The Untold Story Of Elizabeth Packard's Wrongful Confinement

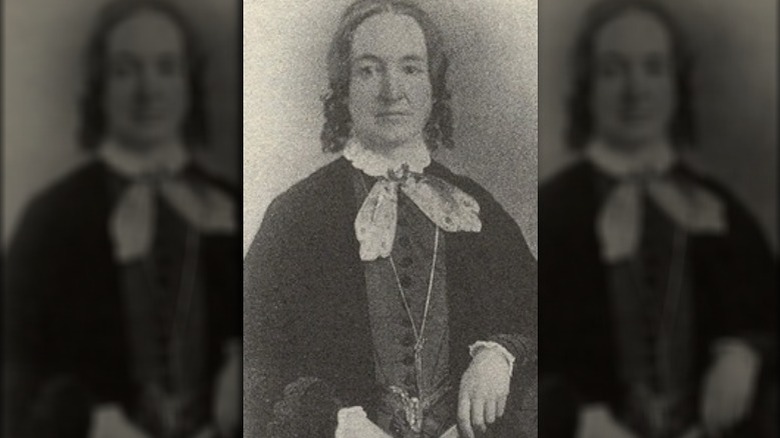

Elizabeth Packard didn't set out to be a social reformer, but after she was committed to a psychiatric hospital against her will by her husband, she worked to try to make sure that other women wouldn't suffer similar fates. Her sanity was called into question just because she disagreed with her husband on a number of issues, including religion, and at the psychiatric hospital Packard found a number of other women who had been similarly forcefully committed.

At the time in the state of Illinois, people had the right to have a trial if they were to be involuntarily committed. Unfortunately, this right didn't extend to wives, so if a husband was displeased with his wife for any reason, it was remarkably easy to simply declare his wife insane and ship her off to the hospital. And this treatment certainly wasn't limited to wives across the country. Often, the label of "insanity" was applied to any one that rejected the status quo.

But Packard didn't end up languishing in the psychiatric hospital. She not only managed to escape the clutches of the hospital, but the clutches of her husband as well. At the end of the day, Packard definitely ended up being the one to have the last laugh. But unfortunately, wrongful confinement in the United States persists even in the 21st century. This is the untold story of Elizabeth Packard's wrongful confinement.

Elizabeth Packard's early life

Elizabeth Packard was born Betsey Parsons Ware in Ware, Massachusetts on December 28, 1816, to Lucy Parsons Ware and Reverend Samuel Ware. Owlcation writes that although her parents originally named her Betsey, she changed her name to Elizabeth during her teenage years. Packard's father was a Calvinist minister and he made sure that all of his children, including his daughter, received the finest education possible. As a result, Packard was enrolled in Amherst Female Seminary and before long, "the instructors admitted she was the best scholar in their school."

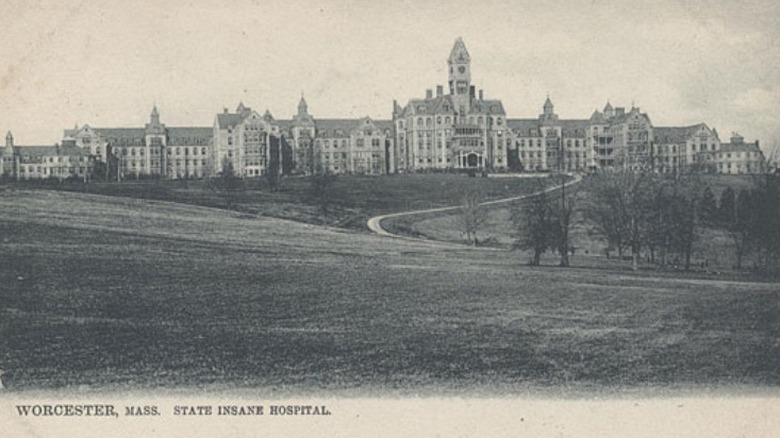

After graduating, Packard became a teacher. However, she fell ill during the 1835 winter holidays, suffering from headaches and feeling delirious, or "brain fever." Although she was seen by doctors who treated her with emetics, purges, and bleeding, her condition persisted. Believing that her condition was caused by the mental stress she was under, Packard's father checked her into Worcester State Asylum for several weeks, according to "Mrs. Packard on Dependency" by Hendrik Hartog.

According to "Fashion and Fetishism," Packard's condition ended up being attributed to her corset being "laced too light" combined with "too much mental effort" due to her job. Although it's highly unlikely that Packard's corset could result in mental illness, tightlacing was in fashion from roughly the 1830s to the 1850s, so it's possible that the physical problems she faced were associated with tightlacing. Tightlacing often resulted in faintness due to the restricted breathing as well as "poor digestion."

Marriage to Theophilus Packard

On May 21, 1839, Elizabeth married Theophilus Packard, who was 13 years older than her and had known her since she was a child. Theophilus was also a Calvinist minister, and according to Owlcation, had been raised strictly in accordance with the Calvinist faith. Her father arranged the marriage for her "as a practical and convenient way of providing for Elizabeth."

In "Elizabeth Packard: A Noble Fight," Linda V. Carlisle writes that Elizabeth decided to marry Theophilus because "she believed he was a good man who could help her become a more 'perfect person in Christ Jesus' estimation." And according to "Mrs. Packard on Dependency," "for the better part of two decades Theophilus and Elizabeth lived together in apparent harmony in western Massachusetts." In the mid-1850s, the family decided to move west and after traveling through Ohio and Iowa, they ended up settling in Manteno, Illinois in 1858.

Together, they had a total of six children. However, by the time they moved to Illinois the marriage was starting to fall apart.

Elizabeth Packard is deemed insane

Despite her Calvinist upbringing, Elizabeth Packard found herself intrigued by modern religious movements such as spiritualism, and she saw no contradiction between her Calvinist beliefs and her interest in other religions. And according to "The Letters of a Victorian Madwoman" by Andrew M. Sheffield, in 1859, "Packard [also] defended John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and reportedly outraged her Illinois neighbors." Hartog writes that at one point, during the fall of 1859, Elizabeth started openly talking about her ideas during her presentations at an adult Sunday School class in church. At that point, "parishioners began to pressure her husband to have her committed into the state insane asylum."

According to "Mrs. Packard's Revenge," after Theophilus unsuccessfully tried to get Elizabeth to withdraw from the Bible class and stop sharing her religious insights with their children, which included a conversation Elizabeth had with her dead mother during a séance, Theophilus decided that Elizabeth was insane, saying, "Never before had she so persistently refused my will or wishes. She seems strangely determined to have her own way, and it must be that she is insane."

Elizabeth was worried about her husband's suggestions that she was ill, so she consulted an attorney, who assured her that "she could not be committed without a jury trial." The final straw for both Elizabeth and Theophilus was when she interrupted her husband's sermon during church and stated that she was going to "the Methodist church across the street."

The first psychiatric hospital in Illinois

When the Jacksonville Asylum opened in 1851, it was known as the Illinois State Asylum and Hospital for the Insane. According to CARLI, when the psychiatric hospital was opened, Illinois passed a law that "required a public hearing for anyone who was going to be committed against his or her will." This is why the attorney Elizabeth Packard consulted insisted that she couldn't be committed without any sort of hearing.

Meanwhile, according to "Mrs. Packard's Revenge," Theophilus was already trying to get a court order of commitment but was unable to convince the judge of Elizabeth's insanity. However, the Illinois law has an exception; if a husband or father wants to commit his wife or daughter, he needs "neither hearing nor consent." All that was needed "was the permission of the asylum superintendent" and one doctor who agreed with the diagnosis. It was under this prerogative that Theophilus had Elizabeth committed.

Having tried to take Elizabeth to the asylum "quietly and properly" and failed, Theophilus resorted to an abduction.

Elizabeth Packard was sent to Jacksonville Asylum

Before having his wife abducted, Theophilus Packard arranged for a doctor to visit his wife under the guise of being a sewing machine salesman. According to The Atlantic, Elizabeth Packard reportedly confided in the "doctor-salesman" and told him "about her husband's extreme religious ideas and his belief that she was a lunatic." The doctor agreed for various reasons, including the fact that she "refus[ed] to shake his hand and the fact that she was above the age of 40."

According to Elizabeth's own account of the incident, it amounted to a "legal kidnapping." Early in the morning, Theophilus, two doctors, and a sheriff came to Elizabeth's bedroom door. "I hastily locked my door, and proceeded with the greatest dispatch to dress myself. But before I had hardly commenced, my husband forced an entrance into my room through the window with an axe!"

Still in a state of undress, Elizabeth lept into her bed to shield her nudity while the men approached her. "Each doctor felt my pulse, and without asking a single question both pronounced me insane." Thus, in the summer of 1860, Elizabeth Packard was committed to Jacksonville Asylum.

Three years at the asylum

Elizabeth Packard spent a total of three years at the Jacksonville Asylum. According to "Mrs. Packard on Dependency," during her time there she was monitored by Dr. Andrew McFarland, whom she claimed knew she was sane, "but depended on men like her husband for his business."

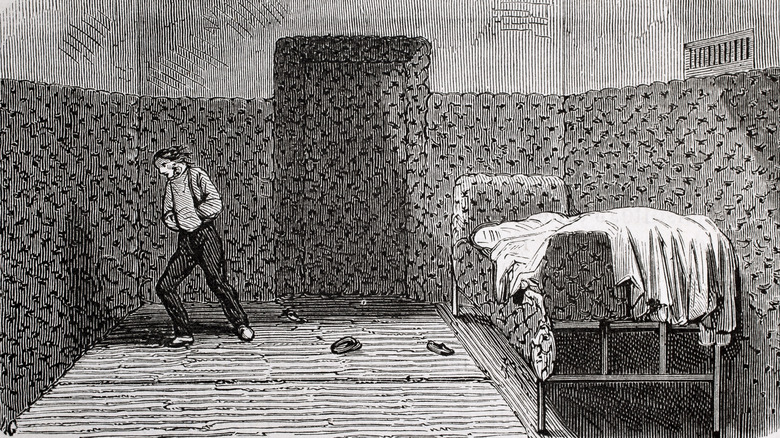

Owlcation writes that at first, Packard was put in a room by herself and had "all she needed to keep herself clean and healthy." But after a few sessions with Dr. McFarland, she was moved to another ward where "the violent and seriously ill patients were kept." Packard claimed that McFarland "had sexual designs on her" as well, so it's possible that she was moved not for resisting her husband's whims, but McFarland's. At the ward, Packard was not only attacked and harassed daily, but she witnessed first-hand how people were physically and mentally abused by the psychiatric hospital. Using any scrap of paper she could find, Packard started writing down her thoughts and experiences. According to Time Magazine, many of the people in the asylum "were also sane, but had been at the asylum for years."

After three years, the institution informed her husband that they couldn't keep Packard anymore. And upon informing Packard that she was being returned to him, she "fought unsuccessfully to stay" in the asylum just to avoid going back.

Elizabeth Packard's release

Elizabeth Packard's eldest son, also named Theophilus, was old enough to advocate her release and take full responsibility for her. As a result, Elizabeth was released in 1863 "with a letter from the Asylum stating that she was incurably insane," according to the University of Illinois. But upon being released in the fall of 1863, Elizabeth was sent back to her husband, who promptly imprisoned his wife once more in the nursery of their home, going so far as "nailing the windows shut." He also "made plans to recommit her."

Elizabeth knew that time was running out, so she desperately managed to pass a note through her window to a passing stranger. The note was addressed to Elizabeth's friend, who after being informed of her situation, appealed to Judge Charles Starr. A writ of habeas corpus, which reports unlawful detention, was made in Elizabeth's name and as a result Theophilus was required to bring her to the judge's chambers on January 12, 1864.

Owlcation writes that when Theophilus Sr. once more contended that his wife was insane and that he had legitimate reason to keep her imprisoned, the judge decided that he should have to prove this in court.

Suing for sanity

The jury trial lasted five days in 1864, from January 13th to the 18th, during which her husband insisted that Elizabeth Packard was insane because she "disagreed with him on religious and money matters." As a result, according to "Mrs. Packard on Dependency," the trial ended up becoming concerned with the question of "whether rejection of Calvinism could be evidence of insanity." Meanwhile, various witnesses came forward to testify about Elizabeth's sanity.

According to Elizabeth Packard's autobiography of the events, Theophilus also claimed that her mother was "an insane woman, and several of her relatives have been insane; and, therefore, Mrs. Packard's insanity is hereditary, consequently, she is hopelessly insane." He also had Dr. McFarland there to confirm these statements. Meanwhile, Elizabeth contended that "it is my own God given right to superintend my own thoughts." After just seven minutes of deliberation, the jury gave their verdict that Elizabeth was "SANE." But although she ended up winning the trial, before the jury gave their verdict Theophilus had packed everything up, including their children, and moved back to western Massachusetts.

Elizabeth ended up returning to her father's home. Her father reached out to Theophilus demanding for Elizabeth's clothes to be returned, which they were, but Theophilus was incredibly strict about letting his wife see their children. She was only allowed to see them sparingly and only when Theophilus was also present.

The Anti-Insane Asylum Society

Having witnessed first-hand the horrific nature of asylums at the time, Elizabeth Packard formed the Anti-Insane Asylum Society. According to the Oxford History Review, the organization was able to pressure Illinois into passing a bill in 1867 known as the "Bill for the Protection of Personal Liberty." This bill not only made it a right for residents of Illinois to have a public hearing if they were accused of insanity, but also "required that all patients then resident in the Illinois asylum had a right to test their sanity via jury trial. Within 90 days after Packard's bill became law, more than 50 trials were held," according to "Mrs. Packard's Revenge."

Packard also authored a bill that would have secured postal privileges for institutionalized people across the country, but it ended up being unsuccessful. Packard "campaigned tirelessly" for people in psychiatric hospitals, traveling to over 30 states "in her crusade to reform commitment laws." Unfortunately, the Anti-Insane Asylum Society never became a widespread movement. However, the Anti-Insane Asylum Society was also able to help get laws passed in Iowa and Massachusetts as well, "requiring a jury trial prior to any involuntary commitments into asylums," according to "Mrs. Packard on Dependency."

In addition to advocating for people in psychiatric hospitals, Packard fought to reform marriage laws and The New York Times writes that she was instrumental in helping pass a law in Illinois "that for the first time gave married women separate legal ownership of their wages."

Elizabeth Packard's life after the trial

Elizabeth Packard also went on to publish several books, including "Modern Persecution, or Married Woman's Liabilities" and "The Prison's Hidden Life, or Insane Asylums Unveiled," which did well and allowed her to live comfortably. And according to Museum of the Mind, Elizabeth was even able to get her children back "after legislation she had fought for was passed, which allowed married women equal rights to marital property and custody of children." Unfortunately, it took until the 1870s to get her children back.

However, Elizabeth ultimately ended up on top compared to her husband. Not only was she reunited with her children, but Elizabeth noted that Theophilus ended up "homeless, penniless, and childless; while I [had] a home of my own, property, and the children." Theophilus ended up passing away in 1885, and although Elizabeth never returned to him, they also never ended up getting a divorce.

Because of Elizabeth Packard, there was also a seven-month long legislative inquest into the management of the asylum where she was held. As a result of the investigation, Dr. McFarland's professional reputation was damaged, although he continued to speak out against public trials of insanity, considering them to be "unnecessary and harmful." Elizabeth Packard also outlived McFarland, who died from suicide in 1891.

Elizabeth Packard passed away on July 25, 1897. A Chicago obituary described her as "the reformer of insane asylum methods."

Wrongful confinement in USA

Unfortunately, Elizabeth Packard was neither the first nor the last person to be wrongfully confined in the United States. And although white women like Packard called themselves "slaves of the marriage union," people of color, especially women of color, were particularly vulnerable to wrongful and involuntary confinement even after actual slavery was abolished. "Married, single, and widowed women" from "all social class and ethnicity" could find themselves involuntarily confined.

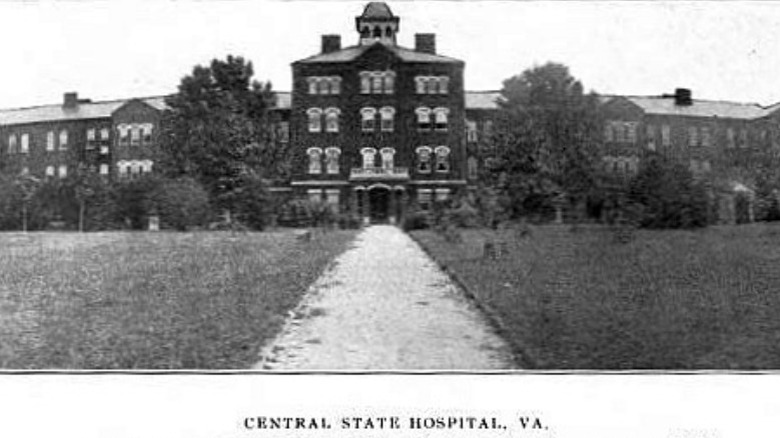

Several race-specific asylums were built across the United States. Hiawatha Asylum, for example, is where Native people from across the United States were wrongfully confined when they showed a rejection of colonialism. And according to The Washington Post, Virginia created an all-Black state asylum, known as the Central Lunatic Asylum, that "really worked just to re-enslave the people who were there."

Wrongful confinement continues into the 21st century. Kamilah Brock was involuntarily committed in a psychiatric ward for eight days in 2015 after trying to get her car back from the NYPD, who arrested her for taking her hands off the wheel at a red traffic light. In 2018, Nicolas Carter, a staff writer for Cards Against Humanity, was involuntarily confined in a psychiatric hospital over a weekend after speaking out against hate speech at work. Even when people do actually have a mental illness or a disability, the conditions in these facilities aren't much better than in Elizabeth Packard's time. And people with disabilities, especially people of color, "are systematically and routinely deprived of their rights."