The Truth About Wild West Gunfights

Shootouts in the Wild West are, in the popular imagination, full of stereotypes. Many movie-goers have seen Clint Eastwood as a lone drifter coming to mete out justice through the barrel of a gun or an all star team of gunslingers defending a village ravaged by bandits. The Wild West, and in particular its shootouts, are engraved into popular culture.

But are these shootouts true?

The violence of Wild West shootouts has many surprising historic kernels of truth. Where it differs is that these affairs of quick death were even more violent than imagined, and there was often little distinction between good guys and bad guys. Many of these gunfights involved brutal individuals who sometimes worked on the side of the law and sometimes did not. In most cases, drunkenness and gambling were involved. In some cases, the historical events reveal outstanding bravery, which seem to outweigh what has even been fictionalized.

Let's take a look at some of the history's most notable gunfights and gunslingers, so as to better understand the truth about Wild West gunfights.

Captain Davis slaughters a gang of desperados single-handedly

A remarkable Wild West shootout that has been largely lost to history occurred in the Sierra Nevada in 1854. According to VFW Magazine, Jonathan Davis, a former army officer, honorary captain, and veteran of the Mexican War had moved to gold-rush-era California to find his fortune. On December 19, he and two companions were outside the Sacramento area when they were suddenly barraged with bullets by 14 bandits.

One of Davis' companions was instantly killed and the other mortally wounded. Davis chose to stick it out and fight. He must have taken cover upon which he drew out his two Colt revolvers and methodically began picking off the gang one by one. Seven went down until Davis ran out of ammunition. At this point, four of the bandits came after him with knives and cutlasses. Davis, using his Bowie knife, engaged them in close combat, mortally wounding three and cutting off the nose of another. The remaining bandits fled the scene. As for Davis, he sustained two minor wounds. His clothes suffered more with multiple bullet holes.

This episode would seem to break the boundaries of fact except, according to True West Magazine and VFW Magazine, the events were corroborated by miners nearby who witnessed the whole episode. Davis reportedly said, "I did only what hundreds of others might have done under similar circumstances."

The gunslinger of Frisco

One Old West gunfight that seems made for the silver screen is the so-called Frisco Shootout that occurred in Lower Frisco, now Reserve, N.M., in December 1884. According to D.H. Figueredo in his book, Revolvers, Vaqueros, and Caballeros, a Texan cowboy named Charlie McCarty was terrorizing the town either by taking target practice at various buildings or harassing Mexicans in a local saloon. Either way, a local justice did not act to arrest McCarty.

At this point, the 19-year old Elfego Baca, a Mexican who bristled at the Texan's discrimination, decided he was going to stand up to McCarty. He personally arrested him. However, after doing so he was surrounded by a number of McCarty's cowboy friends. Fearing for his life, Baca shot one cowboy in the knee before fleeing to an adobe house. There he holed up as 80 cowboys besieged him in a gunfight that lasted for a day and a half, with over 4,000 bullets shot at Baca. Baca managed to kill eight and wound four before a sheriff from a neighboring town arrived and broke it up. Baca was tried for murder but acquitted after it was shown that over 400 bullets had been fired into the door of the adobe that Baca hid in. He became known as the "man of nine lives." He went on to serve as a United States marshal and other prominent public positions. In the 1950s, Walt Disney produced a series based on his adventures.

Wild Bill Hickok duels Davis Tutt in a quickdraw

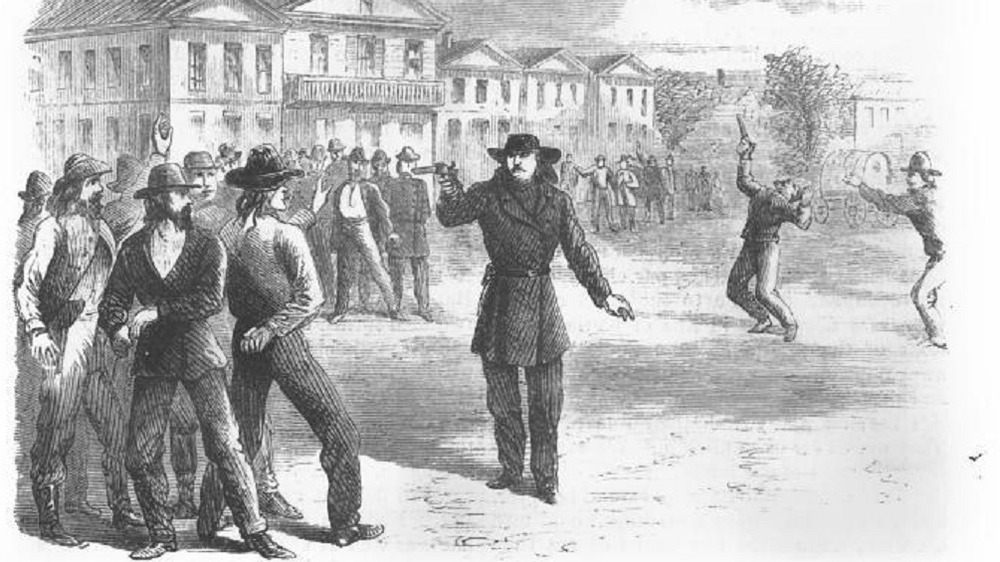

James Butler "Wild Bill" Hickok is synonymous with western gunslingers. One of his first duels, and the first one-on-one quickdraw duel according to Tom Clavin, author of Wild Bill, occurred in July 1865 when Hickok faced off against the gambler Davis K. Tutt in Springfield, Mo. Both men had been friends, but Hickok had fallen into Tutt's debt from gambling. They fast became enemies. According to the city of Springfield, Tutt took a gold watch from Hickok as collateral and began wearing it in public to humiliate him. Tutt rejected Hickok's efforts to negotiate for the watch.

Finally, on July 21, at about 6 p.m., Hickok found Tutt in the town square wearing his watch. Hickok holstered one of his two Colt navy pistols and said, "Don't you come across here with that watch." At 75 yards, both men stared at one another and turned sideways. In a few seconds, Tutt went for his gun. Hickok drew his out simultaneously. Shots rang across the square. When the smoke cleared, Tutt said, "Boys, I'm killed." He staggered back with a chest wound and collapsed.

This duel cemented Hickok's reputation as an icon of Old West lore.

Aces and eights: Wild Bill's last hand

Wild Bill Hickok's reputation was such that according to American Myths, Legends, and Tall Tales, he was hired as a deputy U.S. Marshal and served for several years. However, in 1871 his life took a downward turn when, as marshal of Abilene, Kan., he accidentally killed his deputy in a shootout. He left law enforcement and bounced around, even trying to (and failing) perform in Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show. He eventually found himself in Deadwood in the Dakota territory, where he prospected for gold by day and gambled and drank at night. Invariably, Hickok would seat himself with his back to the wall. However, on the night of Aug. 2, 1876, there was only one chair available, and that seat faced toward the wall. It proved to be Hickok's undoing since a man named Jack McCall, who had badly lost to Hickok in cards the night before, went up to the veteran gunslinger and shot him in the head.

The hand Hickok was holding, two aces and two eights, was known thereafter as the "Dead Man's Hand."

Gettin' outta Dodge

Dodge City, Kan., has notoriety as once being a penultimate frontier town in the Old West. According to Smithsonian Magazine, it was founded in 1872 to take advantage of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe railway center for buffalo hides and later cattle coming up from Texas. It earned such a reputation of violent lawlessness that the much later saying, "Gettin' Outta Dodge" became engraved in the American lexicon.

One of the most notorious incidents in Dodge involved a shootout at the Long Branch Saloon between former buffalo hunter Levi Richardson and 19-year old professional gambler "Cock-eyed" Frank Loving, who had a lazy eye. There are several variations of their quarrel. According to James Reasoner in Draw: The Greatest Gunfights of the American West, both men were interested in the same dance hall girl. However, according to the Ford County Historical Society, the woman in question was actually Loving's wife. Either way, in March 1879, the two had an altercation with Richardson striking Loving. He promised to "blow the guts out of that cock-eyed son of a b****."

Richardson's opportunity came on April 5, 1879. The Ford County Historical Society reports that Richardson gave his personal papers to an acquaintance and then visited the Long Branch Saloon, one of Loving's haunts. Richardson planted himself by a pot-bellied stove and waited. At about 8:30 that evening Loving came in. While reports from the witnesses vary, both men got to arguing and then drew their guns.

Frank Loving's luck runs out

Levi Richardson followed Frank Loving around the saloon, and, after some heated words, he opened fire at his enemy. Loving and Richardson ended up dodging and shooting around a billiard table at close quarters. The sheriff, whose office was close by, arrived quickly. By the time the law broke them up, they found Richardson shot through the chest and arm — he collapsed dead. Loving had miraculously suffered only an injury to his hand. No other person was injured.

According to the Ford County Historical Society, Loving was released by Dodge City authorities who viewed the Richardson murder as an act of self-defense. The Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters notes that by 1882 Loving had relocated to Trinidad, Colo., where he continued gambling. It is unclear if his wife joined him. It was there that he met former Dodge City denizen Jack Allen, a former deputy marshal and gambler. On April 16, the two came into conflict over gambling loans. A melee followed in Allen's establishment, the Imperial Saloon, with 16 shots fired and no injuries. Loving may have been blessing his good fortune the next day when he went to George Hammond's Hardware Store. However, while Loving was emptying the cylinder of his revolver, Allen burst in and shot Loving to death. The town was dubbed "Turbulent Trinidad" in the press.

The shootout at the Oriental Saloon

Aside from Dodge City, another iconic Old West town is Tombstone, Ariz. According to Smithsonian Magazine, Tombstone was founded in 1877 by Ed Schieffelin, who was prospecting in southeast Arizona's Dragoon Mountains. Soldiers told Schieffelin that "he'd find nothing there but his own tombstone." But Schieffelin found silver instead, and by 1880, a town named Tombstone was booming.

Tombstone became renowned for its lawlessness. It sported 20 saloons and at least a dozen gambling dens. It was also known for sudden violence. One example of this was a shootout which, according to the Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters, occurred on Feb. 25, 1881, when Luke Short and Charles Storms got into an argument over a card game at the Oriental Saloon, with Short as the house dealer. Jeff Guinn notes in his book, The Last Gunfight, that the famous Bat Masterson, a Dodge City veteran who was also dealing in the saloon, broke up the fight. He walked the drunken Storms back to his hotel. However, Storms returned to the saloon where he found Short outside. He waved his gun at him. Short in response drew his own pistol and cooly killed Storms with a bullet in the heart. Short was cleared of any criminal charges. He and Masterson soon left Tombstone.

The violence at the Oriental was a mere prelude to the most famous shootout in Tombstone of them all at the O.K. Corral.

Trouble is brewing in Tombstone

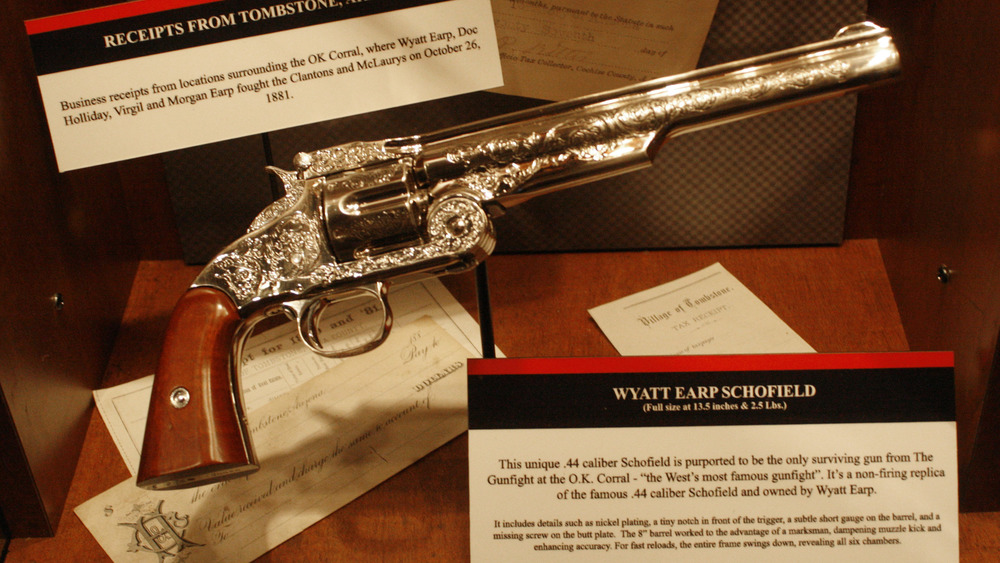

The showdown at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Ariz., is the most emblematic of Old West gunfights. The incident, which according to National Geographic, occurred on Oct. 26, 1881, has been traditionally seen as a clear case of good guys versus bad guys. In this case, Marshal Wyatt Earp, his brothers, and friend Doc Holliday were fighting the nefarious gang of "cowboys," which included Ike and Billy Clanton and Tom and Frank McLaury.

After the town's silver rush, Tombstone grew quickly, and with it two feuding factions developed. The first was led by the Earps and their friend Doc Holliday, who was an ex-dentist turned professional gambler. According to the O.K. Corral Historic Complex, Earp's faction was supported by the business classes that included the mayor. The second faction, the "cowboys," were ranchers such as the Clantons and McLaurys, who often supplemented their living through cattle rustling. They had the support of the county sheriff, Johnny Behan. All had various interests in mining, cattle, and businesses in town. The McLaurys first collided with the Earps when the brothers tracked stolen mules to their ranch. Later, Virgil Earp, as town marshal, disarmed and arrested Ike Clanton for violating Tombstone's ordinance prohibiting carrying weapons in the town.

The shootout at the O.K. Corral

According to National Geographic, the ordinance against firearms in Tombstone was galling to the cowboy faction since they were accustomed to freely carrying their firearms. The result was that Ike Clanton gathered a group of five cowboys, including the McLaurys, and purposefully defied the law. According to the O.K. Corral Historic Complex, a night of fighting and gambling brewed trouble on Oct. 26, 1881.

Marshal Virgil Earp asked Sheriff Johnny Behan for his help in disarming the cowboys. Behan, however, either could not or did not do it, nor could he prevent the Earp brothers and Doc Holliday from pursuing the Clanton-McLaury gang, who had planted themselves in a lot behind the Old Kindersley Corral. The two groups squared off.

It is unclear who fired first, but the fight was over in half a minute. Three of the five cowboys were dead. Of the Earps, all survived but were injured except for Wyatt Earp. Ike Clanton later accused the Earps of shooting unarmed men, but after it was shown that both sides were armed, the case was thrown out. Still, there were repercussions for the Earps. On Dec. 28, 1881, Virgil Earp was shot by unknown assailants and seriously injured. Then the next March, Morgan Earp was murdered. This set off a vendetta by Wyatt Earp and Holliday, who ended up killing four more cowboys. Earp and Holliday left for California in 1882. Behan's girlfriend, Josephine Marcus, also joined Earp in California.

Bankrobbers build a sense of community

Sometimes in Old West shootouts whole communities got involved. By 1892 it seemed that the violence of the Old West had largely passed. However, according to the Dalton Defenders and Coffeeville Museum in Coffeyville, Kan., a gang of five consisting of Grat, Bob, and Emmet Dalton, as well as Dick Broadwell and Bill Powers, planned an audacious robbery to hold up two banks simultaneously.

On the morning of Oct. 5, 1892, the "Dalton Gang" split up. Three entered the Condon Bank and two went to the First National Bank. At the Condon Bank, the bank robbers were told that the vault was timed and would not open until 9:30 a.m. Being that it was 9:20, they waited. This was a critical mistake, since word rustled through the town that a bank robbery was underway. Citizens rushed into Isham Hardware for guns and ammunition. In the shootout that followed, four of the Dalton Gang were killed in addition to three Coffeyville residents and a U.S. marshal. Only Emmet Dalton survived, despite sustaining 23 gunshots. Emmet, after serving 14 years in prison, received a pardon after rehabilitating himself. He became, according to the IMDB, a screenwriter in the early days of Hollywood.

The Cherokee Courtroom Shootout

In the Old West, Native American tribes had their own justice systems. This did not prevent Americans from interfering when they viewed their interests at stake. In 1872, according to Tahlequah Daily Press, in the Goingsnake district in Oklahoma, a Cherokee named Zeke Proctor shot a white man named Jim Kesterson because Kesterson had abandoned his wife (Proctor's sister) and children to live with another Cherokee woman named Polly Beck. The Times Record says that Proctor accidentally killed Beck when she tried to intervene. Proctor was to be tried in a Cherokee court, and Kesterson fretted that he would be let off. He lobbied the American government to arrest Proctor if he was acquitted.

According to the U.S. Marshals Service, a posse of ten was organized by two deputy marshals. They headed to a schoolhouse where the trial was being heard. The Times Record noted that most of this posse was formed by Cherokees from Beck's family. The Marshals Service reports that as the posse rode into the clearing before the schoolhouse, several Cherokee emerged from the building and began shooting. However, the Cherokee account claimed that the shootings occurred inside. Eight of the posse were killed. For the Cherokee, three were killed and six wounded. The shootout was the largest single killing of U.S. marshals in American history and became known as the Goingsnake Massacre.

The Cherokee court ultimately acquitted Proctor and the U.S. government accepted the verdict.

Mysterious Dave Mather

One of the most enigmatic gunslingers of the Old West was "Mysterious" Dave Mather. According to Same Lowe's Speaking Ill of the Dead: Jerks in New Mexico History, Mather was born in Connecticut but by the 1870s had moved out west joining Bat Masterson. He soon earned the nickname "Mysterious" for his silence. Sometimes Mather was an outlaw and other times a lawman. In either case he always seemed to shoot first.

Mather first came to prominence in Las Vegas, N.M., in the 1870s taking part in some illegal activities, befriending Doc Holliday. He then became a deputy U.S. marshal despite being suspected of robbing stagecoaches. He took part in multiple gunfights, according to the Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters.

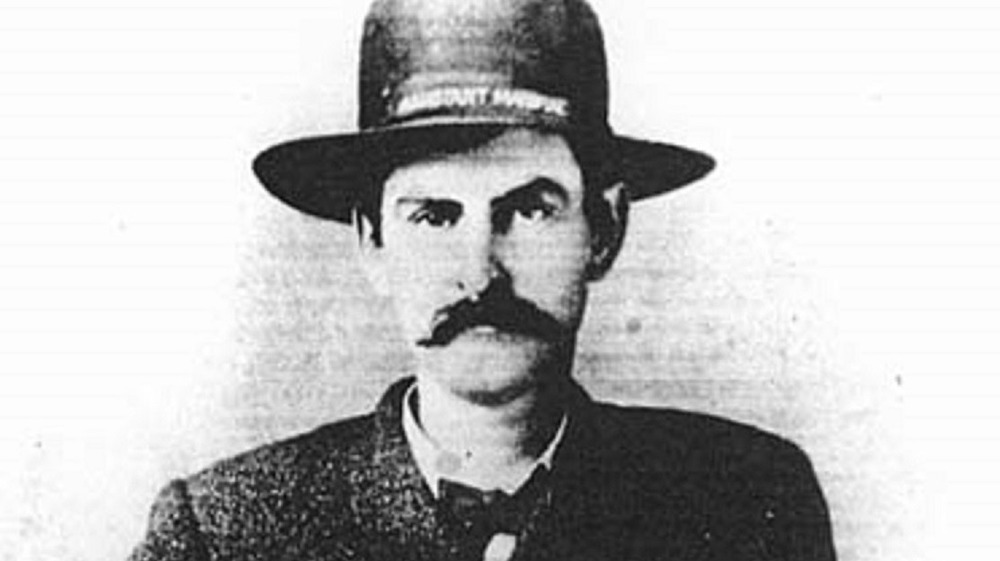

In 1883, Mather moved to Dodge City, where he got involved in politics and developed a grudge against Tom Nixon who replaced him as the city's assistant marshal. On July 18, 1884, Nixon was arrested for shooting at Mather at the Opera House where Mather ran a saloon. A few days later on July 21, while Nixon was standing at the corner by the Opera House, Mather appeared with his Colt and whispered, "Tom. Oh, Tom." Before Nixon could defend himself Mather shot him. Nixon collapsed, and Mather shot him three more times. Mather was acquitted of murder since, according to Age of the Gunfighter, the jury did not view Mather as the aggressor. Mather soon left Dodge City, and after a couple of more gunfights, Mysterious Dave, mysteriously vanished.