Authors Who Had Tragic Deaths

There are few professions more romantic than that of a writer, which is one reason why so many people want to do it. Even those who have made their names in other fields often turn to writing, in part for the intellectual kudos it seems to bestow, as well as for the bohemian air one gets from being described as a "poet" or "novelist." Celebrities who have dipped their toe in the world of letters include Sean Penn, sisters Kendal and Kylie Jenner, and Tom Hanks (whose short stories are, apparently, pretty good).

But the writing life isn't always what it's cracked up to be. A lonely vocation in a highly competitive industry, writers of literature often struggle with self-doubt, professional disappointment, and the harsh reality that real life doesn't stop for the sake of art. And when it comes to how writers' lives sometimes end, it seems that they are second only to rock stars in terms of how many authors who are famous today suffer tragic fates, were cut down in their prime, or else died without the chance to reach their full potential.

Here are some of the biggest names in the world of literature who died tragically, though their works live on.

Ernest Hemingway

The American writer Ernest Hemingway was a towering figure in the world of literary modernism, with a distinctive style that generations of budding writers have imitated over the decades. Known affectionately as "Papa," he has also grown to become a paragon of 20th-century masculinity.

As a young man, Hemingway was a big game hunter, a fisherman, volunteered in the Spanish Civil War, and was fond of bullfighting. But even in later life, his reputation as a man of action preceded him. However, the truth was that in his final years the "For Whom the Bell Tolls" author suffered from failing health, including hypertension and advanced hepatitis. On July 2, 1961, the 61-year-old Nobel Prize winner died by suicide; the scene pointed to a death eerily reminiscent of that of his father, Clarence, who had shot himself in 1928.

In recent years, experts such as Christopher D. Martin have sought to analyze the circumstances of Hemingway's tragic death, noting that he may have suffered from bipolar disorder and a traumatic brain injury, possibly as a result of two plane crashes he survived in 1954.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

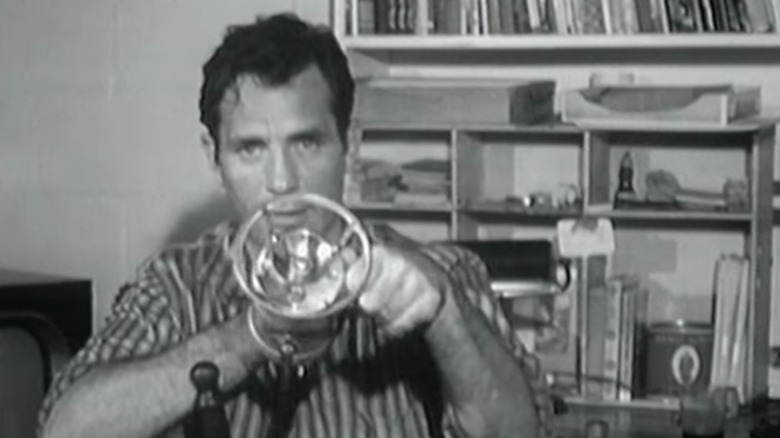

Jack Kerouac

The "King of the Beats" Jack Kerouac has remained a countercultural icon since his death in 1969. While the French-Canadian author left behind, dozens of novels and reams of poetry written in his iconoclastic "spontaneous" style, it is one work in particular, his 1957 classic "On the Road," which became a cornerstone of the Beat Generation and has remained a literary rite of passage for radical-thinking adolescents.

Though Kerouac and others of his generation were crucial in paving the way for the hippie movement that would later emerge in the U.S. in the 1960s, his biographer Ann Charters argues the writer wasn't as turned on to their politics as other Beats such as Allen Ginsberg would prove to be. He retreated from the limelight, settling in Florida with his third wife Stella Sampas to care for his ailing mother.

However, Kerouac himself was also not well. His health had deteriorated from decades of heavy alcohol use, and Charters claims he was also suffering from a hernia. He died from an abdominal hemorrhage at the age of 47. Charters also notes that Kerouac himself suspected that he had suffered brain damage, which contributed to the effect alcohol had on him, a theory that has gained more traction in recent years.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

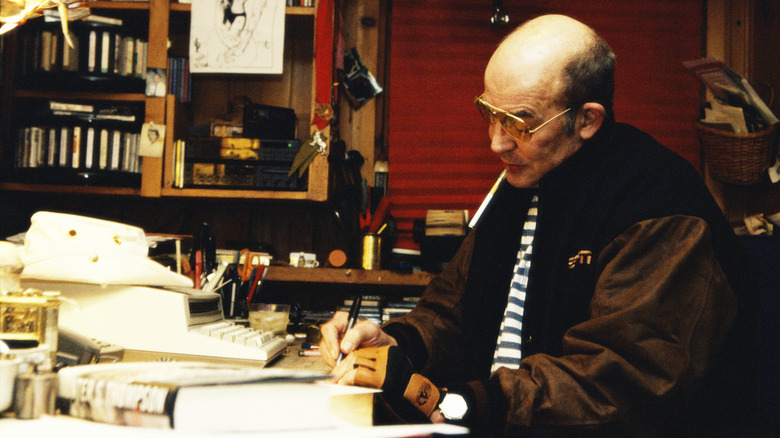

Hunter S. Thompson

Yet another cult hero who shocked his fans by dying in depressing circumstances was Hunter S. Thompson, the creator of a brand of extravagantly-written investigative journalism, that came to be known as "Gonzo." Thompson made his name writing for magazines such as Rolling Stone and in his early days published a book about his turbulent travels with the outlaw motorcycle gang Hells Angels. But it was his depraved, drug-addled novel, "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas," which was later transformed into a classic movie starring Johnny Depp — who himself is a devoted Thompson fan — that has really stuck in the popular consciousness.

According to a number of his friends quoted in "Gonzo: The life of Hunter S. Thompson," suicide was a subject that Thompson had discussed for decades. But when he died by suicide on February 20, 2005, it deeply shocked those close to him, including his son, Juan, who was in the house at the time and discovered his father's body.

Thompson's wife, Anita, later found a note, believed to have been written four days before Thompson's death, which was titled "Football season is over." It read: "No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No fun — for anybody. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax — This won't hurt."

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Zelda Fitzgerald

Zelda Fitzgerald is often dismissed as the "socialite" wife of her celebrated husband, the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald, who wrote the Great American Novel, "The Great Gatsby," published in 1925. But Mrs. Fitzgerald was herself also a talented writer in her own right, whose artistic prowess only began to be truly appreciated in the latter decades of the 20th century following the publication of Nancy Milford's "Zelda: A Biography," in 1970. Her 1932 novel, "Save Me the Waltz," is now considered a classic.

Zelda had many other artistic interests other than the single novel on which her current reputation is based, and she had been planning to write another novel. Sadly, as Milford describes, in the final years of her life she suffered from mental health issues that meant she was often in institutions receiving excruciating psychiatric care, such as electroshock therapy.

Her death in March 1948 was horrifying. Zelda was being given treatment at a mental institution called the Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, which included, according to Milford, several shots of sedative insulin, after which she was locked in a secure room. One night, a fire broke out, and the author, with no way of escaping, was incinerated, one of nine women who died in the hospital. She was 47.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

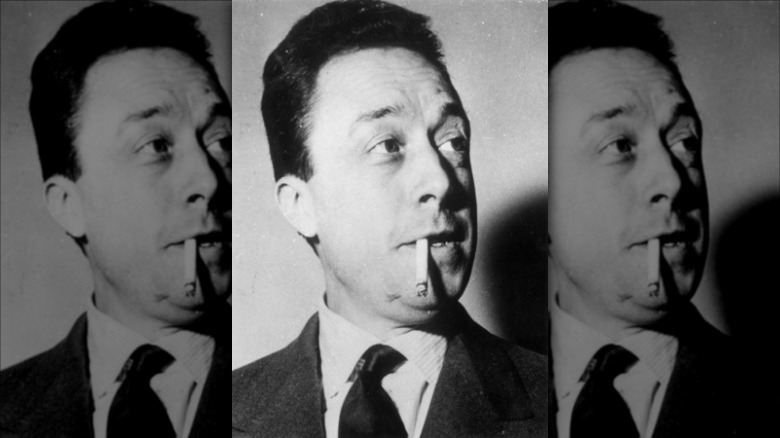

Albert Camus

The Algerian writer Albert Camus is one of the leading lights of 20th-century existentialism, whose contention that life itself is inherently absurd runs through his best-known novels such as "The Stranger" and "The Plague." Indeed, Camus himself characterized the two overarching themes of the first two stages of his career as the absurd, followed by revolt; the next stage he claimed to be moving on to was "love," a theme that biographers believe he would have dwelled upon had he lived beyond his tragic death at the age of 46.

Per Britannica, Camus died on the afternoon of January 4, 1960, when the car in which he was traveling with his friend, Michel Gallimard, and Gallimard's wife and daughter, collided with a tree on their way to Paris. Camus died instantly, while Gallimard died from his injuries days later.

For years the author's death was roundly considered a tragic accident. However, as the years went on, rumors spread that Camus was in fact assassinated by the KGB for criticizing the Soviet genocide in Hungary. However, the same source notes that while these rumors have persisted, they have never been verified, and many experts have rejected them outright.

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf was one of the towering figures of literary modernism, whose most famous novels written during the 1920s and 1930s — such as "To The Lighthouse," "Mrs. Dalloway," and "The Waves" — pushed the boundaries of how consciousness was portrayed in fiction and stand as hallmarks of multifaceted characterization in western fiction. Her maxims on the writing life, including that writers should "publish nothing before you are thirty," and that one of a woman writer's basic needs is "a room of one's own" have become fundamental pieces of wisdom in literary circles.

But despite her literary successes, Woolf had a difficult life. In a chapter titled "Abuses," Woolf's biographer Hermoine Lee charts the writer's early life as a lonely adolescent intellectual, emotionally abused by her father, and possible sexual abused by other male relatives. In later life, Woolf suffered from numerous bouts of mental illness that were diagnosed during her lifetime as "madness," but which experts today have characterized as potential bipolar disorder.

Woolf spend the final years of her life in the U.K., where she lived with her husband, Leonard, and as World War II gripped Europe, Woolf's mental health deteriorated. Her life ended on March 28, 1941, when she died by suicide near her home in Lewes.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Franz Kafka

The sense of bewilderment, paranoia, and otherworldliness summoned by the word "kafkaesque" has taken on a life of its own in the 20th century, while the Czech writer to whom it alludes, Franz Kafka, is today hailed as a revolutionary iconoclast whose style has gone on it influence theater, cinema, as well, of course, as other writers.

Kafka died tragically young, at the age of just 40, having suffered for many years from laryngeal tuberculosis. In his final days, his throat became so painful that he was unable to eat, weakening him irreversibly. His friend, the Israeli author Max Brod, was with him in his final days. According to The New York Times, it was to Brod that Kafka gave his final request: that the body of work he left behind was to be burned (Kafka himself is believed to have been an avid destroyer of his own literary artifacts, burning an estimated 90% of the writing he created in his lifetime).

Brod, of course, ignored his friend's request. And while in doing so he gave the world a gift — the work of a great artist who had no interest in achieving fame in his own lifetime or after — legal battles have raged ever since Kafka's death in 1924 between rival parties claiming ownership over his oeuvre (per the same source).

John Kennedy Toole

John Kennedy Toole's 1980 novel "A Confederacy of Dunces" is famous today as a comic masterpiece of American literature, with a cast of eccentric characters — including the gluttonous and misanthropic protagonist, Ignatius J. Reilly — whom readers are unlikely to soon forget.

But Toole himself was tragically unable to experience the literary success that he craved during his short life. As recounted in Cory MacLauchlin's "Butterfly in the Typewriter: The Tragic Life Story of John Kennedy Toole and the Remarkable Story of A Confederacy of Dunces," the New Orleans native began writing his novel as early as 1963, while performing military service, completing it the following year after his discharge and taking on a job as a college teacher. Convinced of the value of his work, he sent an unsolicited manuscript of the novel to the prestigious publishing house Simon & Schuster, beginning a long correspondence with the editor Robert Gottlieb. Gottlieb admired Toole as a writer but deemed that "A Confederacy of Dunces" was unpublishable without major rewrites, to which Toole was unwilling to commit. As late as 1966, Gottlieb was still sending Toole words of encouragement, but eventually, Toole abandoned his novel, dispirited by what he considered a rejection.

Toole died by suicide on March 26, 1969, at the age of 31. In her grief, his mother, Thelma made it her personal mission to have "A Confederacy of Dunces" published, and eventually succeeded in 1980. It won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1981.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988 or by calling 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

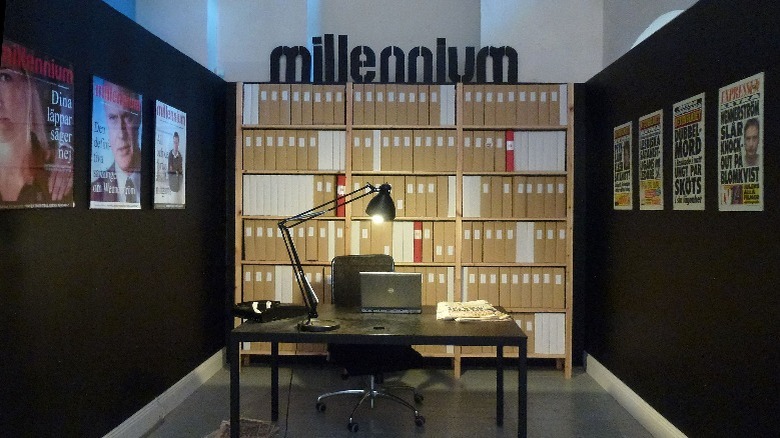

Stieg Larsson

Even if you don't know the name Stieg Larsson, you are sure to be aware of the Swedish crime writer's compelling work. His posthumously published "Millennium" series, the first volume of which is titled "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo," became a crime sensation, before spawning a number of movies in Swedish which were then turned into lucrative Hollywood remakes.

Larsson himself died suddenly in 2004, having suffered a heart attack after climbing the stairs to his office. He was 50. Sadly, Larsson did not leave a will, and after the explosion of interest in his work after the publication of "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo," a furious legal battle ensued between his partner — to whom he was unmarried — and his blood relatives over who should control his estate, which in 2009 was valued at $30 million (per Vanity Fair).

With the posthumous success of Larsson's work, readers have shown continued interest in reading stories set in the world that he created. In recent years, his estate has brokered deals for more "Millennium" books to be penned by the writers David Lagercrantz and Karin Smirnoff.

Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Pushkin, who was born into Russian nobility in Moscow in 1799, is one of the greatest names in Russian literature, whose mastery of the Russian language and uncanny ability to get to the core of the psyche of a nation informed many of the literary giants who came after him, including Nikolai Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Something of a literary prodigy, Pushkin became an established star in his adolescence, but it was his hit verse-novel, "Eugine Onegin," which was published in serial form between 1825 and 1832, that made him a sensation in the world of Russian letters. According to Pushkin's biographer, T. J. Binyon, the young protagonist of the work in question is a semi-autobiographical rendering of the writer himself, whose life in St. Petersburg was modeled on Pushkin's own. The novel ends tragically, and in a cruel twist of fate, Onegin and his creator were to meet the same fate: death in a duel.

Per Binyon, Pushkin's duel was with a French soldier, Georges d'Anthès. D'Anthès became Pushkin's brother-in-law, but there were rumors that he was also having an affair with the writer's wife, which came to a head after the circulation of anonymous letters calling Pushkin "Coadjutor to the Grand Master of the Order of Cuckolds and historiographer of the Order." D'Anthès shot Pushkin fatally on the morning of February 8, 1837, and he died two days later. He left behind his wife, Natalia, and four children. He was 37, and his death plunged his homeland into deep mourning.

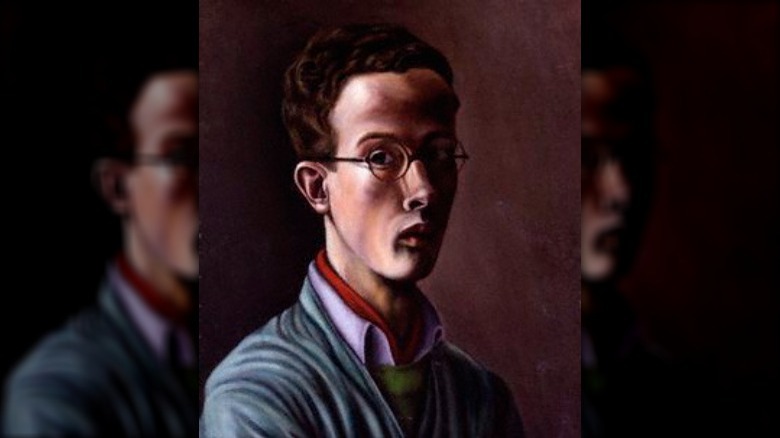

Denton Welch

The British author and painter Denton Welch came from a family of great wealth and opportunity. His father, Joseph, was a merchant with ties to China, and Welch — who was born in Shanghai in 1915 — spent much of his life commuting between there and the U.K. with his parents and older brothers.

Per the writer's biographer Robert Phillips, Welch's memoirs describe a sad and lonely childhood. Despite enjoying many privileges, he lacked the athleticism of his brothers and often felt isolated, and he was traumatized when his mother, Rosalind, died suddenly when he was just 11 years old. As a teen, he frequently ran away from school.

At 20, Welch had his own brush with death, when he was hit by a car while riding his bicycle. The collision fractured Welch's spine, paralyzing him and leading to a long period of recuperation, though he was left severely disabled for the rest of his life. He died at 33, though in the eight years prior to his death, he was exceptionally prolific, leaving behind numerous novels — including the semi-autobiographical "Maiden Voyage" — reams of memoirs, and countless paintings.

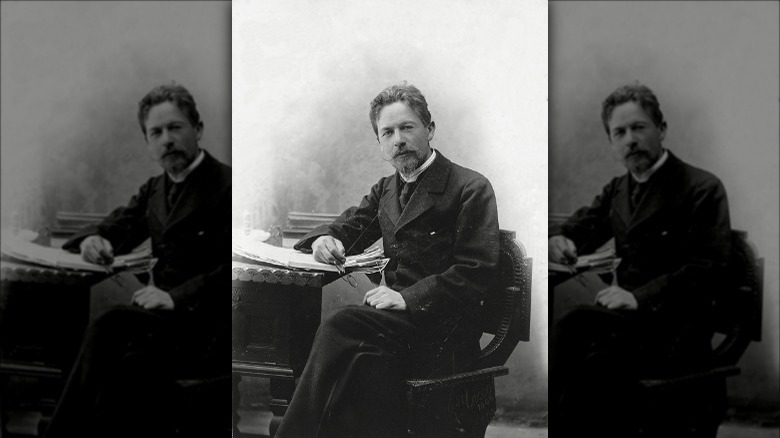

Anton Chekov

Anton Chekov was one of the most celebrated figures in 19th-century Russian literature, whose canon of short stories and plays such as "Uncle Vanya," "Three Sisters," and "The Seagull" received acclaim during his own lifetime, and have continued to compel audiences up to the present day.

Sadly, the towering author suffered an early death from tuberculosis in 1904, at the age of just 44. But despite the tragedy of his short life, critics have commented on the unusually poetic nature of Chekov's final moments; indeed, it could have been the closing scene of one of his own plays.

An account written by Chekov's wife, Olga Knipper, details how he was taken to his deathbed in Moscow, and was treated by doctors who administered drugs to ease his pain. Knipper claims that the writer declared "I am dying," after which champagne was ordered. He took a glass, smiled at his wife, and told her his final words: "It's a long time since I drank champagne."