The Craziest Stunts And Camera Tricks From Silent Movies

"There is nothing new under the sun," Ecclesiastes says. Everything created harkens back to what came before, for inspiration, for the language of the medium in which the work is made. And this is certainly true for cinema — everything that is made today, from avant garde indie projects to crowd-pleasing blockbusters, owes a debt to the filmmakers working in the silent era, the early days of film technology.

The primitive technology of early 20th century cinema is perhaps easily overlooked — instead of a soundtrack that existed as part of the film, cinema audiences would be treated to live musical accompaniment to the latest releases from movie studios. Movies would arrive at the cinema in reels with no more than a 15-minute run time, before they had to be changed manually by a projectionist. Film itself was in its infancy, the footage often grainy, with performers having to overact and don extravagant makeup to portray the thrust of the narrative through what was, at the time, a primitive medium.

No sound. No color. No CGI. But what did exist in droves back in the first decades of commercial cinema was ingenuity, ambition, and a very real desire to entertain. As such, the silent era of film contains some of the most innovative, ballsy, and downright jaw-dropping moments that still have the wow-factor associated with good movies even today, 100 years down the line, and which continue to inspire today's most boundary-pushing filmmakers. Here are just a few that are worth revisiting.

Buster Keaton survives a house falling on him

Joseph "Buster" Keaton accomplished a great many feats over a long and highly influential career. Known by his nickname "The Great Stone Face" for the deadpan expression he maintained in the face of chaos, Keaton's was arguably "the greatest actor-director in the history of the movies," according to Roger Ebert.

But Keaton's prowess was in his physicality. As a child, Buster would perform a live act with his vaudevillian parents, in which he was hurled across the stage like a ragdoll, per The Oldie. When he finally made it to Hollywood as a young man, Keaton transitioned his slapstick effortlessly to the silver screen.

Ebert claims, "no silent star did more dangerous stunts than Buster Keaton. Instead of using doubles, he himself doubled for some of his actors, doing their stunts as well as his own." Automobile crashes, explosions, brawls, and chases were all regular fixtures of Keaton film reels, with the rubber-bodied performer seeming to take every hit that the script threw at him.

However, Keaton's most famous stunt, from 1928's Steamboat Bill Jr., required him to stand absolutely stock-still, as the wall of a house crashes down upon him, while Keaton is saved by being stood in just the right spot to pass through the window. The stunt required exceptional nerves and an element of insanity, as Keaton himself later remarked. "I was mad at the time, or I would never have done the thing," per the American Film Institute.

Harold Lloyd's high rise trickery

Safety Last! stars Harold Lloyd — considered alongside Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin to be one of the premier on-screen comedians of the silent era — as a cash-strapped young man trying to make it big in New York, where, in the 1923 film's most famous scene, he attempts to climb the face of a 12-story building as a promotional stunt for a department store, for a fee of $500. The climax comes when Lloyd, after being lifted unexpectedly from a ledge by an opened window, finds himself hanging from the hands of the building's clock face, which then begins to tip out of its fixtures. Today, it is considered one of the defining scenes of the era and has been parodied in countless films, such as Back to the Future and Martin Scorsese's Hugo.

The escalating danger — comedic though it is — still has the power to get an audience's adrenaline pumping. However, the stunt isn't quite as dangerous as it at first appears. Though Lloyd is indeed hanging from the building himself, there is actually a ledge just a few feet below him off screen, instead of the sheer drop suggested by the editing, as Silent Locations explains.

However, Lloyd's hi-rise exploits are even more impressive once you realize that he is hanging and climbing more or less one-handed — per Vanity Fair, Lloyd was missing a good portion of his left hand after a prop exploded in a studio in 1919.

Charlie Chaplin skates close to the edge (1936)

Completing the trifecta of classic silent comedians is Charlie Chaplin, whose bowler-hatted Little Tramp character is one of the most beloved icons of world cinema. Chaplin's movies are notable not just for the exuberance of his on-screen personas but also the high degree of cinematic innovation involved in the production of his greatest films. Among these is the 1936 film, Modern Times, in which the Little Tramp takes a job as a night watchman in a large department store, which he freely roams with his love interest, Ellen.

It is here that Chaplin appears to perform one of his greatest stunts. Keen to show off in front of Ellen, the Little Tramp straps himself into a pair of roller skates, then skates backwards, unbeknownst to him, right to the edge of a third-floor balcony with no railings (a sign with the word "DANGER" is in view throughout the scene). "Look! I can do it blindfolded!" reads a title card, before the Tramp, still unaware of the drop, begins to skate circles, sightless, one leg dangling right over the lip of the balcony.

However, not all is as it first appears — the void into which Chaplin is apparently just inches away from falling is in fact a matte-painting stood close in front of the camera, obscuring a solid floor behind, as shown by recent mock-ups (via YouTube). The scene offers an early example of visual effects that still to this day looks entirely convincing.

Swashbuckling Fairbanks

On-screen swashbuckling has always drawn an audience, and back in the days of silent film, cinema goers were no different. As such, early cinematic all-action heroes such as Douglas Fairbanks, who became known as the King of Hollywood per PBS, were huge stars.

Originally a comic actor in the mode of Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Charlie Chaplin, in the 1920s Fairbanks starred in a string of high-production costume adventure films, starting with the hugely successful The Mark of Zorro in 1920 and culminating in 1926 with the lavish The Black Pirate, a production involving five "fighting sets," full-scale galleons, and 70,000-gallon tanks of water, according to the website of the San Francisco Silent Film Festival.

In one high action fight scene, Fairbanks is shown descending the sail of a ship with a knife, plunging it into the material and dropping slowly as the blade splits the canvas. The stunt has been homaged in countless pirate adventures over the years, but though Fairbanks was noted as a highly athletic and capable stunt performer, his feat was aided by the use of a clever pulley system, according to silent film expert Tracey Goessel, while the sail was set at an angle of 45 degrees to achieve the impressive shot.

The mechanics of using a knife to slide down a ship's sail in the manner portrayed was tested on the show Mythbusters in 2007, but their experiments concluded that such a stunt couldn't be achieved in reality.

The cityscape of Metropolis

It is impossible to overstate the importance of Fritz Lang's silent masterpiece, 1927's Metropolis, in creating the blueprint for how science fiction has looked on screen for almost a century. Inspired by German Expressionism and Art Nouveau, as well as the burgeoning Bauhaus movement according to Artland, the film captured the essence of early 20th century European art and design and distilled it perfectly into the language of cinema. One could point to the still-haunting robot — or "Maschinemensch" — design, and the special effects used to accompany the robot's transformation into female form, as Metropolis' most memorable image. But really, it is the metropolis itself which is the star of the show, the depiction of which is the film's truly greatest innovation.

Before the era of film noir, Lang ingeniously employed the use of shadow to create the film's foreboding atmosphere and a sense of enormous scale, turning model buildings into an imposing future cityscape. As noted by Artland, the magnitude of the city was increased with the use of the "Schüfftan process," a cutting-edge mirror technique that showed the film's multitude of extras appear tiny among the metropolis' towering skyscrapers. Star Wars, Bladerunner, and countless other classic movies owe a debt to those masterful innovations pioneered during the silent age of cinema.

A Trip to the Moon (1902)

But it was earlier still that the possibilities of film were first demonstrated in the work of visionary filmmakers working at the turn of the century, such as the French director George Méliès. Born in 1861, Méliès spent the early part of his career as a magician and illusionist, according to Britannica, the fundamentals of which he was later to bring to his films, developing some of the world's earliest cinematic special effects in the process.

As well as pioneering such tricks as double exposure and stop motion — both of which have remained common effects to the present day — Méliès was one of the first filmmakers to employ costume, make-up, and set design to draw viewers into movie narratives, and was one of the earliest directors to use film to tell fictional stories as entertainment.

The greatest of all Méliès' films — he produced more than 500 shorts in his lifetime, according to Filmsite – is undoubtedly Le Voyage dans la lune, or A Trip to the Moon, a 14-minute science fiction short telling the story of a professor's journey to the moon, which, in the film, has a haunting human face. The most famous moment of the 1902 film depicts the professor's rocket crashing into the moon's eye, but the entire work is gilded with eye-popping effects and luscious sets that, though they may have a certain homespun charm, retain their magic.

Parting the Red Sea

It takes great ingenuity to film a convincing miracle CGI, but as has already been seen, the filmmakers of the silent era had plenty of that.

The producer Cecil B. DeMille had made his name in Hollywood with a series of morality tales about love, lust, and marriage, according to Patheos, before a competition amongst cinema goers asked entrants to suggest the subject of DeMille's next project. "If you break the Ten Commandments — they will break you" was the entry that DeMille found the most compelling, and the producer, deciding to take the literal route, began work on a biblical epic, which would become 1923's The Ten Commandments.

According to the Chicago Film Society, DeMille employed a grand total of six cinematographers to bring to life his vision for the story of Moses and the Israelites, which would eventually become a monumental work spanning a four-hour running time. DeMille believed that The Ten Commandments would be "the biggest picture ever made, not only from the standpoint of spectacle but from the standpoint of humanness, dramatic power, and the great good it will do."

Much of the film's success comes from its staging of Biblical miracles, chief among them Moses' parting of the Red Sea and the crossing of the Israelites, which was achieved with the use of reverse film, double exposure, and the use of two 5-foot gelatin moulds, according to The Solomon Society.

Billy Bevan destroys a fleet of cars

As with cinema audiences today, the filmgoers of the silent age also had an appetite for destruction, though they were more likely to find mayhem in comedic shorts as they were in adventure flicks and epics, where it would often be deployed as a visually satisfying punchline or payoff.

Billy Bevan was an Australian-born performer who began his film career in the 1910s, after arriving in America as a traveling opera performer, according to Central New South Wales Museums. His took the starring role in a number of hit comedies, in which he "worked for his laughs and worked hard," according to film historian Kalton C. Lahue. "He was a dumpy little fellow full of self-assurance, his bush moustache being his greatest asset."

In 1925's Super-Hooper-Dyne Lizzies, Bevan plays the hapless assistant of a professor attempting to develop a car that runs on radio waves, who, when pushing the prototype down the street, manages to accumulate five other cars in line, which he then accidentally pushes over a cliff (bar the prototype, of course). Visually impressive — some trickery is used to make it appear the heavy-set Bevan is able to push five cars uphill — the piling up of the falling cars is as cathartically satisfying as it is humorous.

Buster Keaton clears the tracks

It would be impossible to compile a list such as this with just a single Buster Keaton stunt — indeed, it would be possible to make one of just Keaton's greatest moments alone.

The General, released in 1927, contains much of Keaton's best work and was described as a "masterpiece" by the influential critic and lifelong Keaton fanatic Roger Ebert. It is the story of, as Ebert describes it, "a Southern railway engineer who has 'only two loves in his life' — his locomotive and the beautiful Annabelle Lee." The train on which Keaton's character is the engineer is stolen on the eve of the American Civil War, leading to a chaotic train chase — achieved through unexpected comic diversions (otherwise how could one train not just follow another?) — and Keaton performing unexpected stunts involving both the trains and the tracks.

"In films that combined comedy with extraordinary physical risks, Buster Keaton played a brave spirit who took the universe on its own terms, and gave no quarter," Ebert claims in another article, and nowhere is this more noticeable than the scene in which Keaton, sat stop the train's cowcatcher, dislodges errant railway sleepers to keep his engine going full steam ahead — and nearly hits himself in the head with one in the process.

The most expensive silent stunt ever

Chaos and comedy were two sides of the same coin in the silent age of cinema, when bigger and bigger stunts were employed to elicit bigger and bigger laughs. As such, let's stay with Keaton's The General, which Roger Ebert calls "an epic of silent comedy," for what Film Stories claims to be "the most expensive silent movie stunt of all time."

Keaton, as director as well as performer, was given a budget of $750,000 ($11 million in 2020) to film The General, per Film Stories, with a huge proportion of that cash going on the 1927 film's climax — a train traveling across a burning bridge, which then collapses into a river. On paper, it sounds akin to the Billy Bevan's Super-Hooper-Dyne Lizzies, but the stakes for The General were so much higher. As Film Stories explains, there was no budget to replace either the train or the bridge, so Keaton had to have a total of six cameras — hand-cranked, as they were back then — to capture a good enough shot for the movie.

Thankfully, it looks fantastic. Hugely dramatic, and, somehow, knowing there is no CGI at work, it remains jaw-dropping today.

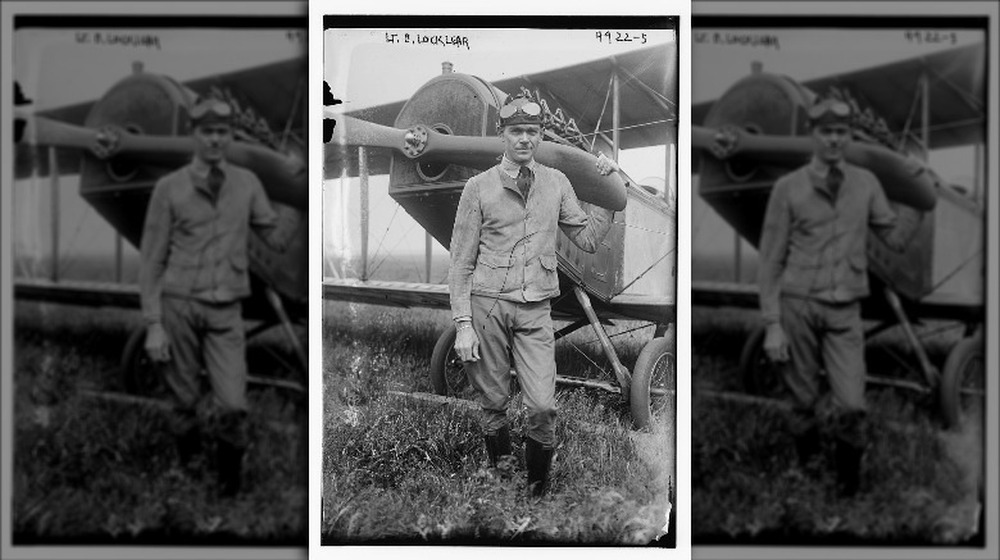

The lost films of Ormer Locklear

Today, Hollywood stunt performers are protected by rigorous training regimes, as well as health and safety legislation to ensure a high degree of personal safety. In the age of silent film, however, such checks and balances were yet to be put in place — with tragic consequences.

Ormer Locklear was one of the silent era's most famous stunt pilots. Originally a pilot in the United Army Air Service in World War I, he invented the "wing walk," which was, according to The Portal To Texas History, a dangerous feat accomplished in the course of fixing one of the aircraft's radiators. Later, he was a stunt pilot in a "flying circus." Locklear became a superstar daredevil after starring in The Great Air Robbery, a vehicle to demonstrate Locklear's flying talents that became a huge commercial success in 1919.

However, during the final day of filming the follow-up, 1920's The Skywayman, Locklear "was supposed to simulate his aircraft crashing into the ground during nighttime shooting," according to Eugene McDermott Library at the University of Texas. "As Locklear entered the dive he was either blinded and disoriented by the landing lights, or the lights were not turned off in time for him to successfully pull out of the dive."

Locklear, who was just 28 at the time, was killed, along with his co-pilot, Milton Elliot, while both The Great Air Robbery and The Skywayman are believed to have been lost.