Weird Things About Sacagawea You Didn't Know

Disney hasn't made a movie about her life (yet) but most Americans know her name — Sacagawea, the Shoshone woman who led explorers Lewis and Clark on an 8,000-mile journey to the Pacific Ocean. And if that's not remarkable enough, she did it while carrying her infant son on her back and without a single triple shot venti macchiato, which everyone knows is the only thing that keeps new mothers in a state of actual consciousness.

The story of the Lewis and Clark expedition is pretty well known, but the details about the only woman member of the party are vanishingly few. We know she was just 15 or 16 years old, we know she was valuable as both an interpreter and a guide, and we know her brother was a Shoshone chief. The more obscure details about her life are buried in the Lewis and Clark journals, in a few oral histories, and in the ground with her, though that hasn't stopped anyone from just making stuff up, because that's what Americans like to do. However, there are still a few tantalizing truths and maybe-truths about Sacagawea that haven't made it into the public consciousness yet.

Kidnapping as an infertility treatment

Sacagawea was Shoshone, but she spent the late part of her childhood living with the Hidatsa. At the age of 12, she was kidnapped during a raid and forced to travel hundreds of miles to a Hidatsa village.

What exactly her capture says about her status among the Hidatsa is debatable — according to the National Park service, the Hidatsa had no concept of slavery, so you can't really say Sacagawea was a slave even though that's a pretty common misconception. Rather, it was a common practice for the Hidatsa to kidnap the children of their enemies and then bring them home to replace deceased children or to fill the arms of childless couples, which avoided the problem of a long and arduous home study but was still a pretty unsavory way to enter into an adoption agreement. The good news is that abductees were treated like family and generally permitted to return home to their own tribe when they reached adulthood, if they didn't first get swapped to some French dude as payment for gambling debt.

When you think about it, the practice of kidnapping and adopting children from other tribes was actually a pretty genius way to introduce new genes into small populations, although not much can be said for the mental and emotional anguish it caused a lot of families and kids. And you thought it was scary sending your kid down to the corner to meet the school bus.

Because pronouncing things is hard

There were no recording devices during Lewis and Clark's time, and there also wasn't any consistency in the way people spelled things, so we can't really be 100 percent sure how to pronounce "Sacagawea." Lewis and Clark themselves both spelled her name with a G, but there's some confusion over whether it was meant to be a hard G (as in "logger") or a soft G (as in "strategic"). According to Straight Dope, Lewis wrote that Sacagawea's name was Hidatsa for "bird woman," which supports the hard G pronunciation but also opens up the possibility that the G was supposed to be a K, since the Hidatsa pronunciation could be either "SacaGawea" or "SacaKawea."

When the first edition of the Lewis and Clark journals was published, the editors, in their infinite editorial wisdom, chose to change the spelling to "Sacajawea," which probably led to the common pronunciation with a soft G sound. It also gave rise to the theory that Sacagawea's name was the Shoshone word for "boat launcher."

All that name business was evidently also too confusing for Clark, who ended up just calling Sacagawea "Janey" because he was the captain. The name didn't necessarily come from a place of endearment, though: "Jane" was army slang meaning "girl," so evidently Clark could not only not be bothered to get her name right, he also couldn't come up with anything better than a gender label.

A man of no peculiar merit

We kind of like to gloss over Sacagawea's marriage to French trapper Toussaint Charbonneau, because if you spend too much time really thinking about it you might actually barf. Charbonneau was described by his employers as "a man of no peculiar merit," but he was worse than that. He was a pedophile with more than one teenage wife, all of whom were native American, and a few years before the expedition he'd been stabbed by a Saultier woman while trying to rape her daughter. He was also a domestic abuser — he had a nasty temper and was known to hit Sacagawea when they disagreed.

Lewis and Clark didn't seem to think much of Sacagawea's husband — Lewis called him "the most timid waterman in the world" and later said he was mostly only useful to the Lewis and Clark expedition as an interpreter, though evidently he was also a fine maker of boudin blanc, which is a concoction of buffalo meat and kidneys served in intestine.

How Sacagawea came to be married to such a gross collection of human cells is not known for sure, but America's Library speculates that he might have "won" her gambling. It's probably at least safe to say it wasn't a love match.

Who needs pitocin when there are rattlesnakes all over the place?

Charbonneau was hired for the expedition in the winter of 1805, with a caveat — he had to bring his wife. Sacagawea could speak Shoshone, and Lewis and Clark predicted they'd need a fluent speaker to help them obtain horses from the Shoshone tribe. There was just one small complication — Sacagawea was pregnant, and paid maternity hadn't been invented yet.

According to History, two months before their scheduled departure, Sacagawea went into labor. Lewis was called in to assist the delivery, and noted that it was "tedious and the pain violent." So then, Lewis pioneered the natural childbirth practice of grinding up a rattlesnake tail and putting it in a cup of water because pitocin also hadn't been invented yet and evidently someone told him that would be a good idea. Within 10 minutes Sacagawea gave birth to a healthy boy named Jean Baptiste, and today we're all very thankful that Lewis didn't go on to write any books about obstetrics because no laboring mother wants pulverized rattlesnake tail served up with her ice chips.

Happily, there was no moratorium on breastfeeding in the workplace and Sacagawea wasn't being paid anyway, so she didn't really miss the maternity leave. Instead she just strapped her baby on her back and walked 8,000 miles, so you may now proceed to feel inadequate in your own ability to juggle work and family responsibilities.

Don't kill us, we have a baby

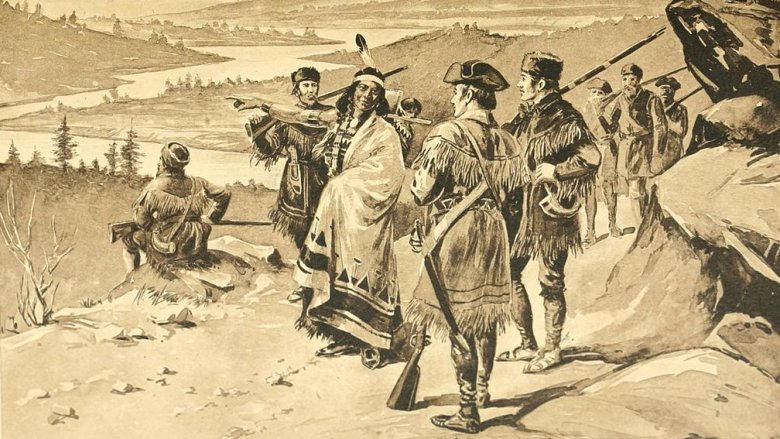

Sacagawea was more than just an interpreter. According to PBS, she was also a potent symbol of peace, kind of like a human shield only without all the action hero stuff.

The tribes Lewis and Clark encountered en route to the Pacific didn't exactly have a reason to trust strangers — native people were forever raiding each other, and some of the tribes had never before encountered Europeans so couldn't be sure of their intentions. But war parties don't travel with women and infants, and the fact that Sacagawea was a prominent member of the party probably supported the "we come in peace" image the expedition was hoping to project. So in other words, Lewis and Clark probably avoided major conflict just based on the universal understanding that bringing a baby to a war is bad parenting. Now if only we could also come to a universal understanding about some other things that are bad parenting, like public humiliation and creamed tuna peas on toast.

Important, but maybe not the key or anything

Over the years, Sacagawea kind of morphed into this legendary figure, which is pretty much what happens to all the world's historical figures except for Charbonneau and the guy who invented floss. So a lot of what's been said about her is not really trustworthy because her story was often rewritten to support a certain agenda.

Feminists, for example, loved Sacagawea because she was an example of a woman who could do motherhood and business on the same day and still have time to nurse sick explorers and get the best deal on Appaloosas down at the Shoshone market. Supporters of the racist ideals of manifest destiny loved her, too, because she represented the "good Indian" who understood the destiny of whites in America and helped them realize God's plan for European domination.

Neither of those personas is accurate, though over the years they've both led to a misconception that Sacagawea was more important to the success of the Lewis and Clark expedition than she probably was. Though she certainly was a valued contributor, there's not a lot of evidence that the expedition would have failed without her. According to Straight Dope, other native guides seem to have done more in the way of getting the expedition from A to B, and although communication would have been challenging if Sacagawea hadn't been there, the chances are pretty good that Lewis and Clark would have done okay without their famous interpreter.

Rescuing her own legacy from an overturned boat

The greatest ironies of Sacagawea's life are probably that she was a nice person married to a sucky human being and that her legacy was used to perpetuate ideas that were contrary to the interests of her own people. But the other lesser irony is that we might not know much about Sacagawea or the expedition at all if it hadn't been for her own quick thinking.

In April 1805, Charbonneau was steering one of the boats. Based on what we've heard, this seems like a bad decision, but whatever! He was steering the boat when a sudden gale nearly capsized it.

Now, Charbonneau was a pedophile and an all-around creep, but that doesn't necessarily mean he was a wuss, right? Nah, he was totally a wuss. He panicked, froze, and was only cajoled into action when one of the men threatened to shoot him. The boat, which contained "almost every article indispensably necessary to further the views, or insure the success of our enterprise," was righted, but not before it was partially filled with water and important papers had begun to float away.

Unlike her husband, Sacagawea kept her cool. According to PBS, she was the one plucking the papers out of the water as they floated by, thus saving all those indispensably necessary articles for future generations.

But she was OUR heroine

First King Arthur was Welsh, and then he was Cornish, and then he moved to California so Hollywood could make a bunch of really stupid movies about him. Just like King Arthur, Sacagawea was also claimed by more than one nation — while American history says she was Lemhi Shoshone, the Hidatsa have an oral tradition that says she wasn't Shoshone at all, but native Hidatsa, which means all that stuff about her kidnapping and adoption into the Hidatsa tribe and the tearful reunion with her brother that supposedly happened during the Lewis and Clark expedition would be total bunk.

According to the Reconesse Database, the Hidatsa story says she understood the Shoshone language merely because she'd hung out with them a lot, which seems odd given that the Shoshone and Hidatsa were enemies, but let's give them the benefit of the doubt. That's not where the implausibility stops, though, because evidently the tearful reunion with Chief Cameahwait was mere politeness and Lewis and Clark had simply misunderstood Sacagawea when she said Cameahwait was her brother. Does that mean Shoshone custom dictates one should always burst into tears as a matter of courtesy before beginning trade negotiations? Hmm.

Will the real Sacagawea please come back to life so we can get the death straightened out?

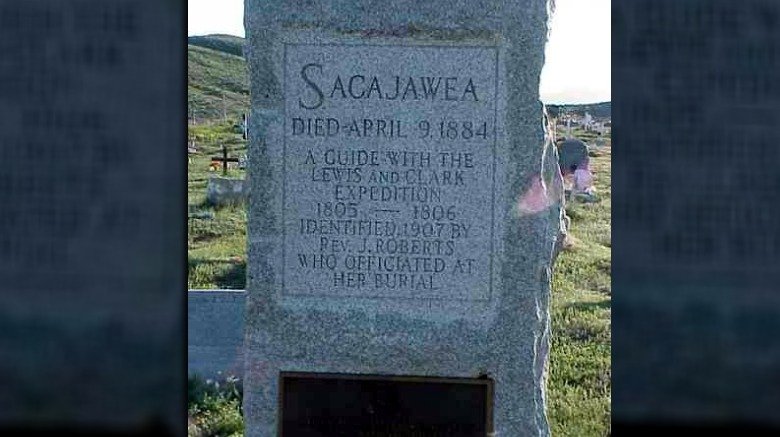

Historical figures must not only be morphed into legendary figures and claimed by multiple nations, but they must also be discovered still living somewhere in western America decades after their death. That's why in 1884 a woman who claimed to be Sacagawea died on the Wind River reservation in Wyoming. This is problematic because most historians think the real Sacagawea died in 1812, as noted by John C. Luttig:" "This Evening the Wife of Charbonneau, a Snake Squaw, died of a putrid fever she was a good and the best Woman in the fort, aged abt. 25 years she left a fine infant girl." Luttig didn't name names, but the details seem to point to Sacagawea, and the fact that Clark became her children's guardian not long afterward would boost the idea that she died in 1812.

On the other hand, the Wind River woman's story is somewhat convincing — according to the Sacagawea Historical Society, she claimed to have been part of the Lewis and Clark expedition and she had two sons, one of whom was called Baptiste. According to this legend, Sacagawea left Charbonneau and moved back to her ancestral home, where she died at the age of 90-something. The woman's story was convincing enough that she was buried under a tombstone marked "Sacajawea — a guide with the Lewis and Clark expedition." We may never know.

Mountains, rivers, hot springs and bad romance novels

California Indian Education says no other American woman is more memorialized than Sacagawea. Four states have mountains named for her, there's a Sacagawea River, a Sacagawea Hot Springs, and a Lake Sacagawea. Two military vessels have had her name, and her likeness has appeared on a couple of postage stamps. Some people also believe she's had more statues erected in her honor than any other American woman, though there aren't really any official statue counters who can confirm or deny that.

And then, of course, there are the stories — novels that called her an "Indian princess" or alluded to a love affair between her and Captain Clark, and the subsequent fictions that arose from all those other fictions, such as the 1916 claim that she'd converted to Christianity just before her death, because of course all American heroes must be whitewashed to make them more palatable to the average racist. That particular fiction first appeared in a pamphlet designed to trump up support for yet another Sacagawea statue — The Straight Dope speculated that it was mostly just a ploy to get everyone behind the potentially expensive memorial. Because clearly, America needs more Sacagawea statues.

Sacagawea the traitor?

White America has spent so much time gushing over Sacagawea that we hardly ever stop to think what she must have meant to her own people, but here's the thing — they don't necessarily revere her the way the rest of America does. Randy'L Teton, who modeled for the Sacagawea dollar coin, told the Idaho State Journal that Sacagawea's participation in the Lewis and Clark expedition was seen by many as an act of betrayal. "Even today, Sacagawea is not considered a heroine," Teton said. "She is thought of as a traitor. The elders thought she brought the white people to the land."

That sounds kind of shocking at first, but only because we're so used to seeing all those idealized portraits of the young Shoshone woman with a baby on her back, usually pointing at something and usually with the wind blowing her hair around, and it's really hard not to interpret those images as heroic. But Lewis and Clark weren't just on a journey of discovery — they were also there to tell the natives that the land no longer belonged to them and that there was a "great white father" in the east who was going to call all the shots now. That didn't mean much to the natives at the time, but in hindsight those were pretty devastating words, and it's easy to see how Sacagawea might have taken some of the blame for what happened next.

Sacagawea is big in Ecuador

Do you remember when the Sacagawea dollar coin was introduced in 2000? No? You're not alone. The U.S. Mint was evidently keen to repeat the failures of the Susan B. Anthony dollar and decided to put Sacagawea's face on the new coin, never mind the part where no one actually knows what Sacagawea looked like. The mint did at least have the courtesy to use a Shoshone model and to consult with the Native American community before deciding on the final design.

According to the Sacagawea Historical Society, the coin has been minted every year since 2000, and yet you probably still haven't ever actually had one in your wallet. So where did all the Sacagawea dollars go? Ecuador, as it turns out. According to the Miami Herald, Ecuador adopted the dollar in 2000, and Ecuadorians prefer dollar coins over paper dollars. Since 2002, the United States has shipped about $150 million in dollar coins to Ecuador, where they are widely circulated. (The ones that remain in the United States are usually set aside as keepsakes, which explains why you hardly ever see them.) Because Ecuador has a large indigenous population, it seems fitting that Sacagawea is truly appreciated there, even though many Ecuadorians aren't familiar with her very courageous and sometimes weird story.