The Dramatic Way The Printing Press Changed History Forever

Forget for a moment all your Kindles and their digital libraries, your instantly obtained Adobe Acrobat documents, and your endless ream of text after scrolling text on website after website. Forget public libraries, every student textbook, every flyer, magazine, want ad, and lost kitten posters on telephone poles. Forget even the simple pleasure of striding into a brick-and-mortar bookstore and smelling the paperbacks. Because a mere 600 years or so ago, what seems so commonplace nowadays — books — might have gone completely unseen for a person's entire life.

Written language took the first step of off-loading the mind and limitations of human memory onto a secure, immutable source (barring fires). The very perception of past and future changed from immanent and transmissible only from person to person, voice to voice, into tales that lived on pages, not on grasslands wandered by people. Knowledge could be compounded, and the conscious mind redirected onto more than remembering facts or recalling oral tales. It could roam over new possibilities.

Conjoin this with post-Medieval European economic prosperity and a widening middle class capable of spending time on even more specialized tasks than our forbears, and the stage is set for the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and now the Information-Age-turned-Experience-Age. This entire cumulative revolution — every single datum and iota and phoneme of poet, academic, or researcher, as overviewed by the Great Courses — hinged almost entirely on the development of the printing press in the 1430s.

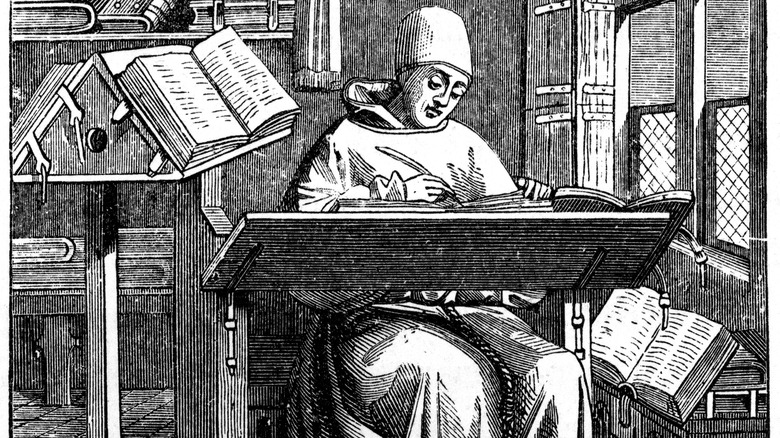

Monks in scriptoriums were the original 'printing press'

Before the printing press, the creation of even a single book was an incredibly painstaking, laborious process. Until about the 12th century in the West, from the fall of the Western Roman Empire about 476 C.E. (per History), sole responsibility for creating books fell to monks. And by "creating" we mean copying existent pieces of literature, not writing anything new. The most fortunate of monks worked at places like St. Gallen Monastery in modern-day Switzerland, in a bright, airy room with a central desk for a supervisor and smaller desks arrayed around the periphery, as the blog On History helps us visualize. Others worked in less ideal environments, without luxuries like tilted desks, oftentimes in solitude for years, hearing little but the scratch of a quill.

And let's be clear: these monks didn't merely jot things down on post-it notes. We're talking every piece of the book-creation process, from each letter to binding, inlays, decorations, pictures, and so forth. Mind-boggling illuminated manuscripts, like those on World History, represent countless hours of obsessive labor for a single book, using luminous ink made from actual silver and gold. This is a far, far cry from a $6.99 mass-produced paperback at Barnes and Noble — although the eventual, useless cheapness of literature was a direct result of the printing press, as well. Even only bookbinding itself, as a telling video on Nerdforge shows, required intensive skill, talent, and time.

Gutenberg was just low on cash

Johannes Gutenberg didn't intend to change the world forever when he invented the printing press; he was just low on cash. As PS Print cites, woodblock prints had been in use since the 1300s, whereby ink was pressed on a static piece of carved wood and pressed onto paper. Presto: instant page.

It bears telling that such devices had been in use in China since about 600 C.E., as Live Science reminds us. The complexities of the Chinese written language, though — which began as "pictographic logograms" (pictures of things) and evolved into complex images of full semantic meaning — meant that swapping pieces of text via moveable type was absurdly cumbersome. The Roman alphabet, a tiny assemblage of recombinant phonetic symbols (26 letters in English, for example), was the perfect vehicle for the development of a mechanical printing press with movable metal letters able to be shifted into any combination. As World History tells us, it took 20 years for Gutenberg's invention to become profitable. He passed away in 1468, in debt, and before he could witness the impact of his device.

The impact of the printing press was soon to come, though. By 1519, per Washington Post, a relatively unknown monk named Martin Luther had gone from tacking his 95 Theses to the door of a local German church to producing 300 editions of his writings and become the most published author in Europe. No printing press, no Protestant Reformation.

The democratization of the written, vernacular word

It's ironic that Gutenberg's printing press helped facilitate the Protestant Reformation, because originally he saw the Catholic Church as his best customer, per the Great Courses. Uniform, papally sanctioned Bibles, the strengthening of traditional Christendom and its squashing of political opponents, and a resultant flow of cash directly to him: this was Gutenberg's vision.

Instead, the democratization of information via the written word had the opposite effect, much like what many envisioned of the early days of the internet. Knowledge spread more freely and cheaply. The authority of the state and the papacy was weakened. The printing press fueled the intellectual movement of the Renaissance, which started in late 14th-century Italy. It breathed life back into the mind of skepticism that yielded the Enlightenment, modern humanism, and its necessary refutation of sacred cows that restrained scientific investigation. And now? You've got your smartphone to learn about this kind of stuff.

Literacy is a necessary point to make here, as well. The printing press wrested authority away from a Latin-wielding priesthood and gave it to a vernacular-speaking public. Writing could not only be widespread but read by the literate in their own languages. By 1605, the world's first modern novel, "Don Quixote," written in Spanish, kickstarted the development of the novel. Tales could be told of common folk, not merely classics about gods and redoubtable heroes. Alternative takes on ethics and philosophy eventually spread like wildfire, as well as all the critiques and discussions therein.