The Reason Dodo Birds Went Extinct

Picture this: You're a species of ground dove that's found in only one place in the world, spending your idyllic life skipping around the island paradise you call home, where predators are few and food is plentiful. One day, strange wooden vessels start landing on the shore, carrying some peculiar-looking hairless apes who promptly proceed to cut down swaths of trees, set loose a whole bunch of animals you've never seen before, and generally disturb the peace and quiet of your habitat. As time passes, you notice that there are fewer and fewer of your kind around the island. At some point, you meet your end, too, likely violently. In a way, it's fortunate that you'll never know what comes next: For centuries after the last of your kind dies out, your entire species will become immortalized in history and popular culture as some sort of pathetic misfire by Mother Nature.

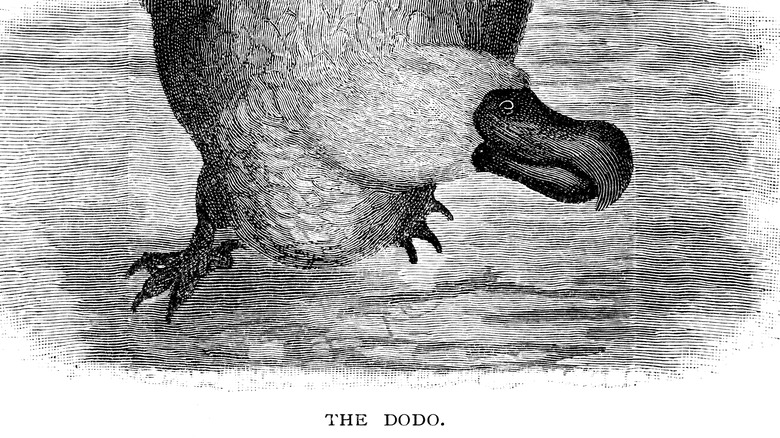

Indeed, no other species has been the victim of misinformation as severely as the dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus). It is so well-known as an evolutionary failure that chances are, you already have an unflattering picture of it in your head as you're reading this. You've probably even heard things that are unavailable (or trends no longer in fashion) described as "dead as a dodo," or someone with demonstrably poor cognition being called "dumb as a dodo." And while this flightless avian's alleged shortcomings have been blamed for its downfall, the truth is actually more tragic than that.

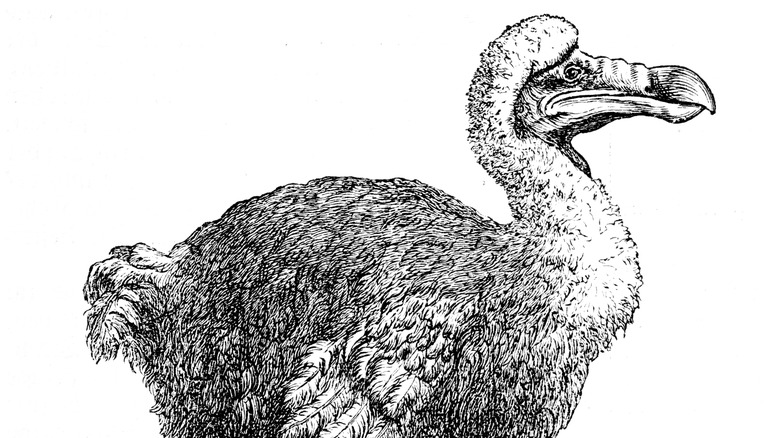

The dodo was stronger and smarter than we thought

There are many things that science got wrong about the dinosaurs, but that's understandable. After all, they've been extinct for about 66 million years, and we're learning more about them with each new discovery or reanalysis. But their descendant, the dodo bird, proved that you don't even need to be gone for more than a century for scientists to be completely way off-base about your life. Until the last decade or so, the dodo was depicted as a comically chubby, clumsy cretin, too complacent and trusting to survive its newly arrived neighbors. This image persisted due to a dearth of data from physical specimens and terribly inaccurate accounts of dodos from people who interacted with them.

However, recent research has gone a long way toward overturning the dodo's frankly undeserved reputation. In a 2016 study published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, researchers laser-scanned dodo remains — including the Port Louis Thirioux dodo, the only known complete skeleton from an individual dodo — to create 3D digital models for closer examination. They determined that the dodo's large kneecaps, wide pelvis, and sturdy leg bones meant that it was actually strong and agile enough to dart around the rocky forests of Mauritius. Meanwhile, a 2016 study in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society revealed that, based on an X-ray of a dodo skull, it likely had a sharp sense of smell and may have even been as bright as a pigeon. Not too shabby, right?

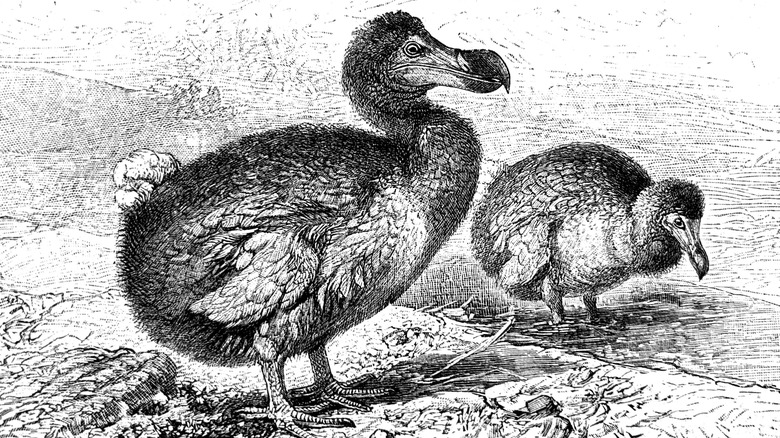

How the people of the past described and portrayed the bird

Given how different dodo birds actually were from how humanity has imagined them for the last three or so centuries, one can't help but wonder: Just how unreliable were the narrators and artists who chronicled this poor bird's existence? According to a 2006 article in Historical Biology, the writings of Dutch sailor Heyndrick Dircksz Jolinck, who wrote an account from his 1598 voyage to Mauritius, may have been the first to ever describe the dodo. Jolinck mentioned a flightless bird with wings of a comparable size to a pigeon's. Allegedly, Portuguese explorers called it a "penguin."

Illustrations dating back to 1601 highlighted the dodo's peculiar features: A round body with a hooded, dome-shaped head complementing its hooked beak, and an awkward posture. Subsequent renditions — including Roelant Savery's 1926 painting "Edward's Dodo," likely the most instantly recognizable among the dodo's now-outdated depictions — emphasized its bizarre features and seemingly vacant expression. Arguably, what really helped the "dumb-looking" dodo achieve mainstream popularity was John Tenniel's take on the bird from 1865 as one of the many curious characters in Lewis Carroll's "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland." The rendition came around two centuries after the last confirmed sighting of a live dodo. Even Carl Linnaeus, whom many recognize as the father of taxonomy, seemed to believe that the dodo was such a pathetic creature that it deserved the binomial name "Didus ineptus" ("inept dodo" or "inept simpleton") in 1766, although it thankfully didn't stick.

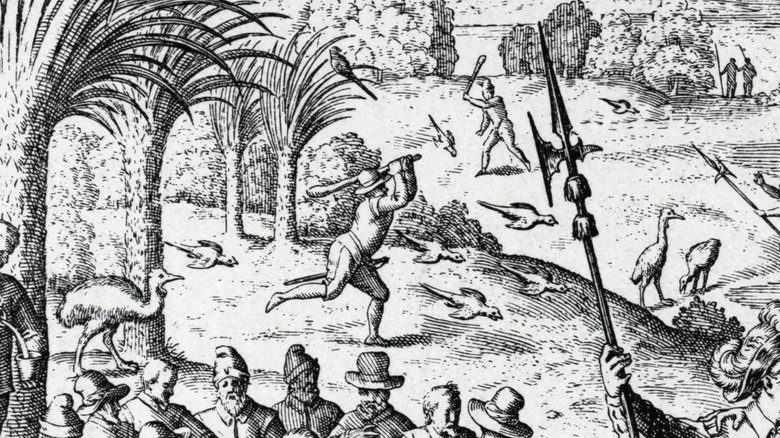

Humans probably didn't hunt the species to extinction

Early on, experts who tried to understand the disappearance of the dodo assumed (thanks in no small part to its dim-witted depiction) that it was hunted to extinction by Dutch sailors. After the arrival of European colonizers on Mauritius, it supposedly took less than a century for them to thoroughly deplete the population of this goofy-looking ground dove. To quote the 1598 journal entry published in History Biology that likely referred to the dodo: "These particular birds have a stomach so large that it could provide two men with a tasty meal and was actually the most delicious part of the bird." Subsequent accounts from the 1600s mention how fat-covered dodos were captured and brought to the ships, where starving sailors devoured them with gusto. On the other hand, numerous written accounts also attest to the dodo being a less-than-desirable meal choice. Allegedly described as hard (as well as "offensive and of no nourishment," per the BBC), journal entries published by the University of Salzburg show that some sailors even gave the dodo the unsavory name "walchvögel" ("repulsive bird" or "tasteless bird" in Dutch).

So, which one was it: Was the dodo too disgusting or too delicious? Well, hungry explorers who subsisted on nothing but hard biscuits and preserved meat for months would have loved fresh, plump poultry meat, regardless of actual taste. But all things considered, the likeliest explanation is that while dodo meat wasn't terribly unpleasant, better options existed — Mauritian pigeons and parrots were in no short supply. Thus, it's unlikely that hunters directly caused the dodo to die out.

Competition and predation helped kill off the dodo

Hunting may have contributed to the dodo bird's decline, but based on the accounts of Dutch sailors on Mauritius, these activities likely took place only near the coasts. What's more, there were too few people at any given time (less than 50, on average) for hunting to make a meaningful dent in the animal's population. Realistically, the biggest direct drivers of dodo extinction weren't the European invaders but the menagerie of menaces that tagged along with them.

Black rats somehow found their way to nearly every continent and are responsible for some of the worst invasive species disasters in history. Dutch sailors from the Age of Sail observed an abundance of the creepy, all-consuming critters on their ships, which essentially served as the vectors for the rats and helped them invade Mauritius. Given their size, it was unlikely that they preyed upon the dodos. Rather, the rats would have been fast, formidable competition when it came to food gathering, which in turn would have led to the starvation of many dodos and hatchlings.

Other animals, including crab-eating macaques, cattle, cats, goats, pigs, and deer, were introduced to the island not only by the Dutch but also by the Portuguese sailors who preceded them. Like rats, they became threats to the dodo's existence. The pinkish porcine predators, for instance, ate dodo chicks and trampled nests. Meanwhile, the picky primates could have beaten the dodos to the crabs, seeds, and fruits believed to have been part of the bird's diet.

Other factors that helped drive the species to extinction

Predation and invasion did not doom the dodo on their own. The relentless exploitation of resources on Mauritius also severely degraded the animal's habitat — a clear example of the worst ways humans have impacted nature. When Dutch sailors reached the island, they took note of the abundance of ebony trees in its rocky forests. As that type of wood was an important trade resource at the time, the Dutch mass-harvested the trees. However, the rapid, relentless tree-cutting reportedly created a glut in the European ebony market, to the point where government-mandated limits on ebony tree cutting were imposed (and subsequently disregarded) because of the sheer volume of trees the Dutch had been felling. Sadly, this, along with the increased use of Mauritian land for agricultural purposes, left the dodo populations with inadequate sources of food and shelter, to the detriment of the already defenseless birds.

Worse, the increase in anthropogenic activities and introduced species on the island came at the worst possible time: A period when the species' numbers were likely just recovering after barely making it through a terrible natural catastrophe. In 2015, researchers from the University of Amsterdam described a mass grave thousands of years old in Mare aux Songes, formerly a freshwater lake. They theorized that an extended drought forced Mauritian fauna to convene there — and their accumulated fecal matter turned it into a noxious "dodo swamp" that killed approximately 100,000 different animals "by intoxication, dehydration, trampling, and miring."

The bird likely went extinct in 1690

Judging from how swiftly the dodo bird disappeared from Dutch sailors' journals (mentions of the bird post-1620 were few and far between), its demise was drastic and swift. For the longest time, it was commonly thought that the last surviving dodos died in 1662. Recently, though, experts have noted accounts of sailors reportedly consuming dodo meat in the early 1680s. Modern estimates suggest that the dwindling dodo population had already stopped breeding by then but held on until 1690, based on hunting records from around that time.

Tragically, the dodo was eradicated before humanity collectively understood that a species could actually be eradicated. Near the end of the 1790s, Georges Cuvier stood behind the idea of species extinction being possible. By that time, the dodo had actually already been wiped out for more than a century, even though no one realized it. (Sadly, based on the number of animals that went extinct in the last 100 years, it looks like humanity still hasn't learned its lesson.)

Worse, for a brief period of time, people actually thought it never existed. Per the 1778 account of a Mr. Morel, the secretary of the Port Louis Hospital on Mauritius, locals were completely unfamiliar with the dodo, as none of them had ever seen one alive. Combined with a lack of information and surviving specimens, it became easier to believe that sailors from the 1600s had simply made up stories about the bird, which they deemed too ridiculous to be real.

The last known dodo bird specimens

The dodo bird was endemic to Mauritius, but that doesn't mean the species never made it off the island. In the early 1600s, Emperor Rudolf II kept a dodo — historians debate whether it was stuffed or alive — in his collection of curiosities in Prague, and Roelant Savery painted the reconstructed Raphus for the ruler circa 1630. Allegedly, the partial dodo beak in Prague's National Museum came from this specimen.

In 1638, English theologian Sir Hamon L'Estrange supposedly paid a London shopkeeper a penny to see a live "strange fowle" that was bigger than a turkey cock, per The Guardian. L'Estrange wrote that the "Dodo," as the owner called it, ate nutmeg-sized pebbles (gastroliths, to break down tough food in its stomach). Nearly 30 years later, a leg from a dodo somehow landed in the collection of Robert Hubert. Legend has it that the appendage came from the bird L'Estrange saw. Curiously, the Royal Society came into possession of a dodo leg — perhaps, some say, the same one Hubert had — in 1681, described as "cover'd with a reddish yellow Scale" in Nehemiah Grew's catalogue of the Society's collection.

But the most easily recognizable specimen is perhaps the Oxford dodo. The remarkably well-preserved head came from a 1656 collection. The skull — as well as some skin, a few bones, some tissue samples, and a feather — reportedly belonged to a bird that died from a shotgun blast through the neck and back of the head.

It may be gone, but its 'cousin' lives on

Interest in the dodo bird's peculiar existence peaked at a time when living specimens could no longer be found, so misinformation and misconceptions about its species diversity and genealogy proliferated. Some of the alleged varieties of the bird, based on 16th- and 17th-century chronicles, include the Nazarene dodo (a supposed three-toed species, described by German naturalist Johann Gmelin in 1789), the white dodo (which reportedly lived on Reunion Island, southwest of Mauritius), the hooded dodo (which reportedly had four toes), and the solitary dodo (from a nearby volcanic island called Rodrigues).

However, in a 2024 review published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, researchers — who combed through over 400 years' worth of scientific papers — determined that the only true dodo is Raphus cucullatus. The rest, they concluded, were either mistakenly described specimens or completely different birds. The paper also established the Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria) as the dodo's closest known (albeit also extinct) relative. Both birds belong to the Columbidae family alongside pigeons and doves.

In life, the dodo may have appeared dull to spectators, but its current closest extant (living) relative is anything but. Native to Southeast Asia, the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica) sports spectacularly colored plumage and clocks in at less than half the size of its extinct cousin. A 2002 Science study deduced that the evolutionary paths of the two avians diverged more than 40 million years ago.

The poster child for extinction

Aside from the dinosaurs, the dodo bird is perhaps the most iconic example of a dead species. As one of the first recorded instances of human-induced extinction, the dodo's grim fate is a critical milestone in science history. In the words of paleobiologist Neil Gostling (via the BBC), it's a testament to "our ability to just destroy things." But the dodo is far from the only species to go the way of the, well, dinosaurs. The passenger pigeon was driven to ruin by habitat destruction and relentless hunting, while the recently extinct Bramble Cay melomys holds the unfortunate distinction of being the first mammal to go extinct due to manmade climate change. Arguably, both of those creatures are charismatic enough to become flagship species for conservation — so why are we, as a civilization, so fixated with the dearly departed dodo?

There's no doubt that the dodo's depictions in contemporary entertainment — from children's stories to museum displays to animated movies — helped cement its reputation as the poster child for extinction. But its perennial popularity may have been due in part, interestingly enough, to the persistent misconception that it was simply too stupid to survive, yet somehow did. As American humorist Will Cuppy wrote in 1941 (via The New York Times), "You can't look like that and survive. Or can you?" Then again, perhaps Gostling summed it up best: "It's just a weird, weird bird."

Can the dodo be brought back?

The dodo bird may not be extinct forever — it's one of the many extinct animals science wants to bring back. And among the many institutions that have been vocal about wanting to resurrect the species, biotech company Colossal Biosciences is likely the most visible and, perhaps, the closest to succeeding. If the name of the company sounds familiar, it's because it made headlines in April 2025 for its "de-extinction" of the dire wolf, a Pleistocene-era predator that disappeared from the planet over 10,000 years ago, via "cloning."

The announcement was also massively controversial. In a nutshell, Colossal implanted the egg cells of surrogate dog mothers with gray wolf cells that were gene-edited to mimic characteristics of dire wolves. The approach Colossal plans to take with its dodo de-extinction project is similar: The company plans to use gene-edited chickens as surrogate mothers, injecting them with edited "primordial" genetic material from Nicobar pigeons to produce dodos (of course, after more gene editing). Indeed, in September 2025, the company claimed that its scientists successfully grew pigeon primordial germ cells. The idea of bringing back this victim of circumstance is undoubtedly fascinating, but "For what?" is a valid question. "If we can put back a large ground-dwelling fruit-eating bird, we don't know all of the consequences, but we anticipate that we will have some happy surprises," said Colossal's scientific chief Beth Shapiro (via The Guardian).

Should the dodo be brought back?

You've probably spent time thinking about what life would be like if dinosaurs never went extinct, so it's not odd at all to wonder about the repercussions of restoring recently extinct species. De-extinctionists often support resurrecting a species that used to perform a specific role in its ecosystem to justify bringing back the dead. In the case of the dodo, contemporary studies suggest that it was a key player in regrowing forests across Mauritius, its droppings serving as nutrient-rich vessels for seed dispersal. Given the island's environmental conservation woes, that's a sound reason to bring the dodo back, right?

As with any other de-extinction attempt, there are numerous ethical, practical, and logistical concerns about such an endeavor, especially considering how much the world has changed in the hundreds of years that the dodo has been gone. For starters, at our current level of technology, an extinct species cannot truly be brought back. As Colossal's Beth Shapiro explained to Scientific American, gene-editing an organism into impeccable identicality "is not really possible [...] we want to create functional versions of extinct species [and not] something that is 100 percent genetically identical."

De-extinction has its skeptics. Critics argue that such undertakings draw attention and funding away from conservation efforts for endangered species, just to restore long-dead ones that may not even thrive in today's deteriorating environment. Or, as Matt Reynolds wrote for Wired: "A few charismatic species are saved while the rest of nature burns."