The Radium Girls And Other Tragic Radiation Deaths

Everyone has heard about the radiation deaths caused by large-scale events like Hiroshima, Chernobyl, and the tragic tales of nuclear downwinders. But smaller-scale radiation deaths have often escaped notice. Obvious events like nuclear lab accidents have exposed scientists to inordinate amounts of radiation and caused indescribable damage and pain. Other, less expected backdrops such as watch factories have delivered doses of radium exposure that brought about creeping death, one excruciating symptom at a time. There are even spy stories that lend credence to the cinematic tropes of assassination via radioactive poison delivered in a cup of tea.

Crack the veneer of these horrifying deaths, and you're bound to find a lesson in the hubris of man and the terrors of tinkering with such awesome power. But before you reach it, you have to dig through a world of suffering — sometimes as collateral damage in service of taking radioactive energy to new levels, other times as a terrible accident that no one could have predicted. No matter how they came about, these lesser-known radiation deaths are a study in the terrifying effects of lethal exposure.

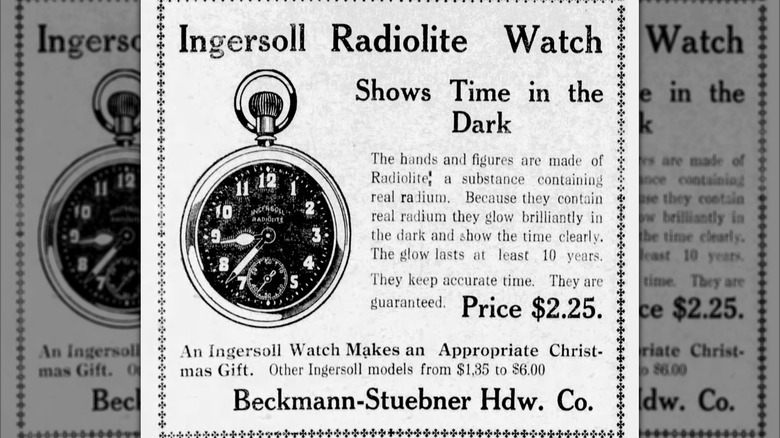

The Radium Girls

Before the deadly effects of radium were fully understood, a company called the U.S. Radium Corporation began accenting watch dials and airplane instrument faces with radium-based glow-in-the-dark paint, an innovation that aimed to help soldiers fighting overseas in World War I. To keep the fine point needed for such delicate work, the young women hired to paint the dials wetted their brushes on their tongues. Every day, they consumed poisonous radium, all the while being assured by the company that everything was perfectly safe.

Over time, the women began losing teeth and experiencing bone damage, the most notable of which was deterioration of the jawbone — a condition that came to be known as "radium jaw." Twenty-five-year-old Mollie Maggia was the first Radium Girl to die, in 1922; by 1927, more than 50 workers had died. The ongoing damage led pathologist Harrison Martland to develop a test that revealed internal radium levels in the workers, helping tie their deaths to radiation poisoning. Ultimately, five of the workers, dubbed the Radium Girls, filed a lawsuit against U.S. Radium, though the $10,000 settlements they ended up receiving were nominal at best.

The messed-up truth about the Radium Girls was exposed in a 2017 book that chronicled the tragic details of the Radium Girls and brought the plight of these workers to light once again. A 2018 film unrelated to the book gave faces and voices to the girls themselves.

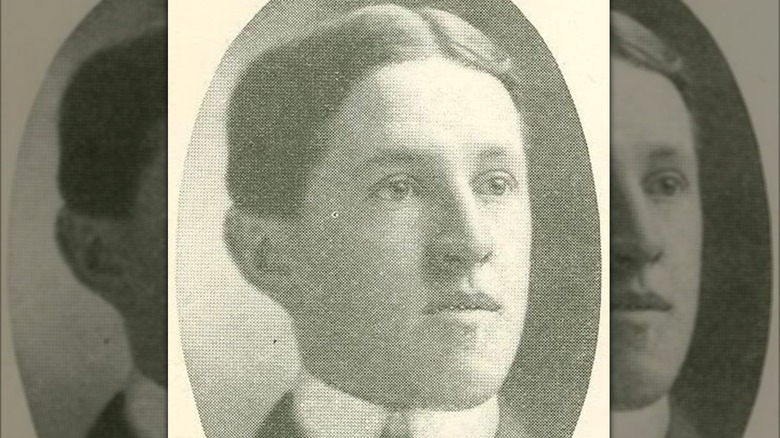

Dr. Sabin Arnold von Sochocky

It wasn't only the Radium Girls who succumbed to the effects of radioactive paint; the scientist who created the formula, Dr. Sabin Arnold von Sochocky, also ended up a victim of the substance's horrifying effects. Dr. von Sochocky believed that radium was the lighting of the future. In a 1926 document entitled "The Wonders of Radium," he was quoted as having stated that "the time will doubtless come when you will have in your own home (or someone you know will have) a room lighted entirely by radium."

As a director at the U.S. Radium Corporation, Dr. von Sochocky was convinced that radium consumed by the watch painters would eventually dissolve. He would discover that not only were the factory workers fatally impacted, but he himself was doomed, too. Having inhaled plenty of radium during his years of working with the substance, Dr. von Sochocky developed aplastic anemia, which prevented his body from producing new blood cells. A description of the side effects lists "his front teeth gone and fingers up to the second knuckle were black as the result of radium necrosis" (via Find a Grave).

Despite attempts to save his life through more than a dozen transfusions, Dr. von Sochocky died in 1928 at his New Jersey home. A newspaper story announcing his death listed him as the seventh known victim of the phosphorescent paint he'd created (via Press of Atlantic City).

Hisashi Ouchi

Nobody wants to hold the title of the world's most radioactive man, but that's the mantle worn by Hisashi Ouchi, a worker at a uranium processing plant in Tokaimura, Japan. On September 30, 1999, Ouchi was one of 49 people exposed to radiation in what was at the time the worst nuclear accident in Japan. In terms of radiation exposure, seven sieverts is considered deadly; Ouchi received 17 sieverts, more than any other victim onsite — and more than anyone else had ever received.

The fatal accident occurred when, rather than following the usual pump-based process for mixing enriched uranium in a quantity of 2.4 kg, workers mixed 16 kg manually in a stainless steel bucket. Ouchi was leaning over the tank without protective covering when the materials released a blue flash of Cerenkov radiation (via The BMJ). The chain reaction that followed released radiation for a nearly 20-hour period.

Ouchi was transported to the National Institute of Radiological Sciences, where tests revealed his white blood cell count had been reduced to practically nothing. Despite undergoing transfusions and a stem cell transplant, he couldn't be saved. During Ouchi's excruciating 83-day radiation death, he cried blood, and his skin sloughed off. He finally succumbed to his injuries on December 21, 1999.

Eben Byers

In the early days of radioactive science, physicians heralded the discovery as a cure-all that could resolve a slew of ailments. Naturally, this proved to be fatal for many early adopters, one of whom was Eben Byers. A former golf champion who'd sustained an arm injury in 1927, Byers was prescribed Radithor, a concoction of distilled water mixed with radium and mesothorium, by physician C. C. Moyar, as a healing tonic.

Once Byers felt the perceived restorative properties of Radithor, he started handing it out to friends and feeding it to his racehorses. Byers took to drinking an average of three bottles daily over the course of two years. He also believed it bolstered his love life and helped him recapture the virility of his youth, which prompted him to share the radioactive elixir with his girlfriends as well.

But the good times came to a screeching halt in 1930, when Byers began losing his teeth. The Federal Trade Commission initiated a case against Bailey Radium Laboratories, the company behind Radithor. By this time, Byers had lost most of his lower jaw and his entire upper jaw. Other bones were dissolving as well, and a hole had begun to develop in his skull.

Though Dr. Moyar defended his use of Radithor — and even claimed to drink it himself — Bailey Radium Laboratories were ordered to cease and desist in December 1931. It was too late for Byers, who died in 1932.

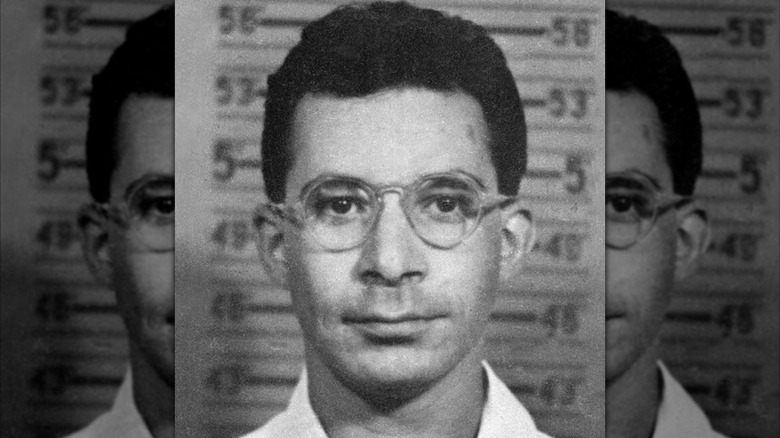

Harry Daghlian

Anyone who worked on the Manhattan Project willingly took on a risk of accidental exposure to radioactive materials. It's just part of the messed-up history of nuclear weapons. Still, it was a shock when an unexpected slip sealed the fate of physicist Harry Daghlian (above right) with a dose of radiation that was too great to survive. His willingness to put himself in a perilous situation in the name of science proved to be a fatal flaw, making him the first figure to die from lab-oriented radiation poisoning.

While testing a structure that would later come to be known as "the Demon Core," Daghlian was arranging tungsten carbide blocks around a plutonium sphere to create a deflector intended to reduce the requisite mass for taking the plutonium to the critical state. He inadvertently dropped one of the blocks onto the core, which drove the plutonium into a supercritical state and exposed the scientist to raw radiation. When he tried to knock the stray brick away, he received yet another dose.

Part of Daghlian's mortal mistake: He was working alone, defying safety protocols. Though this prevented other workers from being exposed as well, it also meant there was no one onsite to help Daghlian during the accident. After this incident, rules requiring that at least two people be on deck during experiments were instituted to enhance safety.

Despite receiving emergency medical attention, Daghlian fell into a coma and died on September 15, 1945 — 25 days after the accident.

Louis Slotin

Though some Manhattan Project scientists attempted to prevent the use of the atomic bomb, others stayed on after the war ended to continue their work. Louis Slotin was one of these figures, tasked with assembling the core used in atomic bombs. The precarious task, referred to as "tickling the dragon's tail," involved arranging two beryllium hemispheres like a shell around the core itself to monitor the rate of criticality. Closing the hemispheres entirely would result in an ionizing blast, a pulse-pounding risk that Slotin's danger-loving nature seemed perfectly suited for.

During a May 1946 experiment, Slotkin was separating the two hemispheres with a screwdriver when the tool slipped, closing the halves of the beryllium shell. A blue flash and a release of intense radiation resulted. Slotkin pulled the hemispheres apart again to stop the reaction, receiving what would later be determined to be 2,100 rem (a measure of biological harm caused by radiation) in the process. Ordinarily, 500 rem is considered lethal; Sloktin's exposure was more than four times higher.

Though he'd shielded his coworkers from exposure of their own, an act for which he was honored as a hero, Slotkin couldn't survive; he died nine days later. As the second figure in the Manhattan Project to die from radiation poisoning, his death resulted in improved safety protocols for nuclear labs.

Marie Curie

The most recognized figure in the world of radioactive studies is Madame Marie Curie, the woman who discovered the underlying nature of radiation. Her death due to radiation poisoning may be the least surprising, but it might also be one of the most symbolic — a woman willing to risk her own life to advance human knowledge in monumental ways. Not only was she a pioneer in the fields of chemistry and nuclear science, she was also a lauded female scientist in a time when science wasn't exactly welcoming of women.

Curie's curiosity regarding radiation led her to choose the burgeoning field as the subject of her thesis. Her studies of uranium revealed that it was more than just the mineral that caused radioactivity in the ore in which it occurred. As a result, she and her husband, Pierre, identified polonium, a substance 400 times more radioactive than uranium. Curie's further studies led to the discovery of radium, even more radioactive than polonium and the element Curie's name is most associated with.

While her achievements won her two Nobel Prizes, her regular exposure to toxic materials led to ongoing bouts of radiation poisoning. Curie ultimately died in 1934 from aplastic anemia, likely a result of her radiation exposure. Her papers remain radioactive enough to require storage in lead boxes, demonstrating how Curie's work in radioactivity lives on in unexpected ways.

Alexander Litvinenko

Tales of murderous spy craft often include disposing of one's enemies via poison, though it sounds more like a literary device than a real-life practice. But when human rights activist Alexander Litvinenko, a former KGB agent with suspected ties to MI6, succumbed to radiation poisoning in 2006, it became clear just how dark the espionage business can be. Oddly, in the world of surreptitious meetings and devious deceptions, it was a cup of tea suspected to contain a deadly dose of polonium-210 that may have been Litvinenko's undoing.

Supposedly, Litvinenko was digging into links between Spain and the Russian mafia when he met two former agents for tea at London's Millennium Hotel. Shortly after the meeting, Litvinenko became ill and ended up in Barnet General Hospital, where his situation became even graver.

During an interview conducted while he was undergoing treatment, Litvinenko revealed he'd been investigating the death of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya. The former spy was also a critic of the Putin regime, which led some to connect clues that traced his poisoning back to the Kremlin — a suspicion that the European Court of Human Rights concluded to be true. In another twist befitting a former spy, Litvinenko assisted greatly with the investigation of his own poisoning while still alive. Ever the intelligence officer, he was able to help authorities piece together the happenings leading up to the incident before he died on November 23, 2006.

Douglas Crofut

The cardinal rule of working with radioactive materials is, of course, to handle them with grave caution. Douglas Crofut, a professional radiographer, should have been well versed in this practice. Unfortunately, his lack of care led to his fully avoidable death, spurred on by the influence of alcohol and the all-around absence of safety precautions surrounding his daily work.

As an oilfield worker who used X-ray tech to evaluate welds in pipelines, Crofut used machinery that contained either iridium or cobalt — both highly radioactive materials. A habitual criminal with 16 arrests and a penchant for heavy drinking, Crofut was suspected in December 1980 of stealing a radiography machine similar to what he would have used for his job. The machine was returned anonymously on January 5, 1981; two weeks later, Crofut showed up at a hospital with extensive radiation burns. Based on the positioning of the burns, authorities suspected Crofut had carried a radioactive capsule around in his shirt pocket.

Over his prolonged period of illness, Crofut's flesh slowly deteriorated, with the radiation burn reaching his organs as it created incredible pain. He was treated over a six-month period, until his death in late July 1981 — the first radiation poisoning death in the U.S. since the Manhattan Project nearly 40 years prior.

Yasser Arafat

One of the highest-profile figures to be suspected of dying from radiation poisoning was Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. Arafat was a prominent figure in the effort to attain statehood for Palestine during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. After an unexpected illness in 2004 that caused grave intestinal distress and subsequent organ failure, Arafat died suddenly in Percy Hospital near Paris, France.

Despite investigating what may have initiated the illness, no cause could be determined; the official cause was listed as a massive stroke, and no autopsy was performed. But in 2011, forensic specialists discovered that stains on Arafat's belongings contained higher than normal amounts of polonium-210 (via Science Direct). His body was exhumed in 2012 for further testing. As a report for Forensic Science International detailed, "Significantly higher (up to 20 times) activities of 210Po and lead-210 (210Pb) were found in the ribs, iliac crest and sternum specimens compared to reference samples from the literature."

Arafat's widow proclaimed his death a murder based on the results of the exhumation, though medical professionals pointed to the fact that Arafat never lost his hair, a side effect of polonium poisoning. Though it was never proven indisputably, the levels of polonium found in Arafat's bones as well as in the soil where he was buried were 18 times higher than normal, if not more.

Cecil Kelley

In 1958, Los Alamos chemical operator Cecil Kelley was mixing a vat of hazardous materials, a brew that included plutonium residue. His associates were outside the vat room when they witnessed a blue flash; soon after, Kelley appeared, dazed and crying out about the burning sensation that had overtaken him.

The amount of time that Kelley was exposed to this radiation? A mere 200 microseconds. But that was all it took for him to lose muscle coordination and feel as if his flesh were on fire. Associates thought the accident might have been chemical in nature, so Kelley was taken to a shower and attended to by medical personnel within minutes. It was only when the monitoring team noticed high gamma readings from the tank room where Kelley had been working that staff realized what had really happened.

The rapid sequence of symptoms that followed led Kelley through a quick yet agonizing descent. Tests revealed he'd been run through with 3,600 rad, a combination of neutron and gamma ray exposure that was more than three times above the fatal exposure limit of 1,000 rad. Other reports list the exposure received by his heart as closer to 12,000 rad. Within six hours, Kelley's lymphocytes were gone; by the 24-hour mark, his bone marrow had stopped producing new blood cells.

About 35 hours after the accident, Kelley died. Tests performed on his body after his death were the beginnings of the Los Alamos Human Tissue Analysis Program.

The Boy from Mexico City

One of the most unfortunate stories of death by radiation occurred in 1962, when a boy from Mexico City brought home a radioactive capsule, with tragic results. Naturally, the boy had no way of knowing what he had in his pocket, or the destruction it would visit on his household. Within a few days, it had become a full-blown family tragedy.

Details are murky regarding where the boy found the capsule or how it was released from its protective lead casing. The boy had the unprotected capsule in his pocket for several days before his mother discovered it and placed it in the kitchen. Though the mother noticed the family's drinking glasses were turning black, there was no way for her to know that it was an indicator of radioactivity in the house. What is known about the incident: The capsule contained 5-Ci cobalt-60, a substance used in X-rays. A report from the family's doctor listed several deaths, including that of a pregnant family member. Determining who was exposed and by how much was difficult, since everyone had gone about their lives without realizing what they were being exposed to.

From the time the boy brought the capsule home in March to the time the capsule was finally removed on July 22, two family members had died, including the boy himself. It wasn't until August 13 that radiation poisoning was suspected. By October 15, two more family members were dead.