What History Books Got Wrong About The Great Depression

Close to a century later, we still look at the Great Depression as one of the worst economic periods in modern history, if not the outright worst. Unemployment reached unprecedented highs, people in many parts of the world — and not just the United States — were reduced to abject poverty, and the decadent, free-spending Roaring Twenties were all but a memory at that point in history. And it all started in the fall of 1929 as the U.S. stock market experienced a crash unlike none other that had been seen before it. Or did it?

Spoiler alert — that's among the many less-than-accurate details history books, especially the older ones, will tell you about the Great Depression. While there is a grain of truth to these retellings of what happened before, during, and immediately after this historic crisis, they oftentimes don't tell the whole story. As you'll find out in a bit, saying that the Depression started on Black Thursday (or Black Tuesday, five days later) and ended when the Americans sent troops overseas to fight in World War II oversimplifies things by a great deal. So with that in mind, let's look at some ways the history books got it wrong when looking back on the Great Depression.

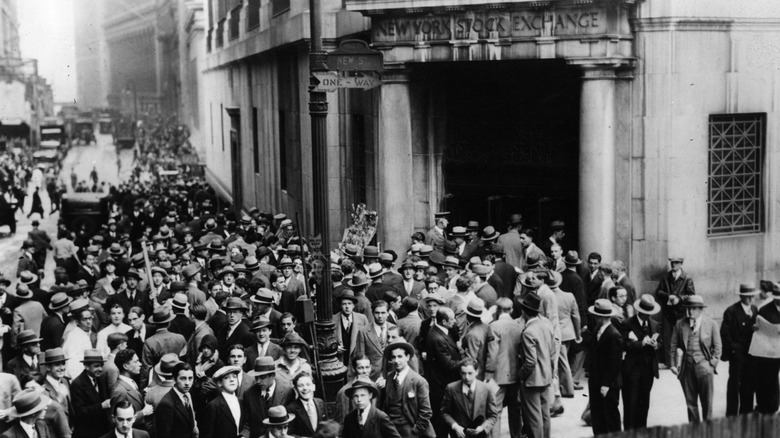

These factors, and not the Wall Street crash, may have triggered the Great Depression

It isn't just the history books that cite the stock market crash of 1929 as the one event that triggered the Great Depression. Pop culture also references the crash on many an occasion, and we can understand why. The average person has at least a basic understanding of stock market crashes, so it's not surprising this event gets most of the blame. However, there were other reasons why the recession that followed the Wall Street crash turned into the Great Depression in a matter of years.

Disregarding the advice of more than a thousand economists (via Investopedia), President Herbert Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in June 1930, which taxed imports to the United States by an additional 20% or so. It was hoped that this act would protect the American farming industry from foreign competitors, but it backfired when dozens of countries responded by imposing higher taxes on U.S. products. Due to the Smoot-Hawley act, international trade declined by a whopping 66 percent for the five-year period between 1929 and 1934. As for the U.S. unemployment rate, which was at around 9% before the act was passed, that jumped to 16% in 1931 and 25% in 1932, as noted in a blog post from businessman and Harvard Business School professor Bill George.

In addition to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, experts such as late economist Milton Friedman (via YouTube) have blamed other factors, such as the Federal Reserve's switch to a much tighter monetary policy in the early 1930s.

Herbert Hoover made things worse, but not in the way most think

Most sources say it in a number of different ways — Herbert Hoover was among the Great Depression's biggest heels, if not the biggest. He had become so unpopular toward the end of his term that when the 1932 elections rolled around, he carried only six states as Franklin D. Roosevelt beat him by a landslide (via History). But how true is it that Hoover was an advocate of laissez-faire economics — the belief that things will sort themselves out automatically in the event a capitalist economy fails?

As explained by EconLib, Hoover's Revenue Act of 1932 drastically raised income taxes across the board, with the lowest level increasing from a range of 1.5% to 5% to 4% to 8%. Those in the highest bracket, meanwhile, were taxed to the tune of 25% to 63% — sixty-three percent — after the act was passed. In an attempt to ensure that more Americans remained employed amid the Depression, he passed an executive order in September 1930 that almost blocked immigration. Then there's the fact he increased federal spending by close to 50% over his four-year term, as well as the aforementioned Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act.

As you can see above, those don't sound like the actions of a laissez-faire president. But it's not like his strategies to get America out of the economic rut it was in were any more effective than sitting back and watching.

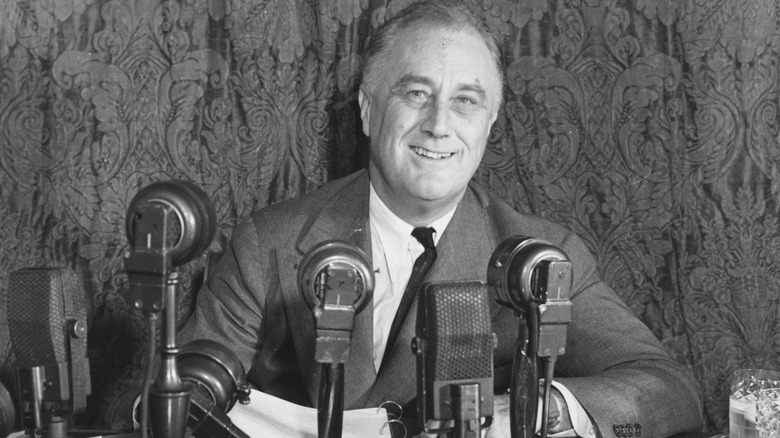

FDR's New Deal may have actually extended the Depression

The belief that President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies brought an end to the Great Depression is just another one of the many accepted — but not 100% accurate — narratives surrounding the protracted economic crisis. Granted, FDR's administration saw a lot of key economic metrics improve substantially, and he deserves credit for launching several productive banking, agricultural, and labor reforms as part of his platform. (And let's not forget Social Security!) However, saying that the New Deal was an instant gateway to recovery ignores the bigger picture.

According to The Washington Post, it took quite a while before there was a semblance to how things were before the Depression. There were even some counterproductive New Deal initiatives, such as the flagship National Industrial Recovery Act, which clearly favored large businesses and had too many vague regulations and caveats. The Cato Institute also notes that the act was one of several New Deal programs that led to hundreds of thousands of Blacks losing their jobs, further highlighting the racial inequality of the era. And to top it all off, there are some experts who believe that the New Deal actually extended the Great Depression; according to historian Stephen Davies, unemployment in 1937 was just as bad as it was in 1932, and the U.S. government had accumulated a staggering amount of debt.

World War II did not end the Great Depression either

Many history books will still tell you that the Great Depression ended when World War II started. Ultimately, that's another myopic way of looking at the situation. Writing for the Heritage Foundation, academic Stephen Moore pointed out that there was an increase in economic output and a major decrease in unemployment after the Pearl Harbor attack on December 7, 1941 — as of 1940, the jobless rate was still at 14.6 percent, underscoring once again why Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal was not a cure-all. But if you come to think of it, unemployment will certainly go down dramatically if you've got 12 million people enlisting in the military in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor.

"From 1942-45, America was not a free market economy; we were an all-out wartime economy –- with the normal laws of economics suspended," Moore continued, stressing that America wasn't "creating wealth" by building bombs and military vehicles during the Second World War.

Although economists warned that unemployment could potentially return to pre-war levels and then some once the war ended, that wasn't the case. Instead, government spending went down from 41% of the U.S. gross domestic product in 1945 to less than 15% in 1947, thanks in large part to President Harry Truman's initiatives. Conversely, personal consumption and private investment spending went up significantly in the immediate post-war years. According to Moore, it was a combination of these two trends that brought an end to the Great Depression some 15-plus years after it started — and not in the late '30s or early '40s, as most sources still insist.