What Victorian Halloween Was Really Like

What's a Halloween season without at least one ghost story set in the fogbound, gaslit streets of Victorian London? The aesthetics of the period have made a considerable impact on the iconography of Halloween and the horror genre, from Inverness cloaks and ladies' walking suits to Gothic Revival architecture. Gothic fiction, too, has left its mark, with many of its most influential works (see "Dracula" by Bram Stoker) written in the Victorian era (via TheCollector), and Halloween seems the ideal time of the year to check out a story or two, per Bustle.

The holiday itself shows some influence from the clashing cultural currents from that time; or, at least, modern perceptions of them. For example, as History Today points out, the Victorians weren't as sexually repressed as they're often depicted, but tensions between outward prudery and morality and repressed dark urges, whether real or imagined, inform much of horror fiction — and more than a few Halloween costume ideas.

With how much of an impact the trappings of 19th-century England have had on our modern Halloween, it's worth wondering — as the Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation did — what their own celebrations were really like. One might imagine a Victorian as the epitome of Gothic melancholia, or perhaps a euphoric one-night release of taboo fears and desires. But the evidence suggests that the Victorians marked Halloween in ways not too different from ours: with themed parties, games, and treats. The general character of the holiday was still evolving at the time, of course, so there was plenty to distinguish the holiday in their hands. Here is what Victorian Halloween was really like.

Halloween started getting popular again in the Victorian age

It isn't a direct evolutionary line between the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain and modern-day Halloween, but Samhain does seem to be the most significant base element of today's holiday. Considered the beginning of the dark half of the year, Samhain was thought to be when the veil between the worlds of the living and the dead was at its weakest. Per Britannica, the Celts marked the festival with bonfires and disguises, partly in celebration and partly to ward off malign supernatural forces.

Samhain's date eventually coincided with the Catholic All Saints' Day, moved from May 13 to November 1 at some point in the eighth century (per Britannica). The hallowed night before All Saints became known as All Hallows' Eve, or Halloween, and the Christian holy day and Celtic festival coalesced by the end of the Middle Ages in the British Isles. But the religious element of Halloween was stamped out during the Reformation, and stricter religious sects limited any celebrations in the British colonies in America.

In America, puritanical hostility to religious holidays was tempered by secular harvest festivals every autumn, gradually incorporating Native American customs and elements of Halloween (per History). Back in Britain, the rapid advance of industrialization and science created a hunger for a romanticized past by the 1800s, and Halloween's rural and folkloric elements helped grow its popularity among the Victorians, according to Halloween historian Lesley Bannatyne.

The Scots and Irish spread Halloween in America

Modern Evangelical groups make the odd headline for decrying Halloween as Satanic, but in colonial America, the Puritans railed against it for being too Catholic, according to the Montgomery Advertiser. The urge to celebrate during the harvest season couldn't be wholly eliminated, but colonial autumnal festivals were not Halloween as such. Per History, it was most often observed in the South and least often in New England. The fall celebrations held in Halloween's place gradually blended customs from various European groups with traditions from Native American tribes. Divination, song and dance, pranks, and ghost stories were widespread elements.

The Victorian era saw mass emigration from Scotland and especially Ireland to America, and it was with the mass influx of Scots and Irish that Halloween became a nationally celebrated holiday in the United States. Halloween historian Lesley Bannatyne notes its Catholic — and Irish — roots were seen as embarrassing to members of the upper crust, who preferred to think of it as an Episcopalian and North English import. But even with these prejudices, Halloween won a presence for itself among American society by the 1870s.

The American melting pot continued to shape the character of Halloween, even after its popularity boost via the Irish diaspora. According to Bannatyne, some of the other customs and folklore that influenced the holiday's practices include German beliefs in witchcraft, African fears of black cats, and Dutch fondness for masked parties.

Queen Victoria threw her own Halloween parties

The woman whose name has become synonymous with a humorless, inflexible, and priggish manner was anything but for most of her life. The BBC's History Extra noted across two articles Queen Victoria's healthy appetite for food, sex, and humor. It seems she also liked a good party, and found Halloween an ideal time to throw one. According to the Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation, it was a short-lived tradition to have a lavish and riotous Halloween night celebration at Balmoral Castle, with the queen herself presiding over the whole affair.

In "Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween," David J. Skal quotes from contemporary reports describing preparations for Victoria's Halloween, which took days. The party was open to the neighboring farmers as well as honored guests. Some attendees held onto scraps all year round to use in the party's central attraction: a massive bonfire used to roast an effigy of a witch (or, in some years, someone in the queen's bad graces).

Victoria and her daughter Beatrice led a procession to the fire by open carriage, and when it was at full blaze, servants dressed as goblins and fairies brought in the witch for burning. Then came the dancing, all to the music of the queen's own piper; per historian and researcher Mimi Matthews, the crowds were too elevated for an indoor ball, so the dance was held around the bonfire.

Halloween was a night for love

Modern-day Halloween offers opportunities for youthful abandon and risqué attire, but it isn't often thought of as a time for romance. It wouldn't have been considered so in its earliest days either. The precursor festival of Samhain (per Britannica) was concerned with the end of summer, celebrating the harvest, and navigating a dangerous and liminal time in relation to the spirit world. The weakened boundary between the living and the dead also made Samhain, and later Halloween, an ideal time to practice divination.

By the Victorian era, such sober attempts to see the future during Halloween had become popular parlor games, and it was fashionable to use them in seeking a spouse. According to David J. Skal's "Death Makes a Holiday: The Cultural History of Halloween," fortune-telling in the name of love became so popular among the Victorians that it almost entirely supplanted belief in the dead haunting the living or supernatural creatures making mischief.

To catch a glimpse of their future weddings, young people played a variety of games. Nuts were thrown into fires, and the way the nut reacted indicated the temperament of the thrower's marriage-to-be. Girls sliced apples while looking into a mirror, expecting a glimpse of their future husbands to appear behind them once they'd finished eating. Per the Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation, a riskier game was baking a cake full of objects. While rings meant wedding bells, a needle meant spinsterhood — or a very difficult piece of cake to swallow.

Party games trumped tricks-or-treats

The best part of Halloween for many a child is trick-or-treating. Who didn't look forward to getting heaps of tooth-rotting goodies from the neighbors? But the phrase "trick-or-treat" is less than a century old, according to the History Channel's "The Origin of Halloween" (via YouTube). The medieval practice of All Saints' Day saw the poor or children begging for "soul cakes" door to door on Halloween night in exchange for prayers to release departed loved ones from purgatory. But the modern practice of trick-or-treating got started in America as a way to buy off particularly destructive pranksters.

In Victorian England and America, handing out treats wasn't as central to Halloween as parties, and a key part of any Halloween party was the games. Author and researcher Mimi Matthews notes that many of the most popular games had at least some connection to medieval or pre-Christian beliefs, though other historians of Halloween (via I Skull Halloween) say that customs the Victorians regarded as pagan were actually closeted and half-forgotten Catholicism. Either way, party games that were deemed unacceptable the rest of the year were broken out on Halloween.

Divination games were always a hit, played with food, mirrors, melted lead, or bowls and blindfolds. Bobbing for apples was popular before, during, and after the Victorian era. There were rather dangerous games with fire, too. And per "Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween," darker games in Ireland, Scotland, and Wales were thought to predict death.

Halloween treats usually weren't candy

Should any trick-or-treaters happen upon a time slip this Halloween and find themselves knocking on a Victorian door, they probably won't be greeted with candy. Handing out sweets wasn't common practice then, and store-bought, pre-wrapped, sugar-filled treats are a recent addition to the holiday, coming even after the phrase "trick-or-treat," according to the History Channel's "The Origins of Halloween" (via YouTube). But if our time-traveling tykes were invited to a Victorian Halloween party, they wouldn't leave empty-handed.

Before candy, nuts were the prime All Hallows' Eve treat. According to author Mimi Matthews, they were such a staple of the evening that, in northern England, Halloween was also known as Nutcrack Night. Nuts were usually enjoyed roasted, and the roasting itself featured heavily in some Halloween games. Fruit was another popular treat; glazed apples could be found over the fire along with the nuts. There were baked goods, too, like the Halloween dumb cake, which needed careful rituals maintained around its baking to ensure its fortune-telling power. And it was common to wash all this down with a good ale.

More elaborate parties would go further than cakes and nuts. Surviving magazines from the period hold suggestions for entire Halloween menus. Ingalls' Home and Art Magazine (via Matthews) listed some sweet treats we might eat today, like chocolate creams or walnut ice cream. But Ingalls' also called for baked oysters and tongue salad, which some trick-or-treaters today might turn their noses up at.

Costumes were homemade, themed, and not exclusive

Today, Halloween is the time of the year for a costume party, and when it comes to the theme of the costume, anything goes. But masking was once much more popular as a year-round activity. As recently as the early 20th century, according to History, Easter, New Years, and Valentine's Day could be an occasion for a costume party just as easily as Halloween, and masquerades were common. The Victorian era may have been when masking became a major component of Halloween; according to author David J. Skal, there is scant hard evidence for costumed revelry on Halloween night until the late 1800s.

Whenever they became associated with the holiday, Halloween costume parties were common by the end of the Victorian era. The costumes themselves weren't quite what we would expect to see today. Aside from paper masks, there were no costumes widely available in stores; a Halloween disguise was a homemade effort. It was rare to see a costume patterned after a particular figure from pop culture in the Victorian period, too. The specificity of character was trumped by fitting a set theme.

Popular themes for Halloween costume parties included subjects we still associate with the holiday today, such as ghosts, black cats, the moon, and the earliest haunted house attractions. But according to Halloween historian Lesley Bannatyne, fairy tales and nursery rhymes were also common themes.

jack-o'-lanterns were used as party invitations

As Halloween's popularity grew, Halloween parties became a notable date on the Victorian social calendar. Per the Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation, it was a sign of standing to be invited to a well-to-do party on All Hallows' Eve. For the lucky guests, the invitation itself might not come through the post or a direct question. Instead, it might come tied to a jack-o'-lantern left on the doorstep.

The jack-o'-lantern used might or might not be a pumpkin; it would depend on which side of the Atlantic the party was. The practice of carving vegetables into lanterns with frightening faces goes back to the Celtic Samhain, according to National Geographic, and may have initially served as representations of slain and beheaded enemies. But in Ireland, the vegetable used varied, with beets, potatoes, and turnips all popular choices. The turnip gradually took precedence, and jack-o'-lanterns were also known as ghost turnips in the late Victorian period.

Turnips still saw regular use as jack-o'-lanterns into the 20th century, but as Irish and Scottish immigrants came into the United States during the 1800s, they found that pumpkins — not native to Ireland — were more plentiful in America. They were also easier to carve and light than root vegetables. The pumpkin got a huge boost in its popularity as a Halloween symbol in the Victorian age thanks to a reprinting of Washington Irving's "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow."

The British accused the Americans of getting carried away

It may be that some of our modern assumptions about the Victorians (e.g., their sexual repression and uptight sense of morality) comes down to a misunderstanding of their sense of humor. In 1843, according to History Today, a British magazine mocked the allegedly puritanical excesses of the Americans by facetiously claiming that standards were so strict that even piano legs needed stockings. A few years later, a French magazine told the same joke about the British, and this time, observers and later generations took it at face value. The myth about Victorians hiding their piano legs for shame persists to this day.

But Victorian Britain didn't cease its mockery of her former colonies with the piano legs joke. America was often pilloried in the British press, if not for stuffiness than for mischief and rough-housing. In "Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween," David J. Skal suggests this might have applied to views on American Halloween, too. There, the holiday was shaped by waves of immigrants with their own related customs, from the German Fasnacht carnival to French memories of the Feast of Fools from the Middle Ages. Why wouldn't it be rowdy?

As it happens, Victorian Britain was often as wrong about America as modern thinking is about the Victorians. Halloween in America during the 1800s was not unlike the Halloween described in contemporary British reports (via Mimi Matthews). Americans, too, favored games, divination, and private, respectable parties.

The rise of ghost stories helped bring back the frightful side of Halloween

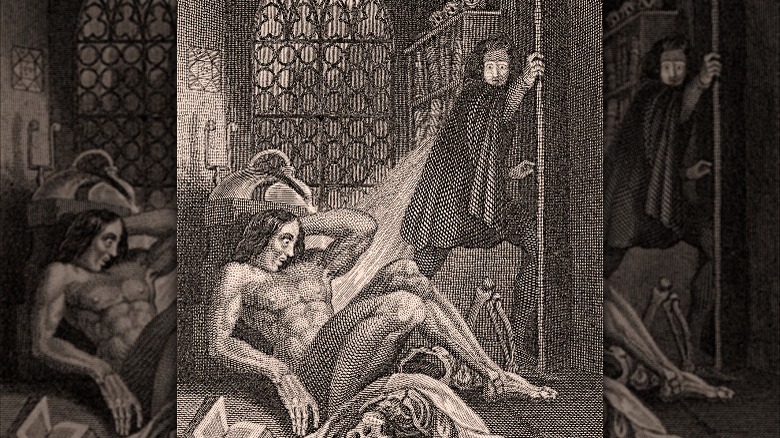

In "Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween," historian David J. Skal wrote that the Victorian era was when ghost stories reached the peak of popularity. In part, Skal attributed this to the advance of science during that period, which seemed to support philosophical materialism and make the afterlife less credible. This in turn fueled the rise of practices like spiritualism, alleged communications with the dead that attracted interest from notable scientists of the day, according to The New Yorker.

It was these currents in the cultural air, combined with the ease of printing in the wake of industrialization, that made ghost stories so popular among the Victorians, though they were associated more with Christmas than Halloween at the time (per The Guardian). The latter holiday, while retaining loose ties to ancient associations with the dead and spirits, was more for party fun and matchmaking, as the Gaslamp Quarter Historical Foundation explains. But alongside ghost stories, the Victorians pushed the genre of Gothic literature, and in time, such stories would have a marked impact on the horror fiction currently celebrated every Halloween (per National University).