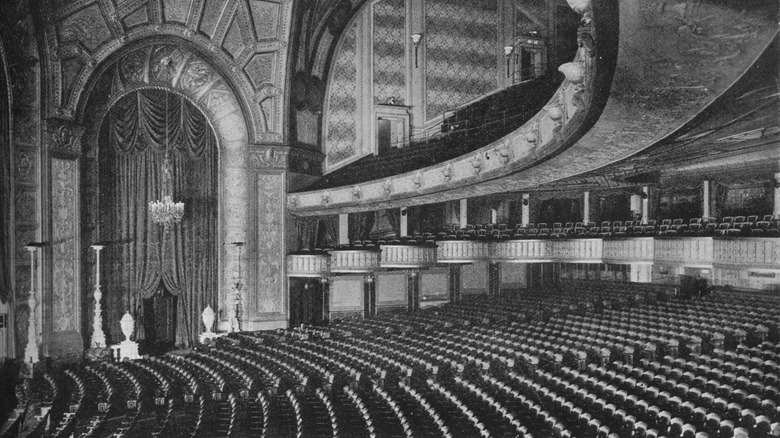

As the 20th century dawned, the beginnings of a film industry that would grow rapidly in the following decades emerged. Following the invention of movie cameras at the end of the 19th century, Hollywood was established in the first few years of the 1900s, per History. With it came glitz, glamor, lights, cameras, action, and impressive talents.

The silent film era of the 1910s and 1920s is often associated with male filmmakers like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, while women like Greta Garbo and Clara Bow emoted silently and beautifully in front of the camera. But several women of this era played behind-the-scenes roles and helped break ground in the film industry, both in Hollywood and in international film scenes. Many of these women have been forgotten or overlooked by history, and many of their films have collected dust in storage for decades, or been lost entirely. Here's a look at the women who were silenced long after the silent film era ended. These are the groundbreaking female filmmakers of early Hollywood and beyond.

French director Alice Guy-Blache has been considered the world's first female filmmaker

Alice Guy-Blache is considered to be the world's first female director, as well as the first director to direct a film with a narrative story, per Britannica. Born in France in 1873, Guy-Blache got her start at age 22 as a secretary for inventor and movie camera manufacturer Léon Gaumont, according to the New York Times. She asked Gaumont if she could film a few scenes, and he agreed. In 1896, she made her first, minute-long short film, "La Fée aux Choux," or "The Cabbage Fairy," in which a woman plucks naked babies out of a cabbage patch.

In 1910, Guy-Blache started her own film company in the United States, which proved to be a massive success, and she opened her own film studio two years later. She ultimately made around 1,000 films, many of them shorts. "I have produced some of the biggest productions ever released by a motion picture company," she told the New York Clipper in 1912 (via the New York Times).

In her later years, Guy-Blache found herself struggling with her health, her finances, her marriage, and her gender. By the 1920s, she was marginalized by the growing film industry as a female filmmaker, and many of her films were lost. "It is a failure; is it a success?" Guy-Blache wrote of her life in her memoirs, which were released posthumously. "I don't know." She died in New Jersey in 1968, aged 94.

Anna Hofman-Uddgren is considered Sweden's first female film director

In 1911, Anna Hofman-Uddgren became the first female film director in Sweden. According to Columbia University's Women Film Pioneers Project, she had already been working on the periphery of Stockholm's movie business for over a decade by that time, introducing and programming moving pictures in Swedish theaters.

In 1900, Hofman-Uddgren married Gustaf Uddgren, a journalist who wrote and co-wrote several scripts for her movies. During 1911 and 1912, she directed six movies, but only one survives: 1912's "Fadren," or "The Father," an adaptation of Swedish playwright August Strindberg's play of the same name. "Fadren" would prove to be the last movie she would direct, because her financier, N.P. Nilsson, died shortly after it opened. After his death, Hofman-Uddgren's only contributions to the film world were as an actor.

Hofman-Uddgren was raised by a single mother, but she was reportedly the biological daughter of the King of Sweden and Norway, Oscar II. According to Prabook, Hofman-Uddgren did not allow the press to mention any details about her personal life. Still, the director alluded to the king in her memoirs, which she began writing in the 1920s. Following her death, four typewritten memoir pages were unearthed, which detailed her first meeting with the king when she was a teenager. Oscar II even financed her studies in Paris, but according to SKBL, he withdrew his funds once he learned she was pursuing a career in the entertainment business.

Elvira Notari is Italy's most prolific film director

Elvira Notari was Italy's first female — and most prolific — film director. According to Columbia University's Women Film Pioneers Project, Notari's career began with the opening of a photo lab in 1905. The lab grew into a family film business that specialized in moving pictures colored by hand. Notari's husband, Nicola, did camerawork, while their son, Eduardo, contributed by acting. Eduardo's teacher often played the femme fatale lead.

Notari's company was named Dora Film, after her youngest daughter. With Notari as its leader, Dora Film became one of the most prominent production houses in Naples, Italy. Eduardo later said in interviews that his mother was nicknamed "The General" for her strong-willed, meticulous leadership skills. She took a realistic approach to filmmaking; instead of artificial tears, for example, she would bring up painful memories from the actors' lives to coax out their real emotions.

In movies such as 1912's "Eroismo di un aviatore a Tripoli," and "Guerra italo-turca tra scugnizzi napoletani," Natori explored topics such as the Libyan War and middle-class Neopolitan life. Many of her movies were inspired by popular Neapolitan songs, per the Australian Film Museum. Over the span of 25 years, Notari made 60 feature-length films and hundreds of shorts. But fascist censorship ultimately contributed to the shuttering of Dora Films, according to the Women Film Pioneers Project.

Lois Weber was a prominent American filmmaker of the silent era

In 1907, Lois Weber and her husband, Phillips Smalley, began working on movies as "The Smalleys," according to Columbia University's Women Film Pioneers Project. In their early years, the Smalleys acted together in moving pictures that were written by Weber and directed jointly. Their 1914 multireel adaptation of Shakespeare's "The Merchant of Venice" was the first American feature directed by a woman.

By 1916, Weber was one of the top directors at Universal, while Smalley appeared to take more of a backseat role in their partnership. In 1917, Weber set up her own company, Lois Weber Productions, and negotiated a deal with Universal that made her the highest-paid director in Hollywood. Weber's pictures were especially notable for their exploration of the social issues of the time. She addressed capital punishment in 1916's "The People vs. John Doe" and contraception in 1916's "Where are My Children?" and 1917's "The Hand That Rocks The Cradle." She once said that she aimed to make movies "that will have an influence for good on the public mind."

Things changed in 1922, when Weber's marriage to Smalley dwindled, along with her film output. In 1928, noting the changes in Hollywood, Weber wrote a newspaper article calling out the disparity of opportunities between genders in the film industry. "Women entering the field now find it practically closed," she wrote (via BBC). "A male beginning would not be so handicapped."

Tressie Souders was the first African American woman to direct a feature film

In 1922, the press named filmmaker Tressie Souders the first African-American female director, according to Columbia University's Women Film Pioneers Project. That year marked the release of "A Woman's Error," a movie that Souders directed, wrote, and produced. The movie was distributed by the Afro-American Film Exhibitors' Company, which was located in Kansas City, Missouri. Billboard magazine described the movie as "the first of its kind to be produced by a young woman of our race, and has been passed on by the critics as a picture true to Negro life" (via the British Film Institute).

The release of "A Woman's Error" coincided with the women's right to vote. It also helped solidify the Kansas City area as an emerging hub for independent Black filmmakers. In addition to Souders, Maria P. Williams was another social activist and filmmaker from the area who was active at that time. She wrote and starred in her own film, "The Flames of Wrath," in 1923. Both movies were lost in time, and little is known about either release.

Dorothy Arzner was the only female director working in Hollywood for a while

Dorothy Arzner grew up in Hollywood, surrounded by the glitz and glamor of the movies, but she originally studied medicine, per the University of California at Los Angeles. After visiting a movie studio and being drawn in, she began typing scripts for a studio that would later become Paramount, according to Columbia University's Women Film Pioneers Project. She then began cutting and editing, ultimately editing 52 movies, including 1922's "Blood and Sand," which she also filmed part of. After being mentored in the movies by director James Cruze, Arzner expanded her portfolio into script writing.

In the late 1920s, Arzner directed four silent films for Paramount, which led her to the opportunity to direct the 1929 sound version of "The Wild Party," starring Clara Bow. "No one gave me trouble because I was a woman," Arzner later said of her work for Paramount. "Men were more helpful than women."

In 1943, Arzner decided to leave Hollywood, due in part to disagreements with MGM co-founder Louis B. Mayer. She went on to work on radio shows and theater productions, taught at UCLA, and shot both Women's Army Corps training videos and Pepsi commercials.

Germaine Dulac was a French journalist-turned-filmmaker

French filmmaker Germaine Dulac was one of the pioneers of the French Impressionist movement in film. In the early 1900s, Dulac lived in Paris and wrote for a feminist magazine called La Fronde, per Women Make Film. The connections she made through journalism, as well as an interest in the magazine's still images, led to her foray into film. After World War I, she started a company called Delia Film with the writer Irene Hillel-Erlanger, kickstarted by funds from Dulac's husband. She began making experimental films around 1915.

In 1917, Dulac joined forces with a theoretician named Louis Delluc, according to Lightcone. Together they began the French avant-garde movement, ushered in by Dulac's movie "La Fete espagnole." Dulac set out to make, as she put it, "the integral film ... a visual symphony made of rhythmic images." Her best-known movie, "The Smiling Madame Beudet" was a groundbreaking example of feminism in film.

Marion E. Wong was a Chinese-American jack-of-all-trades in the film industry

In the early days of Hollywood, Asian representation was generally limited to stereotypical, token roles. But in 1917, a Chinese-American woman named Marion E. Wong blazed a trail by starting the Mandarin Film Company, according to Columbia University's Women Film Pioneers Project. In addition to founding the company and serving as its president, Wong was a costume designer, director, and screenwriter.

The Mandarin Film Company's first feature, 1916's "The Curse of the Quon Gwon: When the Far East Mingles with West," was the first film made entirely by Chinese individuals, both in front of and behind the camera. The movie blended Eastern and Western aesthetic elements in an attempt to expose American audiences to Chinese culture while emphasizing expressions of transnational identity. In 2005, the long-lost film was rediscovered in the basement of San Francisco's Chinese American Historical Society.

For her film "The Curse," Wong cast her family members in supporting roles and played the antagonist herself, in addition to producing, directing, and writing the picture. In 1917, Wong was described in the Oakland Tribune as "energy personified [with] imagination, executive ability, wit and beauty."

Lule Warrenton was an silent movie actress turned silent movie maker

Lule Warrenton entered the movie business during her childhood, when she worked as an actor on stage and screen, per "The Story World and Photodramatist." According to Columbia University's Women Film Pioneers Project, Warrenton started working at Universal in 1913, taking on primarily maternal roles and earning the nickname "Mother" Warrenton. In 1916, she began her own film company under the Universal umbrella, and produced early films such as "The Calling of Lindy" and "The Birds' Christmas Carol." Warrenton was once called "the first and only woman producer with a studio and company all her own." She also served as a writer and director of multiple independent films, including some for children and others that presented social commentary.

Still, within a year of making her first independent film, Warrenton returned to character acting. She ultimately left Hollywood altogether to join the San Diego Conservatory of Music, before returning to the film world. She reportedly began "the first all-woman film company" in San Diego in 1923, alongside fellow filmmakers A.B. Shute, Katherine Chesnaye, and Edith Kendall.

Ida May Park was a prolific silent filmmaker at Universal Studios

In 1916, Ida May Park was working as a scenario writer for the Universal Film Manufacturing Company, according to Columbia University's Women Film Pioneers Project. By then, Park already had over a decade of experience working on stage plays. She wrote 44 films for Universal, half of which were full-length features, over a five-year span between 1914 and 1919. Between 1914 and 1917, her husband, Joseph De Grasse, directed the movies Park wrote. But in 1917, Universal began entrusting her to direct and even edit her own work.

Park and De Grasse left Universal in 1919 for unknown reasons, and Park's directing career was over by 1920. Also in 1920, Park wrote an article for "Careers for Women" in which focused on how the directorial field was "an open field" for "hardy and determined" women. She also wrote that women's "emotional and imaginative faculties gives them a great advantage" (via Encyclopedia.com).

Still, like many of her fellow female directors of the time, Park found that the 1920s film industry was less than welcoming to her gender. Her last known screenplay, 1931's "The Playthings of Hollywood/The Chiselers of Hollywood/Sisters of Hollywood/Gold Diggers of Hollywood," focused on the lack of options for women in Hollywood.

Fatma Begum was the first female director of Indian cinema

Fatma Begum was the first female director and production company owner in India, per Republic World. Initially trained in theater, Begum began her career by staging Urdu plays before entering the Indian film industry in the early 20th century, according to Feminism India. When she entered the film world, it was so dominated by men that male actors would even play female roles on stage and screen. Begum began as an actor, making her film debut as the female lead in the 1922 silent film "Veer Abhimanyu."

In 1926, Begum made her directorial debut with the film "Bulbul-e-Paristan," which was the first Indian film to be directed by a woman. She went on to direct several other films over the next decade or so, including 1927's "Goddess of Love" and 1929's "Goddess of Luck." Still, "Bulbul-e-Paristan" remained her most famous film — due in part to its groundbreaking director, but also due to its big budget and advanced special effects.

Soon enough, Begum became the first Indian woman to open her own production company, Fatma Films. Her last film is thought to be "Duniya Kya Kahegi," released in 1937, according to Cinestaan. In 1931, Begum's daughter, Zubeida, followed her mother's groundbreaking lead by becoming the first Indian female actor to star in a talking film, "Alam Ara."

Dorothy Davenport made movies with a message

In 1911, the Nestor Film Company moved west to southern California, and so did an actor named Dorothy Davenport, according to Columbia University's Women Film Pioneers Project. Davenport was a prominent and prolific actor at the company when it was absorbed by Universal shortly thereafter. The time was also ripe in the industry, as feature-length films were emerging, per Silent Film. But tragedy soon struck Davenport's personal life as her husband, screen star Wallace Reid, became addicted to painkillers and subsequently died in 1923.

That same year, Davenport worked on a movie called "Human Wreckage," which tackled narcotics addiction and in which she played a drug addict's wife. She used the film's profits to open the Wallace Reid Foundation Sanitarium and her own independent production unit. "Human Wreckage" would be the first of a string of films with social messages that Davenport was connected to, but historians remain unsure of the extent of her role in their making, as she neither wrote nor directed them.

In 1929, Davenport got her first director credit with the movie "Linda," which depicted a woman sacrificing her education and mental health for men. She also co-directed 1934's "A Road To Ruin," which notably included a dramatic back-alley abortion scene. While Davenport's role behind the scenes of her own movies remains somewhat mysterious, her role in pushing certain social messages and helping to shape the 1920s film industry is clear.