The Untold Truth Of The Attack On Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor gained its name ("Wai Momi" in Hawaiian) through the pearl oysters in its waters, but it was whaling that first brought it and its island chain to the attention of the United States. Hawaii became a major port of call over the course of the 19th century. Even after America's whaling trade came into decline, the demand for sugar and fruit kept ships coming. And Hawaii's position in the Pacific made Washington consider it an appealing site to host a significant naval force.

Pearl Harbor was the only location in Hawaii deemed suitable to U.S. needs, and its exclusive use by America was guaranteed through a reciprocity treaty with Hawaii in the late 1800s. But its perceived value to American interests increased after the turn of the century when Hawaii was brought under direct U.S. control. The increasing aggression of Japan in the Pacific, particularly in regard to China, ratcheted up the tension between the two nations. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt placed the entirety of America's Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor as a deterrent while his administration pursued a diplomatic solution with the Japanese government.

But Japan had resolved to attack, and their preparations escaped American notice. That the December 7, 1941 strike on Pearl Harbor was a devastating blow to the U.S. Navy and the impetus for bringing the country into World War II is well-known. But many of the details from before, during, and after the attack are often passed over.

The Pacific fleet was at Pearl Harbor as a deterrent

If the attack on Pearl Harbor caught the Roosevelt administration by surprise, they had anticipated some manner of conflict with Japan for some time. The administration's Pacific policy stressed support and financial aid to China, which conflicted with Japanese designs on the country. After carving out Manchukuo from Manchuria to establish a puppet state, Japan engaged China directly in 1937, kicking off the Sino-Japanese War.

The U.S. answered this aggression by restricting exports to Japan and pulling out of a joint Treaty of Commerce and Navigation. By 1941, an embargo on any materials essential to the Japanese war effort was in place, and Japanese assets held in the U.S. were frozen. But Japan was not dissuaded from its imperial designs. After joining Germany and Italy in the Axis coalition and viewing Germany's attack against the Soviet Union as freeing Japan up in the east, the government of Hideki Tōjō only hardened its resolve.

Though he pursued a diplomatic solution to the rising tensions, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt felt the need to show some degree of force to try and deter Japan. "Roosevelt saw himself as a naval expert," author Steve Twomey told Military Times, and not without reason; he'd served in the Department of the Navy. It was Roosevelt who ordered America's Pacific fleet to Pearl Harbor as a show of strength.

The Japanese government was negotiating with the U.S. right up until the attack

By 1941, Japan had long been unhappy with the United States. The Roosevelt administration's support of China and its embargo against Japan was an irritant to the military forces in the government. Those forces were gaining influence by 1941. But that didn't stop Japan from engaging with the U.S. on a diplomatic solution.

Entering into an alliance with the Axis powers in Europe was part of that diplomacy; potential war with Germany would act as a deterrent against any attack on Japan. But both countries pursued peace talks. According to Robert A. Fearey, private secretary to the American ambassador to Japan, an Alaskan summit between President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoye was discussed, but it was tied up by attempts to settle part of the agenda beforehand, as well as Konoye's fear of leaks to extremists in his own country (via the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training). Konoye's replacement by Hideki Tōjō further damaged peace prospects.

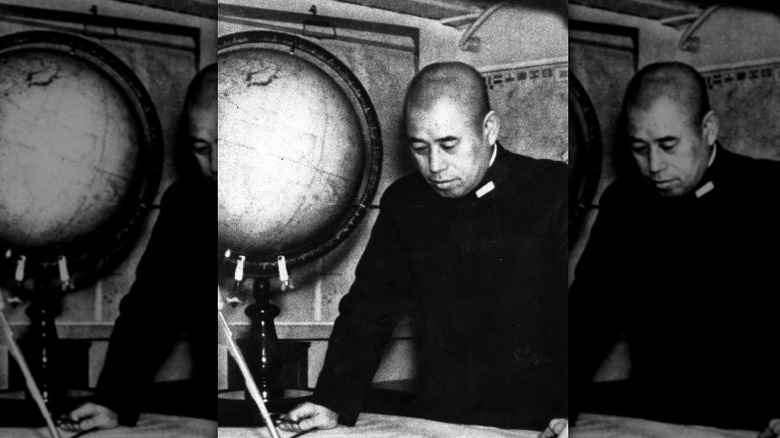

Negotiations were still ongoing when Tōjō's government decided to attack Pearl Harbor. The admiral responsible for planning the attack, Isoroku Yamamoto, had argued against joining the Axis and was well aware of Japan's odds in a war against the U.S. With the government deaf to his counsel, Yamamoto devised the Pearl Harbor attack as a rapid strike to cripple American forces. His plans were kept secret even from elements of the Japanese military.

America expected an attack, but not in Hawaii, or at that scale

Conspiracies, like old habits and cockroaches, are stubbornly resistant to death, and the claim that the Roosevelt administration knew that Japan was going to attack Pearl Harbor and let it happen to pull America into World War II persists to this day. There is no evidence to support that theory and plenty to refute it. Franklin Delano Roosevelt aimed to knock Japan out of its Pacific aggression through sanctions and diplomacy. Pearl Harbor was a complete surprise to him. But it was the location and nature of the attack that surprised him and his administration more than the fact Japan had struck at all.

The Roosevelt administration did not know Japan was planning to target any American territory in the Pacific. But with tensions between the two countries high and negotiations going poorly, it was considered possible, though unlikely, that some military action might happen. But if such an attack was to come, it was anticipated that the target would be naval bases in the Philippine islands. American intelligence judged a coordinated strike on the fleet at Pearl Harbor to be outside the Japanese military's scope and assumed that they wouldn't run the substantial risks such an attack demanded.

The congestion at Pearl Harbor limited the fleet's use

Had the U.S. Navy been alerted to the incoming attack on Pearl Harbor, it might have struggled to mount a solid defense on short notice. While stationing the entire Pacific fleet there demonstrated American naval might and put a fighting force in a key territory, it also put almost 100 ships in a small, shallow harbor with little maneuverability. "There was too little water for the number of ships," said Lt. Gen. Walter Short (via Military Times). Deploying the fleet would have taken hours. And there was insufficient ammunition at Pearl Harbor for the fleet.

Keeping the Pacific fleet bottled up where it would struggle to effectively respond to an attack wasn't universally popular in the Roosevelt administration. Admiral James O. Richardson, who had opposed creating a Hawaiian detachment in the first place, was forced to swallow a press release issued in his name to keep the fleet there. He argued that it should be based out of the West Coast of the continental United States, where resources would allow it to be properly prepared and deployed for war.

His pleas fell on deaf ears. The president himself wanted the fleet at Pearl Harbor, and it stayed there for over a year before the attack. During that time, it remained congested and unprepared; morale dropped; and the large sailor presence — undermanned though it was — became a source of tension for locals.

America fired the first shots

While there was no expectation that Japan would attack Pearl Harbor itself, Adm. Husband E. Kimmel and Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short were alerted in October and November that failed negotiations between Japan and America made military action possible. By December 7, war seemed likely, and fresh warnings were dispatched from Washington by telegram. But an error in communications kept the message from reaching Kimmel and Short until it was too late, and even had it been properly managed, it would have given them only around an hour's notice that something was amiss.

At the scene, there were early alerts that went unheeded. The USS Condor spotted a Japanese submarine four hours before the attack and passed on a warning. The USS Ward received it, and it came upon the sub two and a half hours later. It was the Ward, a repurposed destroyer from the first world war, that technically fired the first shots of the day. Per Special Operations Forces Report, commanding officer Lt William Outerbridge gave the order to fire, and the Ward sank the sub when it tried to penetrate Pearl Harbor itself (though the sinking wouldn't be confirmed until decades later).

Outerbridge sent an urgent warning that he'd engaged a hostile ship, which was dismissed at multiple points in the chain of command. A skeptical Kimmel wanted confirmation. But it was only minutes after he received Ward's warning that the Japanese attack began.

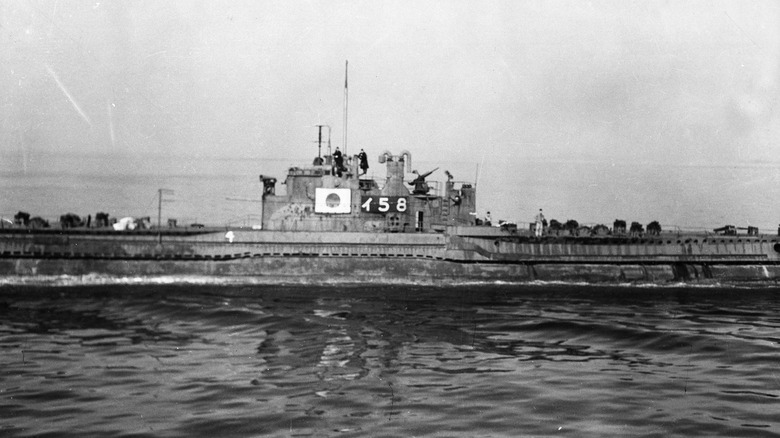

Japan's attempt to attack with submarines was a failure

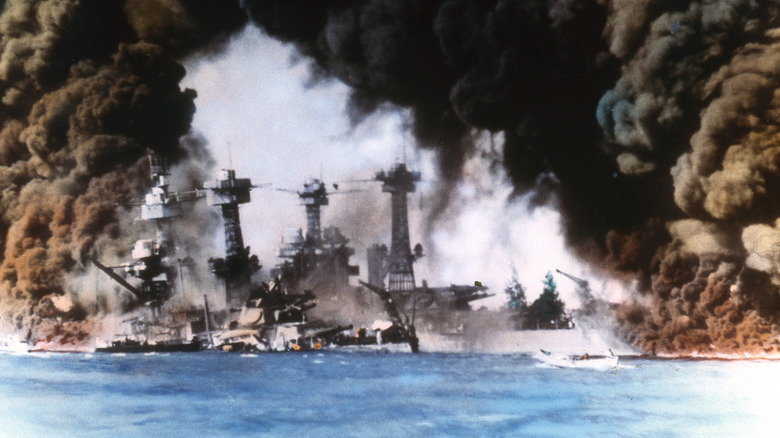

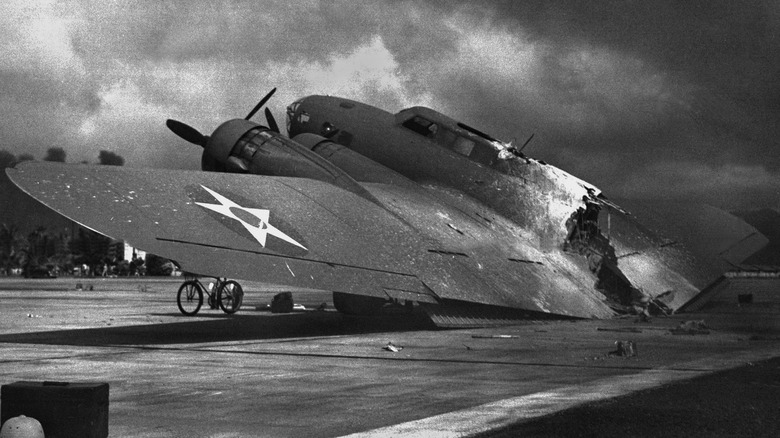

Shots of the destruction that rained down upon the Pearl Harbor Naval Air Station and Wheeler and Hickam fields on December 7, 1941, are some of the most haunting and enduring images from the second world war in the American psyche. Japan's dive bombers destroyed 180 American aircraft, destroyed two battleships, and damaged six more, severely damaging the rest of the fleet. Altogether, they claimed over 3,400 casualties. In the short term, the attack achieved Japan's aim of hobbling the U.S. Pacific naval force. But it wasn't a total victory, and elements of the attack were a debacle.

According to The National Interest, the aerial attack was meant to be complemented by a submarine strike within the harbor itself. Japan had developed a small fleet of subs, including five miniature submarines that were passed off as dummy ships made for target practice during development. Each required a two-man crew, ran on batteries, and could only reach a depth of 100 meters. Their theoretical endurance, rarely reached in practical use, was 12 hours.

The intent was to bring the mini-subs close to Pearl Harbor via full-sized subs before the bombers began their attack. After striking their targets, the mini-subs would retreat and be ferreted away. But none of the five had the chance. One was sunk by the USS Ward, another washed ashore, two disappeared, and the only one to reach the harbor was sunk.

Ships were sunk at berths; planes were destroyed on the airfields

With the clustered nature of the harbor and the surprise nature of the attack, the U.S. Pacific fleet was hit hard by the attack on Pearl Harbor. Planes and mini-submarines, launched from two directions, rained destruction on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941.

The first bombs struck at about 8 a.m. By 8:10 a.m., the battleship USS Arizona had exploded and was sinking almost instantaneously. Eyewitness to History quotes Marine Corporal E.C. Nightingale, who said, "Charred bodies were everywhere," as he struggled to abandon the ship. The 360 Japanese planes strafed, dropped bombs, and launched torpedoes in an attack lasting about two hours. The effect was devastating. All nine battleships had been either badly damaged or sunk (all but two would eventually be resurrected and restored to duty). Drydocks were damaged, as were airfields. Nearly 20 ships of various sizes were incapacitated or destroyed.

Why weren't U.S. aircraft carriers at Pearl Harbor?

As devastating as the attack on Pearl Harbor was to the U.S. Pacific fleet, it did not succeed in completely eliminating it. The fuel reserves and repair facilities escaped any damage, and many of the damaged ships were able to be salvaged. Most critically, however, the American aircraft carriers escaped the attack. They weren't even at Pearl Harbor at the time.

Aircraft carriers had become integral to naval warfare by the 1940s. The three carriers of the Pacific fleet were away on missions prior to December 7. The USS Enterprise was dispatched on November 28 to deliver fighter planes to Wake Island, the USS Lexington was dispatched on December 5 to deliver dive bombers to Midway, and the USS Saratoga was being refitted in San Diego. The Enterprise and Lexington were both en route back to Pearl Harbor, but both ships were delayed in their return by inclement weather.

Despite their significance to 20th-century combat, the Japanese did not consider the American carriers a primary target. They knew that the ships were away from Pearl Harbor but considered the attack too valuable an opportunity to strike at America's battleships. Once the attack began, the Lexington was ordered to search for the Japanese fleet but was unsuccessful. The Enterprise, having dispatched bombers ahead of its return to the harbor, thereby made a contribution to the defense, but it was also unable to find the enemy fleet.

There was an attempt to formally declare war before the attack

Japan determined to attack the United States as early as November 1941, though it continued negotiations throughout the month. The plans for the strike at Pearl Harbor were kept close to the chest; very few in the chain of command were let in on Isoroku Yamamoto's work. When the fateful day came, Japan's ambassadors asked to see the secretary of state, which was taken as a sign of impending war. But the attack came without any formal declaration beforehand, and in fact, the ambassadors' message was delayed until after the attack had already begun.

According to former ambassador Takeo Iguchi (via the University of Virginia School of Law), protocol demanded that Japan issue a clear ultimatum prior to any military action, which the request to the secretary of state was not. But this wasn't the first instinct of the government. Based on official documents discovered in 1999, Iguchi concluded that Japan's foreign ministry attempted to abide by international law and provide a formal ultimatum before the attack. But elements in the Japanese military, which considered America's ignorance key to the success of the operation, prevented any notice that would have let the enemy prepare.

Over 2,400 military and civilians died in the attack

American forces tried to fight back. According to Walter Lord's Day of Infamy, 11 Japanese planes were shot down by Army pilots — seven of them by just two pilots, Lts. Kenneth Taylor and George Welch. The attack was effective, and the Japanese had missed crucial targets: ammunition depots, repair facilities, fuel storage, and the Navy's aircraft carrier and submarine fleets. These all proved vital in striking back against the Japanese Empire, particularly at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, when U.S. carrier forces effectively destroyed the Japanese fleet.

Japan declared war on the U.S. an hour into the attack. On December 8, President Franklin Roosevelt gave his "Day of Infamy" speech and asked Congress to declare war against Japan. Per the Library of Congress, he said, "(W)e will not only defend ourselves to the uttermost but will make very certain that this form of treachery shall never endanger us again." Within days, Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S., and the U.S. reciprocated. The world was at war.

Friendly fire took the most civilian lives

The human toll of Pearl Harbor was immense. Over 3,400 Americans suffered some form of damage, with 2,335 servicemen killed in the attack. Japan suffered fewer than 100 losses. There were also 68 civilian casualties on the island of Oahu. And most of those citizens didn't fall to enemy fire. Defensive fire from the U.S. Coast Guard didn't always reach their targets. Shells intended for Japanese bombers fell elsewhere on the island, even in the city of Honolulu. Most civilians who died that day, including 11 children, were victims of these rounds of friendly fire.

Other civilians had harrowing experiences of a different nature. Writing for Smithsonian, author Marc Wortman recounted some of the experiences of civilian survivors of the attack. The Coe family lived in Nob Hill when the Japanese bombers came. Forced into refuge inside a bunker, the Coes bore witness to the stream of injured and dying seamen retreating inside after being caught in the attack. Fears of a full-scale invasion were great enough that Mrs. Coe, having heard rumors of Japanese war crimes, asked a soldier to kill her and her two children before letting them fall into enemy hands, should it come to that.

There was a second attack attempted on Pearl Harbor

Japan wasn't finished with the U.S. Pacific fleet after December 7. Japanese submarines remained in the area through late January, occasionally shelling targets on land and sea. A more extensive plan meant for March 4, 1942, known as Operation K, was devised to investigate and frustrate America's recovery from Pearl Harbor. The plan was to send out five flying boats from the Marshall Islands to the French Frigate Shoals, and then to Oahu. They would survey the port, each one carrying four bombs designed to panic the locals and target a repair facility.

Unfortunately for Japan, one thing after another went wrong in Operation K. Only two of the five planes intended were on hand to be used. The submarine responsible for relaying weather reports was lost before the mission began, leaving the flying boats unprepared for the thick cloud cover over Hawaii. The clouds also impeded the American planes sent to intercept them, but if that protected the bombers from enemy fire, it also obscured their target. The closest a bomb came to doing any damage was destroying the windows of Roosevelt High School in Honolulu when it landed 900 feet away.

The failed second strike clued in American forces to what the Japanese had in mind. An attempted repeat in May saw the U.S. Navy well-prepared to intercept any assault, leaving Operation K dead in the water.