The US Government's Secret Mustard Gas Experiments Explained

In World War I, the German forces used a chemical warfare agent that resulted in thousands of enemy casualties. The agent was mustard gas, also known as the "King of Battle Gasses," and caused blisters, temporary blindness, and death to those exposed (via Science History.) The use of mustard gas in WWI prompted the U.S. military to conduct secret experiments during World War II to prepare for the possibility of chemical warfare from enemy nations.

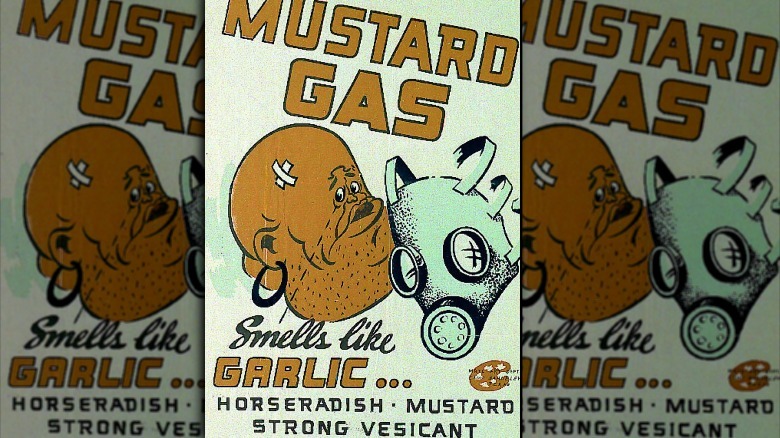

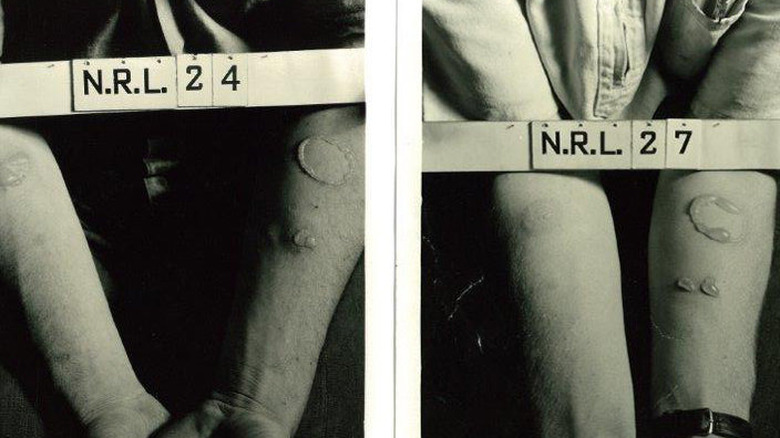

Mustard gas, or sulfur mustard, is a blistering agent and a powerful irritant that has immediate effects upon exposure. It has a yellowish-brown color and may smell like garlic, mustard, or horseradish. The U.S. government conducted secret mustard gas experiments on thousands of American soldiers. Not only that, but the experiments were race-based as scientists wanted to know if the agent has different effects on varying skin colors, per Cambridge.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the secret experiments were declassified in 1993, and since then, investigations have been done in order to understand the reasoning behind the experiment and to compensate the survivors and families of victims who were experimented on.

The mustard gas experiments and its test subjects

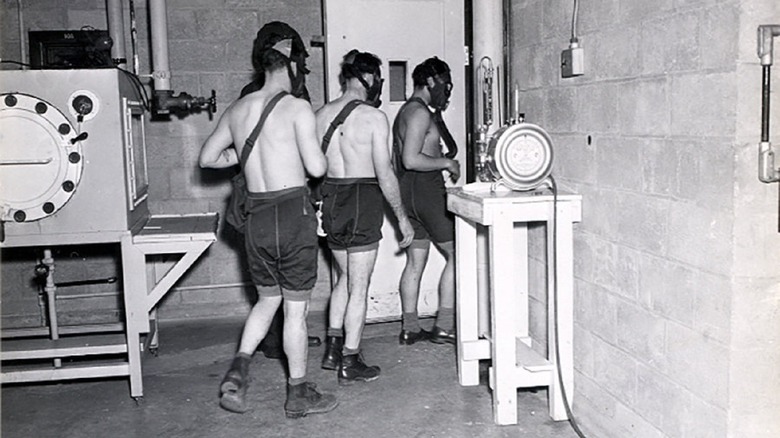

The test subjects of the mustard gas experiments were those serving their country. However, they did not volunteer themselves; rather, they were volunteered by their own officers, according to Nature. In other instances, they were given the "assignment" to be part of the experiment. Those who took part had to keep what they would go through a secret or face military prison time or dishonorable discharge (via NPR.) As the experiment was top secret, even the military records of those who took part had no trace whatsoever of what they had to go through.

The mustard gas experiments were held in Panama. One of the test subjects, Army soldier Rollins Edwards, recounted his experience (via Smithsonian Magazine.) "It felt like you were on fire," he said. He was put inside a wooden gas chamber together with other soldiers and when the mustard gas was released, screams and cries immediately echoed through the chamber. "And finally they opened the door and let us out, and the guys were just, they were in bad shape," he said.

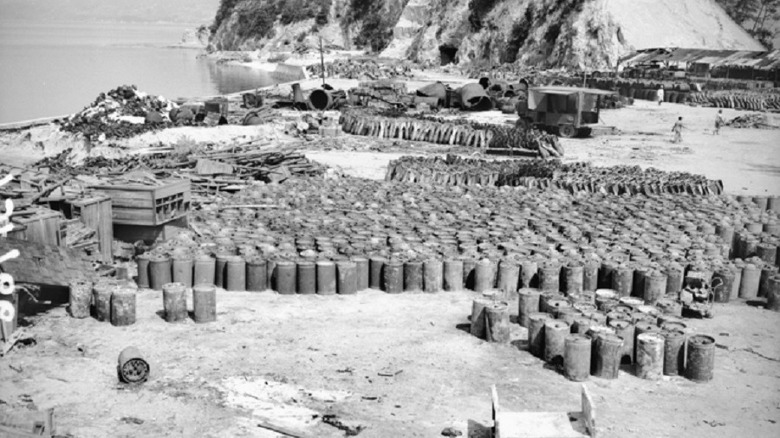

Per the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, one of the goals was to come up with ointments, protective gear, and other equipment to protect American troops in case of chemical warfare. 60,000 soldiers were subjected to mustard gas in varying degrees (a drop on the skin or other areas of the body), and out of those, 4,000 were subjected to full-body exposure.

The search for the ideal chemical soldier

The mustard gas experiment's test subjects came from different races and ethnicities — Caucasians, Asian-Americans, Latinos, African-Americans, and Native Americans. According to Nature, researchers hypothesized that mustard gas would have differing effects based on skin color, with those of a particular race having more resistance to mustard gas than others.

Per an NPR report, White men were used as the control group in the experiment, with their reactions to mustard gas seen as the benchmark for the "normal" reaction. The results were then compared to the outcome of the experiments on the minority soldiers. There were three types of tests done during the experiments: patch tests were done by dropping liquid mustard gas on the skin, chamber tests entailed men being locked up in chambers and exposed to mustard gas, and field tests had subjects placed in a combat setting outdoors while being exposed to mustard gas.

Those who were part of the experiments developed health conditions throughout the years, with reports of respiratory problems, skin issues, and even cancer, among other medical issues (via Smithsonian Magazine.)

The aftermath of the experiments

Since the experiments were declassified, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has been working on identifying those who were part of the experiment to offer health benefits and disability compensation. This is not as easy as it sounds, however, as most test subjects don't have proof that they ever participated in the mustard gas experiments. The experiment wasn't recorded on their records, and they can only offer their word on what they experienced.

Harry Bollinger, a former Navy recruit who was part of the experiment, said that he had a difficult time getting what is due him from the VA as he had no records of proof to show (via NPR.) He received countless rejection letters, and by the time the VA acknowledged his participation in the experiment, he had lost interest and said he was "disgusted." "That's going to be on my tombstone. U.S. Navy, Guinea Pig," he stated.

In 2015, NPR was able to locate about 40 living experiment participants, and most of them had the same experience as Bollinger — denials and rejection letters from the VA. Some of them chose to forgo their benefits out of dissatisfaction and frustration. As of 2015, the VA has only contacted 610 out of the thousands of test subjects.