The Worst Generals Of The American Revolution

It must be tough to be a wartime general. Though few of us are deeply familiar with the sort of demands such a job puts on a person, it's clearly a position that requires time, skill, intelligence, and honor. Well, for most people.

Take the generals of the American Revolution. Some served with their reputations intact — George Washington led the new nation to victory and is still on multiple forms of United States currency, while the French Marquis de Lafayette is practically legendary nearly 200 years after his death.

Yet, others went down in history as duds. Some were merely bad at their jobs, which is annoying if you have to work alongside them in an office but potentially deadly if they happen to be your commander on a battlefield. Others were opportunists, with some traveling from Europe to help the cause ... or join up with a theoretically desperate Continental Army to boost their ranks and careers. Different revolutionary generals were quite good at military leadership, but the unique demands of fighting for or against a rebel insurrection put them off their game. However they got this dubious status, both the British and American sides had their share of questionable leadership.

Benedict Arnold

From a tactical standpoint, Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold was a worthy addition to the American cause, helping to lead the capture of Fort Ticonderoga in 1775 and helping in weighty tasks by Commander George Washington and the Continental Army, including the 1777 Battle of Saratoga. Arnold also helped develop one of the first American naval forces, sending an admittedly ragtag group of ships against the British in October 1776 on Lake Champlain. Though many of those vessels were lost, the British were so held up that they lost serious ground in the war.

But things started going sour in the spring of 1779 when Arnold began sending coded messages to British general Henry Clinton indicating his desire to abandon the cause. He nearly gave up West Point to the British in September 1780, but Arnold's contact, Maj. John André, was captured and executed by Continental forces. Arnold led a few 1781 campaigns against the Revolutionaries, then fled to Britain, where he was widely snubbed for his turncoat ways.

So, what made the name of a once-promising general shorthand for a traitor? Arnold never made his motivations completely clear, but he did ask for a considerable sum for becoming a Redcoat. He also experienced political upheaval, was passed over for promotions, had Loyalist in-laws, a wife with expensive tastes, and possible issues with a bad temper and self-esteem. However, as Washington and others would have surely told you, feeling a bit bad about yourself or your bank account aren't good reasons for betraying your country.

Charles Lee

Charles Lee may have initially seemed like a good general. Raised in Britain and sent to fight in North America in the French and Indian War of the 1759s and 1760s, Lee eventually settled in the American colonies and went rebel when the revolution began. However, while he won recognition for his command of Charleston, South Carolina, during a 1776 attack, Lee was a sore loser. He had hoped that he would be the one picked to lead the Continental Army, but when George Washington won the spot and Lee became second in command, he loudly whined about it.

Things got worse when he was captured by the British in December 1776. He was released in 1778, only to embarrass himself further at the Battle of Monmouth on June 28 of that year. While leading troops, Maj. Gen. Lee thought that the British were in the process of surrounding them and ordered a retreat. Washington, however, disagreed. The Continental Army prevailed that day, thanks to the work of seemingly everyone but Lee and the soldiers under his command.

Washington must have let Lee know as much, as a battlefield argument between the two was such a big deal that Lee was charged with insubordination and court-martialed. He was suspended for a year, spending that time moaning further about the evil Washington had done to him and getting wounded in a duel by one of Washington's defenders. Lee finally resigned in 1780 and died in Philadelphia two years later.

Thomas Conway

Skill will only take you so far, as Brig. Gen. Thomas Conway learned to his detriment. He wasn't half bad as an officer, having served in the French military since 1749 and joining the Americans in 1777. But his ego got in the way.

Perhaps part of the problem was the tendency for foreign officers to view the American military as a way to easily level up in rank. Maybe that's why it stung so much when George Washington took his time promoting Conway to major general. But other brigadier generals had been there longer, and Conway didn't exactly win friends with what sounds like an inflated sense of self-worth and frequent criticism of the less-formal ways of the Continental Army. Then, he got in with Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates, who was part of a vocal group advocating for a new commander. The group became known as the Conway Cabal. Washington wasn't exactly keen on the whole affair, though Conway never admitted to Washington that he was part of the cabal.

When Washington's ouster failed, Conway attempted to quit. The first time he tried in October 1777, the Continental Congress refused and gave him a promotion — Conway was still an experienced officer, after all. But when Conway did it again in the spring of 1778, they accepted his resignation. In July of that year, a friend of Washington's wounded Conway in a duel, and the man soon left for France. At least he had then the decency to send an apology to Washington.

Preudhomme de Borre

The French-born Preudhomme de Borre could only point to a nine-month stint as a brigadier general in the Continental Army. The experienced military man was commissioned as an American officer in December 1776, but something awkward must have happened on the voyage to the colonies, as de Borre was apparently made to leave the ship he embarked on and finish the journey on another vessel.

Things seemed to go well enough once he landed in New Hampshire and took command of his brigade. Then, summer brought serious controversy when, having captured a Loyalist, de Borre had the man hanged. George Washington wrote to de Borre on August 3, 1777, that, though the executed man had been guilty of a hanging offense, "it was a matter that did not come within the jurisdiction of martial law, and therefore the whole proceeding was irregular and illegal," not to mention apt to rile up the colonists.

De Borre stayed on, however, going on to try Maj. Thomas Mullens for insubordination and commanding brigades at Staten Island and Brandywine. But his conduct at Brandywine was scattered, with brigades ordered into incorrect positions that may have contributed to the American loss. Washington ordered an inquiry into de Borre's behavior, which prompted de Borre to tender his resignation in mid-September 1777. Then, de Borre backtracked and asked Congress for a further inquiry of his command at Brandywine. Not only did Congress decline, but its members agreed to pay for de Borre's return trip to France.

William Howe

At first, the decision to make William Howe the commander in chief of the British army in the American colonies must have seemed like a solid choice. He was a seasoned military man, earning status as a general during the French and Indian War. When he permanently assumed command in 1776, the British army enjoyed victories in battles at Long Island and Brandywine. But it was his dogged determination to squash George Washington and pursue the capture of Philadelphia (and ignore sending troops to Saratoga, which was a catalyst for the French entering the war) that allowed the rebels to ultimately emerge victorious. It was so bad that some lay the blame for Britain's embarrassing loss of its colonies at Howe's feet.

Is Howe's reputation entirely deserved? Some say that he was turned into a scapegoat, acting as a convenient target for blame that should have been shared amongst many British commanders. Yet, despite his successes, it's hard to ignore his equally serious failures. There was his inability to capture Washington after the Continental commander led a 1776 ambush of Hessian mercenaries in Trenton, New Jersey, which proved to be a pivotal moment in the war. Howe also failed to discourage and disband the Continental Congress after taking Philadelphia — instead, they simply picked up and moved to nearby Lancaster, seemingly undeterred by the presence of the British commander-in-chief so close by. While in Philadelphia, as loyalist Joseph Galloway later told Parliament, Howe allowed what seemed to be many other golden opportunities to crush the rebels slip through his fingers.

James Wilkinson

James Wilkinsononce seemed so promising. He made such an impression working for Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates that Gates asked Congress to grant Wilkinson a promotion. Yet, the then-20-year-old Wilkinson had hardly any battlefield experience and controversially skipped over more senior colonels to get his 1777 boost to brigadier general. He didn't do the rank much honor, either. After the promotion, Wilkinson soon became associated with the anti-Washington Conway Cabal. Though it's unclear if he was ever an active plotter, Wilkinson did tell Congress about the affair, implicating Gates and angering his former mentor. This nominally put him on Washington's side but contributed to his historical reputation as an untrustworthy snitch (after the war, he even spied for Spain). Perhaps feeling the heat, Wilkinson resigned in 1778.

He returned for a 1779 appointment as the army's clothier general, but Wilkinson was so lackluster in the role that Washington complained to Congress. They cut his pay, and Wilkinson resigned yet again in March 1781.

Though it occurred after the revolution, his third return and promotion to major general indicates a well-known ego. In 1799, Washington wrote to Alexander Hamilton that bumping Wilkinson up in rank "would feed his ambition, soothe his vanity, and by arresting discontent, produce the good effect you contemplate" (via "An Artist in Treason: The Extraordinary Double Life of James Wilkinson," by Andro Linklater). Otherwise, Washington noted, Wilkinson could become even more of a problem. Even without knowledge of his double-crossing, Wilkinson's revolutionary career comes across as more distracting burden than real contribution to the cause.

Matthias Alexis Roche de Fermoy

Matthias Alexis Roche de Fermoy must have been a point of confusion for other, better generals in the Continental Army. Yes, the Martinique-born de Fermoy did show up in the colonies in 1776, claiming to be a French colonel, a move that earned him a commission as a brigadier general. But his actions thereafter weren't exactly becoming of a great officer. Sure, his first few engagements went by without much upset, but when the British began to move their forces from Trenton to Princeton in January 1777, de Fermoy started to fumble. He was supposed to position his soldiers between the two cities to hold up the British, but de Fermoy took this opportunity to get too drunk to command.

In March, de Fermoy was put in charge of Fort Independence, though George Washington reportedly balked at the idea. De Fermoy abandoned the fort on July 6, 1777, and, disobeying orders, set fire to it. That made it painfully obvious to the British that the rebels there and at nearby Fort Ticonderoga, under the command of Gen. Arthur St. Clair, were retreating. By drawing British attention, de Fermoy put St. Clair's troops in danger.

Despite this, de Fermoy thought that he could still rise in rank and asked Congress to make him a major general. That didn't happen, and de Fermoy resigned in January 1778, with Congress giving him an $800 payout to return to the Caribbean, after which he disappeared from the record.

[Featured image by Pi3.124 via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 4.0]

Horatio Gates

When investigating the less-than-honorable generals of the American Revolution, there's one name that keeps popping up: Horatio Gates. On the surface, that may seem odd, as Gates was a supremely seasoned British officer. By 1769, however, he had given up his post in the British army and settled in Virginia with the help of his friend, George Washington. Eventually, he joined up with the revolutionary cause.

Gates' biggest triumph may have been the victory at Saratoga, where British Maj. Gen. John Burgoyne surrendered to him on October 17, 1777. Yet this also seems to have marked a downturn in the relationship between Gates and Washington, starting when Gates went straight to Congress with news of his victory — without first notifying Washington. Things got worse with the rise of the Conway Cabal, whose members meant to take Washington out of power and replace him with Gates. When Gates took up the leadership of the Board of War in November 1777, he was in a prime position to continue butting heads with Washington.

Then, Gates went back to the field. Commanding forces in the southern colonies, Gates attempted to face off against British soldiers in Camden, South Carolina, on August 16, 1780. The resulting battle was a disaster for the colonists. Even worse, Gates hustled off the battlefield, seemingly abandoning his troops in the middle of their retreat. He was effectively fired in October 1780 and, despite a brief reinstatement from 1782 to 1783, his reputation never really recovered.

Henry Clinton

If William Howe proved to be kind of a dud in the British general department, then surely British forces hoped that his successor would be better. But Henry Clinton, who took over as commander in chief of the British army in North America after Howe's February 1778 resignation, wasn't much better. Things were promising at first, as Clinton successfully took Charleston in 1780. But then he left the south, leaving command of the region to Gen. Charles Cornwallis.

Clinton apparently misjudged the other man, as Cornwallis attempted to take more territory in the south despite the increasingly unsteady situation of the British forces. Clinton made it worse in June 1780, proclaiming that Loyalists had to fight to earn protection, making rebels all the more ready to fight. Clinton eventually ordered Cornwallis and his men to station themselves along the Chesapeake Bay and secure a harbor for the British. Cornwallis chose Yorktown, Virginia, where his forces were besieged by the Continental Army and its supporting French forces in October 1781. Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, effectively ending the war.

Many blamed Clinton for the humiliating loss. The commander-in-chief had failed to send reinforcements in time and more broadly misjudged how to allocate troops and supplies. If he had been more bold — or just resigned as he planned to do in 1780 — perhaps Cornwallis could have held out. Even so, enough uncertainty remained that Clinton kept his post, even landing a promotion in 1793 and later becoming governor of Gibraltar.

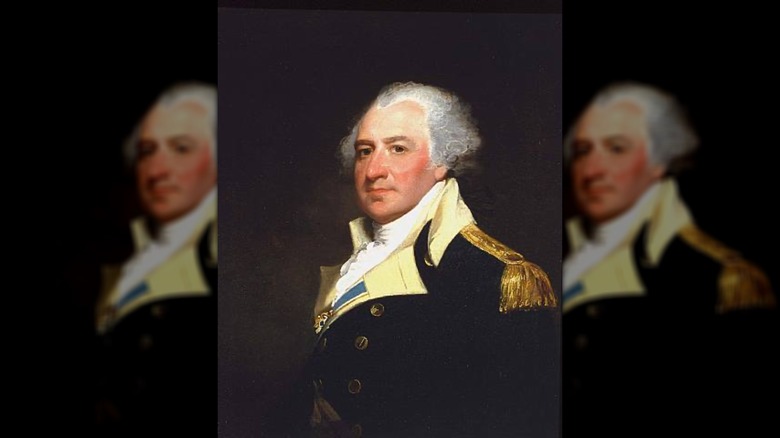

Thomas Mifflin

The winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge in Pennsylvania was notoriously awful. Continental Army forces encamped there faced serious issues including little food and poor clothing. At least George Washington stayed with the army and focused on training them. If only his quartermaster general was on the same level.

That man was merchant Thomas Mifflin, who joined the Continental Army in 1775 and was soon appointed the force's quartermaster general, as well as becoming a major general. Yet Mifflin reportedly was more interested in making a name for himself on the battlefield than managing unglamorous supply lines. He was also seemingly overwhelmed by the demands of a growing army after Congress ordered its expansion in 1777. Then, some began to accuse Mifflin of skimming off the top, holding back vital supplies and selling them for his own benefit, or at least of bungling their delivery while the soldiers at Valley Forge suffered. Embroiled in controversy — Mifflin also associated with the anti-Washington Conway Cabal — he stepped away from the post.

Nathanael Greene replaced him as the army's more efficient quartermaster general, a real sting as Mifflin was allegedly jealous of Greene's closeness to Washington. Mifflin came back to serve on the army's Board of War, but continued disputes with Washington (and a Congressional investigation into Mifflin's work) led to Mifflin resigning his commission in February 1779. Yet, perhaps thanks to powerful friends, he became president of the Continental Congress in 1783, in time to accept Washington's resignation as commander-in-chief.