What Is A Cabinet Of Curiosities?

A cabinet of curiosities is just like what it sounds like: a collection of weird and wonderful objects displayed in one place. These unusual collections date back to the Italian Renaissance, when human beings were becoming more interested in natural history, per Britannica. More than 250 of these unique collections were documented in Italy in the 16th century, and they included whatever the owner believed to be interesting. Collections ranged from herbs to manuscripts to more obscure items like preserved animals (via Sotheby's Institute of Art).

Known as a Wunderkammer, or a "wonder chamber," the word first appeared in a book that chronicled the lineage of the noble German Zimmern family, according to Artsy. Around the same time, the word also appeared in a book by Samuel Van Quiccheberg, adviser to the Duke of Bavaria. The book is considered to be the first of its kind detailing how to collect and display almost everything (via Britannica). Collections could be vast, filling up an entire room, or small, fitting in a single drawer or on a shelf, according to Sotheby's. But they all had one thing in common: a desire to capture the imagination of the viewer.

Cabinets of curiosities often told stories

The Renaissance was a time of enlightenment following the Dark Ages, and it resulted in a thirst for new knowledge (via History). This longing caused many people to look for and gather thought-provoking items. These collections were initially in vogue among the aristocracy, and Sotheby's Institute of Art reports that while rare objects were displayed to impress friends and guests, they were most often used to define "intelligence, erudition, wealth, and taste."

According to Daily Art Magazine, there were four primary categories of collections: naturalia, artificialia, exotica, and scientifica. Items in earliest known cabinets were often a blend of science, theology, and imagination that would reflect the owner's philosophy, according to The Collector. The British Library explains that some collections would contain artifacts that often told a story or presented a particular theme. The size of any given collection was certainly impressive, but sometimes, specific objects were the real storytellers.

Relics didn't have to be real

Some relics were mysterious and beguiling, and the stories attached to some of them stretched the truth. For instance, a supposed "mermaid" was actually constructed using the torso of a monkey and the tail of a fish (via Sotheby's). But the absurdity of the object often didn't matter as much as the spectacle itself. These curios were seen more as a representation of how the owner interpreted the world.

These kinds of anomalies might seem odd to us in a modern world with information at our fingertips, but hundreds of years ago, they were a glimpse of a massive world of mystery and "endless beginnings," according to historian Earle Havens (via Artsy). Apothecary Ferrante Imperato was the first to illustrate his wonder room. His 1599 book "Dell' Historia Naturale" catalogs some 35,000 specimens from his collection, which included fish on the walls, birds on shelves, and an alligator attached to the ceiling surrounded by shells and other items.

Sunflower clocks, ghosts, and giant humans

Because there were no rules about what one could house in a cabinet of curiosity, one's imagination truly was the limit. For instance, the cabinet of curiosities of Rudolf II, housed in a castle in Prague in the 17th century, was known as one of the largest collections of its time. It contained mechanical objects, like a crystal clock with moving parts, and animal specimens ranging from birds to crocodiles, per the World of the Habsburgs.

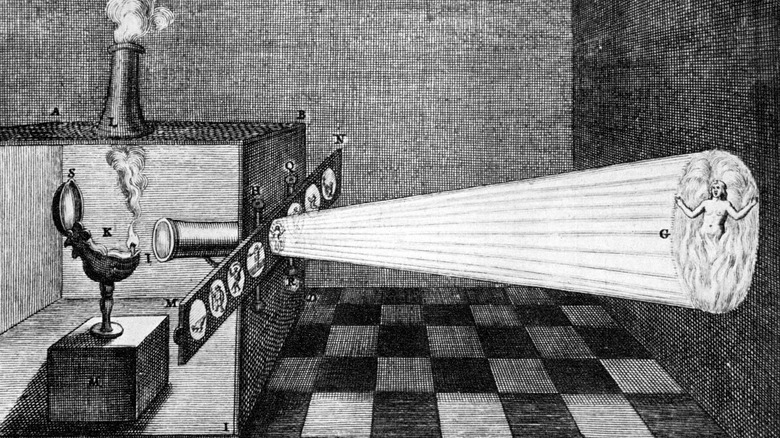

During the same century, Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit scholar, collected oddities that included many of his own inventions. One such creation was a sunflower clock that supposedly ran on the properties of a sunflower seed floating in water. Other curiosities included a series of mirrors in which ghosts would appear, bones from a supposed race of giant humans, and an organ that played every birdsong (via Biodiversity Heritage Library).

Other collections were more bizarre

Different interests undoubtedly sparked collections that might have been a little more bizarre than others. Anatomist Frederick Ruysch's cabinet of curiosities was just such an example. Kept in several small houses, Ruysch displayed preserved fetuses and babies, which were injected with chemicals that made them flexible. One of his more eerie objects was a gecko holding a human fetus in its mouth (via Arizona State University's Embryo Project Encyclopedia). Ruysch took special care in presenting some of the more grotesque items by covering unappealing sections with jewels and fabrics. The British Library explains that his daughter even made collars and necklaces for some of his displays.

Ole Worm, a well-known collector from Scandinavia, had a cabinet of curiosities that was popular. It included a deformed fetus and some curious man-made items. One was a mechanical wooden mouse covered with a mouse hide. Another was "snake-stones," which could supposedly heal bites from venomous snakes, per the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Cabinets of curiosities were forerunners to modern museums

Collecting oddities may have begun with the elite, but the idea was eventually adopted by everyone who was interested in spreading knowledge (via The Collector). But as time went on, smaller collections gave way to larger ones, and these extensive reserves were actually predecessors to modern museums. Some collectors wanted their treasures to live on after their deaths, and donated them to the public domain. The University of Oxford was the first public institution to receive a private collection, and in 1683, the Ashmolean Museum opened. About 100 years later, the British Museum (1759) and the Louvre (1793) opened their doors to the public, according to Britannica.

People are naturally inquisitive, which is probably why cabinets of curiosity were so popular to begin with. It's also likely the reason why there currently are 103,842 museums worldwide, with 33,082 of them housed in the United States, per Statista.