Battle Of Iwo Jima Stories You May Not Have Heard Before

The volcanic island of Iwo Jima, located in the Pacific Ocean 660 miles south of Japan, is barely 8 square miles of territory. Yet, during World War II, it was witness to some of the deadliest battles and most destructive fighting of the entire Pacific Front. According to the National World War II Museum, the Allies' hunt for Iwo Jima started in late 1944 in response to Japanese fighter planes stationed on the island. They were causing setbacks for both the Allied bombing and island-hopping campaigns, and within months Marines were on their way to solving the problem.

The Battle of Iwo Jima lasted from February 19 to March 26, 1945, when the Marines finally declared victory. The Marines had more than three times the amount of troops than the Japanese but actually incurred more overall casualties (27,000) than their opponents. The Japanese, however, had a killed-in-action rate of over 95%, as nearly all of their 20,000 soldiers fell during the savage fighting.

While the days of warfare on Iwo Jima have thankfully long since passed, the 90,000 soldiers who fought on that island in the South Pacific in the winter of 1945 forged powerful memories and stories that far outlived the fighting. These are the Battle of Iwo Jima stories and the lesser-known heroes you may not have heard of before.

The unfortunate photo mix-ups

Since it was taken on February 23, 1945, the iconic photo of the U.S. Marines raising the American flag on Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima island has stood as a powerful symbol of the tragic battle. It features six Marines raising a single flag and is one of the most famous and recognizable photos in American military history. However, while the image is incredibly famous, it's also not the clearest of pictures either, owing to 1940s photography equipment and the fact that it was taken in the midst of battle. As a result, it hasn't always been easy to determine exactly who of the nearly 70,000 Marines that took part in the battle are in the photo.

According to The New York Times, the first misidentification was realized the year after the photo was taken, in 1946, when the Marine Corps announced that they had mistakenly identified Harlon Block as Henry Hansen. Though there were suspicions, it wasn't until 2016 that another misidentification was discovered. This time, it was determined that Harold Schultz had been wrongly attributed as John Bradley. Schultz, who died in 1995, reportedly knew that he was the Marine in the picture, but refused to take credit out of modesty.

Most recently, in 2019, another misattribution was found. This time, researchers discovered that Harold "Pie" Keller had been wrongly identified as Rene Gagnon (via NBC). Reportedly, Gagnon still had a part in the flag-raising but was not in the actual picture.

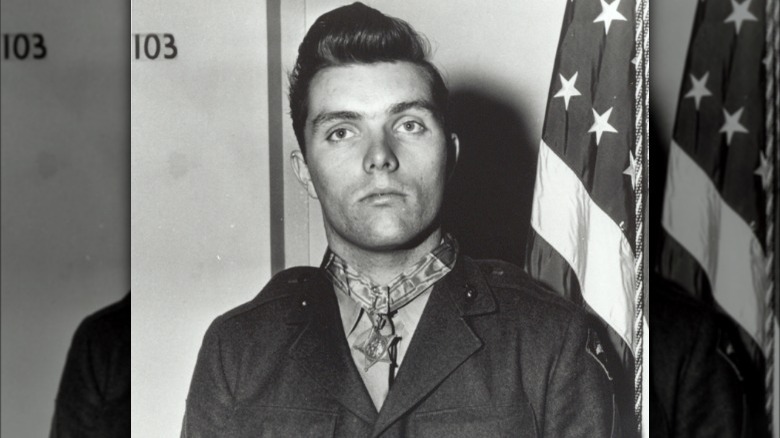

Hershel 'Woody' Williams earning the Medal of Honor

On June 29, 2022, the world lost one of the Battle of Iwo Jima's great heroes. As reported by The New York Times, Hershel "Woody" Williams died at the Huntington Veterans Affairs Medical Center at the age of 98. Williams earned the Medal of Honor for his actions while fighting at Iwo Jima, and was the last living medal recipient from World War II. Williams was just 21 and a corporal in the Marines at the time of the battle, and he fought incredibly bravely during his time in the service.

At Iwo Jima, Williams' primary weapon of destruction was a flamethrower, and he used it to devastating effect. He took out more than half-a-dozen enemy strongholds, dodging bullets and weaving through enemy lines. Williams was one of just 27 Marines and Seamen who earned the medal on Iwo Jima and fought as part of the 21st Marines of the 3rd Marine Division.

Originally born in 1923 in West Virginia, Williams joined the Marines in 1943 and soon found himself fighting in the South Pacific. According to the Department of Defense, Williams single-handedly took down several Japanese pillboxes after all of the other flamethrower specialists had been killed. Williams received his medal from President Harry Truman a few months after the war ended, and in 2020, the U.S. Navy commissioned the U.S.S. Hershel "Woody" Williams in his honor.

There were two flag raisings

Most people are undoubtedly familiar with the iconic photo taken by Joe Rosenthal of Marines raising the American flag over Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima. However, they often do not realize that there were actually two flag raisings done on Suribachi that day, and the iconic photograph from Rosenthal is actually the second of the two. The first flag raising was done by six marines, including Charles W. Lindberg, and there was a picture taken of it by U.S. Marine Corps photographer Sgt. Louis Lowery (via The New York Times).

When it happened on February 23, 1945, the Marines fighting throughout Iwo Jima immediately made noise to celebrate the triumph (per Military.com). Yet apparently, the flag wasn't big enough, as Lt. Col. Chandler Johnson had the first flag taken down and replaced with a larger flag, while the original was kept for safekeeping.

While Lowery was a Marine at the time, Rosenthal was a civilian working as a photographer for the Associated Press, and for whatever reason, it was the second photo that became more popular. It's likely due to the fact that it was published first — less than a day after being taken — and it won the Pulitzer Prize later in the year. Today, a sculpture replica of the second photo sits in Washington D.C., which was originally built in the 1950s.

William Genaust, the other Iwo Jima photographer

While many people are familiar with Joe Rosenthal, the photographer from the Associated Press who shot the famous photo of the Marines raising the U.S. flag at Iwo Jima, the story of William Genaust (above left) is much less known. Genaust was a photographer and sergeant in the Marine Corps at Iwo Jima, and he was using a primitive video camera to capture footage of the battle (via the St. Cloud Times). Though most people do not realize it, he was actually right next to Rosenthal when he took the iconic picture. Genaust captured 198 frames of the flag raising on his camera, and they were often used to defend Rosenthal's photo from accusations of fakery.

Unfortunately, Genaust died shortly after taking the footage, when he was trying to get more pictures in a cave on Hill 362A. Initially listed as Missing in Action, it was later determined he had been killed by Japanese soldiers. Following the footage's release, it was featured in motion pictures like the famous John Wayne WWII film "The Sands of Iwo Jima." His legacy still lives on in the annals of the Second World War, and in the hearts and minds of countless Americans thankful for his service.

The final Japanese hold-outs in 1949

As incredible as it might sound, not everyone got the message that the Battle of Iwo Jima ended in March of 1945. On January 10, 1949, nearly four years after the last shots were fired, the military newspaper Stars and Stripes reported that two Japanese sailors, Matsudo Linsoki and Yamakage Kufuku, had emerged from hiding on the island. Though there was nothing to verify their story, they claimed to have been from the former Imperial Japanese Navy and said they had been hiding out in the caves since February of 1945.

When they surrendered to U.S. forces in 1949, they were wearing American uniforms and had been living a nocturnal existence since the battle, wary of being found out and caught. Apparently, they had made a makeshift shelter in a cave, consisting largely of abandoned U.S. military supplies, and had even been giving each other regular haircuts. They had not even realized that the war was over, only finding out when they came across a newspaper just days before they turned themselves in.

One of the men, Kufuku, actually found his way back to Iwo Jima several years later. But tragically, after being unable to find his long-lost diary, he died by suicide off one of the island's cliffs (via "The Ghosts of Iwo Jima").

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Douglas T. Jacobson and his bazooka

When he was still just a teenager, Private First Class Douglas T. Jacobson answered his country's call and found himself as part of the 3rd Battalion, 23rd Marines, 4th Marine Division, stationed at Iwo Jima. Already a veteran of several Pacific island campaigns, Jacobson was one of the earliest Marines to arrive at Iwo Jima in late February (via the National World War II Museum). While fighting on Hill 382 at an area dubbed "the meat grinder," he performed some of the most heroic and incredible feats of the whole battle, and maybe even the entire war.

Although a bazooka usually needs a couple of pairs of hands to operate, Jacobson armed himself with one solo and proceeded to destroy anti-aircraft guns, machine gun positions, and pillboxes, as he pushed through the Japanese defenses. It's estimated Jacobson took out 75 Japanese soldiers and as many as 16 different enemy positions with his bazooka, which he recovered from another dead soldier. Along with Hershel Williams, Jacobson was one of just 27 Marines to earn the Medal of Honor for his bravery at Iwo Jima.

Jacobson died in September 2000 at the age of 74, as reported by The New York Times. After Iwo Jima, he was later promoted to Major in the Marines and served as a helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War. Jacobson dropped out of high school to fight in WWII, and he earned his general equivalency diploma in 1967 while in Vietnam.

The Zippo Tanks

To defeat the Japanese at the Battle of Iwo Jima, the U.S. Marine Corps had to get creative. To that end, in order to supplement the 70,000-odd force put onshore, the Marines also used Sherman M4A3 medium tanks equipped with Navy Mark I flamethrowers — affectionately known as Zippo Tanks (per the National Parks Service). These tanks had their machine guns removed in order to accommodate the flamethrowers, some of which could spew flames upwards of 150 yards, and they were somewhat unwieldy to pilot. Still, they were invaluable during the battle, and some of them could continuously run their flamethrower for longer than a minute.

There were eight total Zippo tanks at Iwo Jima, and some Marines even claim that they were the reason they ultimately won the battle. They could go where Marines couldn't, as their bullet-resistant armor allowed them to drive under heavy fire right up to Japanese fortifications and burn them to the ground. The Marines had first begun using flamethrowers just over a year prior, and they had previously been used during the prior Marianas and Peleliu Island campaigns. At Iwo Jima, the Marines used as much as 10,000 gallons of fuel with napalm added to it per day to fuel the tanks.

Charles W. Lindberg and his flamethrower

Charles W. Lindberg was still just a young man when he served with the U.S. Marines at the Battle of Iwo Jima in 1945. His image was forever linked with the battle when Marine Corps photographer Sgt. Lou Lowery took a picture of him raising the American flag on Mount Suribachi (per The New York Times). Though not the iconic picture by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal that most people have seen, the picture of Lindberg and his fellow Marines raising a flag is every bit as important and heroic.

Lindberg was part of the first group of flag raisers, who actually placed a flag on Suribachi four hours before those in Rosenthal's picture. Though many people tragically refused to believe him when he told them he was a part of it, Lindberg always remained very proud of his role in the first flag-raising.

Lindberg fought at Iwo Jima for several days, eventually earning both a Purple Heart for an arm wound and a Silver Star for exceptional bravery. Lindberg was a corporal at the time and stayed in the Marines until 1946 when he was discharged and later started working as an electrician. Like Hershel Walker, Lindberg was very effective with a flamethrower at Iwo Jima, using it to clear enemy pillboxes with devastating proficiency. Lindberg died in 2007 in Edina, Minnesota at the age of 86.

J.D. Dud Morris hauling Marines

The U.S. Marine Corps was not the only part of the American military fighting at Iwo Jima. Right alongside them were members of the U.S. Navy, including Boatswain Mate 2nd Class J.D. "Dud" Morris. According to Morris himself (via D. Clarke Evans Photography), he landed on the first day of the fighting as part of the fifth wave. Immediately upon landing, he witnessed incredible amounts of destruction and fighting, seeing the beaches littered with dead and wounded American boys.

From his vantage point, Morris was able to witness the planting of the flag on Mount Suribachi, and he ended up staying on the island for more than a year. His job during the battle was to "haul Marines in and out" of Iwo Jima, which exposed him to fire and was immensely dangerous (via Spectrum News 1). In addition to taking Marines to the island, he also helped rescue pilots who had to abandon their planes and bail out into the ocean (via Fox 7 Austin).

Though he lost part of his hearing, Morris still fondly remembers his lifelong connections from his days in the Navy, and until recently he and members of his former unit would meet up for reunions. Thought to be the last surviving member of his Navy unit, Morris still lived in his hometown of Elgin, Texas as of 2022.

Don Graves and his ascent up Mt. Suribachi

Corporal Don Graves was one of the first Marines that landed on the island of Iwo Jima, arriving as part of the third wave (per Graves via D. Clarke Evans Photography). He was a member of the 5th Marine Division and came ashore just a few hours after sunrise on February 19, 1945. He was one of 335 members of the 2nd Battalion, and one of only 18 to survive the entire battle. Immediately pinned down by the enemy fire, Graves and his squad mates had to crawl, literally inch-by-inch, just to get off the beach. After climbing the harrowing 540-foot Mount Suribachi, Graves was actually just next to those being photographed in Joe Rosenthal's famous photo.

Equipped with a flamethrower, Graves methodically cleared pillboxes to help the Marines overcome the Japanese defenses, and witnessed famous Marine hero John Basilone die. During the fighting, Graves had an incredibly cathartic religious awakening, saying he was "converted ... on the beach at Iwo [Jima]." As of 2023, Graves was a board member of the State Funeral for World War II Veterans organization.

Reflecting on his experiences in early 2021 for Spectrum News 1, Graves recalled his time at Iwo Jima, explaining that he was still troubled nearly 80 years later by some of the horrifying things he experienced. Graves was wounded on Iwo Jima but survived to spend his life mainly in Wisconsin and Texas, having four children and becoming a minister.

Bill Montgomery almost died from friendly fire

Recollecting on his experiences 75 years later, Bill Montgomery said "I felt ecstasy!" when talking about watching the flag being raised on Mount Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo Jima (via National Geographic). Montgomery was one of the 70,000 Marines who fought at Iwo Jima, being one of the few members of his unit to have survived. He landed on the first day of fighting and fought until the bloody end more than 30 days later, while more than 26,000 of his fellow Marines and Navy men became casualties.

Montgomery was sitting in a foxhole when the flag was raised, five days into one of the most hellish operations of the war. Initially, the Marines expected there to only be light resistance, but instead, they met a fierce group of Japanese invaders willing to hold the island at all costs. He was almost blown up by a volley of Japanese grenades one night and nearly killed by friendly fire another. An Allied Mustang P-51 fighter-bomber had thought he was a Japanese soldier, and Montgomery barely escaped the ensuing bombing.

While stationed on Iwo Jima, Montgomery watched the mental decline of many of his fellow Marines in World War II's aftermath who struggled to understand and deal with what they had been a part of. Montgomery himself was tasked with picking up the limbs and bodies of dead Marines from the island, an incredibly difficult and disturbing job.

The Marines return to Iwo Jima

In March of 1995, many veterans of the Iwo Jima campaign returned to the war-torn spot they had fought on to commemorate the battle's 50th anniversary. According to The New York Times, there were more than 500 former American Marines at the event, and there were also Japanese veterans, too. In March of 2005, many returns made the trip back for the battle's 60th anniversary. As The New York Times reported, the veterans, most of whom were now octogenarians, recalled their experiences from the battle, their hands now outstretched for handshakes instead of grasping automatic weapons.

In addition, there were descendants from both the American and Japanese veterans of Iwo Jima, as that was part of the theme of the reunion. While touring the island, the former Marines were able to recognize places they had previously fought at, including one who remembered where former New York Giants tight end Jack Lummus succumbed from his wounds. According to the Associated Press, Lummus had died after stepping on a landmine, and Marine Gerry Russell had comforted him as he was going into shock, which he recalled for The Times 60 years later.