Who Is Nan Goldin, And Why Is She Leading The Charge Against The Sackler Family And OxyContin?

It isn't exactly a secret that artists draw on their life experiences — tragedies and all — to make their work. And sometimes, that art can be a catalyst for activism and change. That is certainly the case of the celebrated American photographer Nan Goldin, whose work over the course of decades has captured LGBTQ+ subcultures, the HIV/AIDS crisis, and the opioid epidemic. Her visceral style has earned her the nickname "the queen of hardcore photography" (via The Guardian) for her unvarnished looks at realities unfamiliar to the majority of its viewers. As she told the MOCA Los Angeles (via YouTube) in 2013, "I didn't care about 'good' photography, I cared about complete honesty."

For Goldin, that honesty started at a very young age. In 1965, when Goldin was just 11 years old, her older sister, Barbara, died by suicide, which had a profound impact on Goldin — and became the subject of a slideshow and her first book. "I saw the role that her sexuality and its repression played in her destruction," Goldin wrote in "The Ballad of Sexual Dependency," per The New Yorker. "Because of the times, the early '60s, women who were angry and sexual were frightening, outside the range of acceptable behavior, beyond control. By the time she was 18, she saw that her only way to get out was to lie down on the tracks of the commuter train outside of Washington, D.C. It was an act of immense will."

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Her activism was personal

In the 1980s, Nan Goldin began a project on the AIDS crisis in America, focusing on her community in New York. It culminated in a 1989 show of text and photography, "Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing." It featured artists — drag queens, transgender performers, and LGBTQ+ actors — who had been stricken by the crisis. "They were my life. I lost all my friends. And you can't find people like that again. All the people that had my history," Goldin told the Financial Times. "All the people that I was meant to get old with. I've lost my community. I've had friends since. But I don't have a community like that again." Putting Goldin's name behind the show, which presented the LGBTQ+ community in a way that depicted their reality, fueled the activism calling for AIDS research and for basic human recognition, per the Whitney Museum of Art.

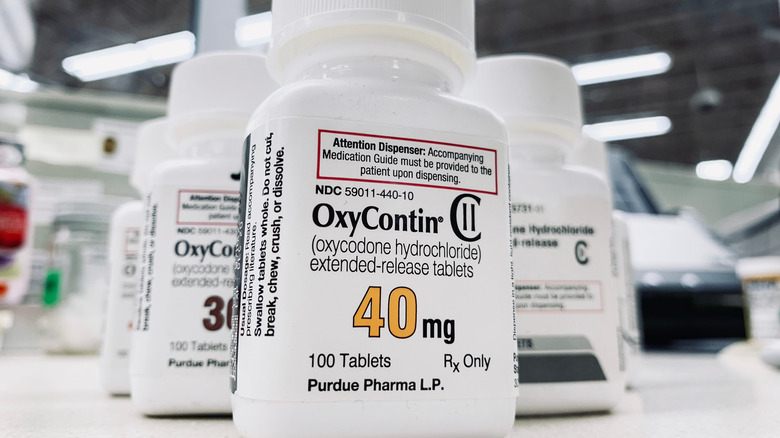

In 2017, Goldin channeled her art and activism in a different direction: the opioid epidemic. And, once again, it was personal. She became addicted to OxyContin following a post-surgery prescription. In the 1970s and 1980s, Goldin had a heroin addiction, so she knew the damage opioids could do. Still, she felt confident using OxyContin. "I had heard it was a really evil drug, but I didn't think it would do me," she told The New York Times T magazine in 2018. "I thought I had a lot of control."

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

Goldin's addiction was a catalyst for activism

Nan Goldin's prescription for three pills a day that were initially too strong for her (per Artforum) became a habit that rose to 18 a day. "The first time I got a 'scrip it was 40 milligrams and it was too strong for me; they made me nauseated and dulled. By the end, I was on 450mg a day," Goldin told The Guardian. She spent all the money she had on her OxyContin addiction, including money from a private endowment. When doctors and pharmacists realized she was burning through her prescription too quickly, she turned to illegal providers. And when she couldn't afford the OxyContin, she looked for other highs and nearly died when she snorted fentanyl, thinking it was heroin.

She spent nearly three years addicted to opioids. But when she reached a rehab facility in Massachusetts in 2017, she began to look into how this could happen so easily. What she learned was that she was hardly alone. At that point, nearly a quarter-million people had died from opioid addiction since 1999 (in 2022, that number is well above 500,000, per The New York Times). Angered and reminded of the AIDS crisis, Goldin wanted to know who was responsible. Her research led to Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family, which owned the company. "I don't know how they live with themselves," she later told The Guardian.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

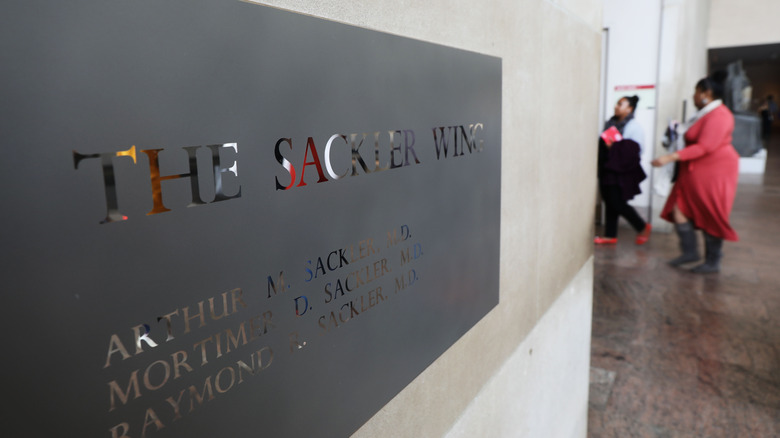

She targets museums and the Sacklers

When Nan Goldin left rehab, she set her sights on the Sackler family. Once again, she used the angle she knew best: art. She began by targeting the art world, which for decades had been more than happy to accept philanthropic donations from the Sackler family. This often came with the family name on the wings of the most prestigious art museums in the country, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim. Goldin co-founded the group PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) and gathered members to protest at the museums that had taken Sackler money. According to The New Yorker, they would chant, "Sacklers lie, thousands die!" and would throw fake prescription bottles in the reflecting pool and fountains before staging a die-in. The Tate Museum in London was the first to remove the Sackler name. In the U.S., it was the Guggenheim and then the Met, per the BBC.

In 2022, the Sackler family reached a settlement with the federal government to pay out $6 billion for its part in the opioid crisis, according to Reuters. For all the destruction the opioid crisis has caused the world — including her own addiction, brush with death, and subsequent activism — Goldin still has complicated feelings about the drug's allure. "[Opioids] make everything all right. They're like a padding between you and the world," she told The New York Times' T magazine. "It's this round warmth that's covering you. Everything is bearable suddenly."

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).