The Messed Up Truth About The Radium Girls

History is filled with episodes that prove mankind is just sort of making everything up as it goes. There's no shortage of things that can kill us or do horrible, terrible things to our soft and squishy bodies, and every time we think we know about them all, it turns out there's something else lurking around the corner.

And sometimes, it's disguised as something awesome. Need proof? Look no further than the Radium Girls.

Yes, that radium. Today, the Royal Society of Chemistry says there's really only one use for radium — targeted cancer treatments, because it's so good at killing cells. It was first discovered in 1898 by Marie and Pierre Curie, after they extracted a single milligram from ten tons of a uranium ore called pitchblende. And it was pretty darn cool. It glowed, and seriously, how exciting is that? Unfortunately, it was also deadly — as the so-called Radium Girls would find out.

It was a great job... before the Radium Girls began to disintegrate

It didn't take long for entrepreneurs to see the potential value in the luminescent properties of radium. Just a few years after it was discovered, William J. Hammer mixed it with zinc sulfide and created a paint. While he didn't patent the invention, Tiffany & Company did. According to the Oak Ridge Associated Universities, it was wildly popular in Europe first, and the people who worked with it would glow as they walked through the streets at night.

It wasn't until 1914 that radium-based luminescent paint started to be produced in the US. By 1921, the main manufacturer had already expanded a few times and moved, changing their name to the United States Radium Corporation and patenting the name "Undark" for their paint. Other companies started popping up as well, using named like "Luna" and "Marvelite" for their paints.

They weren't just making paints, they were doing the painting, too. According to NPR, US Radium hired scores of girls and young women — as young as just 11-years-old — to paint watch dials with the glow-in-the-dark, radium-based paint. As if just working with the paint wasn't bad enough, they were also encouraged to put the brush between their lips and twirl it into a point. It was the best way to get truly precise numbers and brush strokes, but with each lick of the brush, they were swallowing radium.

Many girls loved to paint themselves with radium

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there were no safety precautions put in place for working with this material that we now know is deadly. According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, it wasn't long before US Radium was even getting military contracts to paint watches and instrument panels, and that meant more work for the girls. That should have been a good thing, but it absolutely wasn't.

The workers, of course, didn't know this — they were assured the paint was harmless, so they often just had a little fun with it, too. The Atlantic says it was common for the girls to paint their fingernails and teeth with it, because who wouldn't love to glow in the dark? Later — much later — when Harvard physiologist Cecil Drinker did a study to see just how much radium the girls were actually covered in, he found something terrible. Workers would be so covered with the paint and radium dust used elsewhere in the plant that they would glow completely. The dust got everywhere: it wasn't just on their hands and faces, it was on their clothes, their undergarments, and even on their skin beneath their clothes.

And all along, they were assured it was safe.

Have you had your daily dose of radium?

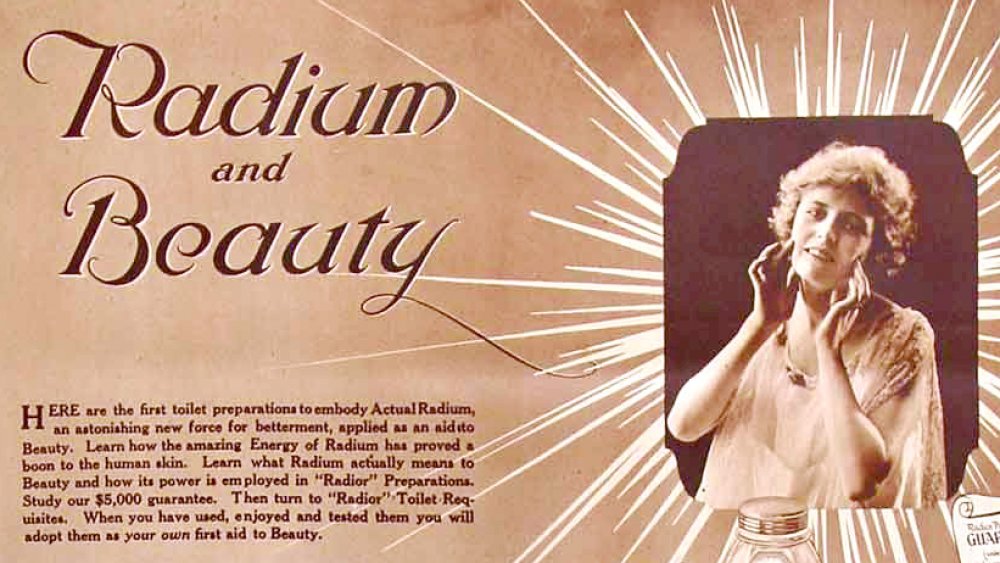

It's worth noting that this wasn't just a case of a corrupt company telling their employees their working conditions were safe — at least, not at first. Radium was thought to be super healthy: it was often marketed as a cure-all, and there was a shocking number of products that hit the market just full of radium. And, you know, death.

It really started in earnest in 1904, when LD Gardner began marketing a health water he called "Liquid Sunshine." According to the New York Historical Society, belief in radium's healthy benefits was rooted in a massive misstep in logic. Early experiments using radium to kill cancer cells had been a success, and if it could kill cancer, surely, it could kill whatever else was ailing you ... right? Real doctors started experimenting with it as a cure for things like tuberculosis and lupus, while the quacks started marketing their own so-called cures for everything from acne and baldness to impotence and insanity.

People drank radium water and brushed their teeth with radium toothpaste, and radium cosmetics were all the rage. Children played with toys painted with radium, and performers on the New York stage danced and twirled in costumes that glowed. Radium was in such high demand that prices soared. By 1915, a single gram cost what would be around $1.9 million in today's money, and that means many of the products didn't contain real radium — fortunately for consumers.

The Radium Girls' sickness came slowly

When the workers started getting sick, they got sick very slowly. Today, we know exactly what was happening to them. Calcium, says the National Institute of Child Health and Development, works like this: bones constantly strengthen themselves by replacing old calcium with new calcium. When there's an imbalance of more calcium going out than coming in, that's when bones get weak and start breaking. But according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, the human body isn't great at telling the difference between radium and calcium. Radium gets absorbed into the bones just like calcium does, and when that happens, the rot starts.

Writer and historian Kate Moore documented the cases of the Radium Girls (via The Spectator) and found that there were a whole host of symptoms. Some started suffering from chronic exhaustion. For many, it started with their teeth — one by one, those teeth would start to decay and rot. When they were removed, their gums wouldn't heal. In some cases, the jaw would just simply disintegrate at the dentist's touch. Bad breath was common. Skin became so delicate that the slightest touch would tear open wounds. Ulcers formed for some, and those that were pregnant bore stillborn babies.

It was a variety of symptoms, and when the girls started looking for recompense, that became a huge problem. Attorneys for US Radium argued that with all of these different ailments, they couldn't possibly have the same underlying cause. But... they did.

When it got bad, it got really bad for the Radium Girls

According to author and historian Kate Moore (via NPR), there's no way to tell just how many dial painters there were, and how many died terrible, painful deaths. After the symptoms came the deaths, and they were always awful and usually long, drawn-out illnesses punctuated by doctor's visits where they were assured the pain in their bones was something like arthritis.

Many — those that we know about, at least — were typically in their 20s when they became really and truly ill. They were young women like Margaret Looney, who grew so weak her fiance would pull her around in a wagon. Bones crumbled, limbs were amputated, spines were crushed under their own weight. The girls became anemic, bedridden, unable to eat. Wisconsin PRX reports that their bones were so weakened their internal structure resembled a honeycomb. The pain was constant, and in the late 1930s, enough were dead or dying that they got national attention. The New York Historical Society says that US Radium first tried to blame the girls' illness on an outbreak of syphilis, and it was years before the girls got their day in court. By that time, many testified from the same beds they would eventually die in, and they became known as "the society of the living dead."

Companies definitely tried to cover it up

Companies didn't just try to blame the terrible illnesses on other causes, they absolutely took an active role in trying to cover up the truth.

Take the case of Margaret Looney. She was one of the first to die from the radiation, and when NPR spoke to her niece, Darlene Halm, she said she could very vividly remember her family talking about her aunt's tendency to bring vials of the paint home with her. She was one of a family of 10, and would cover herself — and her siblings — with the radium paint. It took about six years for her to reach the end, and when she did finally collapse, she was at work when it happened. She was taken to a company hospital, and her family was told she had been quarantined for diphtheria. She died in the hospital, just 24-years-old.

Looney's family didn't believe the story — especially considering the company had refused to let them see her or her body. The Looney family insisted on an autopsy with their own doctor present, but by the time that doctor got there, the autopsy was already done. Her death was brushed under the carpet, and it would come out later that doctors had been hired to find out what was wrong with the painters as early as 1925. Those doctors had assured Looney — and her coworkers — that she was perfectly healthy, and skipped over the part about all the radiation.

The Radium Girls faced an uphill battle for compensation

The lawsuits started in the mid-1920s, but it was shockingly difficult to even find an attorney to take the girls' case. Why? When five painters sued US Radium in 1927, they were told, for starters, that they had passed the 2-year statute of limitations for complaints. They didn't testify until 1928, and months of delays prompted the newspapers to pick up the story. Those women accepted an out-of-court settlement (via The Library of Congress), and when Ottawa-based painters from The Radium Dial Company tried to sue in 1935, they ran into the same problems. They, however, refused to settle.

It was another two years before their case was heard in court, and by then Catherine Wolfe Donohue, one of the lead plaintiffs, had already collapsed at a previous hearing. She gave her testimony from her sickbed, and photos were plastered all over the country's newspapers. They won their case, but it had to be a hollow victory — Radium Dial appealed, and Donohue lived just long enough to know that their first appeal was denied.

According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, there's a heartbreaking footnote to this. The girls were often saddled with massive medical bills, and by the time medical bills and legal fees were paid, the radium girls got next to nothing for their pain and suffering. Even those that won an annual stipend didn't get much — they didn't live long enough to collect.

The 'society of the living dead' was shunned

There was another byproduct of the trial: the girls who were a part of the so-called "society of the living dead" weren't aided by their community — they were shunned.

Writer and historian Kate Moore says (via NPR) that in spite of the fact that these were young mothers, wives, and girls who were dying, the communities they lived in just didn't want to acknowledge what was happening to them. After talking to locals and reading countless documents — including personal letters to and from the girls — she found that it was an overwhelming belief that they just needed to be quiet about the whole thing.

Why? The jobs paid very well at a time when work was scarce. It was the Great Depression, after all, and locals were afraid that if the Radium Girls won their case, that work would go away — deadly or not.

The Radium Girls who survived were plagued with health issues

Not all of the Radium Girls died young, but those who did survive struggled with predictably awful health issues. Take Mae Keane, who died in 2014 at the admirable age of 107. She was one of the last, says NPR, and she was hired on as a dial painter in 1924. Fortunately for her, though, she didn't like it. When she was taught how to point the brush with her lips, she was revolted by the taste of the radium paint. Keane said she only worked there for a few days when she was called into the office and asked if she would like to quit. She said yes.

She was one of several hundred who did survive (it's impossible to tell how many Radium Girls there were, and how many lived, although at least one other — Mabel Williams — survived past her 100th birthday). Over the course of her life, she suffered from chronic health problems, including ones that sound eerily similar to those suffered by the girls who died: bad teeth and migraines. She also survived two diagnoses of cancer, and while she says she can't definitely blame her health issues 100 percent on the radium, she did say she wished she had met the boss who asked her to quit just one more time. "I often wish I had met him after to thank him, because I would have been like the rest of them."

From Radium Dial to Luminous Processes

As it turns out, dying women and some guilty verdicts couldn't stop the radium paint industry. Catherine Donohue weighed less than 60 pounds when she died, before Radium Dial finished appealing their case before the Supreme Court. In 1934, their president, Joseph Kelly, was kicked out of the company, but NPR says that wasn't the last company he opened. Radium Dial went out of business, but Kelly simply moved to a building down the road, and reopened as Luminous Processes. He hired a work force from among the girls who had been put out of work when Radium Dial closed, and he kept them painting ... for a long, long time.

It wasn't until 1976 that Luminous was fined by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Why? They had been found to be exposing their workers to radiation levels 1,666 times higher than regulations allowed. Assets were shuffled, Luminous closed, and the lawsuits that continued into the 1980s went largely unpaid.

A shocking oversight? Definitely. According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, the cases brought by the dial painters helped establish safety guidelines for later companies where working with radiation was the norm — including the Manhattan Project. They also helped push through legislation that allows workers to file suit for compensation if suffering from an occupational illness, a small consolation to the families of dial painters who were exposed to hazardous working conditions long after their employers knew the dangers.

The Radium Girls had to be buried in lead-lined coffins

The Radium Girls weren't just sick, they were very literally radioactive. Mollie Maggia was exhumed in 1927, in the hopes that her bones would give still-living Radium Girls the evidence they needed to win in court. According to Popular Science, her coffin was lifted out of the ground, and her body? It glowed. That wasn't entirely surprising, considering her bones were found to be highly radioactive — and considering radium's half-life is 1,600 years, they're not going to stop glowing any time soon.

Ottawa, Illinois was known as Death City throughout the 1930s, says The Los Angeles Times, and in 1987, the documentary Radium City tried to show just how long-lasting the effects were, in a very graphic way: when one man headed into the Catholic cemetery that is the final resting place of many of the Radium Girls, the Geiger counter he carried goes nuts — their remains, six feet down, are still radioactive.

With some of the girls, precautions were taken. Margaret Looney and Catherine Donohue were buried in lead-lined coffins, says Wisconsin PXR. And yes, devotees of radium-based health products are just as radioactive. Industrialist and golfer Eben Byers was the poster child for a drink called RadiThor, and drank several bottles of it a day. Holes formed in his skull, his jaw fell off, and his bones began to crumble. He died in 1932, and was so radioactive that he too was buried in a lead-lined coffin (via The Conversation).

The building continued to poison others

If you think the legacy of the Radium Girls ended when the companies using radium-based paint closed, you'd be sorely mistaken. According to The Atlantic, after Radium Dial closed (and essentially re-opened down the street as Luminous Processes), the building was converted into a meatpacking plant. Does this seem like a terrible idea? It does, and it was. After the meatpacking plant closed, it became a farmer's co-op, and it was finally torn down in 1968. The rubble was used as fill around the city of Ottawa. Another bad idea? Absolutely. The building that housed Luminous didn't fare much better, and for years after that plant closed it, too, was used for storing meat.

Eventually, 16 separate sites around Ottawa would be classified as Superfund sites.

NPR Illinois says that many have been cleaned up, but as of 2018, there was at least one site — a 17-acre plot of land on the Fox River — that still remained a highly radioactive and terrifying legacy of the Radium Girls.